http://www.iaeme.com/IJMET/index.asp 69 editor@iaeme.com

International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology (IJMET)

Volume 10, Issue 03, March 2019, pp. 69-79. Article ID: IJMET_10_03_007

Available online at http://www.iaeme.com/ijmet/issues.asp?JType=IJMET&VType=10&IType=3

ISSN Print: 0976-6340 and ISSN Online: 0976-6359

© IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed

STUDY ON PREDICTION OF MECHANICAL

PROPERTIES OF LARGE RING-SHAPED

FORGING DEPENDING ON COOLING RATE

J. H. Kang

Department of Aeromechanical Engineering, Jungwon University, South Korea

Y.C. Kwon

Korea Conformity laboratory, South Korea

ABSTRACT

Large ring-shaped forgings manufactured by ring rolling, as heavy as 10 tons, are

greatly affected by cooling. In the present study, controlled cooling was performed to

improve the mechanical properties of large ring-shaped forgings. To quantify cooling

rate, thermocouples were used to measure the cooling rate and the microstructures of

the products were observed during still air cooling, fan cooling, mist control cooling,

and water quenching. The temperature distribution measured in the four cooling

methods was used to calculate the heat transfer coefficient in each cooling method by

the inverse method. The mechanical properties were tested with specimens obtained

from the test block for each cooling method, and continuous cooling transformation

(CCT) curves were obtained by using measured microstructure contents. The

mechanical properties of the regions corresponding to the regions of the specimens

were calculated on the basis of the CCT curves and the heat transfer coefficients. The

experimental values and the analytical values of the strength of the products

manufactured by each cooling method were compared to verify that the mechanical

properties at each region of the products depending on the cooling methods may be

predicted

Keywords: Mechanical Property prediction, Large sized forging, cooling heat transfer

coefficient, Inverse method, CCT Curve.

Cite this Article: J. H. Kang and Y.C. Kwon, Study on Prediction of Mechanical

Properties of Large Ring-Shaped Forging Depending on Cooling Rate, International

Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology, 10(3), 2019, pp. 69-79.

http://www.iaeme.com/IJMET/issues.asp?JType=IJMET&VType=10&IType=3

1. INTRODUCTION

Large forgings show a mass effect due to the presence of a significant difference in the

cooling rate between the surface contacting a coolant and the core. Since larger forging

J. H. Kang and Y.C. Kwon

http://www.iaeme.com/IJMET/index.asp 70 editor@iaeme.com

products require longer cooling time due to the larger volume, their mechanical properties are

relatively poor in comparison with those of smaller forging products cooled by an identical

method. Therefore, it is difficult to use a simple normalizing process to satisfy the mechanical

properties required of large forgings due to the mass effect. Hence, micro-alloys are added or

the cooling rate is controlled to obtain the mechanical properties required of low carbon steel-

based forging products.[1]

Mechanical properties of steel materials, such as large forgings, are greatly affected by the

rate of cooling following heat treatment.[2] Since the cooling rate is determined by the

magnitude of the heat transfer coefficient between a coolant and the surface of the cooled

product, many studies have been conducted to quantify the cooling capacity depending on

cooling methods and coolants.

With the development of an analytical method based on the finite element method, the

inverse method has often been applied to calculate the heat transfer coefficients between

coolants and materials using the empirical temperature distribution. Chen et al. proposed

conjugate gradient inverse method is suitable for application to a rapid-heating or cooling

process comparing measured temperature and analysis results.[3] Kim and Oh developed an

inverse heat transfer formulation using two-dimensional finite element method and calculated

heat transfer coefficients with the measured temperature.[4] Buczek and Telejko determined

the values of the local heat transfer coefficient by inverse method for different quenching

conditions.[5] Sugianto et al. insisted zone-based heat transfer coefficient should be applied to

predict precise temperature distribution.[6] To calculated heat transfer coefficient considering

phase transformation, steel probe was developed and validated with the cooling tests of

various alloy steel. [7]

