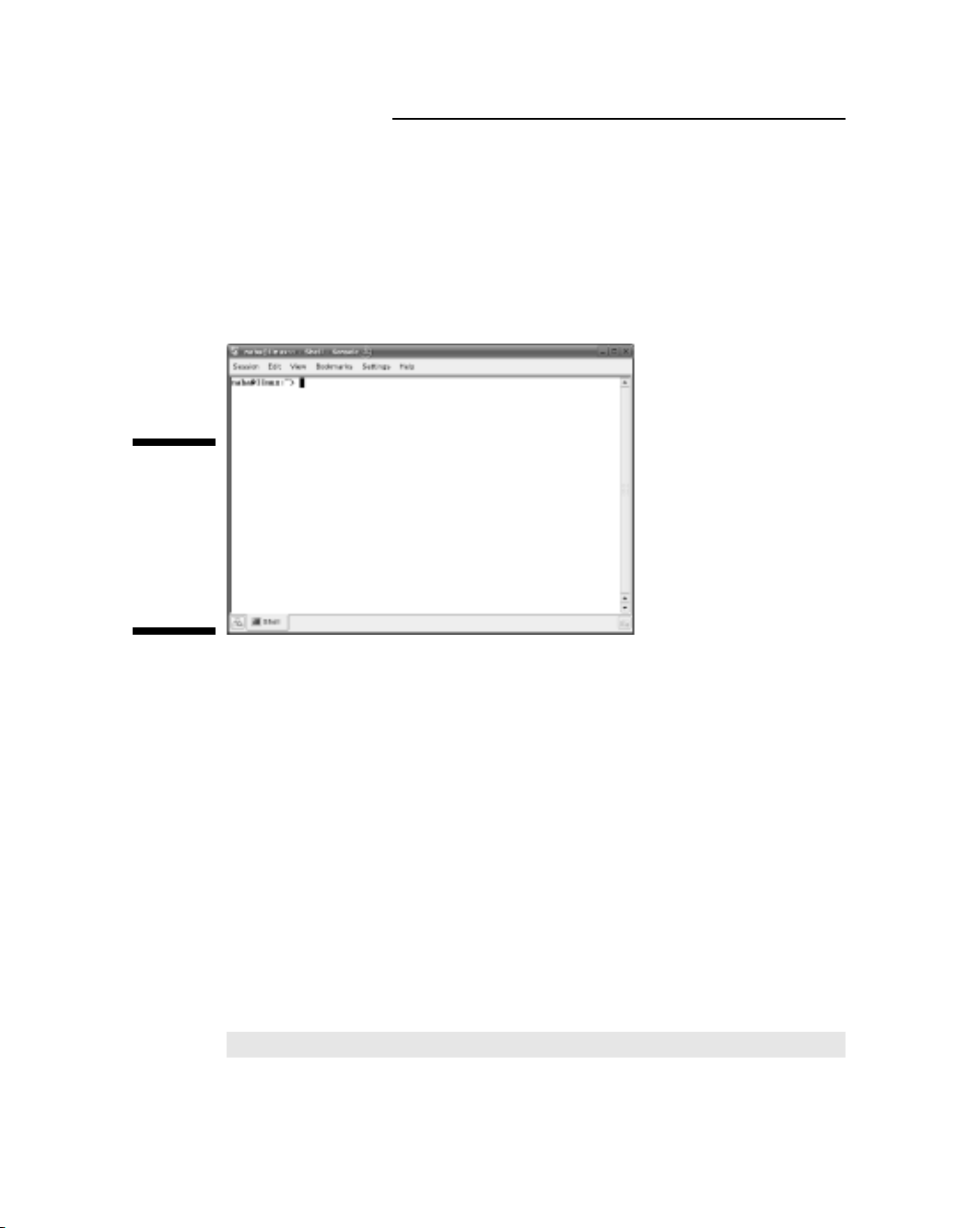

the one shown in Figure 3-7. That’s a terminal window, and it works just like

an old-fashioned terminal. A shell program is running and ready to accept

any text that you type. You type text, press Enter, and something happens

(depending on what you typed).

In GNOME, choose Applications➪System➪Terminal➪Gnome Terminal. That

should then open up a terminal window.

The prompt that you see depends on the shell that runs in that terminal

window. The default Linux shell is called bash.

Bash understands a whole host of standard Linux commands, which you can

use to look at files, go from one directory to another, see what programs are

running (and who else is logged in), and a whole lot more.

In addition to the Linux commands, bash can run any program stored in an

executable file. Bash can also execute shell scripts — text files that contain

Linux commands.

Understanding shell commands

Because a shell interprets what you type, knowing how the shell figures out the

text that you enter is important. All shell commands have this general format:

command option1 option2 ... optionN

Such a single line of commands is commonly called a command line. On a com-

mand line, you enter a command followed by one or more optional parameters

Figure 3-7:

You can

type Linux

commands

at the shell

prompt in a

terminal

window.

48 Part I: Getting to Know SUSE

(or arguments). Such command line options (or command line arguments)

help you specify what you want the command to do.

One basic rule is that you have to use a space or a tab to separate the com-

mand from the options. You also must separate options with a space or a tab.

If you want to use an option that contains embedded spaces, you have to put

that option inside quotation marks. For example, to search for two words of

text in the password file, I enter the following grep command (grep is one of

those cryptic commands used to search for text in files):

grep “SSH daemon” /etc/passwd

When grep prints the line with those words, it looks like this:

sshd:x:71:65:SSH daemon:/var/lib/sshd:/bin/false

If you created a user account in your name, go ahead and type the grep com-

mand with your name as an argument, but remember to enclose the name in

quotes. For example, here is how I search for my name in the /etc/passwd

file:

grep “Naba Barkakati” /etc/passwd

Trying a few Linux commands

While you have the terminal window open, try a few Linux commands just for

fun. I guide you through some random examples to give you a feel for what

you can do at the shell prompt.

