DALAT UNIVERSITY

FACULTY OF FOREIGN LANGUAGES

LINGUISTICS 2

Áp dụng cho sinh viên từ K45

Selected and compiled by Hồ Thị Giáng Châu

FOR DLU STUDENTS ONLY, NOT FOR SALE

Lam Dong - 2023

P

PA

AR

RT

T

O

ON

NE

E:

:

M

MO

OR

RP

PH

HO

OL

LO

OG

GY

Y

–

–

T

TH

HE

E

A

AN

NA

AL

LY

YS

SI

IS

S

O

OF

F

W

WO

OR

RD

D

S

ST

TR

RU

UC

CT

TU

UR

RE

E

I. WORDS AND THEIR PARTS

For most people, the most basic and most tangible elements of a language are certainly its

words. “There’s no such word”, you’ve heard people say. Or, “What does the word futharc

mean?” Or, from someone doing a crossword puzzle, “What’s a three-letter word for

excessively?” We say that one person always uses “two-bit” words, while someone else exhibits a

preference for “four-letter” words. Intuitively, people seem to have clear notions of what a word

is.

When it comes to identifying meaningful units smaller than a word, our intuitions are not

so clear. Though we readily intuit that car, walk, sing, and tall have a single meaningful element

each and that bookstore, sunrise, and sidestep have two each, our intuitions are less certain about

the number of meaningful elements in words such as bookkeeper, sneakers, women’s,

impracticality, fenced, resumed, and presumption. This part of the book examines the

segmentation of words into their meaningful elements, the principles that govern the composition

of words from meaningful elements, and the functions of words and word parts in sentences. We

describe what it means to know a word and the ways in which a language can expand its stock of

words.

What it means to know a word

Consider what a child must know when it knows a word in its language. A child able to

utter a sentence like My new doll can cry knows much more about the word doll than the kind of

toy it refers to. The child knows what sounds make up doll and in what sequence they occur, as

well as how to use doll in a sentence. The child also knows that doll is a common noun (and hence

can be preceded by the possessive pronoun my, as here, or by an article like a plus an adjective);

that doll is a count noun (that is, it can be followed by a plural marker -s, in contrast to mass

nouns like milk and sugar, which do not take -s); and that the plural of doll is formed regularly

and is not an irregular like teeth or deer.

2

Thus, knowing a word requires having at least four kinds of information:

1. Phonological: what sounds the word contains and their sequencing (we discussed this in

the previous course)

2. Semantic: the meanings of the word (to be discussed in part 2 of the book)

3. Syntactic: what category (noun, verb, etc.) the word belongs to and how to use it in a

sentence

4. Morphological: how related words, including plurals (for nouns) and past tenses (for

verbs), are formed (a topic of this course)

Knowing even the simplest word requires that phonological, morphological, syntactic, and

semantic information be stored in the mind’s dictionary (the lexicon) as part of that word’s mental

representation.

There are certain parallels between the kinds of information stored in the lexicon and the

information that can be found in an ordinary desk dictionary. In a desk dictionary, basic

phonological, semantic, morphological, and syntactic information is found along with information

that neither children nor adult speakers need to possess in order to speak a language –

information, for example, about a word’s orthographic representation or about its etymology (the

history of its phonological development and of the semantic path it followed in getting to its

current meaning). In addition, dictionaries sometimes provide illustrative sentences for words or

actual citations from well-known sources. Obviously, children will not normally have any

orthographic, etymological, or illustrative information in their lexicon.

II. MORPHEMES: THE MEANING –BEARING CONSTITUENTS OF WORDS

We now turn to the smallest units of language that can be associated with meaning or

grammatical categories. As it happens, those units need not be words.

3

English speakers are aware that words like girl, ask, tall, father, uncle, and orange cannot

be divided into smaller meaningful units. Orange, for example, is not made up of o + range or or

+ ange or ora + nge. Nor is father made up of, say, fath and er. Such words are said to be simple

words. But many words (which are called complex words) do have more than one meaningful

part. Oranges, fathers, grandmother, asks, asked, asking, homemade, taller, and tallest have two

elements each. Other words having more than one element that contributes to their overall

meaning include beautiful, churches, supermarkets, bookshelves, and television. A set of words

can be built up by adding certain elements to a core element. For example, built up around the

core element true is the following set of words:

truer untrue truthfully

truest truth untruthfully

truly truthful untruthfulness

Speakers of English recognize that these words share a stem whose meaning or lexical

category has been modified or changed by the addition of other elements.

The meaningful elements of a word are called morphemes. In other words, a morpheme

is the smallest unit of language that carries information about meaning or function. Thus, true is a

single morpheme; untrue and truly contain two morphemes each; and untruthfulness contains five

(UN + TRUE + TH + FUL + NESS). Truer, with the two elements TRUE and –ER (“more”),

means “more true”. The morphemes in truest are TRUE and –EST (“most”); in truly, TRUE and –

LY; in untrue, TRUE and UN-; in truthful, TRUE + - TH + -FUL.

We have been using the word “meaningful” somewhat loosely, for it is only by stretching

the use of that word a bit that we can call –er in truer and –ed in looked meaningful elements.

Morphemes can indeed have meaning, as with true and look, but they can also represent a

grammatical category, such as comparative degree or past tense.

