Copyright © IFAC

12th

Triennial World Congress.

Sydney. Australia. 1993

AUTOMATIC

TUNING OF

DECENTRALIZED

PID

CONTROLLERS

FOR TITO

PROCESSES

Z .

.I.

Paltnor,

Y.

Halcvi

and

N.

Krasncy

Fuculty

of

Mccizani"al

En}!.in('('fin}!..

T('cizllion . I/aifel 3200(]. Israel

Abstract

The

paper presents a new automatic tuning algorithm for Decentralized PID Control

for

two

inputs -

two

outputs (TITO) plants.

The

tuning procedure. which is an extension

of

the

Ziegler-Nichols method requires identification

of

a critical point consisting

of

critical gains

of

the various loops and a critical frequency. Unlike

SISO

plants there are infinitely many such

points and

knowledge

of

the desired one is essential to the tuning procedure.

The

auto-tuner

identifies

the

desired

critical point with no apriori information

of

the process. During the

identifiction phase all controllers are replaced by relays. thus generating limit

cycles

with the

same

period in both loops. It

is

shown that this limit cycle corresponds to a single critical point

of

the process. By varying the relays parameters different critical point can be determined.

The

auto-tuner

contains

a

procedure

which

converges

rapidly to the desired critical point while

maintaining the amplitudes

of

the process variables within prespecified ranges.

The

steady-state

process

gains. which are required for the appropriate

choice

of

the desired critical point, are

determined in closed-loop fashion simultaneously with the identification

of

the critical points. It

is shown that the proposed auto-tuner

is

more efficient and reliable than a recently published

algorithm

and

works

well also

in

cases

where the laller algorithm fails to

converge

and even

destabilizes the system.

Keywords: Decentralized Control; Automatic Tuning; Interactions;

PlO

Control.

I.

INTRODUCTION

Decentralized

PlO

control is

one

of

the most

common

control

schemes

for interacting multiple-input multiple-output (M1MO)

plants in the

chemical

and process industries.

The

main reason

for

this is its

relatively

simple

structure

which is

easy

to

understand and

to

implement.

The

number

of

tuning parameters

IS

3n where n

IS

the

number

of

inputs and outputs while in full

matrix

PlO

control

there

are 3n2

parameters.

Even

for

moderate

size

systems

this is a significant reduction.

In

case

of

actuator

or

sensor

failure,it

is

relatively

easy

to

stabilize

manually

be~ause

only

one

loop is directly affected by the

faIlure.

Desplle

llS

Simple structure. decentralized PID control

has a long record

of

satisfactory perfonnance.

We

turn

now

to the

problem

of

tuning these controllers. It is

assumed

throughout

this

paper

that an analytic model

of

the

process

is not available and the tuning procedure is based on

expenmental

data. Even for single-input single-output (SISO)

systems

the tuning

of

a

PlO

controller is not an easy task.

The

most

common

design procedure is the Ziegler-Nichols method

(Zlegler

and

Nlchols,

1942).

The

fundamental

step

in that

method

is the

identification

of

the critical gain and critical

frequency

of

the plant. that together are called the critical point.

Based

on

these values, the controller gain and the integral and

derivative

coefficients

are calculated.

In

MIMO

svstem

the

tuning

problem

is

many

times

more

complicated

due

to the

interactions

between

loops. A

change

of

a single

parameter

affects. in

general,

all

other

loops as well in a way which is

hard to predict.

Only

a limited number

of

works addressed the

tuning

of

decentralized

PID controllers. Marino-Gallarraga

et

al.

(1987)

presented

a

design

method

which

combines

information

regarding

the

MIMO

system

performance

and

SISO

properties

of

each

loop.

The

method

in

(Niederlinski,

1971) is a

more

natural extension

of

the Ziegler-Nichols tuning

procedure

to the

MIMO

case

.

It

is based on

replacing

the

controllers

by

gains

and

identification

of

a

critical

point

~onsisting

of

n scalar critical gains and the critical frequency.

rhe

main

departure

fomlthe

SISO

case is that

MIMO

systems

lave

infinitely

many

critical points.

The

collection

of

these

'oims

define

a hypersurface in the gains space which is called

he

stability

limits.

Consequently

one

has to

prespecify

the

lesired

critical

point,

e.g.

equal

loop

gains.

Once

the

.Jarameters

of

the critical point are detcmlined the controllers are

tuned in a similar fashion to the classical Ziegler-Nichols rules.

The

direct application

of

the Ziegler-Nichols mcthod has

some

shortcomings.

The

procedure

involves

trial

and

error

experiments

to

identify

the

critical

point.

During

these

experiments

the system might be unstable for a period

of

time.

which is risky. When the critical point

is

identified. there

is

no

control

over

the

amplitude

of

oscillations

of

the

process

73

·

nriablt:.

In

addition the

procedure

requires

an

experienced

operator

and is time consuming.

The

same problems exist for

thc

MIMO

case

and

are

even

more

severe.

Astriim

and

Ilagglund

(1984 and 1988) suggested the use

of

a relay in the

identification phase for a

SISO

system. Instead

of

a system on

the verge

of

instability the critical point is identified from a

stable limit cycle.

This

is also very convenient for auto-tuning

where by selling a tuning mode the

PlO

controller is replaced

by a relay, the critical point is identified and the parameters are

updated.