Buczek and Telejko tried to quantify the heat transfer coefficient using 2 kinds of oils and

various working conditions.[8] Pola et.al performed spray quenching tests for Ф840 heavy

forging and compared numerical simulation and experimental tests.[9] Zbigniew et al. applied

nonlinear shape function on inverse analysis to reduce the variation between finite element

analysis and measurements.[10]

Since the heat transfer coefficients in a thermal treatment process or TMCP(a

thermomechanical controlled processing) determine the mechanical properties of steel

products, the correlations among cooling rate, mechanical properties, and metal

microstructure have been important topics of experimental and analytical studies. The

relationship between Microstructure and Mechanical properties was investigated for various

forging steel after hot working and concluded that mechanical properties are influenced by the

microstructure due to cooling rate and hot working temperature.[11-14] Zaky et al. performed

different cooling test after hot forging to improve mechanical properties of micro-alloyed

steel. Air cooling after water quenching to 600℃ satisfied the target values and microstructure

composition.[15] Wu et al. investigated microstructural evolution depending cooling rate after

annealing process for cold rolled 1045 steel and verified the grain size of the rings becomes

smaller and the lamellar spacing of pearlite decreases as the annealing cooling rate increases,

resulting in a stronger and tougher material.[16] And the studies on the mechanical properties

improvement are performed using TMCP process on heavy plate and on low carbon bainitic

steel.[17-18]

The mechanical properties of large ring-shaped forgings manufactured using carbon steel

for general structural purposes need to be improved by means of grain size strengthening by

refining crystal grains though normalizing. While forging products are cooled by still air

cooling or fan cooling after normalizing thermal treatment, large forgings are cooled at a very

slow rate due to the mass effect, at a cooling rate even slower than that of the annealing

process for small products.[19] For this reason, the mechanical properties required of large

Study on Prediction of Mechanical Properties of Large Ring-Shaped Forging Depending on

Cooling Rate

http://www.iaeme.com/IJMET/index.asp 71 editor@iaeme.com

forgings are difficult to obtain only by still air cooling or fan cooling. The present study was

conducted to quantify the effect of cooling rates after normalizing on the mechanical

properties of large forgings. Experiments were performed with structural carbon steel of

different cooling methods, such as still air cooling, fan cooling, mist control cooling, and

water quenching to calculate the heat transfer coefficients by inverse method. And the tensile

strength, microstructure contents and grain size were measured with specimens obtained from

ring rolled forgings. The mechanical properties and grain size can be analyzed by Deform 3D

and Jmatpro software using calculated heat transfer coefficient and CCT curve. In this study,

the CCT curve was obtained by iterative method comparing measured strength and grain size

and calculated ones for different cooling method. The mechanical properties calculated by

obtained CCT curves and F.E analysis were compared with the experimental results to verify

the accuracy of analytical method.

2. COOLING TEST

Fig. 1 shows the shapes of the specimens obtained to measure the temperature of large forging

products made of carbon steel for general structural purposes. The material of the specimens

was EN10025 S355NL; the specimens were obtained from ring-shaped forgings formed by a

hot ring rolling process. To insert thermocouples for the measurement of temperature profiles

at different positions, 12.5 mm (location „a‟) and 130 mm (location „b‟) deep holes were

made. The temperature was measured using K-type thermocouples, which were sealed with

1/4 PT tap to prevent an inflow of the coolant into the materials in the cooling process. The

weight of the ring forging product before the sampling of the specimens was 12.7 tons. The

weight of the specimen block obtained from the ring forgings was 465 kg.

