P-ISSN 1859-3585 E-ISSN 2615-9619 https://jst-haui.vn LANGUAGE - CULTURE Vol. 60 - No. 10 (Oct 2024) HaUI Journal of Science and Technology

91

THE PRESENTATION OF ENGLISH AS A LINGUA FRANCA IN EMI CLASSROOMS

THỂ HIỆN CỦA TIẾNG ANH NHƯ NGÔN NGỮ QUỐC TẾ TRONG CÁC LỚP THUỘC CHƯƠNG TRÌNH ĐÀO TẠO BẰNG TIẾNG ANH (EMI) Phuong Thi Duyen1,*, Phuong Thi Thanh Huyen2 DOI: http://doi.org/10.57001/huih5804.2024.329 1. INTRODUCTION As English continues to dominate global communication, its role as a lingua franca in educational settings has become increasingly significant. In English-medium instruction (EMI) classrooms, where students and instructors come from diverse linguistic backgrounds, English serves as the common communicative tool. The use of English as a lingua franca (ELF) in EMI classrooms highlights the importance of intelligibility and flexibility over linguistic accuracy. This shift raises questions about how English is presented and utilized in such environments to facilitate learning and communication. ELF in the current study is based on Seidlhofer's definition outlined in “Understanding English as a Lingua Franca” [1]. Accordingly, ELF refers to “any use of English among speakers of different first languages for whom English ABSTRACT As English

increasingly serves as the global language of communication, its role in educational contexts has

evolved significantly. English as a lingua franca (ELF) has become a prominent feature in English-

medium instruction

(EMI) classrooms. This study examines how

English is presented and utilized as a lingua franca in EMI classrooms,

employing class observation as the primary data collection method. Through detailed analysis of classroom

interactions, the research explores the presentation of language, communicati

ve strategies, and the dynamics of

meaning-

making among students and lecturers. The findings reveal a flexible approach to language use that

prioritizes meaning over strict grammatical accuracy, highlighting the significance of multilingual resources and

code-

switching. Additionally, the study underscores the need for effective communication strategies that empower

students to articulate their ideas confidently. By contributing to the growing discourse on effective English language

use in globalized educati

onal settings, this research aims to inform pedagogical practices that enhance

communicative competence and support diverse linguistic backgrounds in EMI environments. Keywords: English as a lingua franca (ELF), English-medium instruction (EMI). TÓM TẮT Tiếng Anh ngày càng trở thành ngôn ngữ giao tiếp toàn cầu, vai trò của nó trong bối cảnh giáo dục đã có nhữ

ng

thay đổi đáng kể. Nghiên cứu này xem xét cách thể hiện và hiện thực hóa của tiếng Anh như một ngôn ngữ giao tiế

p

chung trong các lớp học EMI, sử dụng quan sát lớp học là phương pháp thu thập dữ liệ

u chính. Thông qua phân tích

chi tiết các tương tác trong lớp học, nghiên cứu khám phá cách thức trình bày ngôn ngữ, các chiến lược giao tiế

p và

động lực của việc tạo ra ý nghĩa giữa sinh viên và giảng viên. Các kết quả tìm được cho thấy một cách tiếp cậ

n linh

hoạt trong sử dụng ngôn ngữ, nhấn mạnh tầm quan trọng của tài nguyên đa ngôn ngữ và chuyển mã. Thêm vào

đó,

nghiên cứu nhấn mạnh nhu cầu về các chiến lược giao tiếp hiệu quả, giúp sinh viên tự tin diễn đạt ý tưởng củ

a mình.

