C-Terminal extension of a plant cysteine protease

modulates proteolytic activity through a partial inhibitory

mechanism

Sruti Dutta, Debi Choudhury, Jiban K. Dattagupta and Sampa Biswas

Crystallography and Molecular Biology Division, Saha Institute of Nuclear Physics, Kolkata, India

Keywords

C-terminal extension; cysteine proteases;

modulation of proteolytic activity;

papain-like; thermostable

Correspondence

S. Biswas, Crystallography and Molecular

Biology Division, Saha Institute of Nuclear

Physics, 1 ⁄AF Bidhannagar, Kolkata

700 064, India

Fax: +91 332 337 4637

Tel: +91 332 337 5345

E-mail: sampa.biswas@saha.ac.in

(Received 14 March 2011, revised 16 May

2011, accepted 22 June 2011)

doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2011.08221.x

The amino acid sequence of ervatamin-C, a thermostable cysteine protease

from a tropical plant, revealed an additional 24-amino-acid extension at its

C-terminus (CT). The role of this extension peptide in zymogen activation,

catalytic activity, folding and stability of the protease is reported. For this

study, we expressed two recombinant forms of the protease in Escherichia

coli, one retaining the CT-extension and the other with it truncated. The

enzyme with the extension shows autocatalytic zymogen activation at a

higher pH of 8.0, whereas deletion of the extension results in a more active

form of the enzyme. This CT-extension was not found to be cleaved during

autocatalysis or by limited proteolysis by different external proteases.

Molecular modeling and simulation studies revealed that the CT-extension

blocks some of the substrate-binding unprimed subsites including the speci-

ficity-determining subsite (S2) of the enzyme and thereby partially occludes

accessibility of the substrates to the active site, which also corroborates the

experimental observations. The CT-extension in the model structure shows

tight packing with the catalytic domain of the enzyme, mediated by strong

hydrophobic and H-bond interactions, thus restricting accessibility of its

cleavage sites to the protease itself or to the external proteases. Kinetic

stability analyses (T

50

and t

1⁄2

) and refolding experiments show similar

thermal stability and refolding efficiency for both forms. These data suggest

that the CT-extension has an inhibitory role in the proteolytic activity of

ervatamin-C but does not have a major role either in stabilizing the enzyme

or in its folding mechanism.

Structured digital abstract

lErvC cleaves ErvC by protease assay (View interaction)

ltrypsin cleaves ErvC by protease assay (View interaction)

Introduction

Papain-like cysteine proteases (EC 3.4.22) from plant

sources are of industrial and biotechnological impor-

tance because these enzymes are better suited to various

industrial processes [1]. A cysteine protease is expressed

as an inactive precursor in a pre-proenzyme form

which contains a signal peptide (pre-), an inhibitory

Abbreviations

CT, C-terminal; E-64, 1-[L-N-(trans-epoxysuccinyl)leucyl]amino-4-guanidinobutane; Erv-C, ervatamin-C; pNA, p-nitroanilide; rmErv-C

+CT

,

recombinant mature ervatamin-C with C-terminal extension; rmErv-C

DCT

, recombinant mature ervatamin-C without C-terminal extension;

rproErv-C

+CT

, recombinant proervatamin-C with C-terminal extension; rproErv-C

DCT

, recombinant proervatamin-C without C-terminal

extension.

3012 FEBS Journal 278 (2011) 3012–3024 ª2011 The Authors Journal compilation ª2011 FEBS

pro-region and a mature catalytic domain [2–4]. Fol-

lowing synthesis, the pre-peptide is removed during

passage to the lumen of the endoplasmic reticulum [2].

