MINIREVIEW

Physico-chemical characterization and synthesis of neuronally active

a-conotoxins

Marion L. Loughnan and Paul F. Alewood

Institute for Molecular Bioscience, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia

The high specificity of a-conotoxins for different neuronal

nicotinic acetylcholine receptors makes them important

probes for dissecting receptor subtype selectivity. New

sequences continue to expand the diversity and utility of

the pool of available a-conotoxins. Their identification

andcharacterizationdependonasuiteoftechniques

with increasing emphasis on mass spectrometry and micro-

scale chromatography, which have benefited from recent

advances in resolution and capability. Rigorous physico-

chemical analysis together with synthetic peptide chemistry

is a prerequisite for detailed conformational analysis and to

provide sufficient quantities of a-conotoxins for activity

assessment and structure–activity relationship studies.

Keywords:a-conotoxins; Conus; peptide synthesis; post-

translational modifications; sulfotyrosine.

Classification, primary structure and biology

of a-conotoxins

Cone snails are a group of hunting gastropods that

incapacitate their prey, which consists of worms, molluscs

or fish, by envenomation. Conotoxins from the venom of

cone snails are small disulfide-rich peptide toxins that act at

many voltage-gated and ligand-gated ion channels. They

can be grouped according to their molecular form into

several superfamilies, each defined by characteristic arrange-

ments of cysteine residues (not necessarily a single pattern),

and characteristic highly conserved precursor signal

sequence similarities. Individual conopeptide families

within a superfamily are denoted by Greek letters and

contain peptides that have a particular disulfide framework

and target homologous sites on a particular receptor [1].

Each of the characterized conopeptides is named using

a convention that indicates the activity (Greek letter), the

source species from which the peptide was first isolated

(Arabic letter(s)), the disulfide framework category (Roman

numeral) and the order of discovery within that category

(Arabic capital letter) [1]. For example a-AuIB belongs to

the a-conotoxin family and was the second peptide, B, with

that framework, I, isolated and reported from Conus aulicus

[1,2]. The names of some conotoxins deviate from this

nomenclature convention because their discovery preceded

its formulation. Hence some a-conotoxin names do not

conform to the alphabetical identifier system used to

indicate order of discovery of peptides with a specified

disulfide framework from the venom of any one species. The

framework identifiers I and II are both used in reference

to disulfide frameworks of the A superfamily without

distinction.

The A superfamily is so far comprised of the K

+

channel

blocking jA familiy and the aand aA families, which

together with the wfamily act at the nicotinic acetylcholine

receptor (nAChR). No aAorwconopeptides have been

reported to block neuronal nicotinic receptors with high

affinity. Rather, they are generally muscle-specific nicotinic

receptor antagonists [1]. The a-conotoxins fall into two

categories depending on whether they act at muscle-

type or neuronal-type receptors. The neuronally active

a-conotoxins are the focus of this minireview.

The known a-conotoxins consist of 12–19 amino acids.

Most a-conopeptides have four cysteine residues and the

general sequence GCCX

m

CX

n

C. The disulfide connectivity

is between alternate cysteine residues (I-III, II-IV).

The numbers of amino acid residues encompassed by the

second and third cysteine residues (m) and the third and

fourth cysteine residues (n) are the basis for a further

division into several structural subfamilies (a3/5, a4/3, a4/6

and a4/7) [1,3,4]. For example a4/6-AuIB belongs to the 4/6

disulfide loop size subgroup of the a-conotoxin family. The

neuronally active a-conotoxins are typically from the a4/7,

a4/6 and a4/3 subfamilies (Table 1). Peptides from the most

abundant a4/7subfamily are typically 16 residues in length

and range from 1600 to 1900 Da in mass. However

there have been recent additions to this subfamily in which

Correspondence to P. F. Alewood, Institute for Molecular Bioscience,

The University of Queensland, Brisbane, QLD 4072, Australia.

Fax: + 61 73346 2101, Tel.: + 61 73346 2982,

E-mail: P.Alewood@imb.uq.edu.au

Abbreviations:c-CRS, c-carboxylation recognition sequence;

nAChRs, nicotinic acetylcholine receptors; RT, retention time;

PTM, post-translational modification; TPST, tyrosyl-protein

sulfotransferase; TCEP, tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine; M-biotin,

maleimide-biotin; NEM, N-ethylmaleimide; IAM, iodoacetamide.