(Zgorzelski

. 1988) and

(Zgorzelski

et

aI., 1990)

extended

that idea to the

MIMO

case.

In

their approach

one

controller

is

replaced

by

a

relay

while

the

others

by

P

controllers

whose

values

are

adjusted

in

each

of

the

experiments until the desired critical point

is

obtained.

In

this

paper

we suggest a new algorithm for auto-tuning

of

decentralized

PlO

controllers for two-input two-output (TITO)

systems.

The

main departure from the method

of

(Zgorzelski et

aI., 1990)

is

that the controllers

in

all the loops are replaced by

relays. Each

such

experiment

identifies a critical point. By

varying the magnlludes

of

the relays the identified critical point

moves

along

the stability limits.

The

algorithm

changes

the

magnuudes

of

the relays such that convergence to the desired

critical point is obtained within a small number

of

experiments.

Funhermore,

the steady state gains needed for the definition

of

the critical point, are identified simultaneously with the critical

gains and frequency and

do

not require a separate experiment.

The

material

is

organized

as follows:

In

section 2 a

short

review

of

the auto-llIncr for

SISO

system is given. Section 3

discusses

the

manual

lUning procedure for

TITO

system

and

sec lIon 4 describes the

suggested

auto-tuner.

The

results are

summarized and discussed in section

5.

2.

AUTO-TUNING

OF

PID

CONTROLLER

FOR

SISO

SYSTEMS

We start by a

shon

review

of

the auto-tuner for

SISO

systems.

The

problem

is

as

follows:

Given

a

stable

but

otherwise

unknown plant pes) find a selling

of

the PID controller

C(s) =

K(!

+

R/s

+ Os)

(2.1)

that gives satisfactory performance. (In practice the derivative

part contains a filter with a time constant which is proportional

to 0 but

much

smaller).

The

most

common

and

useful

approach to the problem is the Ziegler-Nichols (1942) design

method.

The

first step in this

method

is to

replace

the

PID

controller by a proportional controller and gradually increase its

gain until the

system

reaches

a state

of

neutral stability. i.e.

oscillation with constant amplitude. The gain which achieves

that is called the critical gain

Kcr

and the frequency

of

oscillations, which is calculated from their time period,

is

called

the critical frequency w

cr

. The parameters

K,

Rand

Dare

then given as

K = aKcr. D =

y/w

cr

(2.2)

where

a,

~

and y are

constants

and there are several

suggestions for their exact values. [f a Nyquist plot

of

the plant

is available then

Kcr

and

W<~

can be calculated out

of

it.

At W

=

Wcr

the plot crosses the negative real axis and the intersection

point is -I/Kcr.

The above mentioned experimental procedure for detennining

Kcr

and

W<~

has some shortcomings. During the trial and error

phase the gain might be set too high thus giving rise to a

temporary state

of

instability which is risky. Even

if

this is

avoided

there is no control

over

the

amplitude

of

the

oscillation.

That

may lead to unacceptable response

or

to

distortion

of

the signals, thus also incorrect critical gain and

frequency, due to saturation.

To

circumvent those difficulties

it

was suggested (Astrom and Hagglund,

19B4

and 198B) to

use relays

in

the identification process and to calculate

Kcr

and

Wcr from the stable limit cycles that are reached. Under the

standard

assumptions

of

the

describing

function

Kcr

is

calculated from

4M

Kcr=-

na (2.3)

where M and a are the relay and the limit cycle amplitudes

respectively. w cr is calculated as before from the time period

of

the response. [n addition to the superior robustness

of

this

procedure, the amplitude a can be adjusted

by

appropriate

selection

of

M. [n case

of

noisy measurement the ideal relays

may be replaced

by

a relay with hysteresis.

[n

such cases there

is a trade-of between the insensitivity to noise, which requires

larger hysteresis and the accuracy

of

the fonnula for Kcr that

corresponds to zero hysteresis.

An advantage

of

the relay-based method is that it is suitable for

auto-tuning. When the auto-tuner is set to the tuning mode the

controller is replaced

by

a relay and the experiment begins. The

limit

cycle

time period is

detennined

by

measuring

time

between zero crossings and its amplitude from peak to peak

values.

These

values are then used to update the controller

parameters.

3.