Morphemes cannot be equated with syllables. On the one hand, a single morpheme can

have two or more syllables, as in harvest, grammar, river, gorilla, hippopotamus, and

Connecticut. On the other hand, there are sometimes two or more morphemes in a single syllable,

4

as in judged (JUDGE + ‘PAST TENSE’), dogs (DOG + ‘PLURAL’), and men (MAN +

‘PLURAL’), with two morphemes each, and men’s with three morphemes (MAN + ‘PLURAL’ +

‘POSSESSIVE’).

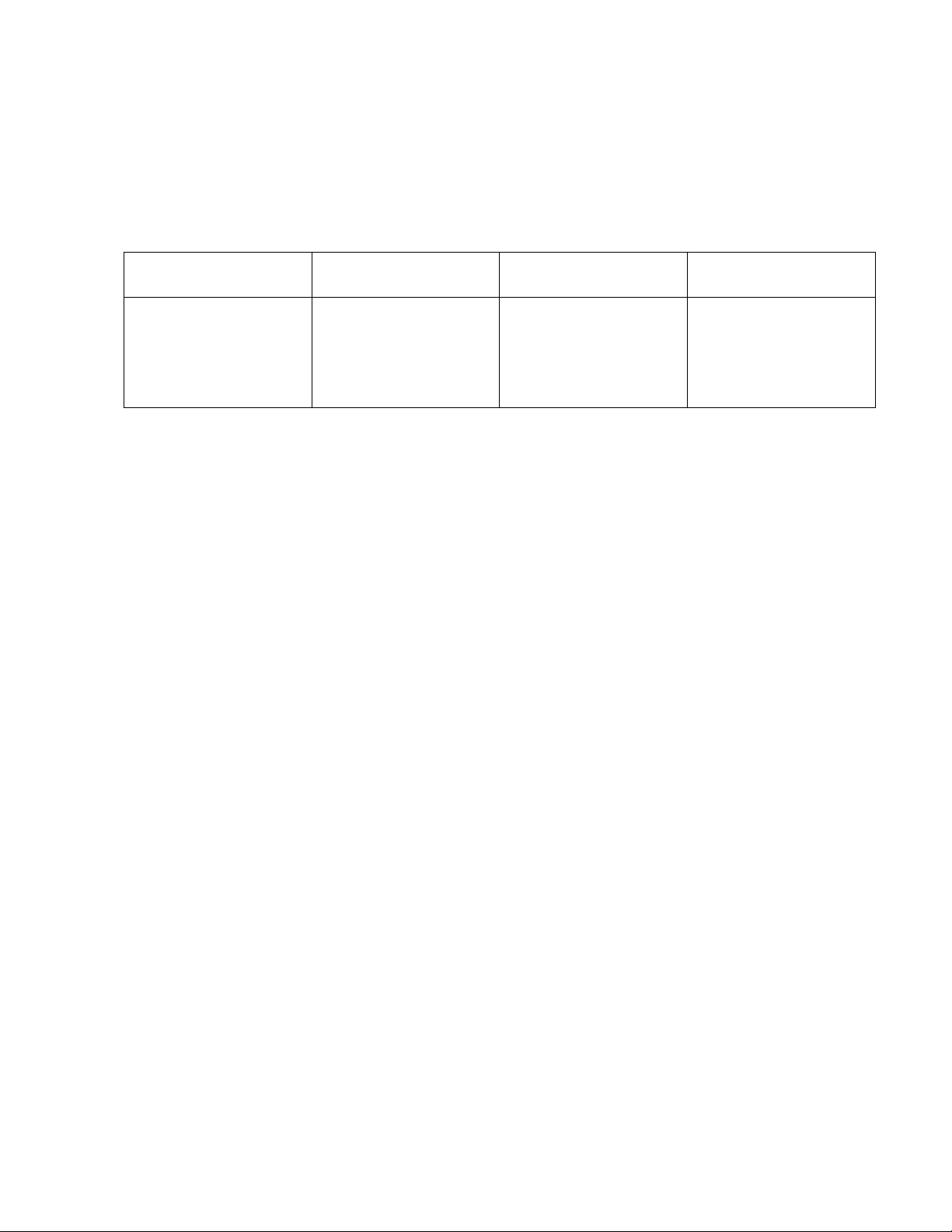

Table 1 Words consisting of one or more morphemes

One Two Three More than three

and

boy

hunt

act

boys

hunter

active

hunters

act-iv-ate

re-act-iv-ate

Summary

Morphemes are the building blocks of words. A word may contain only one morpheme,

making it a simple word, or a word may contain more than one morpheme, making it a complex

word. Below are some hints for determining the number of morphemes that a word contains.

A morpheme can carry information about meaning or function. For example, the word

haunt cannot be divided into the morphemes h and aunt, since only aunt has meaning.

However, the word bats has two morphemes, since both bat and –s have meaning. The –s,

of course, means that there is more than one.

The meanings of individual morphemes should contribute to the overall meaning of the

word. For example, pumpkin cannot be divided into pump and kin, since the meaning of

pumpkin has nothing to do with the meaning of either pump or kin.

A morpheme is not the same as a syllable. Morphemes do not have to be a syllable, or

morphemes can consist of one or more syllables. For example, the morpheme treat has

one syllable, the morpheme dracula has three syllables, but the morpheme –s (meaning

‘plural’) is not a syllable.

Often during word formation, changes in pronunciation and/or spelling occur. These do

not affect a morpheme’s status as a morpheme. For example, when –y is attached to a the

![Bài giảng Văn học phương Tây và Mỹ Latinh [Tập hợp]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20251003/kimphuong1001/135x160/31341759476045.jpg)