DtpB (YhiP) and DtpA (TppB, YdgR) are prototypical

proton-dependent peptide transporters of Escherichia coli

Daniel Harder

1

,Ju

¨rgen Stolz

1

, Fabio Casagrande

2

, Petr Obrdlik

3

, Dietmar Weitz

1

,

Dimitrios Fotiadis

2,*

and Hannelore Daniel

1

1 Molecular Nutrition Unit, Technical University of Munich, Freising, Germany

2 M.E. Mu

¨ller Institute for Structural Biology, Biozentrum, University of Basel, Switzerland

3 IonGate Biosciences GmbH, Frankfurt, Germany

Uptake of peptides into Escherichia coli cells is

thought to be mediated by three different transport

systems represented by the dipeptide permease Dpp,

the tripeptide permease TppB, and the oligopeptide

permease Opp [1–3]. Despite the fact that these pro-

teins seem to discriminate according to the backbone

length of peptide substrates, they do show some over-

lapping specificity. Although their prime physiological

role is in the uptake of peptide-bound amino acids as

an economic process to provide energy substrates and

building blocks for cellular metabolism, peptide uptake

seems also to be involved in signaling processes and

metabolic adaptation [4]. Whereas Opp and Dpp rep-

resent ATP-binding cassette transporters with periplas-

matic binding proteins [5–7], TppB belongs to the

family of proton-dependent peptide symporters that

utilize the proton gradient as driving force and lack

cognate binding proteins [8]. After identification of the

Keywords

E. coli; peptide; PTR; TppB; transport

Correspondence

H. Daniel, Molecular Nutrition Unit,

Technical University of Munich, Am Forum

5, D-85350 Freising, Germany

Fax: +49 8161713999

Tel: +49 8161713400

E-mail: daniel@wzw.tum.de

*Present address

Institute of Biochemistry and Molecular

Medicine, University of Berne, Switzerland

(Received 18 February 2008, revised 20

March 2008, accepted 23 April 2008)

doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06477.x

The genome of Escherichia coli contains four genes assigned to the peptide

transporter (PTR) family. Of these, only tppB (ydgR) has been character-

ized, and named tripeptide permease, whereas protein functions encoded by

the yhiP,ybgH and yjdL genes have remained unknown. Here we describe

the overexpression of yhiP as a His-tagged fusion protein in E. coli and

show saturable transport of glycyl-sarcosine (Gly-Sar) with an apparent

affinity constant of 6.5 mm. Overexpression of the gene also increased the

susceptibility of cells to the toxic dipeptide alafosfalin. Transport was

strongly decreased in the presence of a protonophore but unaffected by

sodium depletion, suggesting H

+

-dependence. This was confirmed by puri-

fication of YhiP and TppB by nickel affinity chromatography and reconsti-

tution into liposomes. Both transporters showed Gly-Sar influx in the

presence of an artificial proton gradient and generated transport currents

on a chip-based sensor. Competition experiments established that YhiP

transported dipeptides and tripeptides. Western blot analysis revealed an

apparent mass of YhiP of 40 kDa. Taken together, these findings show

that yhiP encodes a protein that mediates proton-dependent electrogenic

transport of dipeptides and tripeptides with similarities to mammalian

PEPT1. On the basis of our results, we propose to rename YhiP as DtpB

(dipeptide and tripeptide permease B), by analogy with the nomenclature

in other bacteria. We also propose to rename TppB as DtpA, to better

describe its function as the first protein of the PTR family characterized in

E. coli.

Abbreviations

AMCA, b-Ala-Lys-N

e

-7-amino-4-methylcoumarin-3-acetic acid; CCCP, carbonyl cyanide m-chlorophenylhydrazone; DDM, n-dodecyl-b-D-

maltoside; Gly-Sar, glycyl-sarcosine; IPTG, isopropyl-thio-b-D-galactoside; TMPD, N,N,N¢,N¢-tetramethyl-p-phenylenediamine.