(Received 22 January 2004, revised 16 March 2004,

accepted 6 April 2004)

Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 2294–2304 (2004) FEBS 2004 doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04146.x

there have been extensions at the N-terminus or C-terminus

to a length of up to 19 residues and the mass range has been

extended to almost 2200 Da [5]. For example, there are

three additional residues at the N-terminus in the case of

GID [5]. Peptides from the a4/3 and a4/6 subfamilies are

typically 12 and 15 residues, respectively. Unusually, EI has

the same disulfide framework as a4/7 conotoxins that target

neuronal nAChRs but has been reported to antagonize the

neuromuscular receptor as do the a3/5 and aA conotoxins

[1,6].

There is a conserved proline between the second and third

cysteine residues in almost all a-conotoxins except ImIIA

and ImII [7,8]. However, the former has not been confirmed

to be a neuronally active a-conotoxin, despite its sequence

similarity with ImI and ImII. There is also a conserved

serine residue between the second and third cysteine residues

in many a-conotoxins. The residue N-terminal to the first

cysteine residue of the sequence is in most cases glycine,

although exceptions are the recently isolated peptides GID

and PIA that have c-carboxyglutamic acid and proline,

respectively, in that position (Table 1) [5,9]. More generally,

the residues in the first loop tend to fit into defined

categories, whereas the second loop seems to have greater

heterogeneity of residues. There appears to be a relationship

between selected sequence motifs and receptor subtype

specificity and these sequence patterns may be a basis for

further defining subclasses within the neuronally active

members of the a-conotoxin family [9a].