The inactive proenzyme subsequently undergoes prote-

olytic processing to produce an active mature enzyme

by autocatalytic cleavage of the propeptide part at the

N-terminus [2]. It is known that the propeptide at the

N-terminus of the protease acts as an intramolecular

chaperone to mediate correct folding of the protease

[2]. The mature catalytic domain of the enzyme of this

family has a molecular mass of 21–30 kDa and

shares a common fold with papain, the archetype

enzyme of the family. These proteases are folded into

two compact interacting domains of comparable size,

delimiting a cleft which contains the active site residues

cysteine and histidine, forming a zwitterionic catalytic

dyad (Cys

)

...His

+

) [5].

Sometimes a larger precursor is also synthesized

which contains a C-terminal (CT) extension ⁄propep-

tide in addition to the abovementioned N-terminal

propeptide flanking the mature protease domain [6,7].

Unlike N-terminal propeptides, the role of CT-exten-

sions (or propeptides) is not yet well established.

Sometimes an endoplasmic reticulum retention signal

Lys-Asp-Glu-Leu (KDEL) is found in the CT-propep-

tide which regulates the delivery of protease precursor

to other cellular compartments [8]. Some other mem-

bers of the papain family from plant sources also con-

tain a larger CT-propeptide domain which shares a

similarity with animal epithelin ⁄granulin and the func-

tion of this domain is reported to be involved in leaf

senescence [6]. In addition, a CT-propeptide without

any specific domain or motif is observed in some

papain-like cysteine proteases from plants like Nicoti-

ana tabacam (Q84YH7), Actinidia chinensis (P00785)

and Vicia sativa (Q41696). In most of the cases, such a

CT-extension contains the vacuolar sorting signal and

is cleaved inter- or intramolecularly after sorting [9].

No conserved sequence motif has been found in the

vacuolar sorting signal at CT-propeptide, rather an

amphipathic-like (hydrophobic and acidic) motif is

generally observed [9,10] at the core of such peptides.

Other than plant systems, a CT-extension found in

a lysosomal cysteine protease (Lpcys2) of Leish-

mania pifanoi, plays a role in the regulation of enzyme

activity [11]. CT-extension in mammalian and yeast

bleomycin hydrolase [12,13] is a key factor which regu-

lates their endo-peptidase or exo-aminopepetidase

activity by blocking the unprimed subsites in the

enzymes.

Ervatamin-C (Erv-C) is a papain-like cysteine prote-

ase (EC 3.4.22) with high stability purified from the

latex of a tropical plant Ervatamia coronaria [14]. The

3D structure of Erv-C reveals an extra disulfide bond,

shorter loop regions and additional electrostatic inter-

actions in the interdomain space, which are thought to

be responsible for its high stability [15]. Sequencing

of the cDNA (from mRNA) of Erv-C from the leaf

of the plant in our laboratory [16], and comparison of

the cDNA-derived amino acid sequence with other

members of the family reveal that Erv-C is synthesized

as a precursor protein and in addition to the pre- (19

amino acids), pro- (114 amino acids) and mature (208

amino acids) parts, it contains an extension of 24

amino acids at the CT of the mature enzyme [16]

(Fig. 1A). This CT-extension was not observed, how-

ever, when the mature Erv-C was purified directly

from the latex of the plant [15].

In this article, we attempt to understand the role of

this CT-extension in zymogen activation, enzyme activ-

ity, folding and stability in vitro at the molecular level

from structural and functional points of view.

Results

Cloning, expression, purification and refolding of

rproErv-C

DCT

and rproErv-C

+CT

Both the proteins, recombinant proervatamin-C with-

out the CT-extension (rproErv-C

DCT

) and recombinant

proervatamin-C with the CT-extension (rproErv-

C

+CT

), were expressed in E. coli as inclusion bodies

with an apparent molecular mass of 41 and

43 kDa (Fig. 1B), respectively, which is consistent

with the estimated molecular masses of their deduced

amino acid sequences. Correct refolding was checked

by gelatin gel assay. The condition and efficiency of

refolding were almost similar for both forms with

> 90% recovery of the folded form from Ni-NTA

purified protein for each (Table S1).