TUNING

PROCEDURE

FOR

TITO

SYSTEMS

Stability Limits

ofT/TO

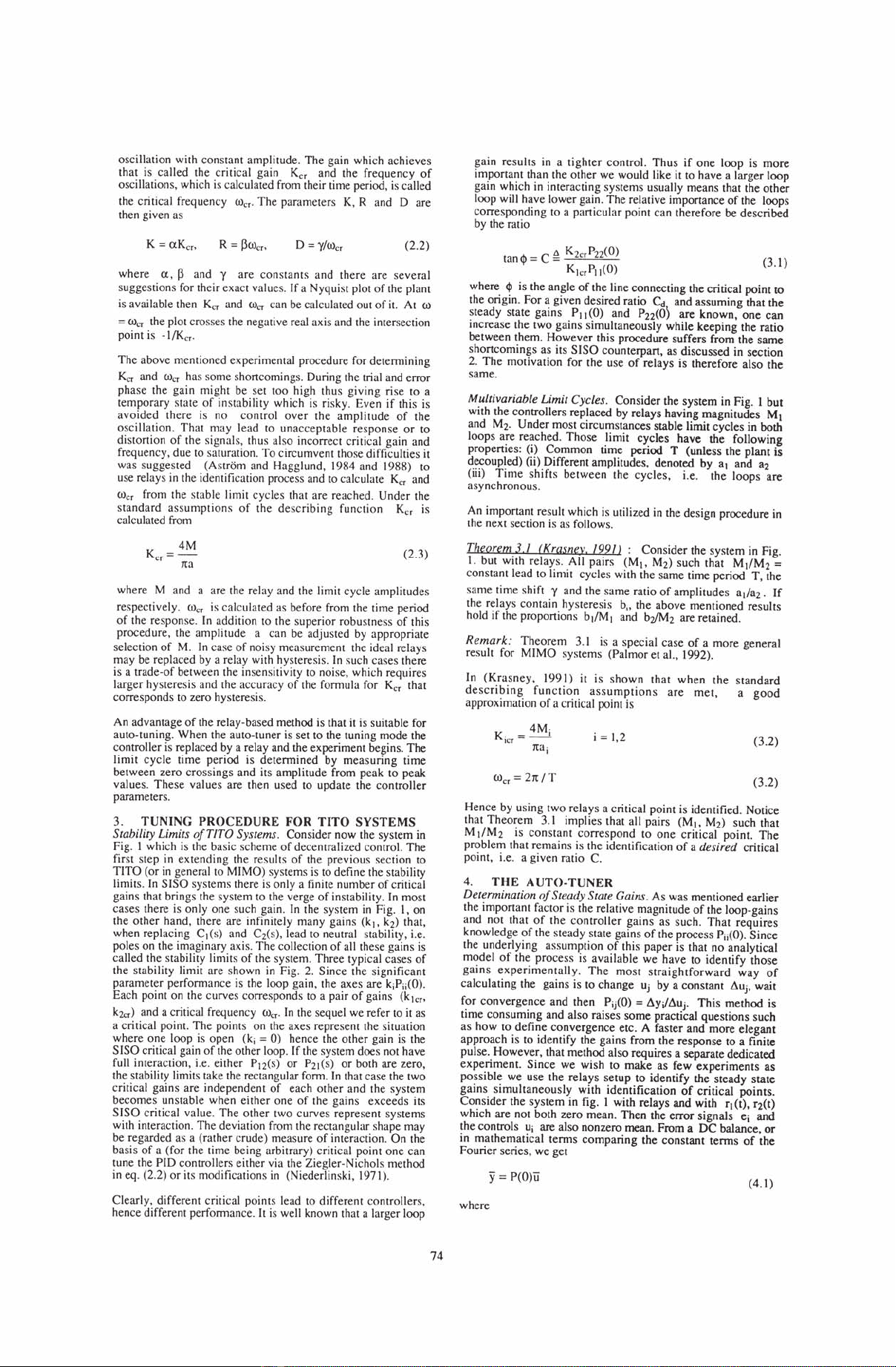

Systems. Consider now the system in

Fig. I which is the basic scheme

of

decentralized control. The

first step in extending the results

of

the previous section to

T[TO (or

in

general to MIMO) systems

is

to

define the stability

limits.

[n

S[SO systems there is only a finite number

of

critical

gains that brings the system to the verge

of

instability. [n most

cases there is only one such gain. [n the system

in

Fig. I, on

the

other

hand, there are infinitely many gains (k l, k2) that,

when replacing Cl (s) and C2

(S),

lead to neutral stability, i.e.

poles on the imaginary axis. The collection

of

all these gains is

called the stability limits

of

the system. Three typical cases

of

the stability limit are shown

in

Fig. 2. Since the significant

parameter perfonnance is the loop gain, the axes are kjPjj(O).

Each point on the curves corresponds to a pair

of

gains

(k

1cr

,

k2cr)

and a critical frequency w

cr

.

[n

the sequel we refer

to

it

as

a critical point. The points on the axes represent the situation

where one loop is open (ki = 0) hence the

other

gain is the

S[SO critical gain

of

the other loop. [f the system does not have

full interaction, i.e. either P

12

(s)

or

P21(S)

or

both are zero,

the stability limits take the rectangular fonn.

[n

that case the two

critical gains are independent

of

each

other

and the system

becomes unstable when either one

of

the gains exceeds its

S[SO critical value.

The

other two curves represent systems

with interaction. The deviation from the rectangular shape may

be regarded as a (rather crude) measure

of

interaction.

On

the

basis

of

a (for the time being arbitrary) critical point one can

tune the P[D controllers either via the Ziegler-Nichols method

in eq. (2.2) or its modifications

in

(Niederlinski, 1971).

Clearly, different critical points lead to different controllers,

hence different perfonnance. lt is well known that a larger loop

74

gain results

in

a tighter control.

Thus

if

one

loop is

more

important than the other we would like

it

to have a larger loop

gain which in interacting systems usually means that the

other

loop will have lower gain. The relative importance

of

the loops

corresponding to a particular point can therefore be described

by

the ratio

(3.1 )

where

q,

is the angle

of

the line connecting the critical point to

the origin.

For

a given desired ratio

Cd

and assuming that the

steady state gains P11(0) and P

22

(O)

are known,

one

can

increase the two gains simultaneously while keeping the ratio

between them. However this procedure suffers from the same

shortcomings as its SISO counterpart, as discussed in section

2.