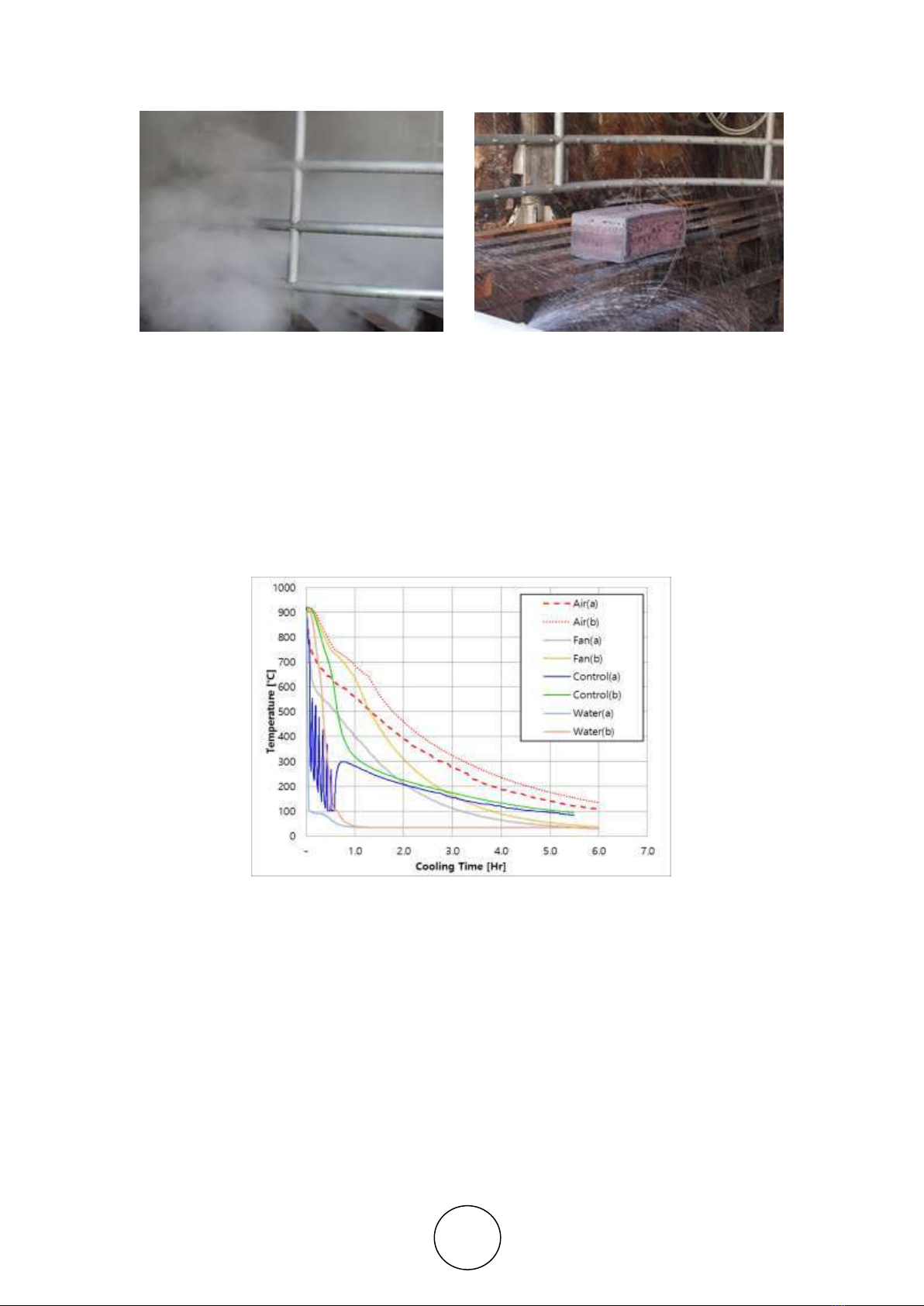

(a) Ring rolled forging product (b) Cooling specimen extracted from forging

Figure 1 Temperature measurement block of the forged ring

Four specimens were obtained from a ring forging and then processed to measure the

temperature profiles depending on the cooling conditions in different cooling methods,

including still air cooling, fan cooling, mist control cooling, and water quenching, following a

normalizing process, as the temperature was lowered from 900℃ to room temperature. The

process specimen block was charged into a heat treatment furnace, and cooling tests were

performed under different conditions. For fan cooling, a large cooling fan was used after

normalizing heat treatment. For mist control cooling, the specimen was extracted from the

furnace and moved to a cooling die; then, a cycle including three minutes spraying and three

minutes still air cooling was performed eight times to transfer the inside thermal energy to the

surface quickly and uniformly. Subsequently, still air cooling was performed. Water

quenching was performed for two hours by dipping the specimen block into a cooling bath at

40℃. Fig. 2 shows the methods of fan cooling and mist control cooling.