To see how long the Linux PC has been up since you last powered it up, type

the following (Note: I show the typed command in bold, followed by the

output from that command.):

uptime

3:52am up 29 days 55:53, 5 users, load average: 0.04,

0.32, 0.38

The part up 29 days, 55:53 tells you that this particular PC has been up

for nearly a month. Hmmm . . . can Windows do that?

To see what version of Linux kernel your system is running, use the uname

command like this:

uname -srv

49

Chapter 3: Starting SUSE for the First Time

This runs the uname command with three options -s, -r, and -v (these can

be combined as -srv, as this example shows). The -s option causes uname

to print the name of the kernel, -r prints the kernel release number, and -v

prints the kernel version number. The command generates the following

output on one of my Linux systems:

Linux 2.6.13-8-default #1 Tue Sep 6 12:59:22 UTC 2005

In this case, the system is running Linux kernel version 2.6.13.

To read a file, use the more command. Here’s an example that displays the

contents of the /etc/passwd file:

more /etc/passwd

root:x:0:0:root:/root:/bin/bash

bin:x:1:1:bin:/bin:/bin/bash

daemon:x:2:2:Daemon:/sbin:/bin/bash

lp:x:4:7:Printing daemon:/var/spool/lpd:/bin/bash

... lines deleted ...

To see a list of all the programs currently running on the system, use the ps

command, like this:

ps ax

The ps command takes many options, and you can provide these options

without the usual dash (-) prefix. This example uses the aand xoptions —

the aoption lists all processes that you are running, and the xoption dis-

plays all the rest of the processes. The net result is that ps ax prints a list of

all processes running on the system, as shown in the following sample

output:

PID TTY STAT TIME COMMAND

1 ? S 0:01 init [5]

2 ? SN 0:10 [ksoftirqd/0]

3 ? S< 0:00 [events/0]

4 ? S< 0:00 [khelper]

9 ? S< 0:00 [kthread]

19 ? S< 0:00 [kacpid]

75 ? S< 0:02 [kblockd/0]

... lines deleted ...

Amazing how many programs can run on a system even when only you are

logged in as a user, isn’t it?

As you can guess, you can do everything from a shell prompt, but it does take

some getting used to.

50 Part I: Getting to Know SUSE

Shutting Down

When you’re ready to shut down Linux, you must do so in an orderly manner.

Even if you’re the sole user of a SUSE Linux PC, several other programs are

usually running in the background. Also, operating systems such as Linux try

to optimize the way that they write data to the hard drive. Because hard

drive access is relatively slow (compared with the time needed to access

memory locations), data generally is held in memory and written to the hard

drive in large chunks. Therefore, if you simply turn off the power, you run the

risk that some files aren’t updated properly.

Any user (you don’t even have to be logged in) can shut down the system

from the desktop or from the graphical login screen. In KDE, choose Main

Menu➪Log Out. In GNOME, choose Desktop➪Log Out. A dialog box appears

(Figure 3-8 shows the example from the KDE desktop), providing the options

for restarting or turning off the system, or simply logging out. To shut down

the system, simply select Turn Off Computer (or Shut Down in GNOME), and

click OK. The system then shuts down in an orderly manner.

Figure 3-8:

Shutting

down your

SUSE Linux

system from

the KDE

desktop.

51

Chapter 3: Starting SUSE for the First Time

If you are at the graphical login screen, you can shut down the system by

selecting the shutdown option from the menus available at the login screen.

As the system shuts down, you see text messages about processes being shut

down. You may be surprised at how many processes exist, even when no one

is explicitly running any programs on the system. If your system does not

automatically power off on shutdown, you can manually turn off the power.

Note that shutting down or rebooting the system may not require root

access or even the need to log in to the system. This is why it’s important to

make sure that physical access to the console is protected adequately so that

anyone who wants to cannot simply walk up to the console and shut down

your system.

52 Part I: Getting to Know SUSE

![Bài giảng Phần mềm mã nguồn mở [mới nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20250526/vihizuzen/135x160/6381748258082.jpg)

![Tài liệu giảng dạy Hệ điều hành [mới nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20250516/phongtrongkim0906/135x160/866_tai-lieu-giang-day-he-dieu-hanh.jpg)

![Bài giảng Hệ điều hành: Trường Đại học Công nghệ Thông tin (UIT) [Mới nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20250515/hoatrongguong03/135x160/6631747304598.jpg)

![Bài giảng Hệ điều hành Lê Thị Nguyên An: Tổng hợp kiến thức [mới nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20250506/vinarutobi/135x160/8021746530027.jpg)

![Đề thi Excel: Tổng hợp [Năm] mới nhất, có đáp án, chuẩn nhất](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20251103/21139086@st.hcmuaf.edu.vn/135x160/61461762222060.jpg)

![Bài tập Tin học đại cương [kèm lời giải/ đáp án/ mới nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20251018/pobbniichan@gmail.com/135x160/16651760753844.jpg)

![Bài giảng Nhập môn Tin học và kỹ năng số [Mới nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20251003/thuhangvictory/135x160/33061759734261.jpg)

![Tài liệu ôn tập Lý thuyết và Thực hành môn Tin học [mới nhất/chuẩn nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20251001/kimphuong1001/135x160/49521759302088.jpg)

![Trắc nghiệm Tin học cơ sở: Tổng hợp bài tập và đáp án [mới nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20250919/kimphuong1001/135x160/59911758271235.jpg)

![Giáo trình Lý thuyết PowerPoint: Trung tâm Tin học MS [Chuẩn Nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20250911/hohoainhan_85/135x160/42601757648546.jpg)