The

motivation for the use

of

relays is therefore also the

same.

Multivariable Limit Cycles. Consider the system in Fig. I but

with the controllers replaced by relays having magnitudes Mt

and

M2.

Under most circumstances stable limit cycles in both

loops are reached. Those limit cycles have the following

properties: (i)

Common

time period T (unless the plant is

decoupled) (ii) Different amplitudes, denoted by al and

a2

(iii)

Time

shifts

between

the cycles, i.e. the loops are

asynchronous.

An important result which is utilized

in

the design procedure

in

the next section is as follows.

Theorem 1 1 (Krasne}',

19911:

Consider the system in Fig.

\.

but with relays. All pairs

(M(.

M2) such that Mt

/M2

=

constant lead to limit cycles with the same time period T, the

same time shift y and the same ratio

of

amplitudes

ada2.

If

the relays contain hysteresis b" the above mentioned results

hold

if

the proportions bt/M t and

b2fM2

are retained.

Remark:

Theorem

3.1

is a special case

of

a

more

general

result for

M[MO

systems (Palmor et aI., 1992).

In

(Krasney,

1991) it is

shown

that when the

standard

describing

function

assumptions

are

met,

a

good

approximation

of

a critical point is

4M

Kicr =

--'

nai

wcr=2nlT

i = 1,2 (3.2)

(3.2)

Hence by using two relays a critical point is identified. Notice

that

Theorem

3.1

implies that all pairs (M

I,

M2) such that

M

t/M2

is

constant

correspond

to

one

critical point.

The

problem that remains is the identification

of

a desired critical

point, i.e. a given ratio C.

4.

THE

AUTO-TUNER

Determination

of

Steady State Gains. As was mentioned earlier

the important factor is the relative magnitude

of

the loop-gains

and not that

of

the

controller

gains as such.

That

requires

knowledge

of

the steady state gains

of

the process

Pji(O)

. Since

the underlying assumption

of

this paper is that no analytical

model

of

the process is available we have to identify those

gains

experimentally.

The

most

straightforward

way

of

calculating the gains is to change

Uj

by a constant t.Uj, wait

for

convergence

and then

Pij(O)

= t.yJt.Uj.

This

method

is

time consuming and also raises some practical questions such

as how to define convergence etc. A faster

and

more elegant

approach is to identify the gains from the response to a finite

pulse. However, that method also requires a separate dedicated

experiment. Since we wish to make

as

few

experiments

as

possible we use the relays setup

to

identify the steady state

gains

simultaneously

with identification

of

critical

points.

Consider

the system

in

fig. I with relays and with rt (t), r2(t)

which are not both zero mean. Then the error signals ei and

the controls

Uj

are also nonzero mean. From a

DC

balance,

or

in mathematical

tenns

comparing

the constant

terms

of

the

Fourier series, we get

y=

P(O)u

(4.1 )

where

If

-YI(I)dt

T

()

If

-uI(t)dt

T

()

y=

u=

If

-Y2(t)dt

T

()

If

-u2(t)dt

T

()

Repeating

the

experiment

twice,

with

different

references

signals

we

get

(4.2)

where the

superscripts

denote

the

experiment

number.

If

the

reference

signals

are

selected

appropriately,

e.g.

ri(t)

= 0,

d(I)"#

0

and

r?(I)"# 0,

ri(I)

= 0, then the matrix

that

multiplies

PtO) is

nonsingular

and

the 2 x 2

system

can

be

easily

solved.

IdenrificQlion

of

a

Desired

Critical Point

..

So

far

we

have

shown that an

experiment

with two relays

determines

a critical

point

and

that

after

two

experiments

the

steady

state

gains

are

known. By

changing

the relays

magnitudes

M1,

M2

the critial

point that is identified

moves

along

the stability limits

of

the

system.

From

Theorem

3.1 it follows that the

critical

point

depends

only

on

the

ratio

MI/M2.

Though

theoretically

the

results

are

independent

of

the

absolute

magnitudes

M I

and

Ml,

those

values

do

have

practical significance.

To

reduce

the

effect

of

noise

one

needs

a certain

amount

of

hysteresis

and

to

keep

the identified point

close

to its real values the hysteresis

should

be

small

with

respect

to M,

hence

there is a

lower

bound

on M.

On

the

other

hand

too

large M's

cannot

be used

either

as a result

of

saturation

or

because the allowed

change

in

y is

restricted.

Theorem

3.1 thus

give

another

degree

of

freedom in the experiments.

Substituting

Kicr

from

eq. (3.2) into eg. (3.1) we

obtain

that

in the desired critical point

~=~~P22(O)

M2 Cd

a2

PII(O)

recalling that from

Theorem

3.1

(4.

3)

(4.4)

via

some

unknown

implicit

function f, the

problem

becomes

that

of

finding MJlM2 such that (4.3) holds.

In

other

words,

MI!M2 that

leads

to the desired angle

ci>d-

This

is achieved by a

series

of

experiments

that will

hopefully

converge

to the

right

value

.

The

procedure

consists

of

two

parts:

The

first

two

experiments

which

serve

as an initial guess

and

the rest

of

the

experiments

where the ratios are selected judiciously.

Notice

that the

calculation

of

<I>

requires

knowledge

of

the

steady

state

gains

PII

(0)

and P12(0).