Bằng cách đóng góp vào cuộc thảo luận ngày càng tăng về việc sử dụng tiếng Anh hiệu quả trong các bối cả

nh giáo

dục toàn cầu hóa, nghiên cứu này nhằm mục đích cung cấp cái nhìn cận cảnh về việc thể hiên và chiến lược giao tiế

p

trong các lớp học chuyên môn bằng tiếng Anh để từ đó các chuyên gia trong lĩnh vực tìm ra các ph

ương pháp sư

phạm nhằm nâng cao năng lực giao tiếp và hỗ trợ các nền tảng ngôn ngữ đa dạng trong môi trường EMI. Từ khóa: Tiếng Anh như một ngôn ngữ chung, chương trình đào tạo bằng tiếng Anh. 1School of Languages and Tourism, Hanoi University of Industry, Vietnam 2Faculty of English, FPT University, Hanoi, Vietnam *Email: duyenpt@haui.edu.vn Received: 09/9/2024 Revised: 23/10/2024 Accepted: 28/10/2024

VĂN HÓA https://jst-haui.vn Tạp chí Khoa học và Công nghệ Trường Đại học Công nghiệp Hà Nội Tập 60 - Số 10 (10/2024)

92

NGÔN NG

Ữ

P

-

ISSN 1859

-

3585

E

-

ISSN 2615

-

961

9

is the communicative medium of choice” (p.7). In such interactions, linguacultural norms are ad hoc and negotiated, with the primary objectives being intelligibility and communication. These interactions typically occur between non-native speakers of English or between mixed groups of non-native and native speakers, with key processes involving accommodation and adaptation. Studies worldwide underscore the complex role of English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) in global communication and cultural identity. Pakir uses Singapore as a case study to express concerns about English's dominance potentially eroding local languages while emphasizing the city’s multilingualism and the balance between global engagement and local identity [2]. Jenkins traces ELF’s evolution since its inception in 1996, highlighting its fluid, multilingual nature that interacts with various languages rather than being restricted to English alone [3]. Hua emphasizes the significance of negotiation in intercultural communication, stressing individual agency and the resources that participants bring to interactions [4]. Kecskes further examines whether current pragmatic theories adequately explain ELF communication, particularly regarding concepts like common ground and politeness, while debating the necessity for new theoretical frameworks or adjustments to existing ones in the absence of native speakers [5]. Together, these studies illuminate the dynamic and multifaceted nature of ELF, shaped by both local and global influences. In the context of EMI, recent research highlights various aspects of ELF across diverse educational settings. Yıldız, Soruç et al. investigate the difficulties faced by 83 students in Turkish EMI classrooms, identifying issues such as challenges with technical vocabulary, inadequate lecturer proficiency, and code-switching, alongside the need for improved vocabulary learning and language support systems [6]. Similarly, Li and Wu examine assessment practices among 40 Taiwanese EMI teachers, discovering a tendency to prioritize familiar techniques over instructional objectives, which points to a need for targeted training programs to enhance assessment methods [7]. In Austria, Smit explores classroom discourse from an ELF perspective, revealing that while EMI often appears monolingual, it effectively accommodates a culturally diverse student body, advocating for a combination of translanguaging and code-switching to highlight unique communication patterns [8]. In China, Jiang et al. focus on teachers' perceptions and practices, noting that, despite pragmatic strategies, the goal of enhancing English proficiency is often unmet due to insufficient emphasis on language teaching [9]. Further examining factors influencing EMI success, Rose et al. analyze data from 146 business students at a Japanese university, concluding that English language proficiency and academic skills significantly predict course performance, while motivation does not correlate with higher grades [10]. Xie and Curle support these findings through a mixed-methods study involving 100 students at a Chinese university, highlighting that perceived success and content-related language proficiency are crucial for academic achievement [11]. In Vietnam, there are various studies on ELF and EMI programs illuminate the complexities and implications of English language use in educational settings. Nguyen, Grainger et al. explore the pedagogical functions of English - Vietnamese code-switching, demonstrating its role in addressing challenges such as low proficiency and limited resources while enhancing classroom dynamics [12]. Vu examines authentic English interactions in the tourism sector, highlighting the flexibility of English usage in real-life contexts, a key aspect of ELF [13]. Tran and Tanemura provide a sociolinguistic profile of English in Vietnam, addressing its historical roles and current functions, along with learner attitudes [14]. Additionally, Nguyen, Walkinshaw et al. analyze EMI programs mandated under the National Foreign Languages 2020 project, identifying challenges at various levels and recommending improvements [15]. Nguyen further investigates high school science teachers' perceptions of EMI, noting its positive impact on English proficiency but also its detrimental effects on content coverage [16]. Tran and Nguyen advocate for equitable treatment of EMI and Vietnamese programs in higher education internationalization [17]. Also, Pham and Doan discuss the need for a more coordinated approach to EMI delivery, emphasizing the focus on domestic competitiveness over educational objectives [18]. Those are just some of the studies contributing to a deep understanding of ELF and EMI in Vietnam's evolving educational landscape. Despite the growing body of literature addressing ELF and its implications for communication and cultural identity in diverse contexts, there remains a significant research gap concerning its specific presentation and utilization within EMI classrooms. The current study explores the pedagogical strategies employed by instructors to manage linguistic diversity and investigates