There are many interesting features of the biology of

Conus species and the functional applications of the

a-conotoxins in their venom. It has been conjectured that

of the estimated 500 Conus species, each appears to make at

least one nAChR antagonist [1]. However, for some Conus

species pharmacological screening of crude venom samples

has not shown a-conotoxin activity (A. Nicke &

M. Loughnan, unpublished results). Nonetheless it has

become apparent that in any one species there may be

multiple peptides that target nAChRs [1], and it seems likely

that the complement of neuronally acting a-conotoxins in

one species may cover a range of subtype specificities. There

are examples of combinations of muscle-type and neuronal-

type a-conotoxins in a single species, particularly in the case

of the fish-eating Conus species. For example, C. geographus

venom contains the muscle-acting a-conotoxins GI and

GII together with the neuronally acting a-conotoxins

GIC and GID [1,5,10] and C. magus venom contains the

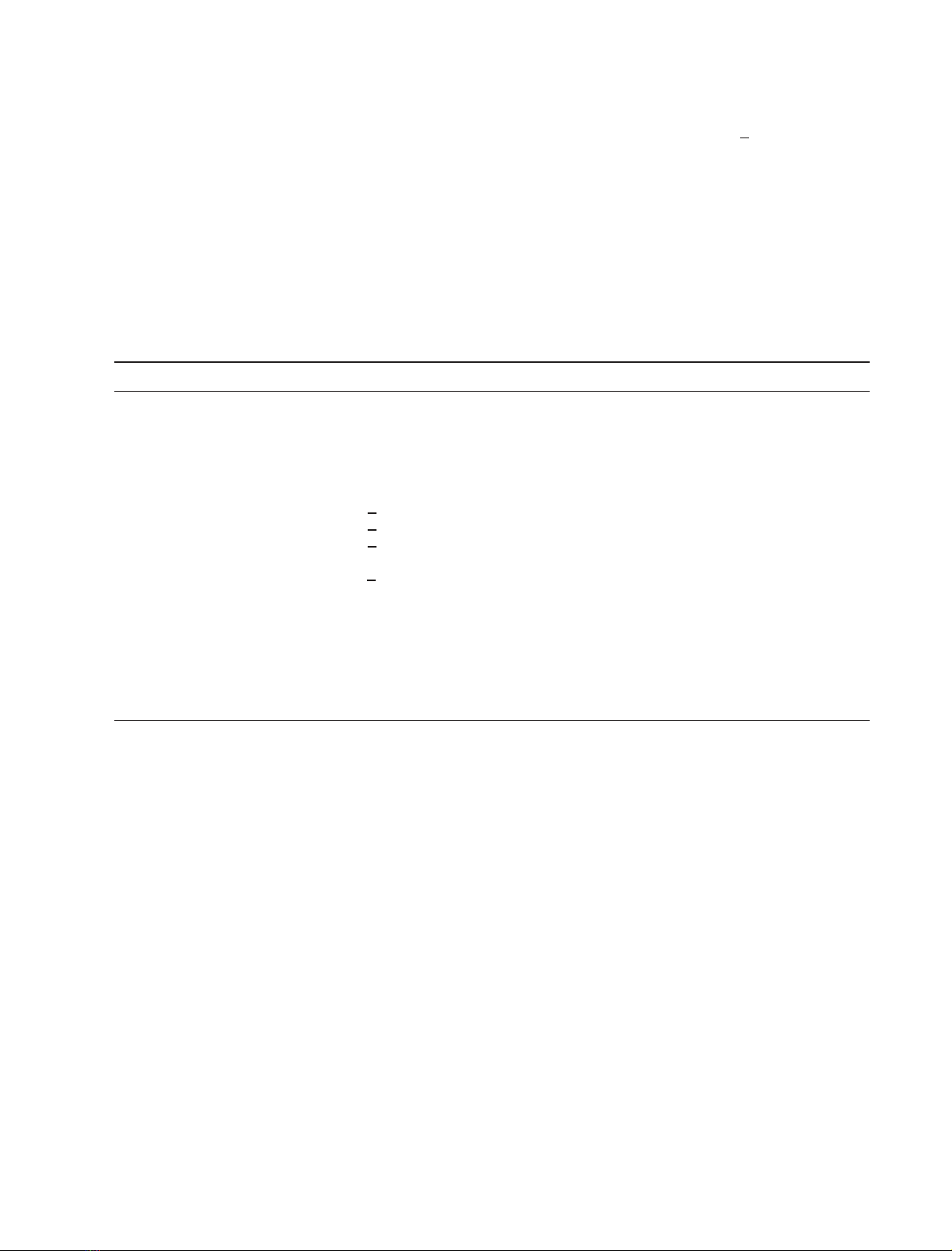

Table 1. Comparison of selected known a-conotoxins from a4/7, a4/6 and a4/3 families, their selectivity for mammalian nAChR subtypes, size, route of

discovery, method of synthesis and reference for synthesis. Asterisks (*) indicate an amidated C-terminus. The letters Oand Ydenote hydroxyproline

and sulfotyrosine, respectively. The letter Y

~~ denotes sulfotyrosine identified after original sequence was published. The symbol cdenotes

c-carboxyglutamic acid. Dashes indicate gaps in the sequence alignment. Mass (monoisotopic) in daltons, given for disulfide-bonded form.

Conserved cysteine residues are shown in red and a highly conserved proline in the first loop is shown in green. The peptides Vc1.1, GIC, ImII and

ImIIA were identified by prediction from the nucleic acid sequence. Other peptides were identified by isolation of the peptides from the venom ducts

in response to activity assays or by physico-chemical characteristics. Im peptides are from C. imperialis,AufromC. aulicus,MfromC. magus,Ep

from C. episcopatus,PnfromC. pennaceus,PfromC. purpurascens,GfromC. geographus and E from C. ermineus. Prey groups are denoted by p,

m, v for piscivores, molluscivores and vermivores, respectively. Discovery and synthesis methods were as follows: a, Discovered by peptide activity

at nAChRs in native tissues (e.g. bovine chromaffin cells, Aplysia neurons); b, Discovered by peptide activity at nAChRs heterologously expressed

in Xenopus oocytes; c, Discovered by peptide physico-chemical characteristics, and confirmed by synthesis and assay; d, Discovered by gene

sequencing with peptide sequence deduced from cDNA library obtained by RT-PCR of cone snail mRNA; e, Synthesised by Fmoc assembly,

trifluoroacetic acid cleavage and directed disulfide formation (off-resin); f, Synthesised by Fmoc assembly, modified trifluoroacetic acid cleavage

and air oxidation in ammonium bicarbonate for disulfide formation; g, Synthesised by tBoc assembly, HF cleavage and air oxidation in ammonium

bicarbonate for disulfide formation; N/A, not available.