3290 FEBS Journal 275 (2008) 3290–3298 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS

corresponding gene ydgR [8,9], it was genetically classi-

fied as a member of the peptide transport (PTR) fam-

ily (also called proton-dependent oligopeptide

transporter or POT family). These transporters are

found essentially in all living organisms from bacteria

to humans, with examples such as DtpT from Lacto-

coccus lactis, Ptr2 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, and

the mammalian transporters PEPT1 and PEPT2

[10,11]. The first attempts to functionally characterize

TppB in Salmonella typhimurium [12,13] and in E. coli,

employing deletion mutants [14,15], provided some

information on substrate preferences, and demon-

strated upregulation of transport upon anaerobiosis

and by Leu [13,16]. Although TppB, like Dpp, was

shown to transport dipeptides and tripeptides, it

seemed to prefer tripeptides, and in particular those of

a hydrophobic nature. The transport mode of TppB,

however, was poorly characterized. We recently cloned

ydgR encoding TppB, and overexpressed the gene for

a detailed functional analysis of the encoded trans-

porter and its initial structural characterization. We

observed a striking functional similarity between YdgR

and the mammalian PEPT1 protein [17], and therefore

the bacterial PTR transporters may serve as models

for elucidating the structure. They are easily purified in

large quantities for crystallization approaches to derive

appropriate structural models. These might then be

applied also to the human proteins, which are also of

great interest for pharmacalogical applications, e.g.

delivery of peptidomimetic drugs in the intestine.

Three of the four E. coli members of the PTR family

(yhiP,ybgH and yjdL) have not been studied yet. We

here report the cloning of yhiP and the purification

and characterization of the corresponding transport

protein. Furthermore, we compared the functional fea-

tures of YhiP with that of TppB to improve our

understanding of peptide transport processes in bacte-

ria. We established that tppB and yhiP code for proto-

typical H

+

-coupled symporter proteins that are

specific for dipeptides and tripeptides. By analogy to

similar transporters in other prokaryotes, we propose

to name them Dtp (dipeptide and tripeptide permeas-

es), with the first one identified being DtpA (former

TppB, YdgR), and DtpB (YhiP) being described here

as the second member of the PTR family in E. coli.