As

explained

earlier

those

gains

are

obtained

after

two

experiments

so

until the

second

experiment

is

completed

we

do

not

know

the

angle

of

the first

one

.

In

such

cases

the selection

of

the first

two

ratios is

very

much

arbitrary. A heuristic

recommendation

is

to

use

in

the first

experiment

MI!M2»

I and in the second

MI!Ml«

I.

If

the

gains

are

known

as a result

of

prior

knowledge

,

we

recommend

the following steps.

In

the first experiment use

(4.5)

Then

if

<I>

<

<l>d,

increase M t/M2 by a certain factor

and

if

<I>

>

<l>d

decrease

it

by

the

same

factor.

While

there

is no solid

mathematical

basis

for this selection,

it

yields, in a variety

of

examples

,

two

good

starting

points

for the next step.

The

crucial

part

of

the

algorithm

is the

third

experiment.

We

approximate

the function f in (4.4) by the straight line

(4.6)

From

the

results

of

the first

two

experiments

we

solve for the

constants

bl

and

bl .

Substituting

(4.6)

into

the

desir

ed

75

relation (4.3)

we

get

(4.7)

If

the

approximation

(4.6)

is

perfectly accurate then

(MI!M2h

leads

exactly

to

the desired critical point.

Since

it is not, there

will be

some

error.

We

define

a

tolerance

E

and

stop the

algorithm

if

(4.8)

Otherwise

we

continue

in the

same

fashion as in

experiment

3

where

the best

two

experiments,

i.e. those which are

closer

to

<l>d,

play the role

of

experiments

I and 2 in

equations

(4.6)-

(4.7).

The

algorithm

shows

excellent

convergence

properties

and

in

most

cases

the

number

of

required

experiments

does

not

exceed

four.

This

is

demonstrated

in the

example

in the

next

section.

An

alternative

identification

algorithm

is

presented

in

(Zgorzelski,

1988

and

Zgorzelski

et

aI., 1990).

That

method

uses

only

one

relay

while

the

other

controller

is replaced by a

constant

gain

whose

value

is

updated

based

on

previous

experiments

.

The

steady

state

gains

are

calculated

from

additional

two

step

change

experiments.

In

all the examples that

we

solved,

the

method

suggested

here

converged

to the

desired

critical point faster than the

one

in

(Zgorzelski

et

aI.,

1990). FurthemlOre, there are

cases

where the latter method did

not

converge

at all

or

even led to unstable

systems

during the

process

of

identification.

