Reporting study results 87

6 Simpson AG. A comparison of the ability of cranial ultrasound, neonatal neuro-

logical assessment and observation of spontaneous movements to predict out-

come in preterm infants University of Sheffi eld; 2004.

7 Diggle PJ, Heagerty P, Liang K-J, Zeger SL. Analysis of longitudinal data, 2nd ed.

Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2002.

8 Matthews JNS, Altman DG, Campbell MJ, Royston P. Analysis of serial measure-

ments in medical research. British Medical Journal 1990;300:230–5.

9 Moher D, Schulz KF, Altman DG, for the CONSORT Group. The CONSORT

statement: revised recommendations for improving the quality of reports of par-

allel group randomised trials. Lancet 2001;357:1191–4.

10 Altman DG. Practical statistics for medical research. London: Chapman & Hall;

1991.

11 Kapoor AS, Kanji H, Buckingham J, Devereaux PJ, McAlister FA. Strength of evi-

dence for perioperative use of statins to reduce cardiovascular risk: systematic

review of controlled studies. British Medical Journal 2006;333:1149–55.

12 Deeks JJ, Everitt B. Forest plot. In: Everitt B, Palmer C, editors. The encyclopaedic

companion to medical statistics. London: Arnold; 2005.

13 Deeks JJ. Funnel plots. In: Everitt B, Palmer C, editors. The encyclopaedic compan-

ion to medical statistics. London: Arnold; 2005.

14 Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schnieder M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected

by a simple graphical method. British Medical Journal 1997;315:629–34.

88 How to Display Data

Appendix

Table A7.1 CONSORT checklist of items to include when reporting a randomised trial9

Item No. Descriptor

Title and abstract 1 How patients were allocated to interventions.

Introduction

Background 2 Scientifi c background and explanation of rationale.

Methods

Participants 3 Eligibility criteria for participants and the settings

and locations where the data were collected.

Interventions 4 Precise details of the interventions intended for

each group and how and when they were actually

administered.

Objectives 5 Specifi c objectives and hypotheses.

Outcomes 6 Clearly defi ned primary and secondary outcome

measures and, when applicable, any methods

used to enhance the quality of measurements

(e.g. multiple observations, training of assessors).

Sample size 7 How sample size was determined and, when

applicable, explanation of any interim analyses and

stopping rules.

Randomisation

Sequence 8 Method used to generate the random allocation

generation sequence, including details of any restriction

(e.g. blocking, stratifi cation).

Allocation 9 Method used to implement the random allocation

concealment sequence (e.g. numbered containers or central

telephone), clarifying whether the sequence was

concealed until interventions were assigned.

Implementation 10 Who generated the allocation sequence, who

enrolled participants and who assigned participants

to their groups.

Blinding (masking) 11 Whether or not participants, those administering

the interventions, and those assessing the

outcomes were blinded to group assignment.

When relevant, how the success of blinding was

evaluated.

Statistical methods 12 Statistical methods used to compare groups for

primary outcome(s). Methods for additional

analyses, such as subgroup analyses and adjusted

analyses.

(Continued)

Reporting study results 89

Table A7.1 (Continued.)

Item No. Descriptor

Results

Participant fl ow 13 Flow of participants through each stage

(a diagram is strongly recommended). Specifi cally,

for each group report the numbers of participants

randomly assigned, receiving intended treatment,

completing the study protocol and analysed for

the primary outcome. Describe protocol deviations

from study as planned, together with reasons.

Recruitment 14 Dates defi ning the periods of recruitment and

follow-up.

Baseline data 15 Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics

of each group.

Numbers analysed 16 Number of participants (denominator) in each

group included in each analysis and whether the

analysis was by ‘intention-to-treat’. State the

results in absolute numbers when feasible

(e.g. 10/20, not 50%).

Outcomes and 17 For each primary and secondary outcome, a

estimation summary of results for each group, and the

estimated effect size and its precision (e.g. 95%

confi dence interval).

Ancillary analyses 18 Address multiplicity by reporting any other

analyses performed, including subgroup analyses

and adjusted analyses, indicating those

pre-specifi ed and those exploratory.

Adverse events 19 Address multiplicity by reporting any other

analyses performed, including subgroup analyses

and adjusted analyses, indicating those

pre-specifi ed and those exploratory.

Discussion

Interpretation 20 Interpretation of results, taking into account study

hypotheses, sources of potential bias or imprecision

and the dangers associated with multiplicity of

analyses and outcomes.

Generalisability 21 Generalisability (external validity) of the trial

fi ndings.

Overall evidence 22 General interpretation of the results in the context

of current evidence.

90

Chapter 8 Time series plots and

survival curves

8.1 Introduction

This chapter outlines good practice when displaying data that are ordered in

time. These data can arise either as a result of the monitoring of a particular

event or events across a population over time (time series) or following up

individuals over time to measure their time to a particular event (survival

analysis). This chapter is not concerned with repeated measures outcome

data as they have already been dealt with in Chapter 7.

