Quality zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of

Service (QOS) and

Network Performance (NP) zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

The maintenance of good quality for any product or service (i.e. its ‘fitness for purpose’ and its

price) is of supreme importance to the consumer and therefore requires utmost management

attention. However, although it is easy enough to test a tangible product to destruction, measure-

ment of the quality of a service is more difficult. In telecommunication the customer is left with

nothing more tangible than his or her own perception of how well the communication went. On a

datalink the errors that have had to be corrected automatically are barely appreciated, while in

conversation unobtrusive bursts of line noise may go unnoticed. This is not to say that loss of

data throughput on a datalink caused by continual error correction is of no concern to the

customer, nor does it mean that noises which disturb conversation are acceptable. What we really

mean is that in measuring service quality, due regard must be paid to anything of importance that

the customer perceives and remembers. Concentration on setting and meeting quality targets

should be paramount in planning and administration. Insufficient attention to them is the road to

customer dissatisfaction and loss of business. This chapter reviews some aspects of communica-

tions quality and the practices of management, with examples of the commoner quality

parameters and control measures used by the world’s major operators. zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

34.1

FRAMEWORK FOR PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT

Good management of whatever industry demands the use

of

simple, structured and

effective monitoring tools and control procedures

to

maintain the efficiency of the

internal business processes and the quality of the output. When all is running smoothly

a

minimum of effect should be required. However, to be able quickly to correct defects

or

cope

with abnormal circumstances, measurable means

of

reporting zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

faults

or

excep-

tions

and rapid procedures for identifying actionable tasks are required. The framework