J. H. Kang and Y.C. Kwon

http://www.iaeme.com/IJMET/index.asp 72 editor@iaeme.com

(a) Spraying in control cooling (b) Spraying in control cooling(spray off)

Figure 2 cooling and mist control cooling

Fig. 3 shows the temperature distribution in different regions of the specimen obtained by

still air cooling, fan cooling, mist control cooling, and water quenching. As Fig. 3 shows, the

cooling rate increased in the order of still air cooling, fan cooling, mist control cooling, and

water quenching. While the cooling rate of mist control cooling, where mist cooling and still

air cooling were performed alternately, was faster than that of fan cooling down to 300℃, the

cooling rate in the still air cooling stage of mist control cooling below 300℃ was slower than

that of fan cooling.

Figure 3 Temperature distribution of the specimen measured by cooling tests.

3. TEST OF MECHACNICAL PROPERTIES OF SPECIMENS

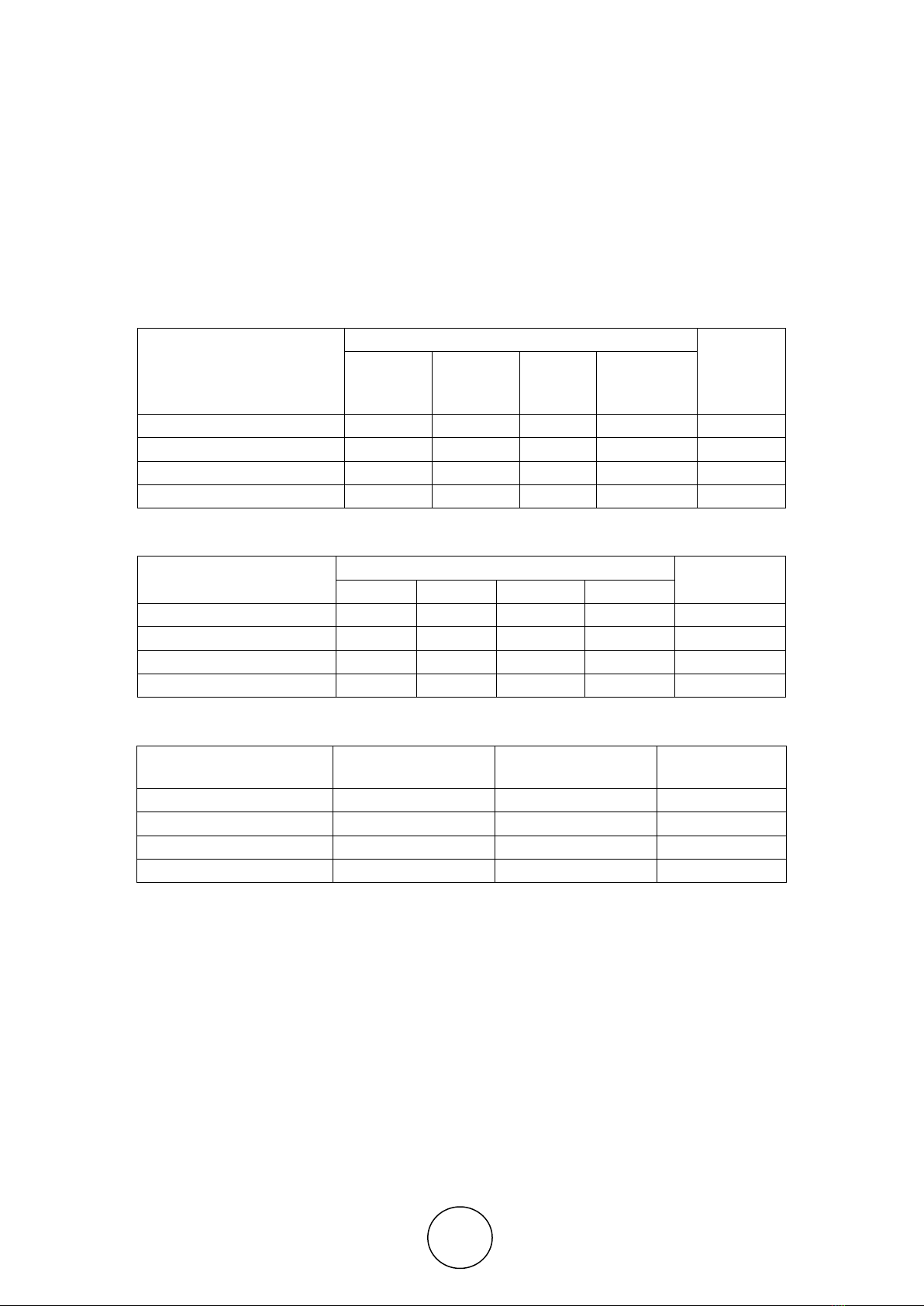

The mechanical properties of the specimens obtained from the cooling test block were

compared among the cooling methods by performing a tensile test and taking pictures of the

microstructures. The tensile tests were performed and the microstructure images were

obtained with respect to three specimens obtained at 1/2", which was the EN10025 specimen

sampling position, and the average values from the three specimens were tabulated. The test

specimens were prepared according to the ISO 862 specifications. Table 1 shows the yield

strength, tensile strength, elongation rate, and reduction of area obtained from the tensile tests

of the specimens cooled using the different cooling methods. As was predicted, the yield

strength of the specimens increased from 296 MPa to 304 MPa, 321.3 MPa, and 349.4 MPa as

the cooling rate increased. The tensile strength of the specimens also increased from 508.6

Study on Prediction of Mechanical Properties of Large Ring-Shaped Forging Depending on

Cooling Rate

http://www.iaeme.com/IJMET/index.asp 73 editor@iaeme.com

MPa to 515 MPa, 542.5 MPa, and 563.2 MPa as the cooling rate increased. On the contrary,

the elongation rate and the reduction of area decreased as the cooling rate increased, as shown