Name Sequence Prey Selectivity Mass Methods Reference

ImI GCCSDPRCAWR----C*va7 1350.5 c,a,e [20]

ImIIA YCCHRGPCMVW----C*v N/A 1451.6 d [7]

ImII ACCSDRRCRWR----C*va7 1508.6 d,e [8]

AuIB GCCSYPPCFATNPD-C*ma3/b4 1571.6 b,e [2]

AuIA GCCSYPPCFATNSDYC*m (less active) 1724.6 b,e [2]

AuIC GCCSYPPCFATNSGYC*m (less active) 1666.6 b,e [2]

AnIA CCSHPACAANNQDYC*va3/b2, a7 1673.6 c,f [21]

AnIB GGCCSHPACAANNQDYC*va3/b2, a7 1787.6 a,f [21]

AnIC GGCCSHPACFASNPDYC*va3/b2, a7 1805.6 a,f [21]

MII GCCSNPVCHLEHSNLC*pa3b2; a6b2b3 1709.7 b,e [13]

EpI GCCSDPRCNMNNPDYC*ma3b2/a3b4; a7 1866.6 c,a,f [24]

Vc1.1 GCCSDPRCNYDHPEIC*ma3a7b4/a3a5b4 1805.7 d,a,g [22]

PnIA GCCSLPPCAANNPDY

~~

C*ma3b2

a

1701.6 a,g,e [58,51]

[A10L]PnIA GCCSLPPCALNNPDY

~~

C*a7

a

1663.7 g,e [60,51]

PnIB GCCSLPPCALSNPDY

~~

C*ma7

a

1716.6 a,g,e [59,51]

GIC GCCSHPACAGNNQHIC*pa3b2 1608.6 d,e [10]

GID IRDcCCSNPACRVNNOHVC#pa3b2 2184.6 b,g [5]

PIA RDPCCSNPVCTVHNPQIC*pa6b2b3 1980.8 d,e [9]

EI RDOCCYHPTCNMSNPQIC*p (muscle-type) 2091.8 a [6]

a

Synthesis method and activity refer to the unsulfated peptides.

FEBS 2004 Characterization and synthesis of a-conotoxins (Eur. J. Biochem. 271) 2295

muscle-acting a-conotoxin MI and the neuronally acting

a-conotoxin MII [11–13]. A biological interpretation of this

emerging pattern of paired ligand types is that prey capture

might rely on the combination of muscle-acting antagonists

to cause paralysis and neuronally acting antagonists to

inhibit the flight-or-fight response [10,14]. Although distinct

peptide complements have been attributed to individual

species [15], there are instances of a single a-conotoxin

sequence occurring in more than one species. For example,

GID from C. geographus has also been isolated from

C. tulipa venom [5].

Conus venoms together provide an array of ligands

with selectivity for various neuronal nAChR subtypes

(Table 1, [9a]). Evolutionarily, this diversity of toxins has

been generated by a hypermutation process that allows

protection of conserved cysteine residues and high substi-

tution rates for the intervening residues in the mature

toxin peptides [3,16,17]. Each venom peptide is processed

from a prepropeptide and the three defined regions of this

precursor (signal sequence, proregion, mature toxin) have

different rates of divergence [3,16]. Proposed diversifica-

tion mechanisms include gene duplication and subsequent

diversifying selection, or targeted gene mutation with

some sophisticated molecular regulation, perhaps based

on repair processes or recombination processes acting in

discrete exon regions [16–19]. Prey-driven diversifying

selection may be a factor for dominant expressed toxins,

given the feeding specificity of cone snail species [17]. It

has been suggested that nicotinic ligands from fish-hunters

are more likely than those from snail and worm-hunters

to target vertebrate nAChRs with high affinity [1]. Besides

the piscivores (fish-hunters) C. magus,C. geographus and

C. purpurascens, other species that have also yielded

neuronally active a-conotoxins include the vermivores

(worm-hunters) C. imperialis and C. anemone,andthe

molluscivores (mollusc-hunters) C. aulicus,C. victoriae,

C. pennaceus and C. episcopatus (Table 1) [2,5,7–10,13,20–

24]. Many more species are represented in a-conotoxin

sequence information contained in patent documents, for

example [25]. However these are not within the scope of

this review because their activities have not been reported,

although the patent applications reflect the commercial

interest in this class of conopeptides as potential candi-

dates for drug development.

Many of the neuronally active a-conotoxins show a

high conservation of the local backbone conformation

although the surfaces are unique [3,25a]. The common

structural scaffold suggests that the hypervariability of the

sidechain groups confers peptide specificity for different

neuronal nAChR subtypes [3]. Although the a-conotoxins

are considered to have rigid structures, multiple inter-

convertible isomers may exist in solution [1,3] (see also

below). This potential heterogeneity is an important issue

in the isolation, analysis and chemical synthesis of these

peptides.

