http://www.iaeme.com/IJMET/index.asp 1135 editor@iaeme.com

International Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology (IJMET)

Volume 10, Issue 03, March 2019, pp. 1135–1145, Article ID: IJMET_10_03_116

Available online at http://www.iaeme.com/ijmet/issues.asp?JType=IJMET&VType=10&IType=3

ISSN Print: 0976-6340 and ISSN Online: 0976-6359

© IAEME Publication Scopus Indexed

SIMULATION OF HEAT EXCHANGE BETWEEN

TRANSMISSION UNITS OF AN AUTOMOTIVE

TRUCK

Dolgushin А.А.

Candidate of Technical Sciences, Assistant Professor, Novosibirsk State Agricultural

University, Novosibirsk, Russian Federation

Voronin D.M.

Doctor of Technical Sciences, Professor, Novosibirsk State Agricultural University,

Novosibirsk, Russian Federation

Mamonov O.V.

Lecturer, Novosibirsk State Agricultural University, Novosibirsk, Russian Federation

ABSTRACT

This article details the approach to minimize energy expenditures when using

vehicle transmissions. This approach comprises certain mathematical simulation

techniques which help to study and minimize energy expenditures of transmission unit

systems. The use of mathematical simulation, when defining an optimum temperature of

a transmission unit system, is based on comparison of stabilization temperatures in real

conditions, changeover points and optimum temperatures of transmission units. As a

criterion of optimization, we suggest using minimization of a resource expenditure

function for a whole system of units. This article details possible variants of heat

interaction between units and provides guidelines for achieving a target changeover

point of a vehicle transmission. We studied possible variants of heat interaction between

units and provided recommendations for achieving a target changeover point of a

vehicle transmission.

Key words: transmission, heat interaction between units, heat exchange simulation,

optimum temperature, changeover point, heat distribution.

Cite this Article: Dolgushin А.А., Voronin D.M., Mamonov O.V., Simulation of

Heat Exchange Between Transmission Units of an Automotive Truck, International

Journal of Mechanical Engineering and Technology 10(3), 2019, pp. 1135–1145.

http://www.iaeme.com/IJMET/issues.asp?JType=IJMET&VType=10&IType=3

1. INTRODUCTION

Nowadays, vehicle efficiency is determined by the amount of resources spent and the volume

of wastes produced per run unit of work unit. The main consumable resource is energy

generated by an IC engine by burning engine fuel. The amount of consumable fuel depends on

Simulation of Heat Exchange Between Transmission Units of an Automotive Truck

http://www.iaeme.com/IJMET/index.asp 1136 editor@iaeme.com

the amount of work and energy losses in transmission units. Besides, the amount of combustible

fuel determines the amount of hazardous substances emitted by a vehicle to the environment

along with exhaust gases. This gets even worse at low temperatures as lubrication oil viscosity

is higher.

Based on the research findings [1,2], using vehicles under subzero conditions increases

engine fuel consumption by 7–9 %. Research by W. Frank shows a significant increase in CO2

emission at subzero temperatures [3]. According to research data [4], when ambient temperature

reaches 20 С below zero, CO2 emissions from a moving vehicle increase by 5 %. Furthermore,

the need for additional engine warm-up leads to additional emissions of pollutants [5].

Despite of numerous studies on resource saving during use of vehicles, energy losses

associated with operation of transmission units were considered negligible, and most of these

studies focus on ways to increase engine efficiency. However, continuous increase in costs of

energy resources, environmental law enforcement and higher penalties for contamination of the

environment make researchers to turn their attention to operational efficiency of transmission

units. According to the given data [6], one light motor vehicle consumes an average of 340 l of

engine fuel per year to overcome friction forces in transmission units. Given the number of

vehicles in the world, they consume up to 208 000 m litres of gasoline and diesel fuel to

overcome friction forces.

Studies of energy transfer through transmission reduction gears show that mechanical

friction in gears and oil churning are the main reasons for energy losses [7,8]. At positive

temperatures 52 % of total losses comes to mechanical friction, and 40 % to oil churning [9].

At subzero temperatures the percentage of losses due to oil churning and splashing rises, as oil

viscosity is higher.

At the current level of science and technology it is obviously impossible to avoid power

losses in transmission units. However, some works [10,11] indicate there is potentially a

possibility to reduce losses up to 50 %.