P-ISSN 1859-3585 E-ISSN 2615-9619 https://jst-haui.vn LANGUAGE - CULTURE Vol. 60 - No. 10 (Oct 2024) HaUI Journal of Science and Technology

93

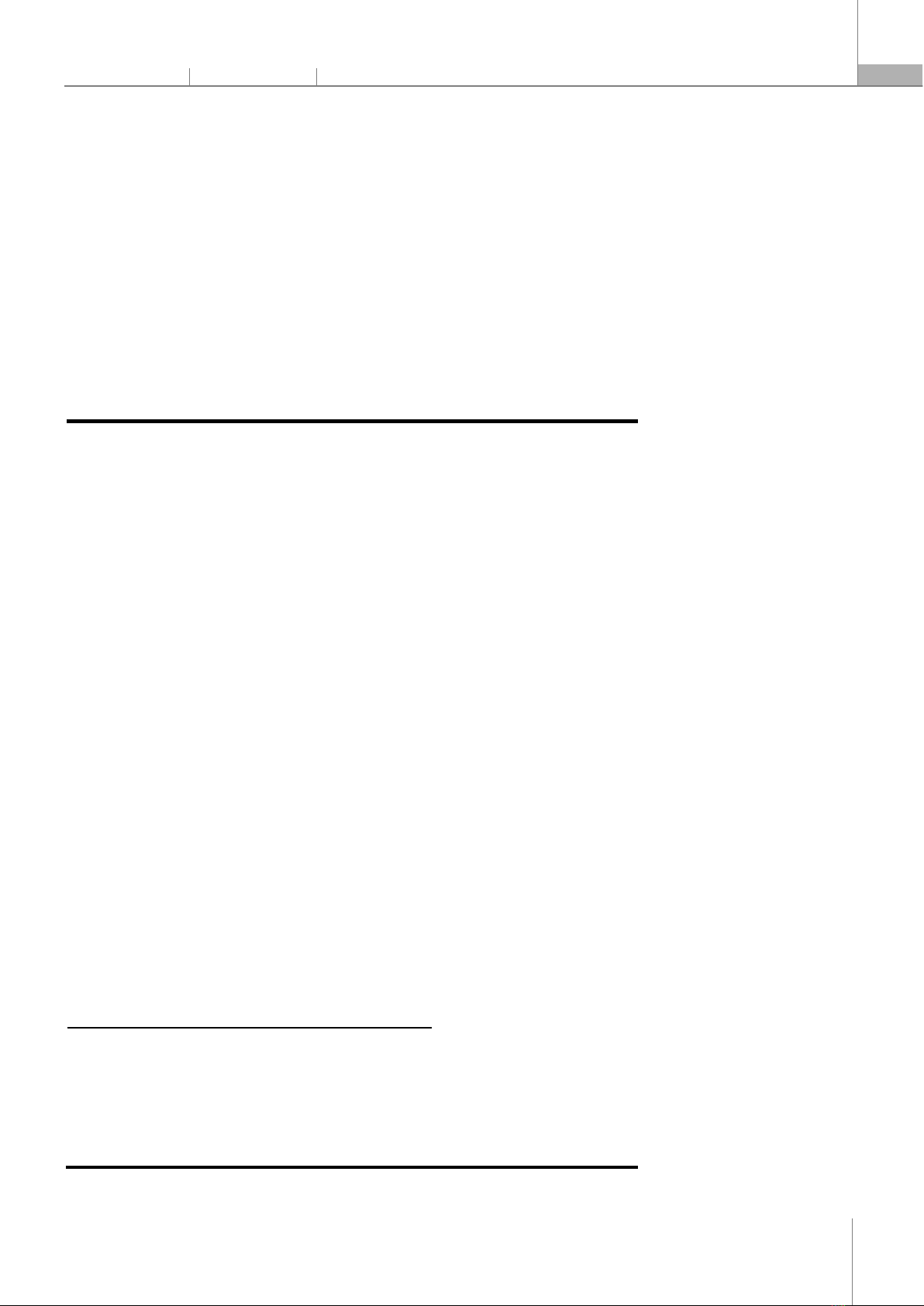

how students navigate and negotiate meaning using ELF. The study provides insights for policymakers, teacher trainers, lecturers, and researchers on EMI classroom dynamics. Our study target to find the answer for the following questions: 1. How is English presented in EMI classrooms? 2. What communicative strategies are used to enhance the effective communication in EMI classrooms? 2. REEARCH METHODS This study utilized classroom observation as the primary method for data collection. A total of fifteen lessons, encompassing a range of subjects taught by various instructors, were recorded with the explicit consent of both lecturers and students. These recordings were meticulously analyzed to extract relevant insights. An observation checklist was developed, drawing on recommendations from Ian MacKenzie’s "EFL in the Classroom" within the context of ELF [19]. MacKenzie highlights three essential perspectives for examining ELF in educational settings: language forms, communication strategies, language awareness, as well as assessment practices. Following the analysis, the data were coded into thematic categories, focusing on key elements of the instructors' use of English and the strategies employed to bridge linguistic diversity among participants. Documentation of these findings was conducted using Word files, ensuring that the confidentiality of all individuals involved was maintained. Personal identifiers for lecturers and students were anonymized through the use of codes, designating lecturers with “L” codes and students with “S” codes followed by corresponding numbers. 3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION 3.1. Classroom language presentation in EMI classrooms Table 1 provides a brief overview of the presentation of languages in EMI classrooms. As can be seen in Table 1, the presentation of language in EMI classrooms reveals the following characteristics including flexible use, Table 