Results

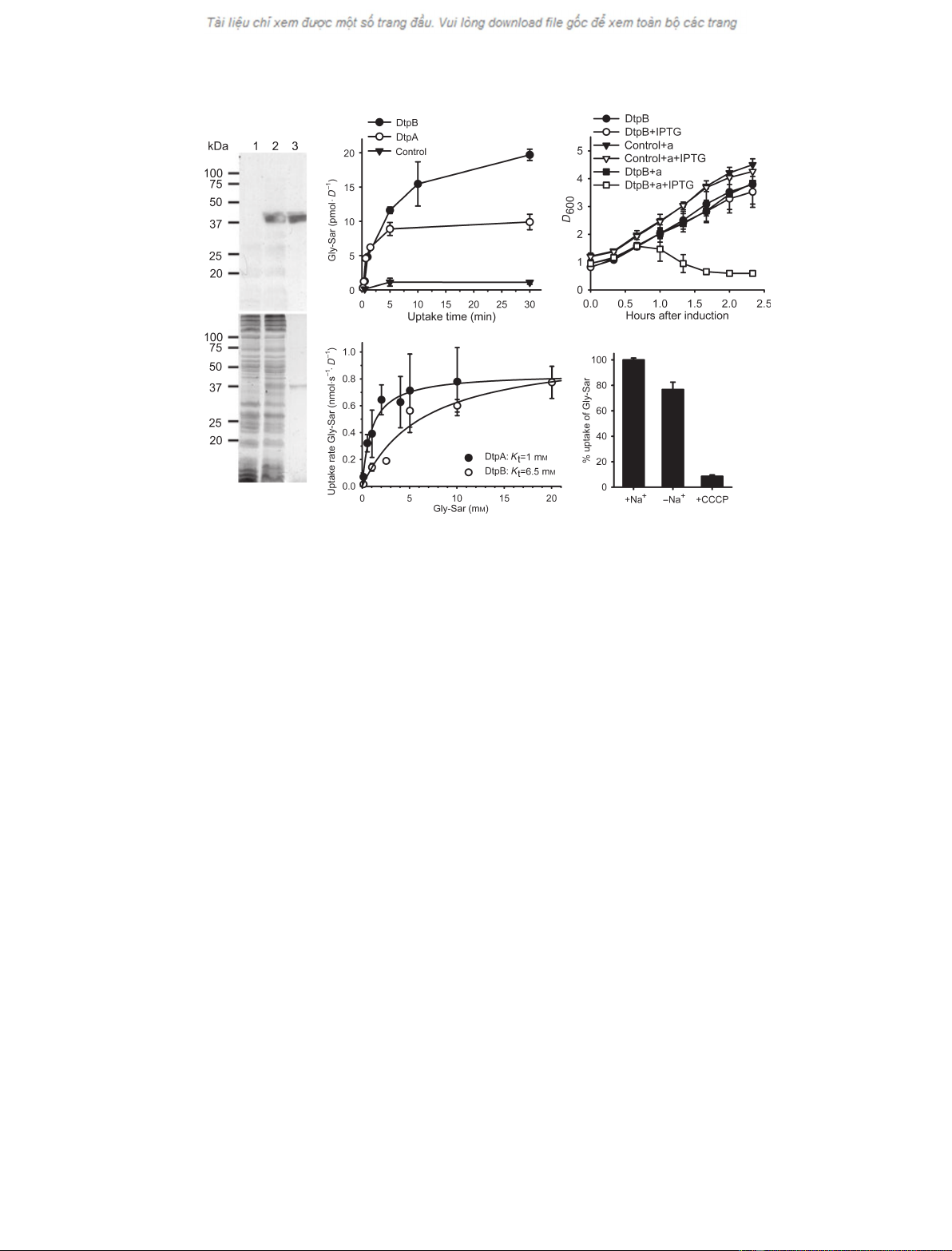

Functional overexpression of dtpB in E. coli

Using a similar approach as previously reported for

dtpA (tppB,ydgR) [17], we amplified the dtpB (yhiP)

gene of E. coli from genomic DNA by PCR using

gene-specific primers. The gene was cloned into the

pET-21 vector fused with a C-terminal hexahistidine-

tag. The expression level of dtpB in E. coli

BL21(DE3)pLysS was assayed by western blot analysis

with an antibody against the hexahistidine-tag. This

antibody detected a protein with an apparent molecu-

lar mass of about 40 kDa in membrane preparations

of dtpB-overexpressing cells (Fig. 1A, upper panel,

lane 2). As no signal was obtained with isopropyl-thio-

b-d-galactoside (IPTG)-induced cells carrying an

empty vector (Fig. 1A, lane 1), this band clearly repre-

sented DtpB, which was also confirmed by the signal

of the nickel affinity chromatography-purified DtpB

(Fig. 1A, lane 3). The expected molecular mass based

on the amino acid sequence of DtpB is 54.6 kDa. A

similar increased mobility in SDS ⁄PAGE was observed

for DtpA, where we provided evidence that the protein

was complete by probing it with a second antibody

that recognized an added N-terminal tag [17].

To assess the function of DtpB, we determined the

uptake of radiolabeled [

14

C]glycyl-sarcosine (Gly-Sar),

a commonly used reporter substrate for mammalian

peptide transporters (Fig. 1B). Cells overexpressing

dtpB showed a higher uptake of Gly-Sar than control

cells. This was also the case for DtpA, indicating that

both proteins mediate efficient Gly-Sar uptake. As a

second approach to assess the functionality of the

transport protein, we performed growth experiments

(Fig. 1C) with the toxic phosphonopeptide alafosfalin,

a known substrate of DtpA. E. coli cells carrying the

expression vector for dtpB or the empty vector were

pregrown in the presence of a nonlethal concentration

of alafosfalin (500 lgÆmL

)1

, 2.55 mm), and gene

expression was induced by addition of IPTG. Cells

overexpressing dtpB showed strong growth inhibition

1 h after induction. The fact that cells carrying the

empty vector, noninduced cells or induced cells with-

out alafosfalin showed no growth inhibition demon-

strated the specificity of DtpB-mediated uptake of

alafosfalin. In similar experiments with DtpA, lower

alafosfalin concentrations (200 lgÆmL

)1

, 1.02 mm)