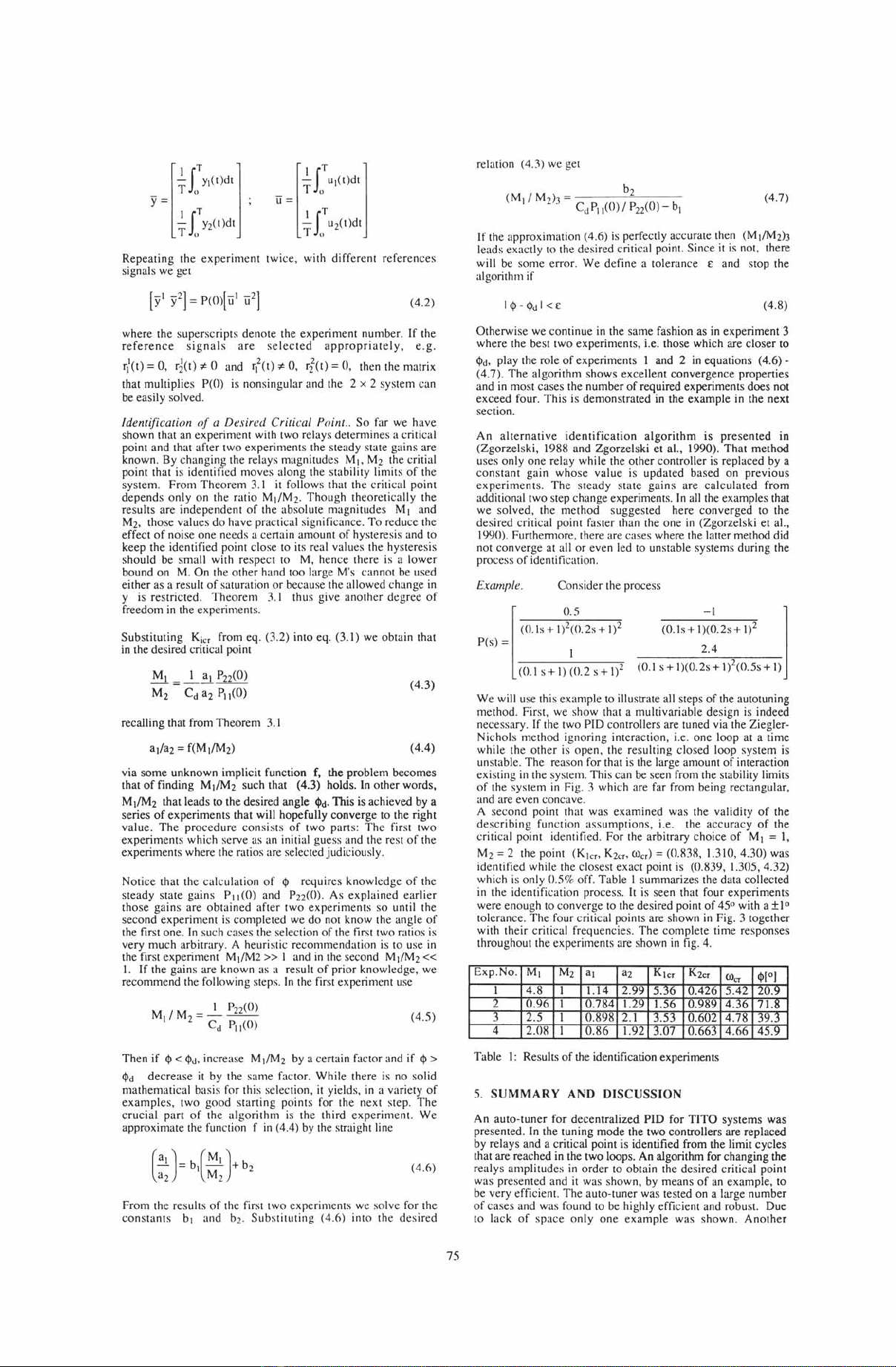

Example.

Consider

the process

-I

1

(O.ls + 1)(0.2s +

1)2

2.4

0.5

pes) =

(0 I

s+

1)(0.2s+

1)2(0.5s+

I)

(0.1

s+

I)

(0.2

s+

1)2

We

will use this

example

to illustrate all steps

of

the autotuning

method

. First, we

show

that a

multivariable

design

is indeed

necessary. If the

two

PID controllers

are

tuned via the Ziegler-

Nichols

method

ignoring

interaction, i.e.

one

loop

at a time

while

the

other

is

open,

the

resulting

closed

loop

system

is

unstable.

The

reason for that is the large

amount

of

interaction

existing in the system.

This

can

be seen from the stability limits

of

the

system

in Fig. 3 which are far from being rectangular,

and are even concave.

A

second

point that

was

examined

was

the validity

of

the

describing

function

assumptions

, i.e. the

accuracy

of

the

critical point identified.

For

the arbitrary

choice

of

MI =

I,

M2 = 2 the point (K lcr,

Kl

cr

, w

cr

) = (0.R38,

1.310,4.30)

was

identified

while

the closest

exact

point is (0.

839

,

1.305,4.32)

which is

only

0.5% off.

Table

I

summarizes

the data collected

in the

identification

process. It is seen that four

experiments

were

enough

to

converge

to the desired point

of

45" with a ±Io

tolerance

.