Post-translational modifications of neuronally

active a-conotoxins

A feature of conotoxins in general is that they are relatively

richly endowed with a wide spectrum of post-translational

modifications (PTMs) and this aspect has been comprehen-

sively reviewed elsewhere [14,15,26]. The classical published

a-conotoxin sequences contained comparatively few mod-

ifications apart from disulfide bridges and C-terminal

amidation. However, more recently isolated peptides have

expanded the list of modifications and they now seem

comparable with the rest of the conotoxins in this respect

(Table 2). A thorough exploration of the significance of

these modifications for the function of a-conotoxins is yet to

be completed and reported.

Disulfide bridge formation is a basic feature of the

a-conotoxins with their defined cysteine spacing and

disulfide connectivity. Non-native disulfide-bonded cono-

peptides are often considered to be inactive but this is not

always the case. Intriguing results have been obtained in

structure-function studies of a synthetic variant of a-AuIB

with non-native disulfide bond connectivity, where an

enhancement of biological activity was observed [27].

Hydroxylation of proline has been observed in several

neuronally acting a-conotoxins but of these only GID has

been described [5]. Hydroxyproline also occurs elsewhere in

the A superfamily: in the muscle-specific a-EI, in aA-EIVA,

EIVB and PIVA and in w-PIIIE [1]. The significance of this

modification has not been determined. Many other cono-

toxins that contain multiple hydroxyproline residues also

have naturally occurring under-hydroxylated variants such

as in the example of TVIIA [28] and perhaps the modifi-

cation may not be critical. However there was no evidence

of a variant of GID with proline in place of the single

hydroxyproline residue [5].