Activation to mature protease

The purified refolded rproErv-C

+CT

could be con-

verted into its mature active form (rmErv-C

+CT

)by

using cysteine (20 mM) as the activator in 50 mMTris

buffer, pH 8.00, at 60 C for 25–30 min, whereas the

purified refolded rproErv-C

DCT

could be converted

into its mature form (rmErv-C

DCT

) by the same activa-

tor in 50 mMNa-acetate buffer, pH 4.5, at 60 C for

45 min (Fig. 2A). Thus the zymogen activation process

occurs at different pH and time of maturation for the

two enzymes. The molecular mass of the mature

enzyme rmErv-C

+CT

is higher (27 kDa) than that

of rmErv-C

DCT

(25 kDa) as observed in the

SDS ⁄PAGE analyses (Fig. 2A). This difference in

S. Dutta et al. Role of C-terminal extension in a cysteine protease

FEBS Journal 278 (2011) 3012–3024 ª2011 The Authors Journal compilation ª2011 FEBS 3013

molecular mass almost fits the theoretically calculated

value for the 24-amino-acid CT-extension. We

expected, therefore, that the CT-extension continued to

remain attached with the mature enzyme even after

autocatalytic processing of rproErv-C

+CT

. Gelatin gel

assay (Fig. 2B) and western blot analyses (Fig. 2C)

also confirmed the retention of the CT-extension in the

mature rmErv-C

+CT

.