1. Language presentation in EMI classrooms Features of language Examples of used language Examples of lecturers' reaction Flexible use Tolerance with grammatical inaccuracies S1: We finish our project yesterday. It was good. Everyone do their part. L3: Continue with the new question Focus on conveying meaning S2: I no understand some parts of making payment procudure , so can I ask you?. Can you explain me, and so I understand better. L9: Answer S5's question without having any corection or notice for sudents Multilingual resources and code-switching Encouragement of the usage of resources in mother's language S3: use the book namely " Thanh toán quốc tế" and "International payment- Handouts for students" at the same time L1: Comment about a content of the Vietnamese version of the book and show a equivalent concept in English. Code-switching support S4: explain concept of high risk investment in Vietnamese to S2 then ask the lecturer a question about in English L7: Provide a case for student all to analyse as a demonstration and ask Ss to expain either in English or Vietnamese Collaborative meaning-making Paraphrasing, repeating key phrases S5: … revenue means the amount of money company earn, right? L5: Yup, revenue means the amount of money company earn a year Using gestures S6: ... Education sector in Vietnam is a huge profit business L12 stretches his hands outward to visually represent the magnitude of the profit, accompanied by the pronoun 'huge profit,' with a rising tone. Non-standard pronunciation tolerance S7: S is presenting on supply and demand: "ɪnflaiʃun" is when the price increase because of too much demand for goods." L3: Yes, that's correct. /ɪnfleɪʃən/ occurs when demand exceeds supply, leading…...... (The teacher uses the standard pronunciation, but without correcting or drawing attention to the student's non-standard version) Peer feedback and support (Pair work about sustainable tourism.) S8: In /sasteɪneibəl/ tourism, it's important for companies to protect the /envɪrənmənt/ and …..... S9. I think you mean/səsteɪnəbəl/ tourism and 'ɪnvaɪərənmənt,' not /envɪrənmənt/