in Table 1.

Table 2 shows the room temperature impact toughness of the specimens obtained from the

position of 1/2" from the material surface and the grain size measured from the microstructure

images. The impact toughness and the ASTM number for the grain size increased as the

cooling rate increased.

Table 1 Mechanical properties depending on cooling methods

Method

Tensile Test

Remark

Yield

Strength

[MPa]

Tensile

Strength

[MPa]

Elong-

ation [%]

Reduction of

Area [%]

Still air Cooling

296.0

508.6

33.2

74.6

Forced air cooling

304.0

515.0

32.7

75.7

Mist control cooling

321.3

542.5

31.8

75.9

Water quenching

349.4

563.2

31.2

78.0

Table 2 Impact toughness and grain size

Method

Charpy Impact Test [J]

Grain Size

[ASTM]

1

2

3

Ave.

Still air Cooling

51.9

70.8

54.9

59.2

6.6

Forced air cooling

45.9

70.7

71.2

62.6

6.9

Mist control cooling

69.7

113.7

90.1

91.1

7.6

Water quenching

151.0

125.2

154.1

143.4

8.8

Table 3 Microstructure contents depending on the cooling methods

Cooling Method

Ferrite Contents

[%]

Pearlite Contents

[%]

Remark

Still air Cooling

63.8

36.2

Forced air cooling

57.0

43.0

Mist control cooling

55.3

44.7

Water quenching

50.2

49.8

Fig. 4 shows optical microscope images of the microstructure of the specimens obtained

from the position 1/2" from the surface depending on the cooling methods. Table 3 shows the

microstructure contents of individual specimens measured using the microstructure images.

The results show that the ferrite content decreased from 63.8% to 57%, 55.3%, and 50.2% as

the cooling rate increased. Neither martensite nor bainite microstructure was found even in

the water quenching specimens, because the cooling rate was slow due to the heavy weight of

the specimens and because the material of the specimens was low carbon steel.

![Giáo trình Solidworks nâng cao: Phần nâng cao [Full]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2026/20260128/cristianoronaldo02/135x160/62821769594561.jpg)

![Giáo trình Vật liệu cơ khí [mới nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20250909/oursky06/135x160/39741768921429.jpg)