Because Erv-C isolated from the latex of the same

plant does not show the CT-extension, the possibility

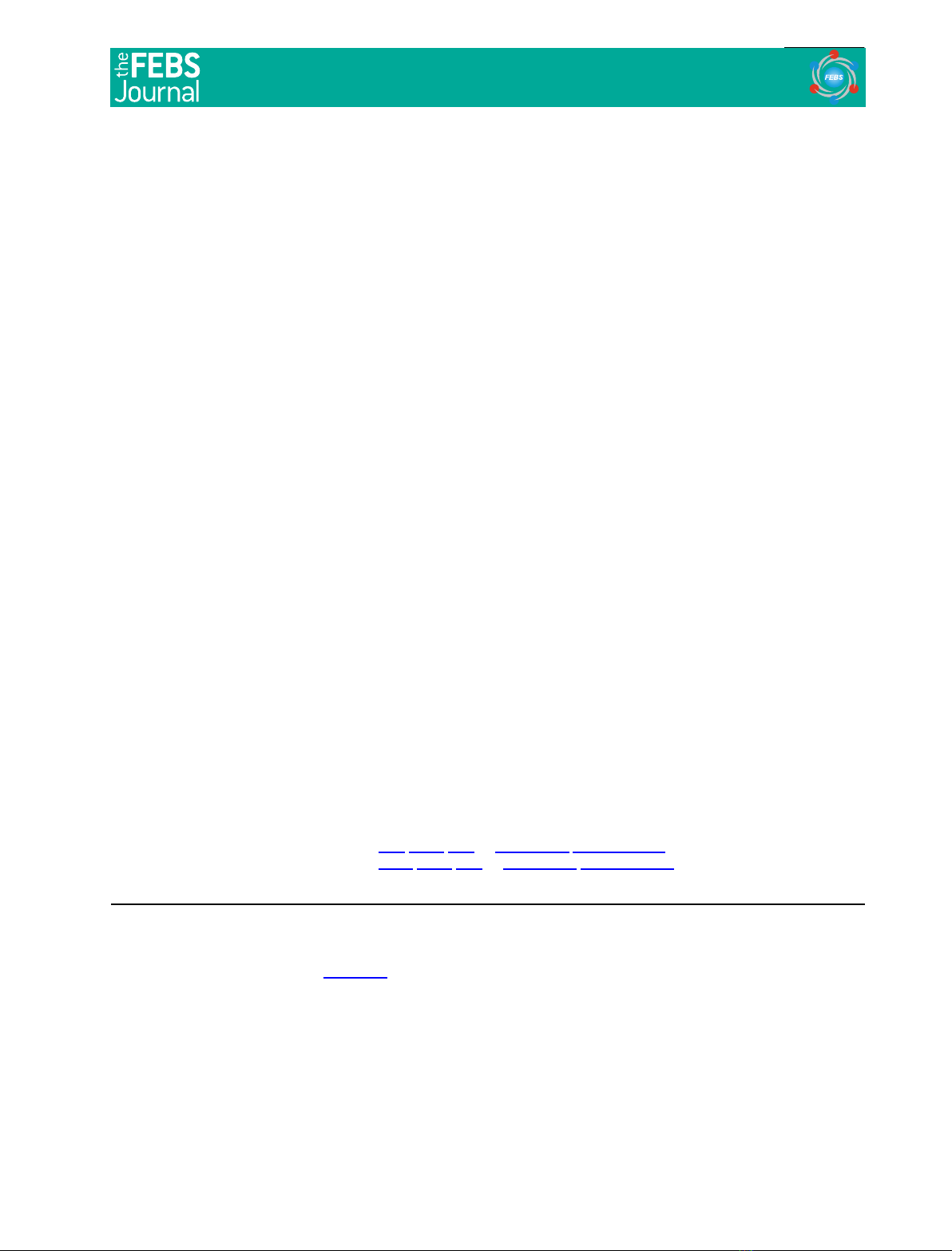

19 aa 114 aa 208 aa 24 aa

Pre N-Pro Protease domain CT - ex

365 aa

H1

I

NPro CT ex

114 aa 208 aa 24 aa

BamH

34 aa

Start

Stop

Xho1

N-Pro Protease domain

Protease domain

CT - ex

380 aa

1

II

NP

114 aa 208 aa

BamH1

34 aa

Start

Stop

Xho1

SS SS G

SSS

S

N-Pro

356 aa

III

MSTLFIISILLFLASFSYAMDISTIEYKYDKSSAWRTDEEVKEIYELWLAKHDKVYSGLVEYEKRFEIFKDNLKFIDEH

NSENHTYKMGLTPYTDLTNEEFQAIYLGTRSDTIHRLKRTINISERYAYEAGDNLPEQIDWRKKGAVTPVKNQGKCG

SCWAFSTVSTVESINQIRTGNLISLSEQQLVDCNKKNHGCKGGAFVYAYQYIIDNGGIDTEANYPYKAVQGPCRAAK

KVVRIDGYKGVPHCNENALKKAVASQPSVVAIDASSKQFQHYKSGIFSGPCGTKLNHGVVIVGYWKDYWIVRNSW

GRYWGEQGYIRMKRVGGCGLCGIARLPYYPTKAAGDENSKLETPELLQWSEEAFPLA

IV

A

B

66 kDa

45 kDa

36 kDa

29 kDa

24 kDa

20 kDa

321

Fig. 1. (A) (I) Open reading frame of Erv-C precursor, pre-pro-ErvC. (II) Recombinant ervatamin-C with C-terminal extension, rproErv-C

+CT

.

(III) rproErv-C

DCT

, recombinant ervatamin-C without C-terminal extension. Red indicates vector portion and ‘aa’ stands for amino acids. (IV)

The amino acid sequence of the open reading frame. The sequence of CT-extension is in red. (B) Lanes 1 and 2, Purified proteins rproErv-

C

+CT

and rproErv-C

DCT

, respectively; lane 3, Molecular mass markers.

Role of C-terminal extension in a cysteine protease S. Dutta et al.