Amidation of the C-terminus is a feature of most

conotoxins and so far occurs in the majority of the

a-conotoxins with the exceptions of GID and the muscle-

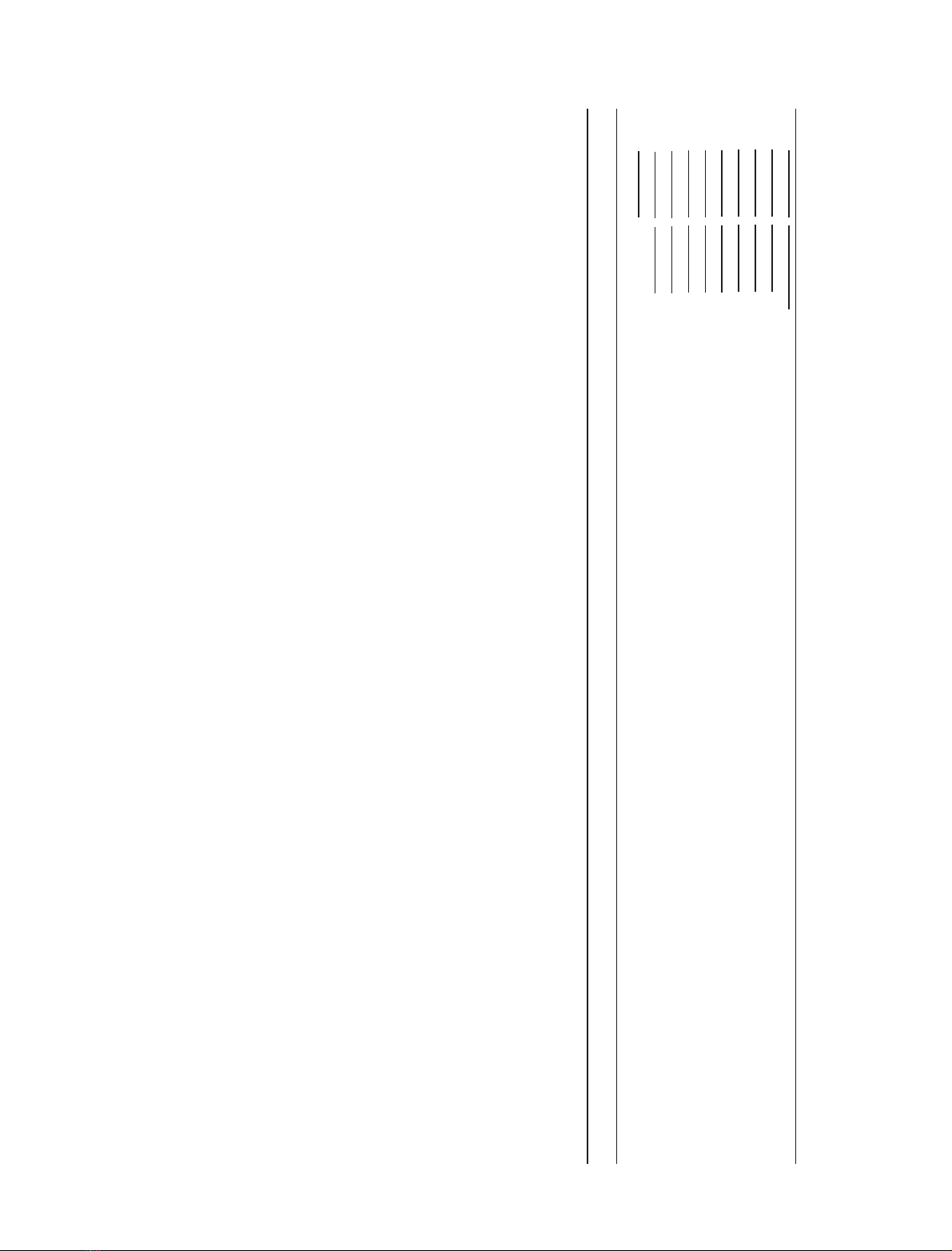

Table 2. Post-translational modifications (PTMs) in neuronal a-conotoxins.

PTMs in other conotoxins PTMS in a-conotoxins References

Disulfide bridge formation Yes all

Amidation of C-terminus Yes most (not in GID) [5]

Sulfation of tyrosine Yes EpI, PnIA, PnIB, AnIA, AnIB, AnIC [24,31,21]

Hydroxylation of proline Yes GID [5]

Carboxylation of glutamic acid Yes GID [5]

Cyclization of N-terminal Gln No

O-Glycosylation No

Bromination of tryptophan No

Isomerization of tryptophan No

Epimerization of other residues (L fiD) No

2296 M. L. Loughnan and P. F. Alewood (Eur. J. Biochem. 271)FEBS 2004

acting SII [1,5]. The functional significance of the nature of

the C-terminus in neuronal-type a-conotoxins has not been

established. However a recent study of the effects of an

amidated or free carboxyl C-terminus on activity of a

synthetic a-conotoxin (AnIB) at nAChR subtypes expressed

in oocytes showed subtype specific differences in activity [21].

Carboxylation of glutamic acid to c-carboxyglutamic

acid has been reported in GID [5]. It has been estimated that

10% of conopeptides contain c-carboxyglutamic acid and

the conantokins (NMDA receptor antagonists) have mul-

tiple c-carboxyglutamic acid residues that are important

for maintaining their three dimensional structure [15,29].

The existence of c-carboxylation recognition sequences

(c-CRSs) in conopeptide precursors from some Conus

species has been established and an enzyme responsible for

glutamic acid carboxylation in conantokin G has been

described [30]. The c-CRS regions in conantokin G and

bromosleeper peptides [30] are highly dissimilar suggesting

that thissequenceinformationcannotnecessarilybeextended

to other conopeptide families. c-CRSs in a-conotoxin

precursors have not been described.

Sulfation of tyrosine has been observed in EpI, PnIA,

PnIB, AnIA, AnIB and AnIC [21,24,31]. The mechanism of

sulfation of tyrosine by an enzyme, tyrosyl-protein sulfo-

transferase (TPST), has not been elucidated. It may involve

a recognition sequence in the peptide precursor [15] or a

consensus sequence in the mature peptide [32]. Alternat-

ively, secondary structure may be the major determinant of

sulfation and the TPST might broadly recognize any

sufficiently exposed tyrosine residue [33,34]. The sulfotyro-

sine-containing a-conotoxins have not previously been

reported to have substantially different activity from the

unmodified variants [15,24]. Recent comparisons of EpI

with [Y15]EpI, and AnIB with [Y16]AnIB found about

three-fold and ten-fold reduced activities, respectively, of the

unsulfated forms relative to the sulfated peptides [21,35]. In

the case of AnIB, tyrosine sulfation selectively influenced the

binding to the mammalian a7 but not the a3b2 subtype [21].

The effects of substitution of phosphotyrosine for sulpho-

tyrosine in a-conotoxins have not been investigated.