were needed for growth inhibition [17]. To directly

compare the substrate affinities of DtpB and DtpA, we

determined the uptake rates in cells overexpressing the

corresponding genes as a function of Gly-Sar concen-

tration (Fig. 1D). Transport was found to be saturable

with an apparent K

t

of 6.5 mmfor DtpB and 1 mm

for DtpA. We next investigated whether transport

requires Na

+

or H

+

(Fig. 1E). When we replaced

Na

+

in the buffer by choline, this had only a minor

effect on uptake of Gly-Sar, whereas the presence of

the proton ionophore carbonyl cyanide m-chloro-

phenylhydrazone (CCCP) caused complete inhibition

D. Harder et al. Proton-dependent peptide transporters of E. coli

FEBS Journal 275 (2008) 3290–3298 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS 3291

of transport. This suggests that uptake via DtpB

depends on the proton-motive force, and that DtpB

may function as a proton–peptide cotransporter.

Substrate specificity of DtpB

To assess the substrate specificity of DtpB (and DtpA,

for comparison), we performed competition experi-

ments with 1 mmGly-Sar as a substrate and 10 mm

competitors in E. coli cells overexpressing either dtpB

or dtpA. The uptake rates in the presence of the com-

petitor are presented in Table 1. The substrate specific-

ity data presented here for DtpA essentially match

those determined with b-Ala-Lys[b-Ala-Lys-N

e

-7-

amino-4-methylcoumarin-3-acetic acid(AMCA)], a fluo-

rescent dipeptide analog used as a substrate in our

previous study [17]. Similar to DtpA, neither the

amino acid Ala nor the tetrapeptide Ala-Ala-Ala-Ala

caused significant inhibition of DtpB-mediated trans-

port. In the case of DtpB, essentially all tested compet-

itors reduced transport to a lower extent than with

DtpA, which reflects its generally lower affinity.

Despite this, there were differences between DtpB and

DtpA when inhibitory effects of individual peptides

were compared. In the case of DtpB, peptides contain-

ing d-stereoisomers of l-Ala essentially failed to inhibit

uptake, whereas for DtpA, strong inhibition was

observed with d-Ala when it was placed in an N-termi-

nal position. Virtually no competition was seen in both

transporters with peptides containing only d-Ala. We

also assessed the effects of charged amino acid residues

and their spatial position on the uptake of Gly-Sar. In

the case of DtpA, a positively charged amino acid at

the N-terminus caused stronger inhibition than one

at the C-terminus. A negatively charged residue was

clearly preferred at the C-terminus. This was also

observed with DtpB, but here inhibition was higher with

Gly-Asp than in the case of DtpA. Selected b-lactam

A B C

D E

Fig. 1. Overexpression of dtpB in E. coli. (A) Anti-His-tag western blot (upper panel) and Coomassie-stained (lower panel) SDS gel (12.5%

acrylamide) of E. coli membranes of control cells (lane 1, 50 lg of total protein) or membranes containing overproduced DtpB (lane 2, 50 lg

of total protein) or purified DtpB (0.5 lg upper panel, 1.5 lg lower panel). (B) Uptake of [

14

C]Gly-Sar (1 mM)byE. coli cells carrying the

expression plasmid for dtpA or dtpB or the empty vector 3 h after induction with IPTG. Overexpression of either gene causes increased

Gly-Sar transport relative to the control. n= 2, ± SD. (C) Growth inhibition by alafosfalin. Induced (+ IPTG) or not induced cells, carrying

either the expression plasmid for dtpB or an empty plasmid, were grown in the presence of 500 lgÆmL

)1

(2.55 mM) alafosfalin (+ a) or with-

out alafosfalin. n= 2, ± SD. (D) Saturation kinetics for DtpA and DtpB. Uptake assays were performed with E. coli cells overexpressing dtpA

or dtpB, in the presence of various concentrations of Gly-Sar. The uptake velocities were determined using four time points (10, 20, 40 and

60 s). K

t

values were determined by nonlinear regression analysis of the presented data. n‡2, ± SD. (E) Sodium and proton dependence of

Gly-Sar uptake. For E. coli cells overexpressing dtpB, Gly-Sar (50 lM) uptake rates were determined from a 10 min time course. The rates

were determined in buffers containing 150 mMNaCl (+ Na

+

), or cholinechloride (150 mM) or in the presence of NaCl and the protonophore

CCCP (10 lM); 100% corresponds to 3.3 pmolÆs

)1

ÆD

)1

.n= 2, ± SD.