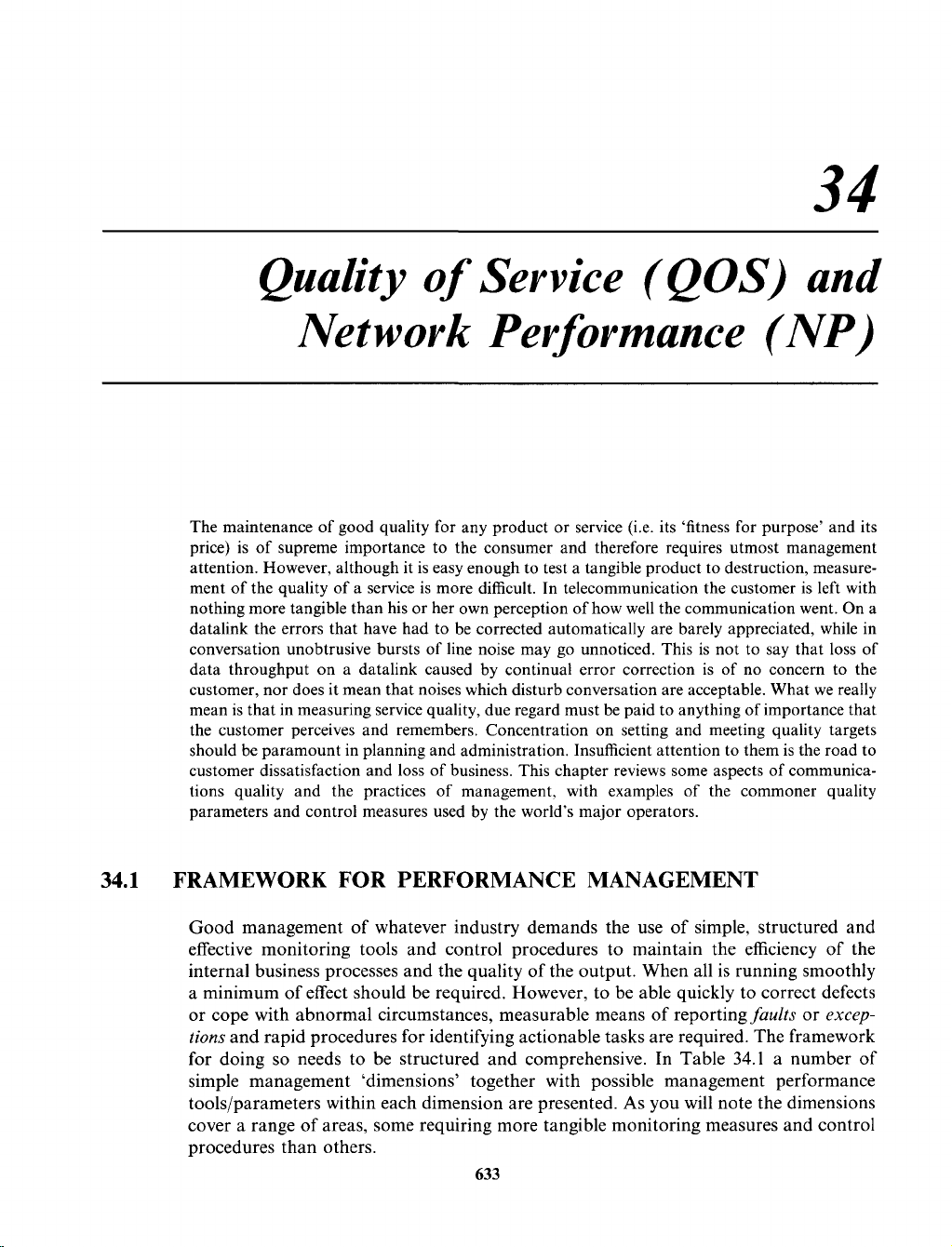

for doing so needs to be structured and comprehensive. In Table 34.1

a

number of

simple management ‘dimensions’ together with possible management performance

tools/parameters within each dimension are presented.

As

you will note the dimensions

cover

a

range

of

areas, some requiring more tangible monitoring measures and control

procedures than others.

633

Networks and Telecommunications: Design and Operation, Second Edition.

Martin P. Clark

Copyright © 1991, 1997 John Wiley & Sons Ltd

ISBNs: 0-471-97346-7 (Hardback); 0-470-84158-3 (Electronic)

634

QUALITY zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

OF

SERVICE

(QOS)

AND NETWORK PERFORMANCE (NP)

Table

34.1

Framework for performance management

Dimension Measures/controls

Formal plan and delivery cycle Formal zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

presentation

and

agreement

of company strategy,

(organizational framework) policy, guidance and plans.

Regular review.

Framework for business ‘value’ assessment and assurance.

User support

(fit for purpose)

Supplier performance

(quality of supply)

Quality performance

(effectiveness)

Financial performance

(efficiency)

Technical performance

(efficiency)

Resource management

(efficiency)

Evolution of networks

(responsiveness)

User comprehension of services (by questionnaire).

Swift elimination of problems (full complaint log).

Maintaining professional attitude with suppliers.

Monitoring and demanding swift lead times.

Meeting targets for repair performance.

Meeting user needs (number of complaints).

Number of lost messages (e.g. percentage

of

data lost)

Percentage of ‘down-time’ during normal business hours.

Measure of delay (e.g. propagation delay, or backlog of

orders/messages).

Measure of congestion (e.g. percentage calls lost zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

-

callers

frustrated).

Repair performance (e.g. percentage not repaired in

target time).

Connection quality (e.g. percentage customers satisfied).

‘Cost of poor quality’ (i.e. that correcting avoidable

faults).

Return on capital investment.

Shareholders financial return.

Cost actually spent can be compared with competitors or

alternative suppliers.

Internal chargeout rate for telecom services (e.g. ‘pounds

per bit-mile’).

Compatibility of networks can be adjudged by measuring

the money spent

on

interworking or upgrading and

comparing it with total system value.

Asset inventory and management (needs to be accurate

and up to date).

Cost per task.

Adequate resourcing to meet target service lead times.

Head count and man-hours should be maintained on

target.

Network upgrades should be properly planned and meet

their budget.

There should be steps to give ‘benefits’ assurance.

The response time of new software and computer

networks should be according to plan.

The networks should be adaptable.

QUALITY:

A

MAREKTING

VIEW zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

635

34.2

QUALITY: A MARKETING VIEW zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

To

look at a network from the customer’s viewpoint we need to understand his reasons

for using telecommunications services. It is a mistake to generalize about all customers

as ‘wanting to convey information over long distances’, as that takes no account of the

service in use, or of each customer’s individual purpose or zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

application.

It is, after all, a

Figure

34.1

A

customer’s perception

of

quality. Get the basics right before worrying with the

frills. Drawing by Patrick Wright. zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(Courtesy

of

M.

P.