8.2 Time series plots

A time series is a series of observations ordered in time. It differs from

the repeated measures data discussed in the previous chapter in two

ways:

1 Usually there is only one replication of the data, for example one subject’s

heart rate monitored over time, or the annual death rates of one country

over time. With repeated measures we have more than one subject under

consideration.

2 There are many time points. Typically in patient monitoring thousands

of points are sampled.

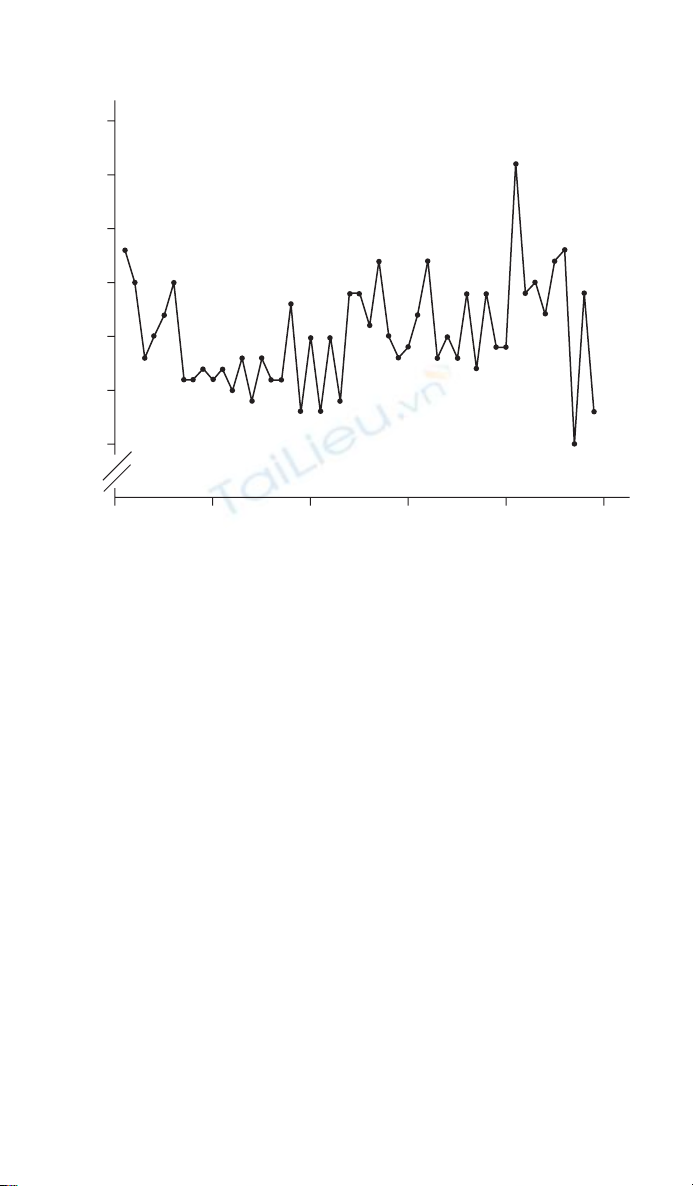

An example of a time series plot is given in Figure 8.1. The data are the

number of infant deaths per day in England and Wales over a 7-week period

during 1979.1 The important points to consider when drawing a time series

are that time should be on the X-axis (horizontal) and the series of events

that are being monitored, the observations, are on the Y-axis (vertical). In

addition, adjacent points should be joined by straight lines. If the origin has

been omitted this should be made clear, as here, by two diagonal lines on the

axis line. Care should be taken when examining published time series plots.

They are often used in newspapers and a common trick is not to show the

origin, so that a small trend can appear magnifi ed. This is discussed in more

detail in Section 2.3.

Time series plots and survival curves 91

8.3 Lowess smoothing plots

Lowess smoothing plots are a useful way of displaying some time series

data.2 They are described in more detail in Section 5.3, where they are

applied to continuous data. For time series they are useful for investigating

non-linear trends, as demonstrated here. Figure 8.2a shows the number of

prescriptions for non-selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), a type

of antidepressant, over a 3.5-year period, from 2002 to 2006 for one general

practice in Yorkshire, England (Senior J., Personal Communication, 2006).

The scatter plot seems to show a generally increasing trend, with more scatter

towards the end. However, fi tting a lowess smoothing curve with bandwidth

of 50% suggests that in fact the number of prescriptions peaked at around

month 30 (Figure 8.2b). This corresponds to the time when national guide-

lines were published by NICE recommending that SSRIs should be prescribed

in preference to non-SSRIs for the treatment of depression. The peak is sug-

gested by the data, and so lowess plots are useful for data exploration, but not

for testing hypotheses. Note that as the Y-axis does not begin at the origin

(value 0) this has been indicated by two parallel lines.

45

40

35

30

25

20

15

0102030

Time (days)

Infant deaths (n)

40 50

Figure 8.1 Daily infant deaths in England and Wales over a 7-week period during

1979.1

![Tổng quan về Physique: Giới thiệu chung [chuẩn nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2012/20120719/suthebeo/135x160/1214236_349.jpg)