Proton-dependent peptide transporters of E. coli D. Harder et al.

3292 FEBS Journal 275 (2008) 3290–3298 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS

antibiotics (peptidomimetics) are known substrates of

mammalian peptide transporters. DtpA showed efficient

inhibition when an excess of cefadroxil, cefalexin or

cephradine was added, whereas only cephradine and

cefalexin significantly reduced Gly-Sar uptake via DtpB.

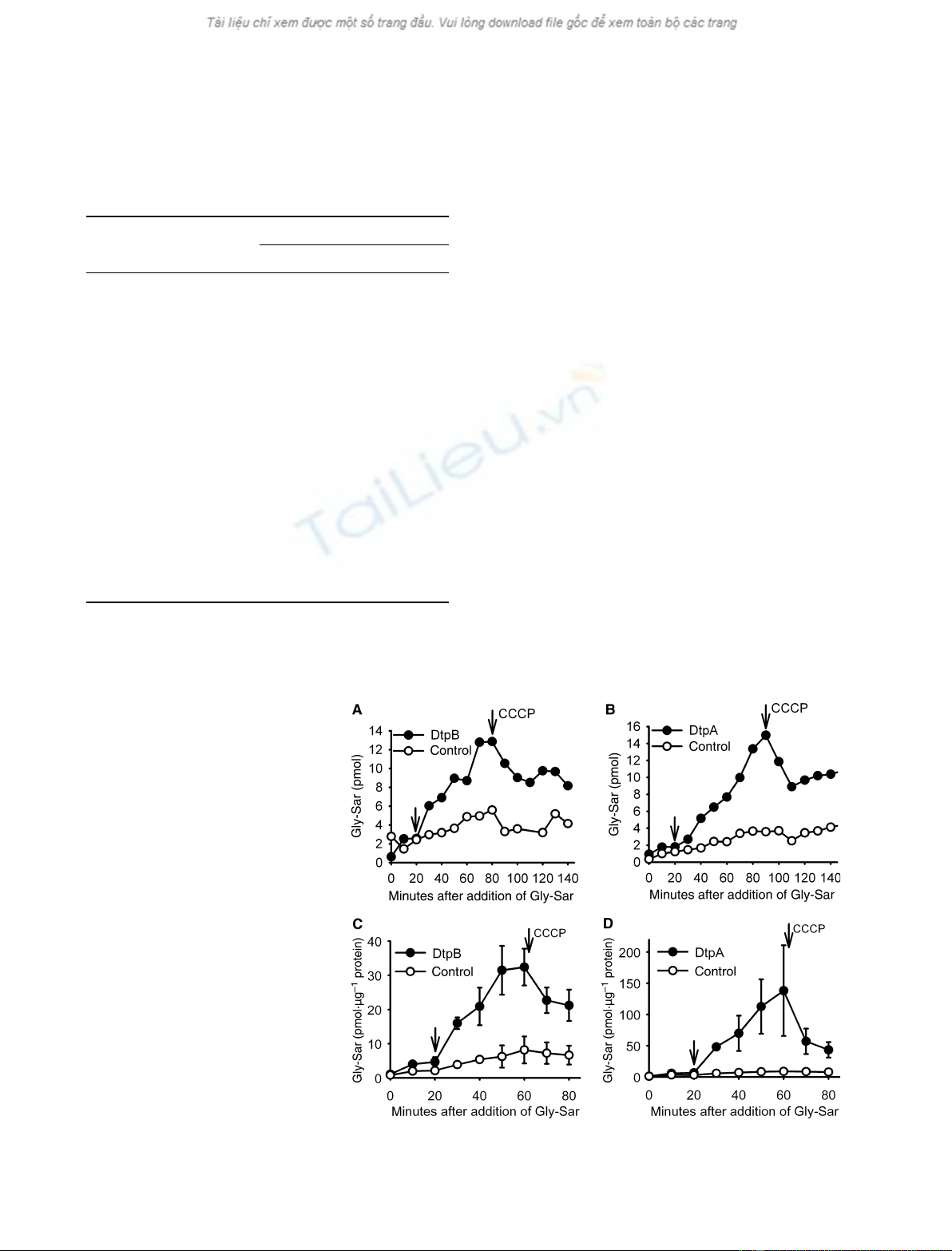

Reconstitution of DtpB and DtpA

Although transport inhibition by the protonophore

CCCP (Fig. 1E) already suggested H

+

-dependence, we

characterized the transport mode in more detail by

reconstitution in a cell-free system. Membranes of

E. coli containing the overproduced transport proteins

were fused with proteoliposomes containing bovine

cytochrome coxidase. A transmembrane proton gradi-

ent (inside negative) is generated when cytochrome c

oxidase is supplied with electrons, which are trans-

ferred from reduced ascorbate via N,N,N¢,N¢-tetram-

ethyl-p-phenylenediamine (TMPD) and cytochrome c.

Before addition of ascorbate, we observed a slow

influx of Gly-Sar into all types of vesicles. Addition of

ascorbate, however, caused a marked increase in Gly-

Sar influx into vesicles containing either DtpA or

DtpB, but not into control vesicles (Fig. 2A,B). Efflux

of Gly-Sar was observed when the proton gradient was

dissipated by addition of CCCP, indicating accumula-

tion of substrate above the extravesicular concentra-

tion in the presence of the proton gradient.

Table 1. Substrate specificity of DtpA and DtpB. Uptake of Gly-

Sar in % ± standard deviation (n‡2). Competitor was present at

