22 CHAPTER 1 ■ DEVELOPMENT BEST PRACTICES

Report Pagination Style

Different report pagination styles will affect the performance in displaying the report. For

example, some of the pagination styles will display something like “Row Ranges X to Y of Z,”

If you do not need to display how many total rows are returned from the query, you should

choose to use a pagination style that displays only “Row Ranges X to Y.”

Error and Exception Handling

Your APEX application can use many different anonymous PL/SQL blocks, functions, proce-

dures, and packages when it is executing. If an error or exception occurs during the execution

of some code, you need to be able to handle that error or exception gracefully, in such a fashion

that flow of execution by the APEX engine is not broken. For example, the following code

catches the exception and sets the value of an application item:

declare

v_salary INTEGER;

begin

select

salary

into

v_salary

from

emp

where

empno = :P1_EMPNO;

return v_salary;

:APP_ERROR_MSG := null;

exception

when no_data_found then

:APP_ERROR_MSG := 'Could not find the employee record.';

end;

You can then display the application item on the page in an HTML region using this

syntax:

&APP_ERROR_MSG.

You would then create a branch on the page to branch back to itself if the value of the

application item is not null, thereby enabling the user to see the error and correct it.

Packaged Code

APEX allows you to write SQL and PL/SQL code directly in a number of places via the Applica-

tion Builder interface. For example, suppose you create the following after-submit process in

your login page to audit that a user logged in to the application.

CHAPTER 1 ■ DEVELOPMENT BEST PRACTICES 23

begin

insert into tbl_audit

(id, user_name, action)

values

(seq_audit.nextval, :APP_USER, 'Logged On');

end;

Now, while this would work, it also means that if you ever want to modify the logic of the

auditing, you need to change the application. For example, notice that you aren’t currently

storing a timestamp of when the audit action was performed. To add that functionality, you

would need to modify the tbl_audit table and add an extra column to store the timestamp

information (if that column did not already exist), and then edit the application to change the

PL/SQL page process to include the timestamp information, like this:

begin

insert into tbl_audit

(id, ts, user_name, action)

values

(seq_audit.nextval, sysdate, :APP_USER, 'Logged On');

end;

So, potentially for a very simple change, you might need to modify the application in

development, export a new version of the application, import that version into a test environ-

ment, and so on through to production.

A much more efficient way is to try to isolate the number of places you directly code logic

into your application by placing that code into a package, and then calling the packaged pro-

cedure or function from your application. For example, you could change the PL/SQL page

process to simply do this:

begin

pkg_audit.audit_action('Logged On');

end;

This allows you to encapsulate all of the logic in the packaged code. Assuming you are not

making fundamental changes to the package signature, you can modify the internal logic with-

out needing to change the application. This design would allow you to change the table that the

audit information is stored in or to add new columns and reference session state items without

needing to change anything in the application itself. All you would need to do is recompile the

new package body in the development, test, or production environment. This would result in

much less downtime for the application, since you no longer must remove the old version of

the application and import the new version. Using this method really does allow downtimes of

just a few seconds (the time it takes to recompile the package body), as opposed to minutes, or

potentially hours, while new versions of the applications are migrated.

Obviously, you won’t always be able to completely encapsulate your logic in packages.

And sometimes, even if you do encapsulate the logic, you may need to change something in the

application (for example, to pass a new parameter to the packaged code). However, it is good

practice to use packaged logic where you can. Using packaged code can save you a lot of time

later on, as well as encourage you to reuse code, rather than potentially duplicating code in a

number of places throughout your application.

24 CHAPTER 1 ■ DEVELOPMENT BEST PRACTICES

Summary

This chapter covered some best practices for using APEX. You don’t need to follow our advice.

Many people just charge in and begin coding without thinking to lay a solid foundation for

their work. Some of what we advocate in this chapter may actually slow you down at first, but

it will save you time in the long run. Helping you to work more efficiently, and taking a long-

term view of doing that, is one of the reasons we’ve written this book.

25

■ ■ ■

CHAPTER 2

Migrating to APEX from Desktop

Systems

Many organizations come to rely on systems that have been built using desktop applications

such as Microsoft Excel, Access, and similar tools. For example, employees might store their

own timekeeping data in an Excel spreadsheet, which is sent to the payroll department each

month, or the sales department might keep all its customer details in an Access database.

These applications often begin as simple data-entry systems, but evolve over time as more

functionality is added or the business rules regarding the data change. Using desktop-based

systems to manage data has a number of drawbacks, such as the following:

• Each person who wants to work with the data needs to install the client software (for

example, Excel) on his machine.

• Data cannot be easily shared with other applications.

• In the case of Excel, only one person can be in control of the data at once.

• It is difficult to manage the changes made by people working with their own copy of the

data.

• The data might not be backed up as part of any regular backup procedures.

• It can be difficult to establish and restrict exactly who has access to the data.

• There is no fine-grained control over what data a user is allowed to view and modify.

• Confidential data can be taken off-site by a user, via an e-mail attachment or by copying

a spreadsheet onto a USB key, for example.

By using APEX, you can avoid many of these issues. Users won’t need to install any dedi-

cated client software, because all they will need to use your APEX application is a supported

browser. You can store the data centrally within the Oracle database, which enables it to be

backed up as part of your regular database backup policy (for example, if you perform database

backups using RMAN, the application data will also be backed up).

You can also use features such as Fine-Grained Access Control (FGAC) to control the data

users are allowed to access. When you combine this with auditing, you will not only be able to

control exactly what data users can access, but you will also have an audit trail of what data

they did access.