VĂN HÓA https://jst-haui.vn Tạp chí Khoa học và Công nghệ Trường Đại học Công nghiệp Hà Nội Tập 60 - Số 10 (10/2024)

94

NGÔN NG

Ữ

P

-

ISSN 1859

-

3585

E

-

ISSN 2615

-

961

9

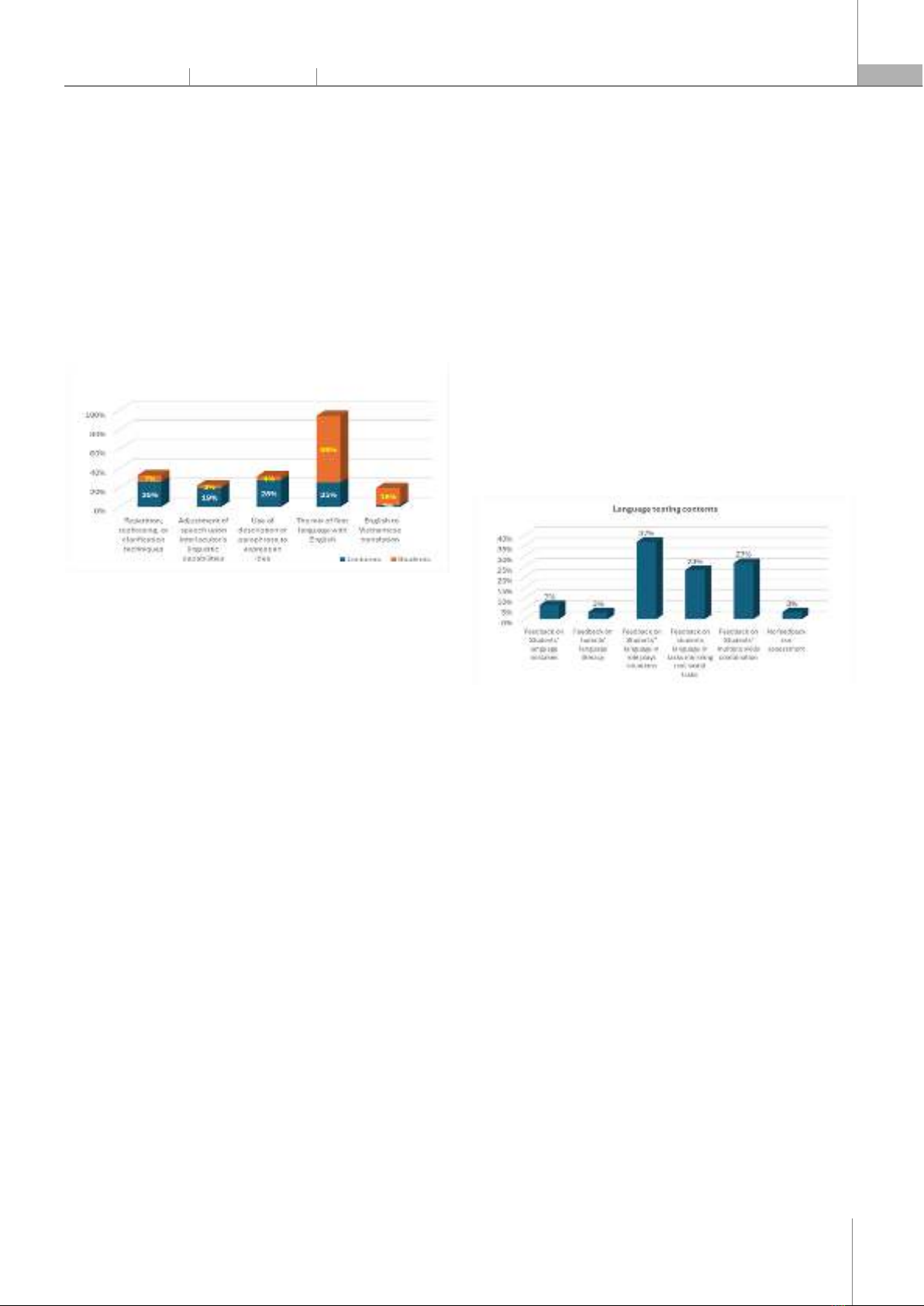

multilingual resources and code-switching, collaborative meaning-making, non-standard pronunciation tolerance and peer feedback support. The presentation of language often prioritizes flexibility and meaning-making over strict grammatical accuracy. Lecturers, generally, demonstrate tolerance for grammatical inaccuracies, as seen when a student says, “We finish our project yesterday. It was good. Everyone do their part.” The lecturer does not correct the errors but simply moves on to the next question, focusing on content rather than form. Similarly, the focus on conveying meaning is emphasized when students ask questions like, “I no understand some parts of making payment procedure,” and the lecturer provides an answer without correcting the student’s language, ensuring communication flows smoothly. The use of multilingual resources and code-switching is also encouraged, allowing students to use materials in both their native language and English. For instance, a student referencing both a Vietnamese book and an English handout is met with the lecturer providing equivalent concepts in English. Additionally, code-switching is supported when students explain concepts in Vietnamese and ask questions in English, with the lecturer offering flexibility in language choice for analysis tasks. Lastly, collaborative meaning-making is fostered through paraphrasing and repetition, as lecturers repeat and clarify key phrases like “revenue means the amount of money a company earns,” reinforcing students' understanding and creating a supportive learning environment. The commendable shift towards flexibility and meaning-making over strict adherence to grammatical rules fosters a more inclusive environment where students feel comfortable expressing themselves, even with non-standard language. The lecturers’ tolerance for grammatical inaccuracies reflects a commitment to ensuring that communication remains fluid and meaningful. Furthermore, the encouragement of multilingual resources and code-switching not only validates students' linguistic backgrounds but also enhances their comprehension and engagement. Overall, this strategy promotes collaborative learning and reinforces key concepts, ultimately creating a supportive atmosphere that benefits all learners. 