3014 FEBS Journal 278 (2011) 3012–3024 ª2011 The Authors Journal compilation ª2011 FEBS

of removal of the CT-extension by other plant prote-

ases in vivo could not be ruled out. To explore this

possibility, we performed a trans mode activation of

rproErv-C

+CT

in vitro using seven different proteases

(four cysteine proteases Erv-A, -B, -C and papain from

the plant latex; two serine proteases trypsin and chy-

motrypsin from bovine pancreas; one aspartic protease

pepsin from porcine stomach mucosa), each having

sequences specific for their cleavage in the amino acid

sequence of the CT-extension. The activated mature

protein thus generated in each case shows a band at

the same position (27 kDa) like that in the autoacti-

vated enzyme, as observed in SDS ⁄PAGE analyses

(Fig. S1), indicating that these external enzymes can

not cleave the CT-extension. Even with a prolonged

digestion time (24 h), the same result was obtained for

all proteases except trypsin (Fig. S1). Trypsin digestion

for 24 h resulted in a truncated protein at 26 kDa,

slightly above the activated mature rmErv-C

DCT

(25 kDa). This result probably indicates that trypsin

has some accessibility to its sites of specificity (Lys,

which is in position 7 of the CT-extension) (Fig. S2)

and only after a prolonged incubation time can it

result in a band at a slightly lower molecular mass

position, as observed in the SDS ⁄PAGE analysis

(Fig. S1).