Post-translational modifications such as O-glycosylation

of serine or threonine residues, bromination of tryptophan,

isomerization of tryptophan or L fiD epimerization of

other residues have been observed in conotoxins from other

families [1,15] but not reported for a-conotoxins. However,

characterizations of a-conotoxins have not routinely inclu-

ded tests for isomerization and epimerization modifications.

Aspects of the biosynthesis of conotoxins in the cone snail

and the mechanisms for incorporation of PTMs have

garnered considerable interest [15]. Hypermutation of

amino acid residues is a feature of the mature toxins but

in contrast the prepropeptide precursor sequence, partic-

ularly the signal sequence, seems to be highly conserved for

each family of conotoxins [3,16]. Precursor sequences are

available for conotoxins from most families but there have

been relatively few precursors published in journals for the

a-conotoxins (Table 3). Nevertheless it is interesting to

examine the available prepropeptide sequence information

for ImIIA and Vc1.1, ImII, GIC and PIA, each of which

was identified by prediction from a genomic DNA clone

[7–10,22]. Comparison of the peptide sequences GID, EI,

ImIIA, GIC and PIA suggests that there are anomalies in

Table 3. Precursor sequence or cleavage site information for selected a-conotoxins. The mature peptide is underlined. The putative cleavage site for generation of the mature toxin from the prepropeptide at

one or more basic resisues is shown in bold.

Name Species Reference Sequence

GIC precursor C. geographus [10] SD GRNDAA--KA FDLI-SSTV- KKGCCSHPAC AGNNQHICGR RR

Vc1.1 precursor C. victoriae [22] MGMRMMFTVF LLVVLATTVV SSTSGRREFR GRNAAA--KA SDLV-SLTDK KRGCCSDPRC NYDHPEICG

ImIIA precursor C. imperialis [7] MGMRMMFTVF LLVVLATAVL PVTL-DRASD GRNAAANAKT PRLI-APFI- RDYCCHRGPC MVW----CG

ImII cleavage site C. imperialis [8]

a

RRACCSDRRC RWR----CG

ImI cleavage site C. imperialis [8]

a

RRGCCSDPRC AWR----CG

MII precursor C. magus [25] MFTVF LLVVLATTVV SFPS-DRASD GRNAAANDKA SDVITAL--- -KGCCSNPVC HLEHSNLCGR RR

AuIB precursor C. aulicus [25] MFTVF LLVVLATTVV SFTS-DRASD GRKDAA---- SGLI-ALTM- -KGCCSYPPC FATNPD-CGR RR

AuIA precursor C. aulicus [25] MFTVF LLVVLATTVV SFTS-DRASD GRKDAA---- SGLI-ALTI- -KGCCSYPPC FATNSDYCG

EpI precursor C. episcopatus [25] MFTVF LLVVLATTVV SFTS-DRASD SRKDAA---- SGLI-ALTI- -KGCCSDPRC NMNNPDYCG

PIA precursor C. purpurascens [9] SD GRDAAANDKA TDLI-ALTARRDPCCSNPVC TVHNPQICGR R

a

EMBL/Genbank/DDBJ databases accession numbers P50983, Q816R5.

FEBS 2004 Characterization and synthesis of a-conotoxins (Eur. J. Biochem. 271) 2297

relation to GID, EI and PIA, which each have an N-

terminal sequence motif RDX. It is tempting to speculate

about the relationship of this motif to the potential dibasic

cleavage sites for generation of the mature peptides from the

prepropeptides, particularly in those cases where the residue

at position X becomes post-translationally modified in the

mature peptide. However there are also many other

sequences reported in patent documents that have not been

considered here and for many of those the deduced cleavage

site does not have a dibasic motif [25]. There has been

increasing utility of molecular biology techniques for

identification of new a-conotoxin sequences. Reliance on

the gene sequence of a conopeptide alone without verifica-

tion from the peptide sequence might miss PTM sites, or

misidentify the cleavage site for generation of the mature

peptide. Much further work is necessary to elucidate the

mechanisms of incorporation of PTMs in the biosynthesis

of conopeptides. Appropriate methods of analysis need

to be addressed to ensure recognition of these PTMs,

if present, in the course of characterization of native

a-conotoxins.

Analysis of neuronally active a-conotoxins

using HPLC and MS, including identification

of post-translational modifications

Isolation and identification

Standard procedures for identification and isolation of

a-conotoxins generally incorporate separations using

reversed-phase HPLC, size exclusion or ion exchange

chromatography in combination with mass-based screening

and functional screening. Most of the a-conotoxins identi-

fied so far are relatively hydrophilic and hence tractable.