3.2. Communication strategies in EMI classrooms According to MacKenzie, the strategies that enable speakers to engage in effective communication despite variations in grammar, pronunciation, and cultural conventions include negotiation of meaning, accommodation, paraphrasing, circumlocution, and code-switching. In the strategy of negotiation of meaning, speakers often employ techniques such as repetition, rephrasing, or clarification when they sense misunderstanding or ambiguity. Additionally, ELF speakers tend to adjust their speech based on their interlocutor's linguistic capabilities, simplifying vocabulary, slowing down their speech, or modifying grammatical structures to facilitate comprehension. Paraphrasing and circumlocution involve speakers describing or rephrasing ideas to convey their messages effectively. In some cases, ELF speakers may mix their first language with English - known as code-switching - to express themselves more clearly. The results presented in Figure 1 reflect the language strategies used by lecturers and students in the classroom. The analysis of communication strategies employed by lecturers and students in EMI classrooms reveals notable disparities in their approaches to effective communication. Lecturers predominantly use repetition, rephrasing, or clarification techniques (26%) to facilitate understanding among students, while students employ these strategies much less frequently (7%), indicating a potential lack of confidence in articulating their thoughts in English. Additionally, lecturers adjust their speech based on their interlocutor's linguistic capabilities 19% of the time, demonstrating awareness of diverse proficiency levels, whereas students show minimal adjustment (3%). When it comes to using descriptions or paraphrasing to express ideas, lecturers do so 28% of the time, whereas students only manage 4%, reflecting challenges in vocabulary or fluency. A striking finding is the high prevalence of code-switching among students (69%) compared to lecturers (25%), suggesting that students often mix their first language with English to enhance clarity. Furthermore, while lecturers rarely resort to English to Vietnamese translation (2%), students utilize this strategy more frequently (18%), indicating a reliance on translation to comprehend and express complex ideas. These patterns underscore the need for an inclusive classroom environment that fosters student participation and confidence in using English while recognizing the first language as a valuable resource for learning. To enhance communication, it is crucial to equip students with strategies to improve their rephrasing and clarification skills, ultimately creating a more interactive and effective learning environment. This section on communication strategies in EMI classrooms emphasizes the importance of negotiation of meaning, accommodation, paraphrasing, circumlocution,