Specific activity and optimum temperature of

activity

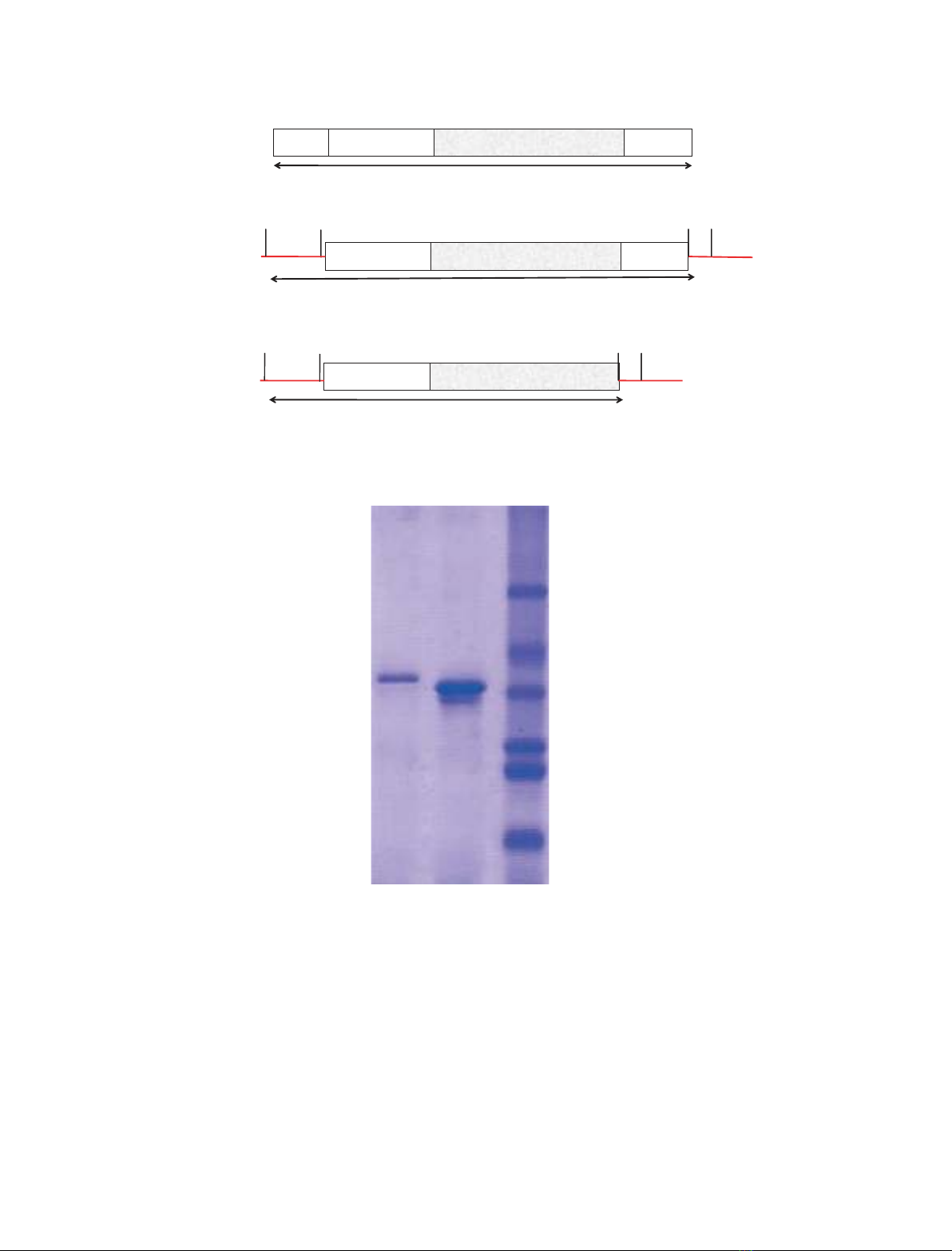

The optimum temperature of activity, T

opt

(Fig. 3), for

both forms is 65 C. Interestingly, it was observed that

rproErv-C

+CT

shows no activity below 45 C and then

activity rises sharply from 60 C onwards, reaching a

maximum at 65 C. In the case of rproErv-C

DCT

,a

gradual increase in activity with temperature was

observed until it reached its maximum at 65 C.

At T

opt

(65 C), the specific activity of rmErv-C

DCT

was found to be almost double that of rmErv-C

+CT

(Table 1). At 37 C, however, rproErv-C

DCT

shows

measurable proteolytic activity, whereas no activity

was seen for rmErv-C

+CT

.

Kinetic measurements of the recombinant

proteins

Kinetic constants of rproErv-C

+CT

and rproErv-C

DCT

were measured at room temperature against N-ben-

zoyl-Phe-Val-Arg-p-nitroanilide (pNA), a tripeptide

substrate with a valine at the P2 position which is

known to act as a substrate for Erv-C [17]. The kinetic

constants of the two recombinant enzymes (Table 1)

clearly show that rproErv-C

DCT

has almost 10 times

97 kDa

66 kDa

66 kDa

45 kDa

36 kDa

29 kDa

24 kDa

20 kDa

43 kDa rproErv-C+CT

rproErv-C+CT

rproErv-C∆CT

rmErv-C+CT

rmErv-C∆CT

rproErv-C∆CT

rmErv-C∆CT

rmErv-C+CT

29 kDa

20 kDa

M

1123

2

45 30 20 10 0 C25 15 5 M4530 20 10 0 C25 15 5

A

BC

Fig. 2. (A) Time course of activation to the mature form. (I) rproErv-C

+CT

. (II) rproErv-C

DCT

as discussed in Materials and methods. Time

intervals of 0–45 min are indicated for the respective lanes. Untreated proteins (control) are labelled as ‘C’, ‘M’ denotes the molecular mass

marker. (B) Gelatin gel assay of activated rproErv-C

DCT

(lane 1) and rproErv-C

+CT

(lane 2). (C) Western blot analysis. Lane 1, Erv-C purified

from the plant latex; lanes 2 and 3, purified and refolded rproErv-C

+CT

and rproErv-C

DCT

. [Correction added on 26 July 2011 after original

online publication: in the figure, labelling for part C was changed from ‘rproErv-C

+CT

, rproErv-C

DCT

, rproErv-C

+CT

and rproErv-C

DCT

to rproErv-C

+CT

,

rproErv-C

DCT

, rmErv-C

+CT

and rmErv-C

DCT

’].

S. Dutta et al. Role of C-terminal extension in a cysteine protease

FEBS Journal 278 (2011) 3012–3024 ª2011 The Authors Journal compilation ª2011 FEBS 3015

higher activity than rproErv-C

+CT

. One can probably

conclude that the CT-extension has some inhibitory

effect on the activity of the enzyme against a small

peptide.