The

four critical points are shown in Fig. 3

together

with

their

critical

frequencies

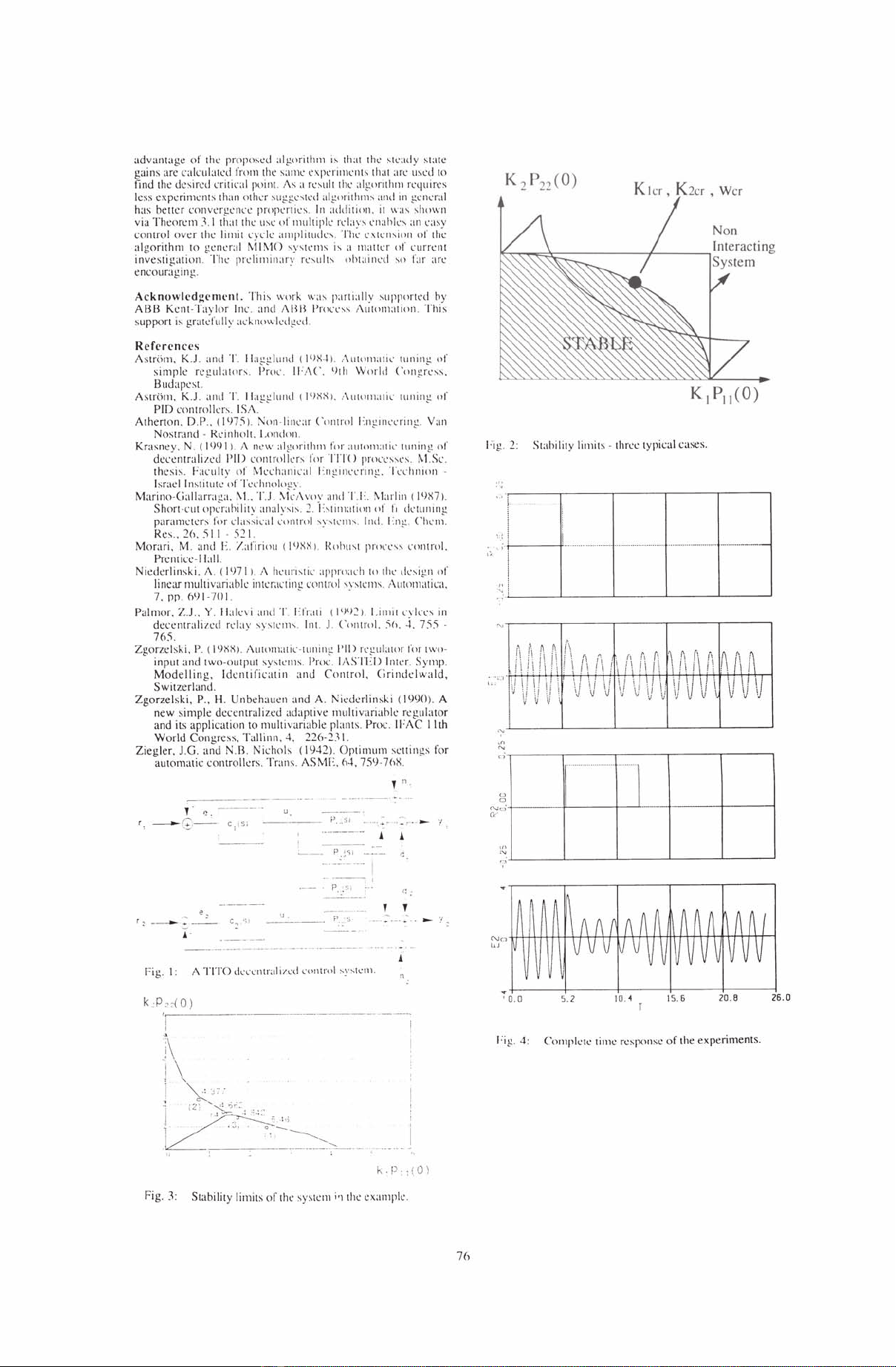

.

The

complete

time

responses

throughout the

experiments

are shown

in

fig. 4.

Exp.No.

MI

M2

al

a2

Klcr

K2cr

wc,.

<1>[0)

I

4.8

I

1.14

2.99

5.

36

0.426

5.42

20.9

2

0.96

I

0.784

1.29

1.56

0.989

4.36

71.8

3

2.5

I 0.R98 2.1

.3

.

53

0.602

4.78

39

.3

4 2.0R I 0.

86

1.92

3.07

0.663

4.66

45.9

Table I : Results

of

the identification experiments

5.

SUMMARY

AND

DISCUSSION

An

auto-tuner

for

decentralized

PlO

for

TITO

systems

was

presented. In the

tuning

mode

the

two

controllers

are

replaced

by relays

and

a critical point is identified from the limit

cycles

that are reached in the

two

loops.

An

algorithm for changing the

realys

amplitudes

in

order

to obtain the desired critical point

was

presented

and

it

was

shown,

by

means

of

an

example,

to

be very efficient.

The

auto-tuner

was tested on a large

number

of

cases

and was found to be highly efficient and robust.

Due

to

lack

of

space

only

one

example

was

shown

.

Another

advantage

or

th

e:

[lro[lme:d ;d

gor

itlull is that t

he

"e;

ld

y

"ate

ga

in

s arc calc

ul

at

ed

fwm

the same

L"

p<:rin1ent

s

th

;

1I

ar

e:

med to

fi

nd

th

e desired

cr

i

ti

c;

d point. As a

r<:>

ult the

al

gorithm requ ires

le

ss

e

xpaim

en

ts

th

an o

th

er suggcsted algllrithms a

nd

in

gcnc

ra

l

has better convergcncc prope

rt

ics. In ;Iddit ion. it

\\,;IS

shllwn

v

ia

Theorcm 3.1

th

;

1I

t

he:

u"

of multiple rL'

Ia

\,s

en;d1ks an casy

control over the lim

it

c)'L'

1c

;Im

plitud e.s. Thc

L'\l

Cn

si

lln

of

th

e

al

gor

ithm to

ge:

ncral M I MO systL

'm

s is ;1 matt

er

Ilf current

investigation. T

hc

prelin

1ina

r

\'

rc

sults o

bt

aincd

\(

'

fa

r a

rc

encourag

in

g.

Ac

knu

wlcdgc nll'lIt. This work

w;"

partially supported hy

ABB

Kcnt-

Ta

vl

or

Inc and AIlIl I'ro

CL'SS

Au

tll

m;

lIi

on. T

hi

s

s

U[lp

o

rt

is grat

:r

u

lly

ack nowledgcd.

Referen

ces

Astr(im. K.J. a

nd

T.

lI

a~~lun

d

(I')

X-l).

,\uto1l1

;lI

ic tunin!.:

of

sim[llc r

q.!

ul

;

lI

or

s.

I

)

~oc

II'AC.

')

Ih World ('Ilngr'css.

Budapes

t.

As

tr

om.

KJ

. and T.

lI

a

~~lun

d

( I

')XX

I.

,\ ul

om

al

iL

'

l

u

ni

n~

of

PID controlle

rs.

I

SA

."

,

Atherton, D.P

..

(1<)

75

).

N

on

-

lin

ear Cllnlrol

Ln

~

in

L

·

erin

~

.

Van

Noslrand -

Rci

nholl. London . "

Krasnev.

N.

( I')l) I

).

A new

a

l

~or

il

h

m

fill'

a

UI,"1

1;

lI

i

L'

tunin

~

of

dcc

~

n

tr

a

li

ze

d

I'ID

co

ntrol

Ins

f

or

TIH)

pro

C·c

ss

L·

S.

r-.(Sl'.

thesi

s.

Facu

lt

\'

of Mcchanical

L

n~inL·L'ri

n

~.

T

L'L

'hnion -

Israc

ll

n

st

ilu

te'

of

T

ec

hn

ol

o

~

\

'

' ,

Marino-

Ciall

a

rr

;lga.

,,

1..

TJ .

\-I

L:

'

'''

o\,

an

d

TY

.

r-.

brl

in (

1')

X7).