One of the ways to do that is to improve design of transmission reduction gears. According

to the work [12], replacing standard spur gears with skew gears leads to a successful energy

loss reduction. Use of gears with shorter teeth helps to reduce friction and decrease unit

temperature by 20 %.

From the perspective of vehicle owners, methods which would help to reduce losses in real

operating conditions are of most interest. Among them is the use of low-viscosity lubrication

oils. Replacing the standard oil with a test oil helped to reduce friction in gears by 16–19 %

[13]. However, this result occurs only in a limited temperature range.

Another way to reduce power losses is regulation of a thermal regime of transmission units

by using various technical devices. In production environment, we usually talk about external

sources of thermal energy which can use vapour-air mixture [14] or exhaust gas heat [15] as

heat conductor.

The work [16] proves that the critical factor for reduction of power losses in transmission

is monitoring and ensuring the thermal regime of all transmission units. At the first stage, the

solution comprises justification of the optimum thermal operating regime of transmission

reduction gears in terms of energy expenditures. The work [17] determines an optimum regime

as a thermal regime of a unit which correlates with minimum energy resource expenditures to

ensure this thermal regime and resource expenditures to overcome a friction torque in the unit.

At the second stage, there is a need to justify a temperature range of units which ensures

minimum resource expenditures, as well as to develop a strategy to achieve these temperatures

within the transmission unit system.

Dolgushin А.А., Voronin D.M., Mamonov O.V.

http://www.iaeme.com/IJMET/index.asp 1137 editor@iaeme.com

The objective of this work is to develop mathematical models of heat exchange between

transmission units which would help to simulate thermal interaction within the unit system,

justify target temperature levels and the strategy to achieve them.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

Apart from the optimum operating regime of a unit, other important features are steady running

conditions of the unit and its temperature stabilization regime. The stabilization regime of a unit

is characterized by some conditional temperature constancy. By the stabilization regime we

mean an operating regime of a unit characterized by equality between heat, that enters the unit,

and heat that goes from its surface to the environment. The stabilization temperature value

depends on environmental conditions, operating regime of the unit, design and configuration of

the transmission, etc.

Beside two temperature regimes, we have to take into consideration minimum and

maximum operating temperatures of a unit. If stabilization and optimization temperatures go

beyond allowable operating regimes, then minimization and stabilization regimes should not be

considered while minimizing expenditures. Some adjustments in terms of expenditure

minimization should be made here, keeping in mind that these adjustments should be directed

towards optimization.