Thermal stability

Temperatures of maximum proteolytic activity (T

max

)

for rproErv-C

+CT

and rproErv-C

DCT

are 50 and 45 C

(Table 2 and Fig. 4) and they retain > 90% activity

up to 65 and 60 C, respectively. These data indicate a

good thermotolerance for these enzymes. The pattern

of retention and fall in activity beyond T

max

was more

or less the same for both enzymes. The T

50

values for

rproErv-C

+CT

and rproErv-C

DCT

were 76 and 72 C

(Fig. 4), respectively. The half lives (t

1⁄2

)at65C were

400 min (Fig. 5) for both enzymes.

Molecular modeling studies

To gain insight into the stability and dynamic proper-

ties of the structure, solvent MD simulation was

110

100

rproErv-C+CT

rproErv-C∆CT

90

80

70

60

Residual activity (%)

Temperature (°C)

50

40

30

20

10

0

30 35 40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90 10095

Fig. 3. Determination of optimum temperature of activity (T

opt

)of

rproErv-C

+CT

and rproErv-C

DCT

. Purified proenzymes (10–20 lg)

were converted to their respective mature forms and the percent-

age residual enzyme activities were determined with respect to the

maximum activity using an azocasein assay at different tempera-

tures, as described in Materials and methods. Each data point is an

average of three independent experiments having similar values

(Table S3).

Table 1. Kinetic constants using the substrate N-benzoyl-Phe-Val-Arg-pNA. Specific activity using azocaesin and IC

50

value for the inhibitor

E-64. ND, not determined.

k

cat

(s

)1

)

a

K

m

(lM)

a

k

cat

⁄K

m

(s

)1

ÆmM

)1

)

Specific activity

at 37 C

b

(UÆmg

)1

)

Specific activity

at 65 C

b

(UÆmg

)1

)

IC

50

against

E-64 (nM)

c

rproErv-C

+CT

0.0170 ± 0.004 88.33 ± 56.77 0.193 No activity 15.87 ± 1.36 482.5 ± 108.0

rproErv-C

DCT

0.2295 ± 0.057 127.3 ± 48.46 1.803 13.21 ± 2.32 35.27 ± 1.78 349.1 ± 62.0

Latex Erv-C [17] 9.312 1063 8.76 75.0 ND 225.0

a

Given standard errors were calculated based on nonlinear fitting of the Michaelis–Menten saturation curve using the software Graphpad

PRISM (http://www.graphpad.com/prism).

b

Each value of specific activity of rproErv-C+CT and rproErv-CDCT is a mean of three independent

experiments ± SD.

c

Given standard deviations were calculated from linear regression plot of residual activity and inhibitor concentration.

Table 2. Kinetic stabilities. ND, not determined.

T

max

(C) T

50

(C)

t

1⁄2

at

65 C (min) T

opt

(C)

rproErv-C

+CT

(activity at 65 C)

50 76 400 65

rproErv-C

DC

(activity at 65 C)

45 72 400 65–70

Native mature Erv-C

(latex) [14,32]

70 76 ND 50

100

rproErv-C+CT

rproErv-C∆CT

80

60

Residual activity (%)

Temperature (°C)

40

20

0

40 45 50 55 60 65 70 75 80 85 90

Fig. 4. Effect of temperature on activity of rproErv-C

+CT

and rpr-

oErv-C

DCT

. Each purified proenzyme (10–20 lg) was treated for

10 min at different temperatures followed by activation of the pro-

proteins to their respective mature forms. The percentage residual

enzyme activities (at each temperature) were determined with

respect to the maximum activity using an azocasein assay at 65 C

as described in Materials and methods. Each data point is an aver-

age of three independent experiments having similar values

(Table S3).

Role of C-terminal extension in a cysteine protease S. Dutta et al.

3016 FEBS Journal 278 (2011) 3012–3024 ª2011 The Authors Journal compilation ª2011 FEBS