a concentration of 10 mM(10-fold excess) except otherwise

indicated. The uptake time was 30 s. For DtpA, 100% = 200

pmolÆs

)1

ÆD

)1

. For DtpB, 100% = 50 pmolÆs

)1

ÆD

)1

. ND, not

determined.

Competitor

[

14

C]Gly-Sar uptake (%)

DtpA DtpB

None 100 ± 19 100 ± 11

Gly-Sar 27 ± 11

a

71 ± 12

a

Gly-Sar (100 mM)ND 32±6

a

Ala 76 ± 2 124 ± 20

Ala-Ala 1 ± 0

a

17 ± 3

a

Ala-Ala-Ala 1 ± 0

a

17 ± 3

a

Ala-Ala-Ala-Ala 78 ± 22 110 ± 20

L-Ala-D-Ala 63 ± 11

a

102 ± 3

D-Ala-L-Ala 5 ± 5

a

88 ± 3

D-Ala-D-Ala 84 ± 32 102 ± 3

Gly-Lys 90 ± 40 99 ± 2

Lys-Gly 2 ± 1

a

57 ± 12

a

Gly-Asp 26 ± 6

a

17 ± 1

a

Asp-Gly 54 ± 16

a

97 ± 5

Cefamandole 145 ± 50 101 ± 18

Cefuroxime 100 ± 2 99 ± 19

Cephradine 29 ± 5

a

57 ± 4

a

Cefalexin 35 ± 7

a

78 ± 2

a

Cefadroxil 19 ± 1

a

90 ± 23

a

Significant (P< 0.05) reduction relative to assay containing no

competitor.

Fig. 2. In vitro transport studies of DtpB

and DtpA. (A) Uptake of Gly-Sar (175 lM)in

membrane vesicles generated by fusion of

membranes from dtpB-overexpressing or

control cells with cytochrome coxidase-con-

taining proteoliposomes. After 20 min

(arrow), a proton gradient was established

by addition of a mix of ascor-

bate ⁄TMPD ⁄cytochrome cand destroyed

by addition of 10 lMCCCP as indicated. (B)

As (A), but with membranes of dtpA-over-

expressing cells (one of two similar experi-

ments). (C) Uptake of Gly-Sar (175 lM)in

liposomes containing purified DtpB and

cytochrome coxidase. After 20 min (arrow),

a proton gradient was established by addi-

tion of a mix of ascorbate ⁄TMPD ⁄cyto-

chrome cand destroyed by addition of

10 lMCCCP as indicated. n= 2, ± SD. (D)

As (C), with purified DtpA instead of DtpB.

n= 2, ± SD.