26 CHAPTER 2 ■ MIGRATING TO APEX FROM DESKTOP SYSTEMS

We want to stress that APEX is capable of far more than just being an Excel or Access

replacement. You really are limited only by your imagination in the applications that you can

create. However, many existing Excel and Access systems could benefit from being replaced by

APEX applications, so it can be a great place to begin learning how to take advantage of this

powerful and rapid development tool.

Excel Migration

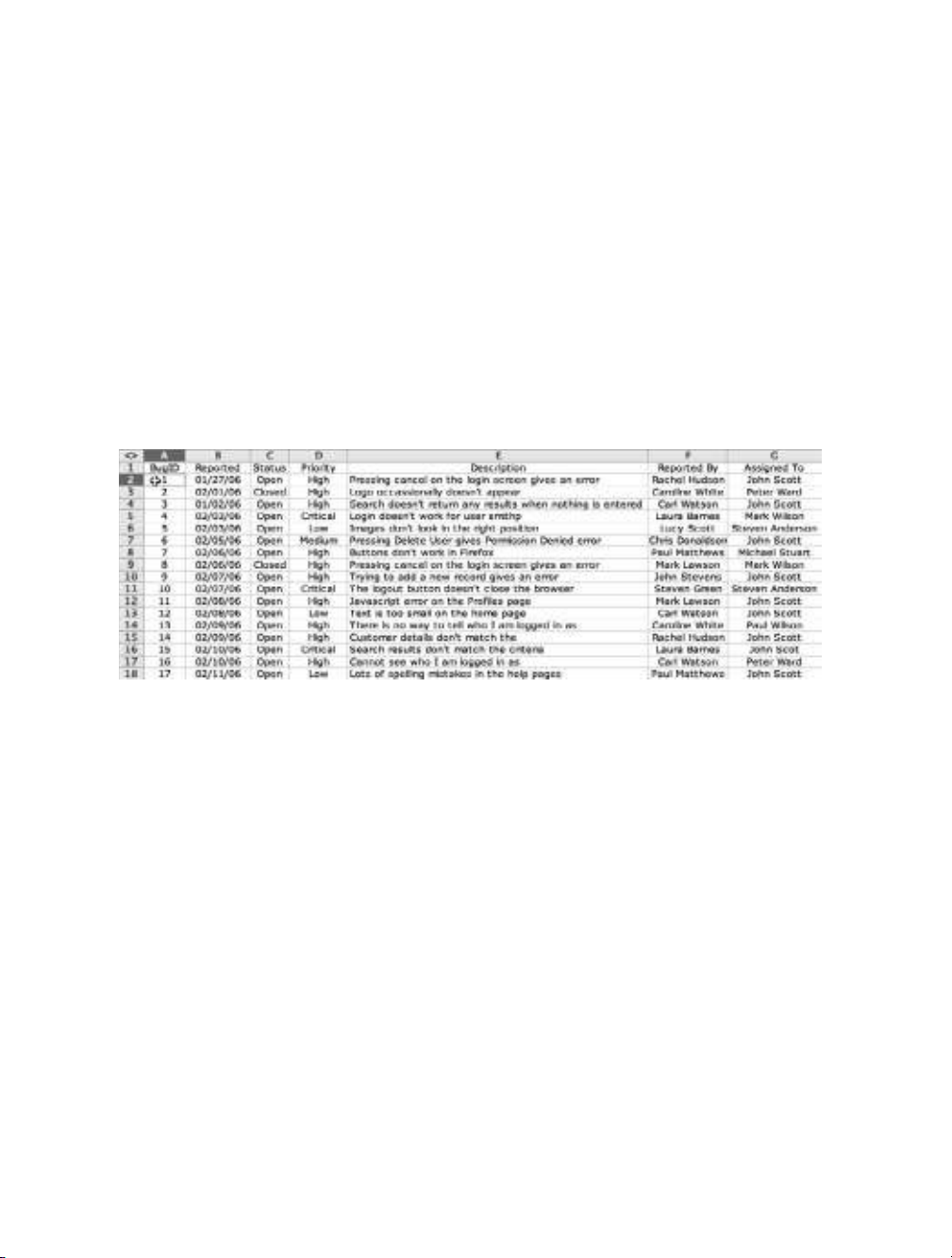

In this section, we will demonstrate how you can take an existing Excel spreadsheet and

convert it into an APEX application. The sample spreadsheet, shown in Figure 2-1, is used

to document the status of bugs that have been reported in another application. Each bug is

assigned to a developer, and the status of the bug is changed from open to closed when that

bug has been fixed.

Figure 2-1. Bug report spreadsheet

The existing spreadsheet solution suffers from many of the drawbacks mentioned at the

beginning of this chapter, particularly the fact that only one person at a time can be in control

of changing the spreadsheet. Typically in this sort of scenario, one person is tasked with main-

taining the spreadsheet, and might receive the bug reports from the testing team via e-mail.

When a bug report e-mail message is received, the person in charge of maintaining the spread-

sheet adds the bug to the list and looks for a developer to assign the bug to, usually based on

who has the least number of open bugs (which is far from an ideal way to measure how busy

the developers are!). The spreadsheet maintainer might send weekly or monthly updates to let

people know the status of the bugs at that point in time.

Clearly, this sort of system could be improved by removing the potential bottleneck of the

spreadsheet maintainer needing to collate all of the data. If the testing team members were

allowed to enter new bugs directly into the system themselves, the bugs would appear in the

report immediately. Also, if the developers could select which bugs to work on, rather than

having bugs assigned to them, they would likely pick ones related to the areas of the system

they know well.