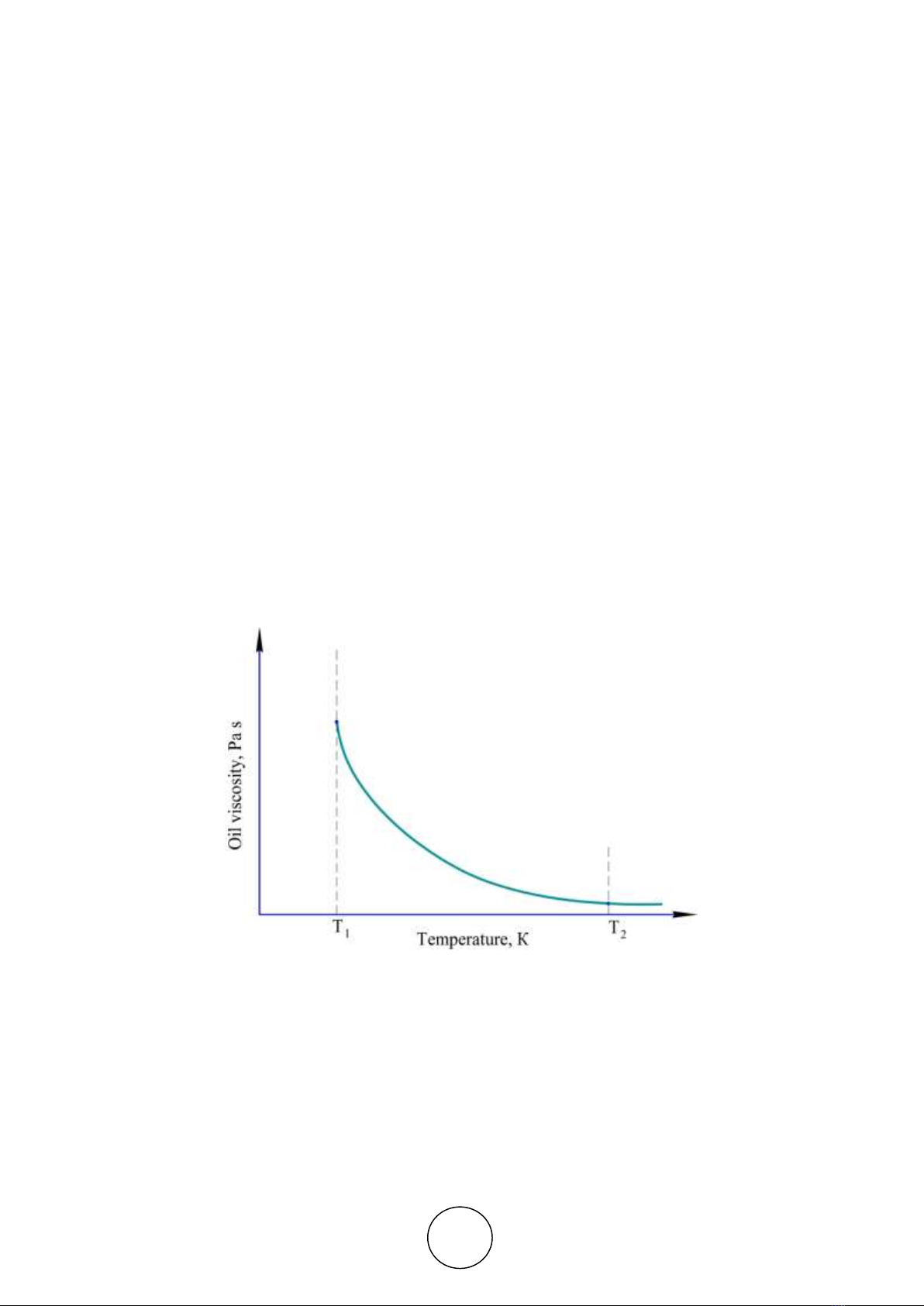

Temperature limitations are conditioned by viscosity-temperature properties of the lubricant

oil used in transmission. In general, the temperature range is limited by the oil temperature that

corresponds with the minimum oil viscosity needed for an accident-free start of a vehicle and

by the oil temperature that causes a significant decrease in viscosity change rate accompanied

by a temperature raise (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Dependency of oil viscosity on temperature — General View

In these conditions, if the target optimum temperature of a reduction gear is lower than the

final pre-heat temperature Тopt≤Т1, then Т1 shall be considered the optimum temperature. If the

equation is Тopt≥Т2, then Т2 shall be considered optimum.

We take the stabilization regime as an initial operating regime. Expenditures are minimized

when the unit temperature goes from the stabilization temperature to the temperature needed

for expenditure optimization. Here we shall make some adjustments within allowable regimes.

Each unit has its optimum temperature regime, conditioned by the intent of the given unit

and its performance features. To ensure such temperature regime means to use the unit to its

Simulation of Heat Exchange Between Transmission Units of an Automotive Truck

http://www.iaeme.com/IJMET/index.asp 1138 editor@iaeme.com

full capacity. The optimum thermal regime of a unit is however just conditionally optimum,

and reflects neither real work of the unit nor its interaction with other units. That is why

determination and further maintenance of the rational thermal regime of vehicle units as a whole

are important, both scientifically and practically.

This being so, a system is divided into subsystems, and it is expected that thermal regime

affects only subsystem units. Each subsystem in its thermal regime may be looked at

independently.

Let's divide a system of units into subsystems with observationally equivalent thermal

regimes. Then define a resource expenditure function for the whole system:

S=S(x1;x2;…,xn)=S1(x1;x2;…,xn)+S2(x1;x2;…,xn)+…+Sk(x1;x2;…,xn), (1)

where:

x1, x2, … , xn – are values, representing thermal regimes of units;

Sj (x1;x2;…;xn) – expenditure functions for various resources;

j=1, 2, …, k are types of resources used to ensure the thermal regime.