Clurk)

636 zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

QUALITY

OF

SERVICE

(QOS)

AND NETWORK PERFORMANCE (NP)

fundamental of marketing that products should be attuned to the markets and

customers they are intended to serve. Thus the motivations and interests of someone

who is out for the evening in calling home from a payphone, are quite different from the

needs of a large multi-national company wishing to convey vast volumes of computer

data around the world on sophisticated and dedicated networks at any hour of the day

or night.

It may be that the same network infrastructure can accommodate the service needs of

a number of different markets or customer ‘clubs’ but it must do

so

without compromise.

One example of a network capable of supporting a number of services

is

the public

telephone network, and it must run at optimum quality not only for human conver-

sation, but also for facsimile machine interconnection. A more advanced example of

integrated services networks is the zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

integrated services digital network zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(ZSDN)

discussed

in Chapter 10 and the

B-ZSDN

of Chapter

25.

Customers’ communication needs can often be met in a number of alternative fashions,

ranging from travelling in person, using the postal service, the telephone, telex, packet

switching, and high speed data telecommunications services. Pitching a given service to

meet a given need is the job of telecommunications marketing specialists who determine

its relevant qualities, expressed as a number of measurable parameters. An example of

such a ‘quality parameter’, used commonly by telephone network operators is the

percentage of calls completed.

Not only is this a fair measure of network congestion, it is

also a good predictor

of

the level of customer frustration.

34.3

QUALITY

OF

SERVICE (QOS) AND

NETWORK PERFORMANCE (NP)