D. Harder et al. Proton-dependent peptide transporters of E. coli

FEBS Journal 275 (2008) 3290–3298 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS 3293

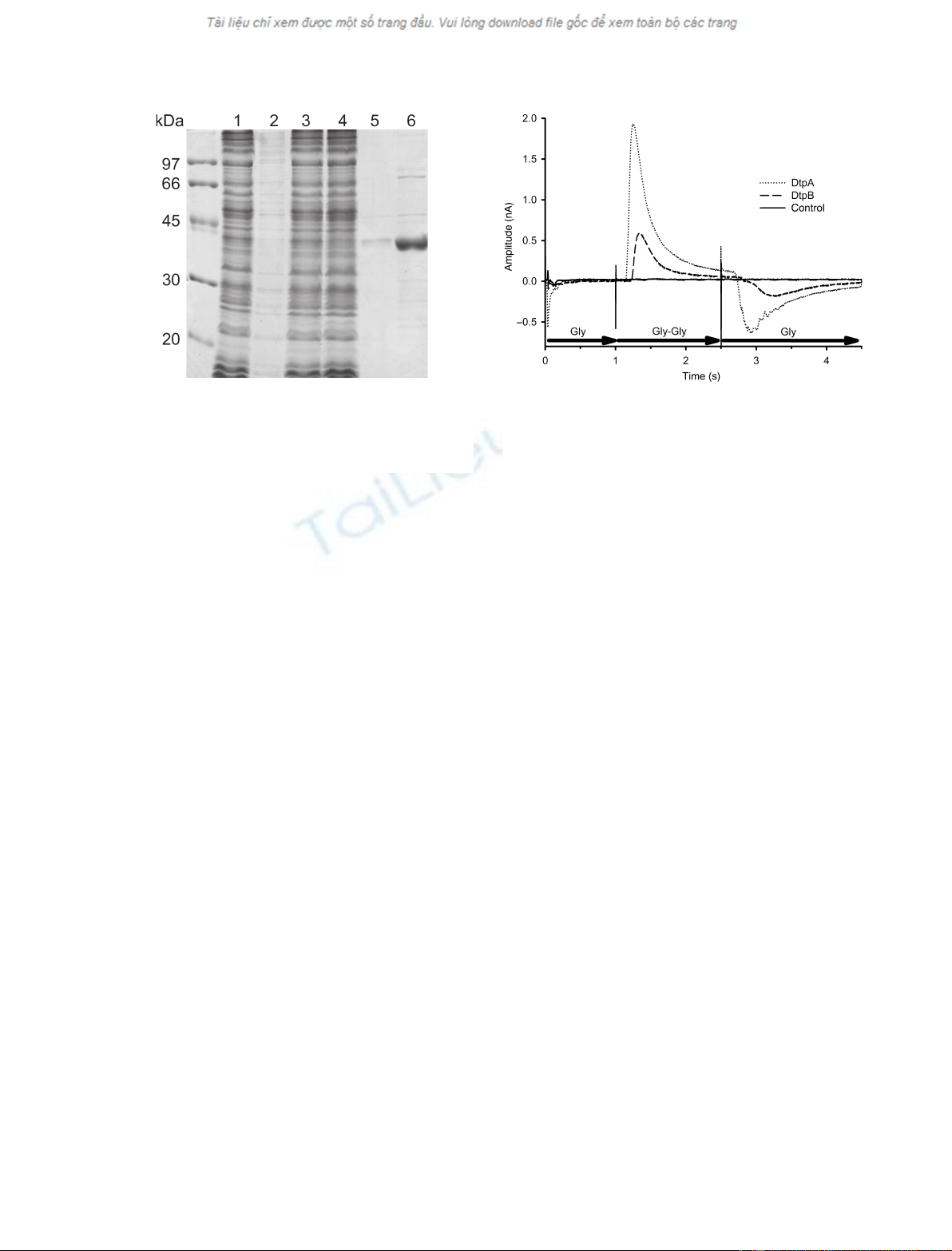

Next, we purified DtpB and DtpA from E. coli

membranes. The membranes were solubilized with the

detergent n-dodecyl-b-d-maltoside (DDM), and the

proteins were purified by metal-affinity chromato-

graphy, making use of the C-terminal His-tags. This

procedure yielded about 2–3 mg of relatively pure pro-

tein per liter of cell culture (Fig. 3). For reconstitution

into liposomes, the detergent was removed by adsorp-

tion to Bio-Beads. Subsequently, the liposomes contain-

ing the peptide transporters were fused with vesicles

containing cytochrome coxidase, using a freeze–thaw–

sonication cycle. Gly-Sar uptake after initiation of the

proton gradient increased almost 10-fold in the case of

DtpB and 60-fold in the case of DtpA (Fig. 2C,D), and

substrate efflux was observed after addition of CCCP.

To unequivocally demonstrate the electrogenic nature

of the transport process, we next used a chip-based

assay system, in which proteoliposomes containing

DtpB or DtpA were adsorbed onto a gold surface of

the SURFE

2

R

one

setup (IonGate Biosciences GmbH,

Frankfurt, Germany). This system is based on a solid-

support membrane technology, and allows detection of

capacity-coupled currents induced by movement of

charged molecules across a lipid bilayer [18,19]. After

adsorption of the proteoliposomes on the gold surface,

the SURFE

2

R

one

setup was used to let different buffers

flow for a certain time over this surface. Transport was

initiated by the exchange of a buffer containing Gly

(Gly included for charge and osmotic equilibration

only) against a buffer containing the dipeptide Gly-Gly.

Figure 4 shows that Gly-Gly induced significant cur-

rents in proteoliposomes containing DtpA or DtpB,

but not in control liposomes lacking the transport

proteins. The current spikes at the changing of the

buffer are artefacts of the working valves. The negative

current peaks observed after changing back to the Gly-