Short-C

UI

opc-rahilily analys

is.

2.

Lslim;llillnllf f,

dC

lullin g

[laramcters f

or

classic

'a

l control sys

IL·n1s.

I

nd

. Lng.

('h

em.

Res

..

26.

:;

I I

52

1.

Morari, M. alld E. I .afiriou ( I

')

XX

I.

Rohusl

IlI"ll

eL

'ss clllltml.

Pren

ti

ce-Ila

ll

.

Niederlinsk

i.

A. (I '

)7

I

).

A h

L'u

r

"l

iL' apprll;

IL'i

1 I

II

Ihe

'ks

ig

ll

of

linear multiv

ari

ablc

illlcrac

·

t

i

n ~

contwl

"'ste

ms. Autom

ati

ca,

7.

pp

.

6'J1

-

71l

1 ' -

Palmor.

ZJ

..

Y. I

ble\

'i a

lld

'I' I

fLll

i ( I

'

)l)

~)

.

Limil l'\'

iL'e

s in

decenlralized

re

la

y sy

SlL·nl\

. l

il

t.

J. Cllll lro l. )

1,

. -

i.

75)

-

765.

Zgorzelsk

i.

P. (

Il)

XX).

AU

lomatic-

tu

ni

ng

I' ll)

rL

'gu

la

lllr for two-

input and two-output systcn

1s

.

I'w

c.

lASTED In

te

r.

Symp.

Mode

ll

in

g, I

dcn

ti

fi

cati n

and

Contr

ol, Cirindclwald,

Switzerland.

Zg

orzelski, P

..

H. Unbe hauen and A. Nicderlinski (

1<)<)Il

).

A

new simple decentralized ada[lt

iv

e mu

lt

ivariahlc

re

gu

la

t

or

and i

ts

applicat

io

n to multi variable rlant

s.

PW

l'.

II

''AC I I th

World Cong

re

ss. Ta

ll

in

n. 4, 226-

231

Ziegler, J.G. and

N.

B. Nichols (

19

42).

Ortim

um scttings

fo

r

automatic

co

ntroller

s.

Trans. ASME.

0-1

. 7 5

<)

-7 (

,'1',

.

, . 0

r

~

~:--.

C;

,

Si

e _

(:

~

...

---

r

c...,

,'

;)

u.

P

.,5)

~__

P

,

.

~"il

__

~_

--~.-

--- i

-

---,

p

..

~;i

r"

'

----

--

Fi

g.

I:

A 1'I

TO

dL'

L'c

lllrali

/c

d

L',,,lIJ'll

1 system.

, n

,

n .

Fig. 3: Sta

bi

l

it

y limits of t

he

system ;

'1

th

e examp

le

.

-

.,

76

K

ler,

K2cr ,

Wcr

Non

Fig. 2: Stability limi

ts

- three typical cases.

.'

~--

-,--

---.--

--,---

--.----.

,

;.

1-

--

--1

..

......

.........

......

.....................

..

....

....

.........

.. ..

"

'

L-

______

L-

____

~

__

____

~

______

-L

______

~

!\'\

~~

1\

(, r' \

~\

{\

j\

fd\

/1

; \

rl

!'\

.

1\

il!1

1\

1\

! 1 1\ ! 1

111\

1\

1\

II !\ !

1\

, iJ

I!

U

tI

\

I:

ij

. j

\1

\1

\1

\

\1

V

11

\

le

i

\!

\}

iJ

\i

11

i V i

~

V V V : V "

\;

V J

\i

\1

,n

~

T""-------r

-------,r_------,-------

-r-------,

u

o

~)t

:.

i

>--

--

--

'"

"

-

....

· 1

""

L

______

....L

__

____

....JL.

____

__

..L

______

....L

______

--'

No

-U-I+-I+-I+

++

-I--i

4-4+1-++-t+

I+

ffi-+-I-+l+hl-t++-I

+,H

"j

, 0. 0 5. 2

la

.

~

15. 6 20.8

26

. 0

Fig. 4: Complete time

re

sponse

of

the experiment

s.

![Giáo trình Thực hành Truyền động điện Trường Đại học Bà Rịa - Vũng Tàu [Mới nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2026/20260310/hoaphuong0906/135x160/11121773283865.jpg)

![Giáo trình Thực hành SCADA Trường Đại học Bà Rịa - Vũng Tàu [Mới nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2026/20260310/hoaphuong0906/135x160/94061773283866.jpg)

![Tài liệu học tập La bàn từ [mô tả/định tính]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2026/20260310/hoaphuong0906/135x160/25191773287376.jpg)

![Tài liệu học tập Thiết kế hệ thống nhúng [mới nhất, đầy đủ]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2026/20260305/hoatulip2026/135x160/37051773135929.jpg)

![Giáo trình Điều khiển khí nén thuỷ lực Phần 2: [Mô tả/Chủ đề cụ thể của phần 2]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2026/20260302/camtucau2026/135x160/11911772768225.jpg)

![Giáo trình Điều khiển khí nén thuỷ lực Phần 1: [Mô tả/Định tính thêm nếu cần]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2026/20260302/camtucau2026/135x160/51511772768225.jpg)

![Giáo trình Điều khiển số Phần 2: [Thêm từ khóa mô tả nội dung chương trình]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2026/20260302/camtucau2026/135x160/37201772766913.jpg)