P-ISSN 1859-3585 E-ISSN 2615-9619 https://jst-haui.vn LANGUAGE - CULTURE Vol. 60 - No. 10 (Oct 2024) HaUI Journal of Science and Technology

95

and code-switching for effective interaction. The observed disparities, especially the lower use of these strategies by students, highlight a need for greater confidence and skill development in expressing ideas in English. The prevalence of code-switching indicates students’ reliance on their first language for clarity, underscoring the importance of valuing linguistic diversity. By creating an inclusive environment that encourages participation and equips students with practical strategies, educators can enhance communication and improve students’ proficiency and comfort in using English academically Figure 1. Language strategies in EMI classrooms 3.3. Language testing in EMI classrooms The lecturers’ assessment activities in EMI classroom is shown in Chart…. The data reveals a diverse approach to language assessment, with feedback on students' language use during role play situations comprising the most substantial portion at 37%. This indicates a strong emphasis on practical communication skills, aligning with MacKenzie’s advocacy for contextually relevant assessments that reflect real-world interactions. Furthermore, feedback on students' combination of multiple skills, such as listening to a peer’s presentation then making a group discussion about the content, accounts for 27%, highlighting the importance of integrated language use, which MacKenzie suggests is crucial for fostering communicative competence. In contrast, feedback on language literacy, including pronunciation and grammar, is notably lower at 3%. The feedback on students’ language in tasks mirroring real-world such as writing a business email, making a reservation…, at 23%, further reinforces the classroom's focus on authentic language use, yet the minimal emphasis on correcting language mistakes (7%). However, the absence of feedback in 3% of cases raise concerns about the overall effectiveness of the assessment strategy. This distribution emphasizes the focus of lecturers on communicative competence in language testing involves assessing not just the linguistic accuracy of a learner but also their ability to use the language effectively in real-life situations. In short, EMI classroom assessments prioritize practical communication skills and the integration of multiple language competencies in real-world contexts. By focusing on role-play scenarios and authentic tasks, lecturers align their evaluation methods with the goal of fostering effective communicative competence. However, the limited feedback on language literacy and minimal attention to grammatical errors indicate a potential gap in addressing foundational language skills. To enhance assessment effectiveness, it is essential to strike a balance between practical application and support for linguistic accuracy. This approach will ensure that students are equipped for both communicative success and overall language proficiency. Figure 2. Testing activities in EMI classrooms The findings of this study underscore the importance of adopting a flexible and communicative approach in EMI classrooms, emphasizing meaning-making over grammatical precision. To enhance this approach, professional development for educators is essential, focusing on effective communication strategies and the integration of multilingual resources. Additionally, institutions should provide targeted support to help students develop their English communication skills, boosting their confidence and fluency. Collaborative learning strategies, such as group discussions and peer feedback, should be emphasized to engage students and facilitate their articulation of ideas. Furthermore, curricula must incorporate multilingual resources, allowing students to leverage their native languages alongside English for better comprehension. Language assessments should prioritize real-world applications and communicative competence, reflecting the practical skills necessary for future professional environments. Finally, fostering a classroom culture that values linguistic diversity and encourages risk-taking can significantly improve student

![Đề cương môn Tiếng Anh 1 [Chuẩn Nhất/Mới Nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20251130/cubabep141@gmail.com/135x160/51711764555685.jpg)

![Mẫu thư Tiếng Anh: Tài liệu [Mô tả chi tiết hơn về loại tài liệu hoặc mục đích sử dụng]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20250814/vinhsannguyenphuc@gmail.com/135x160/71321755225259.jpg)