Expenditures (1) are determined for the following constraint system:

{

Тmin

(1) ≤Т (1)(x1;x2;…,xn) ≤ Тmax

(1)

Тmin

(2) ≤ Т(2)(x1;x2;…,xn) ≤ Тmax

(2)

…

Тmin

(m) ≤ Т(m)(x1;x2;…,xn) ≤ Тmax

(m)

(2)

where:

Т(i) (x1; x2; … ; xn) – are thermal regimes of units, i=1, 2, …, m;

Тmin(i) and Тmax(i) – are minimum and maximum temperature values of given units, i=1, 2, …,

m.

Via Ti (temperature of the i-unit) we can determine S(i) — total costs of using the i-unit at

the unit's temperature Ti, i=1, 2, …, m. Thus, minimization of resource expenditures involves

determination of temperature intervals from Тi(1) to Тi(2) for each unit. Achievement of such

interval during heat exchange will lead to minimization of all resource expenditures

S=S(x1;x2;…,xn).

While studying thermal regimes of a vehicle, we used simulation methodology at large.

Taking into consideration operating features and characteristics of units, we used methods of

mathematical simulation to design a math model of thermal regimes of units included into an

airtight unit system. Optimization of thermal regimes of transmission units was performed with

respect to minimization of resource expenditures. By using an expenditure function analysis

technique and mathematical analysis methods, we managed to determine the way this function

changes depending on a thermal regime of each particular unit and a system of units as a whole.

Relying on the methods of determination of the object system temperature, we defined

changeover points of a system of units in various states and with various system features.

3. FINDINGS AND CONSIDERATIONS

To determine thermal operating regimes of units let's discuss temperature characteristics of each

unit and relations between them. It is worth reminding that we talk about four characteristics

here: optimum regime temperature, stabilization regime temperature, temperature interval of

operation, minimum and maximum operating temperatures of a unit. Let's label them

respectively: Тi

opt, Тi

stabil, Тi

min, Тi

max. For each unit we also determine its current temperature in

real time t: Ti (t). Further on, if the time is not specified, the temperature of a unit will be Ti.

Dolgushin А.А., Voronin D.M., Mamonov O.V.

http://www.iaeme.com/IJMET/index.asp 1139 editor@iaeme.com

Thermal regimes are marked on the 0Ti axis (unit temperature), Fig. 2. The figure also shows

the direction of total expenditure decrease from Тi

stabil to Тi

opt.

Figure 2. Thermal regimes of the i-unit and direction of total expenditure decrease

The Figure 2 illustrates the case when optimum and stabilization operating regimes of a unit

are within an allowable range. Let's discuss cases when this requirement is not met, e.g. when

Тiopt≤Тistabil.

When there is no overlap between the allowable regime interval [Тimin;Тimax] and the

optimum-stabilization temperature regime interval [Тiopt;Тistabil], then the allowable regime

interval shall be considered optimum.

The direction of expenditure decrease depends on the position of intervals. If the interval

[Тiopt;Тistabil] lies to the left of the interval [Тimin;Тimax] (Fig. 3), the direction shall be from Тimax

to Тimin. If the interval [Тiopt;Тistabil] is to the right of [Тimin;Тimax], then expenditure

minimization is from Тimin to Тimax (Fig. 4). The case when Тiопт>Тiст does not affect the approach

to determination of the direction of expenditure decrease.

Figure 3 Thermal regimes of the i-unit when the interval [Тiopt;Тistabil] is to the left of [Тimin;Тimax]

Figure 4 Thermal regimes of the i-unit when the interval [Тiopt;Тistabil] is to the right of [Тimin;Тimax]

Let's now discuss overlapping of intervals.

Assume that Тiopt≤Тistabil. In this case heat exchange is controlled by decreasing temperature

of a unit (heat transfer or cooling). Here, the minimum optimization interval value is max

(Тi

min;Тi

opt), and the maximum value is min(Тi

max;Тi

stabil).

If Тiopt>Тistabil, then control is performed by increasing the unit temperature (heat input or

warm-up). The minimum optimization interval value is max (Тi

min;Тi

stabil), and the maximum

value is min(Тi

max;Тi

opt).

![Bài tập trắc nghiệm Kỹ thuật nhiệt [mới nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20250613/laphong0906/135x160/72191768292573.jpg)

![Bài tập Kỹ thuật nhiệt [Tổng hợp]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20250613/laphong0906/135x160/64951768292574.jpg)

![Bài giảng Năng lượng mới và tái tạo cơ sở [Chuẩn SEO]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2024/20240108/elysale10/135x160/16861767857074.jpg)