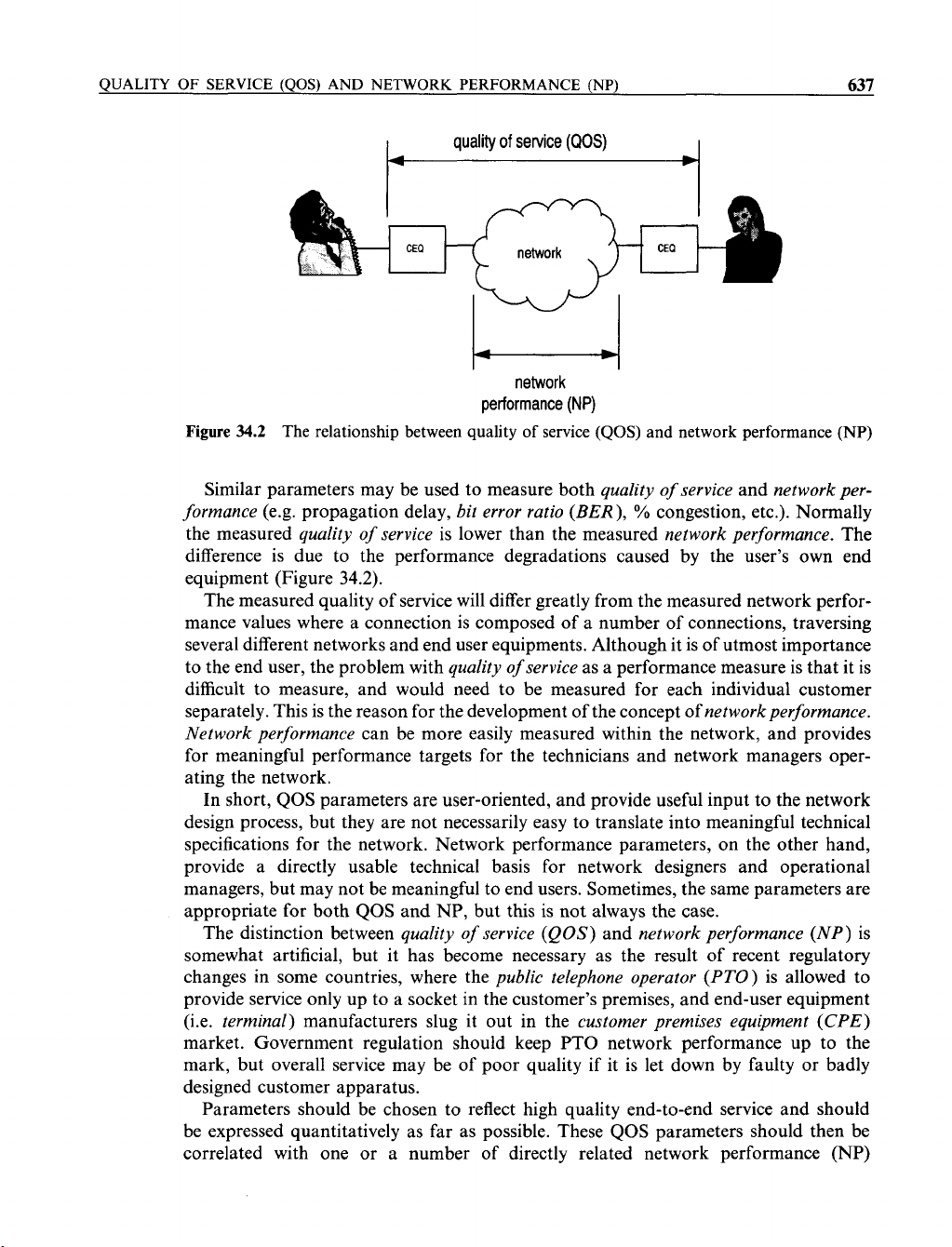

You may have realized in our example above that the percentage of answered calls is

dependent not only on network congestion, but also on the availability of somebody at

the destination end to answer the telephone. Thus the

quality of service

enjoyed by the

customer depends on a number of factors in addition to the performance of the net-

work. ITU-T has also drawn this distinction, and its general recommendations on the

quality of telecommunications services recognize two separate categories of perfor-

mance measurement zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

0

quality of service

(QOS)

0

network performance

(NP)

Quality of service

measurements help a telecommunications service or network pro-

vider to gauge customers’ perceptions of the service.

Network performance

parameters,

on the other hand, are direct measurements of the performance of the network, in

isolation from customer and terminating equipment effects. Thus

quality of service

encompasses a wider domain than

network performance,

so

that it is possible to have a

case of poor overall

quality of service

even though the

network performance

may be

excellent. The relationship of

quality of service

to

network performance

is shown in

Figure

34.2.

QUALITY OF SERVICE (QOS) AND NETWORK PERFORMANCE (NP)

637 zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

quality zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of

service zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(QOS) zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

W

network

performance

(NP)

Figure

34.2 The relationship between quality of service zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(QOS)

and network performance (NP)

Similar parameters may be used to measure both

quality zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of

service

and

network per-

formance

(e.g. propagation delay,

bit error ratio

(BER),

%

congestion, etc.). Normally

the measured

quality

of

service

is lower than the measured

network performance.

The

difference is due to the performance degradations caused by the user’s own end

equipment (Figure

34.2).

The measured quality of service will differ greatly from the measured network perfor-

mance values where a connection is composed of a number of connections, traversing

several different networks and end user equipments. Although it is of utmost importance

to the end user, the problem with

quality

of

service

as a performance measure is that it is

difficult to measure, and would need to be measured for each individual customer

separately. This is the reason for the development of the concept of

networkperformance.

Network performance

can be more easily measured within the network, and provides

for meaningful performance targets for the technicians and network managers oper-

ating the network.

In short,

QOS

parameters are user-oriented, and provide useful input to the network

design process, but they are not necessarily easy to translate into meaningful technical

specifications for the network. Network performance parameters, on the other hand,

provide a directly usable technical basis for network designers and operational

managers, but may not be meaningful to end users. Sometimes, the same parameters are

appropriate for both

QOS

and NP, but this

is

not always the case.

The distinction between

quality

of

service

(QOS)

and

network performance

(NP)

is

somewhat artificial, but it has become necessary as the result of recent regulatory

changes in some countries, where the

public telephone operator

(PTO)

is allowed to

provide service only up to a socket in the customer’s premises, and end-user equipment

(i.e.

terminal)

manufacturers slug it out in the

customer premises equipment

(CPE)

market. Government regulation should keep PTO network performance up to the

mark, but overall service may be of poor quality if it is let down by faulty or badly

designed customer apparatus.

Parameters should be chosen to reflect high quality end-to-end service and should

be expressed quantitatively as far as possible. These

QOS

parameters should then be

correlated with one or a number of directly related network performance

(NP)

![Biến Tần FR-A700: Sổ Tay Hướng Dẫn Cơ Bản [Chi Tiết]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2019/20191130/cac1994/135x160/1741575103503.jpg)

![Xử lý số tín hiệu: Tài liệu thí nghiệm [Chuẩn SEO]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2018/20180821/danhvi27/135x160/7141534836177.jpg)

![Ngân hàng câu hỏi ôn tập Anten và truyền sóng [Năm]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20250115/sanhobien01/135x160/18471768473368.jpg)