Mass-based screening entails searching by LC/MS or MS

alone for components with a mass in the defined range for

a-conotoxins and two disulfide bonds (identified by partial

reduction and alkylation studies and MS/MS). It may also

include diagnostic LC/MS for recognition of some post-

translational modifications and possibly MS/MS for recog-

nition of conserved sequence motifs. The small size range

of a-conotoxins would seem ideal for MS-based sequence

determination. However, complete de novo sequencing of

conopeptides by MS/MS is still considered experimental,

and primary sequence information is usually obtained by

Edman degradation sequencing, interpreted in conjunction

with MS data for the intact molecule. Efficient sequence

analysis usually requires that the peptides are reduced and

the cysteine residues alkylated in order to verify their

identification. Although there are standard procedures for

reduction and alkylation, their application to conopeptide

analysis and characterization is by no means trivial, and

often optimization on a case-by-case basis is required [14].

Sample amounts may be limiting even with the enhanced

sensitivity of current automated sequence analysis instru-

ments.

Chromatography and structural heterogeneity

Several a-conotoxins have a characteristic asymmetric peak

under standard reversed-phase HPLC elution conditions

[5,36]. The anomalous chromatographic behaviour is seen

particularly with a-CnIA, a-MI, a-GI and a-GID for both

native and synthetic forms and persists even after repeated

refractionation [5,36,37]. The asymmetry may be more

pronounced under isocratic elution conditions. It presum-

ably reflects structural heterogeneity and can be interpreted

as a slow interconversion between two conformers; this

conclusion has been supported by the results of structure

studies. NMR studies have shown the existence of two

distinct interconvertible conformers for GI and multiple

conformers of CnIA [36,37]. This heterogeneity may yet

prove to be an important feature of some a-conotoxins in

the understanding of structure-function relationships and

the interaction of these ligands with the nAChR.

Identification of PTMs

Methods for the characterization of PTMs in conotoxins

have been reviewed elsewhere, with particular emphasis

on the utility of MS [14], but specific aspects relevant to

a-conotoxins (identification of C-terminal amidation,

sulfotyrosine, hydroxyproline and c-carboxyglutamic acid)

are revisited here. The identification of the PTM is usually

confirmed by synthesis of the modified a-conotoxin and

comparison with the natural peptide.

Identification of the nature of the C-terminus. The

identification of C-terminal amidation or a free carboxyl

terminus in an a-conotoxin is usually straightforward with

the one mass unit difference between the two forms readily

apparent from the monoisotopic mass determined by high

resolution mass spectrometry. There may be difficulties in

interpretation of MS data when there are ambiguities

arising from, for example, asparagine to aspartic acid, or

glutamine to glutamic acid changes [14]. The a-conotoxins

EpI, PnIA, GIC, GID, AnIA and AnIB contain pairs of

asparagine residues [5,10,21,23,24] (Table 1), and deamida-

tion may confound MS data for these peptides.

Determination of sulfotyrosine. Identification of sulfo-

tyrosine in peptides is usually by mass spectrometry and

the lability of the sulfogroup in mass spectrometry

analysis allows recognition of the modification, and

differentiation of sulfotyrosine and phosphotyrosine [38].

Characterization of the sulfotyrosine-containing a-cono-

toxin EpI was undertaken by a combination of mass

spectrometry and modified amino acid analysis [24]. The

conotoxins a-PnIA and a-PnIB from C. pennaceus were

initially identified and reported as unmodified sequences

although an unidentified mass discrepancy had been

recognized [23]. The verification of tyrosine sulfation in

a-PnIA and a-PnIB and revision of those sequences were

made in an investigation of labile sulfo- and phospho-

peptides by electrospray MALDI and atmospheric

pressure MALDI mass spectrometry [31]. The sulfation

of three conotoxins from C. anemone was identified on

the basis of LC/MS under different conditions together

with the difference between the observed mass and that

predicted from primary Edman sequence data [21].

The presence of either sulfation or phosphorylation may

be indicated when liquid chromatography/electrospray

ionization mass spectrometry shows doubly protonated

species of the modified a-conotoxins with additional related

2298 M. L. Loughnan and P. F. Alewood (Eur. J. Biochem. 271)FEBS 2004