containing washing buffer most likely represent the

backflow of charges (Gly-Gly with protons) out of the

liposomes, as the substrate gradient is now reversed. As

the transport studies were performed with Na

+

-free

buffers at pH 7.0, the observed currents must originate

from proton movement coupled to dipeptide transloca-

tion in a symport mechanism. As in the cytochrome c

oxidase-energized vesicles, DtpA caused higher signals

than DtpB, suggesting that DtpA has a higher turnover

rate or higher stability in vitro.

Discussion

Despite the fact that peptide uptake in E. coli has been

studied for more than 20 years [1–3], essentially no

biochemical characterization has been performed on

any of the proteins. Another prokaryotic member of

the PTR family, DtpT from L. lactis, has been studied

in more detail, and some features of its membrane

topology are known [20]. With the focus on the four

E. coli genes that carry the typical PTR family motif

[11], we first cloned and overexpressed dtpA, and then

purified and characterized the corresponding protein

(DtpA ⁄TppB ⁄YdgR) [17]. Here we provide a detailed

functional analysis of DtpB as the second as yet

Fig. 3. Purification of DtpB. Coomassie-stained SDS gel (12.5%

acrylamide) of Ni

2+

–nitrilotriacetic acid purified DtpB. Lanes: (1)

DDM-solubilized membranes; (2) pellet after solubilization; (3)

supernatant after solubilization; (4) Ni

2+

–nitrilotriacetic acid flow-

through; (5) wash; (6) elution at about 150 mMimidazole.

Fig. 4. Electrophysiological experiment on proteoliposomes. The

electrical response of liposome-reconstituted DtpB (dashed line) or

DtpA (dotted line) to a change from a solution without substrate

(Gly) to a solution with substrate (Gly-Gly). The solid line shows the

recording from a sensor loaded with protein-free liposomes. The

current peaks indicate proton cotransport, and the negative peak is

back-flow of charges out of the liposomes (one of > 10 similar

experiments using ‡2 sensors).

Proton-dependent peptide transporters of E. coli D. Harder et al.

3294 FEBS Journal 275 (2008) 3290–3298 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS