MINIREVIEW

Evolutionary changes to transthyretin: developmentally

regulated and tissue-specific gene expression

Kiyoshi Yamauchi and Akinori Ishihara

Department of Biological Science, Faculty of Science, Shizuoka University, Japan

Introduction

Thyroid hormones (THs) are lipophilic hormones that

modulate growth and development. As such, and to

ensure the distribution of adequate amounts of THs to

target tissues, most THs in blood are bound to specific

carrier proteins. In large eutherians, the major TH-car-

rier proteins are thyroxine-binding globulin (TBG),

transthyretin and albumin [1], which are synthesized in

the liver and then secreted into the bloodstream. The

TH-carrier proteins form the TH distribution network

[2] that maintains a pool of THs in the bloodstream

and facilitates the uniform distribution of THs to

target cells. The TH distribution network, in part, is

functionally redundant. This assumption is derived

from the observations that transthyretin-null mice and

patients with albumin and TBG deficiencies are euthy-

roid [2]. If the TH distribution network lacks one

TH-carrier protein, the remaining proteins maintain

the uniform distribution of THs to target cells.

The composition of the TH distribution network dif-

fers among species. TBG has been detected in the

plasma of juvenile and adult large eutherians, rodents

and some marsupials at postnatal or pouch stages [3].

However, the presence of TBG in the plasma of

lower vertebrates has not been reported. By contrast,

Keywords

developmental regulation; thyroid hormone;

tissue specificity; transcriptional control;

transthyretin

Correspondence

K. Yamauchi, Department of Biological

Science, Faculty of Science, Shizuoka

University, Shizuoka 422-8529, Japan

Fax: +81 54 238 0986

Tel: +81 54 238 4777

E-mail: sbkyama@ipc.shizuoka.ac.jp

(Received 2 February 2009, revised 21 June

2009, accepted 21 July 2009)

doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07245.x

A survey of the expression of the transthyretin and thyroxine-binding glob-

ulin genes in various species during development provides clues as to how

the present thyroid hormone distribution network in extracellular compart-

ments developed during vertebrate evolution. Albumin may be the ‘oldest’

component of the thyroid hormone distribution network as it is found in

the plasma of all vertebrates investigated. Subsequent to albumin, transthy-

retin appeared as the second component in this network during the evolu-

tion of vertebrates. The strong expression of transthyretin genes in the liver

coincides with the presence of recognition site(s) for liver-enriched tran-

scription factors, such as HNF-3b(Foxa2), in the transthyretin promoter

regions of vertebrates. Finally, the addition of thyroxine-binding globulin

to this network occurred at postnatal stages in some marsupials and

rodents and in perinatal to adult stages in most eutherians. All vertebrates

have defined developmental stages when thyroid hormone-dependent tran-

sition from larval to juvenile forms occurs. The inclusion of transthyretin

and thyroxine-binding globulin in the thyroid hormone distribution

network may be correlated with the increased requirement of thyroid

hormones for thyroid hormone-dependent tissue remodeling during these

stages and ⁄or increased metabolism in thyroid hormone-target tissues with

the acquisition of homeothermy.

Abbreviations

C/EBP, CCAAT/enhancer binding protein; E, embryonic day; HNF, hepatic nuclear factor; P, postnatal day; TBG, thyroxin-binding globulin;

TH, thyroid hormone.

FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 5357–5366 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS 5357

transthyretin has been detected in the plasma of fetal

and adult eutherians, and of some marsupials and

birds, but has not been detected, or has been detected

only at low levels, in the plasma of adult reptiles,

amphibians and fish. In these species, the expression of

transthyretin is modulated in developmentally specific

and species-specific manners [3]. Albumin is common

to all vertebrates (from cyclostomes to mammals) that

have been investigated, suggesting that from an evolu-

tionary perspective, it is the oldest TH-carrier protein.

The TH-carrier proteins are predominantly synthe-

sized in the liver. Transthyretin is secreted from the

choroid plexus into the cerebrospinal fluid of adult

mammals, birds and reptiles, in which it is a predomi-

nant protein. Transthyretin is also expressed in other

tissues in various species (e.g. in the retina of rats, in

the pancreas of humans and rats, in the heart of devel-

oping chickens and in the visceral yolk sac of rats

during fetal development) [2]. Recent studies have sug-

gested that the extrahepatic expression of transthyretin

is more predominant in lower vertebrates than in

higher vertebrates [4].

In this minireview, from an evolutionary point of

view, we survey (a) the developmental and tissue-spe-

cific regulation of the expression of TH-carrier protein

genes, in particular transthyretin, in various vertebrates

and (b) candidates for transcription factors involved in

transthyretin gene expression in the liver and possible

cis-elements in the transthyretin promoter regions, and

demonstrate the close link between the high expression

of TH-carrier protein genes in the liver and develop-

mental stages when THs are absolutely required for

TH-dependent tissue remodelling in each vertebrate

group.

Regulation of transthyretin gene

expression during development

In this section of our article, we will discuss the regula-

tion of transthyretin gene expression during develop-

ment in rat, marsupials, chicken, reptiles, amphibians

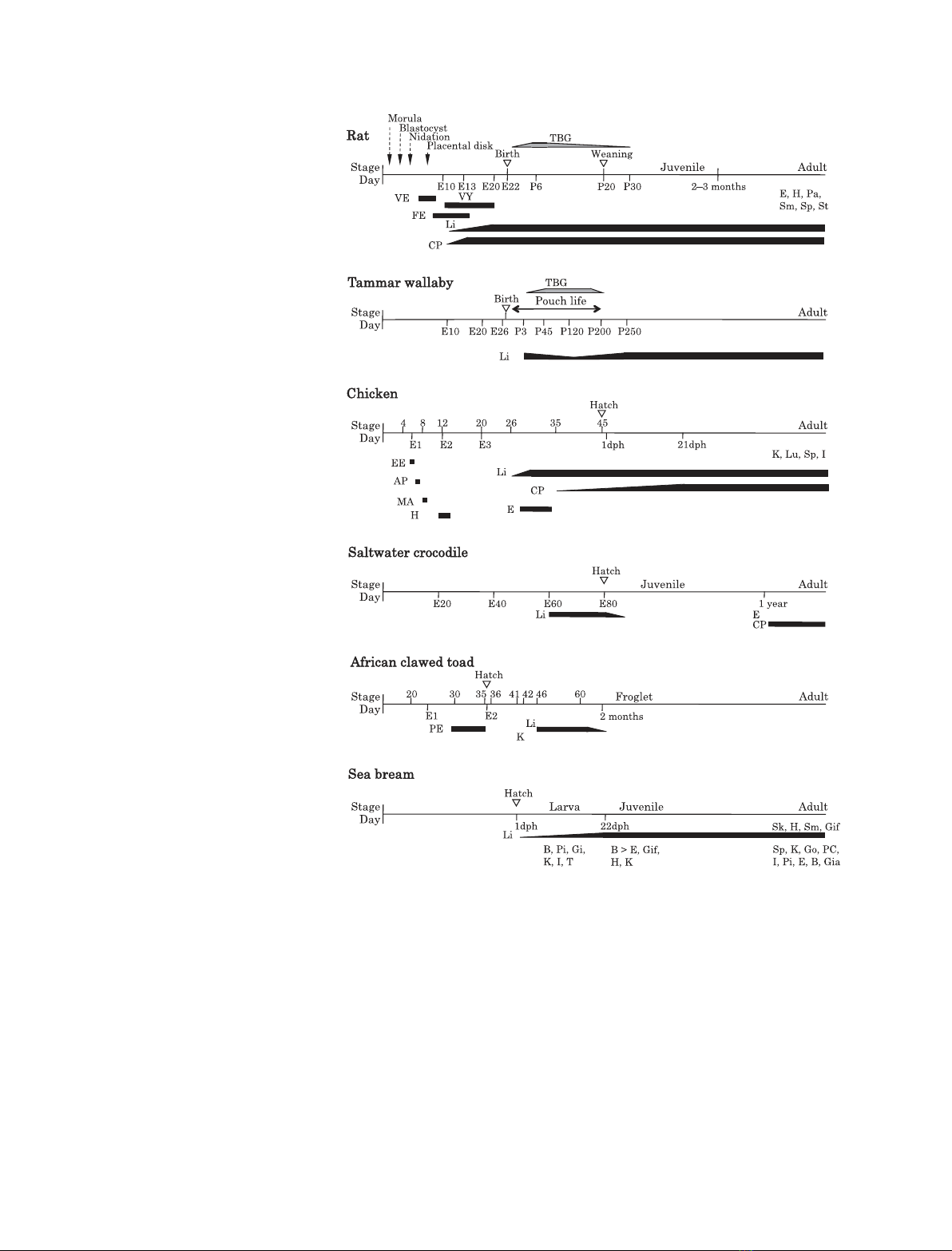

and fish (Fig. 1).

Rat

Transthyretin is expressed in extra-embryonic and

embryonic tissues during early embryogenesis, and its

expression is gradually confined to the liver and to the

choroid plexus during late embryogenesis. In rat

embryos, transthyretin transcripts were detected (by

in situ hybridization) in the visceral endoderm as early

as embryonic day (E) 7 [5]. At E9, the expression of

transthyretin was confined to the visceral extraembry-

onic endoderm and the foregut endoderm [5]. Trans-

thyretin transcripts were detected at increasingly higher

levels in the visceral yolk sac endoderm and in the fetal

liver from E10 to E13 [5], and throughout gestation

until birth (E14–E20) [6]. The expression of transthyre-

tin (detected using northern blot analysis) was rela-

tively higher in the visceral yolk sac than in the fetal

liver from E14 to E20 [6]. As the visceral yolk sac is

the site of true placentation in rodents, the expression

of transthyretin in the visceral yolk sac may assist the

transport and delivery of THs from the maternal blood

to the developing fetuses.

In other tissues of the developing rat, transthyretin

gene expression occurs in the brain when neuroepithe-

lial cells derived from the neural tube differentiate into

the epithelial cells of the choroid plexus in both the

hindbrain and forebrain. Transthyretin transcripts first

appear in the fourth ventricle at E12.5, in the lateral

ventricles at E13.5 and subsequently in the third ven-

tricle [7]. Transthyretin expression has also been

reported in the eye, heart, pancreas, skeletal muscle,

spleen and stomach in developing or adult rats [4,8].

Marsupials

The expression and synthesis of transthyretin in marsu-

pials is evident in the evolutionarily older polyproto-

dont marsupials, which inhabit America and Australia,

and in the recently diverged diprotodont marsupials,

which inhabit Australia [2]. In adult marsupials, trans-

thyretin was detected in the plasma from American

polyprotodont marsupials (e.g. Virginia opossum) and

Australian diprotodont marsupials (e.g. tammar wal-

laby, scaly-tailed possum and common wombat) but

not in the plasma from Australian polyprotodont mar-

supials (e.g. fat-tailed dunnart and Tasmanian devil),

even though albumin was detected in all marsupials

investigated [2,3,9,10]. Transthyretin gene expression

was observed in the choroid plexus of all adult mar-

supials studied, in the American and Australian

polyprotodonts (e.g. short-tailed grey opossum and

stripe-faced dunnart, respectively) and in an Australian

diprotodont (e.g. sugar glider) [11].

As a typical example, transthyretin gene expression

during development of the tammar wallaby (Macro-

pus eugenii, an Australian diprotodont marsupial) is

shown in Fig. 1. Transthyretin transcripts were

detected in the liver during pouch life [postnatal day

(P) 3 to P200], when the young animal does not have a

mature thyroid gland and obtains THs from its

mother’s milk. Transthyretin expression in the liver

continues through pouch life to adulthood [12]. This

was confirmed by binding studies of [

125

I]thyroxine

Transthyretin gene expression during development K. Yamauchi and A. Ishihara

5358 FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 5357–5366 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS

with blood plasma [12]. However, in the fat-tailed

dunnart (an Australian polyprotodont marsupial),

transthyretin was detected in plasma during a defined

developmental stage of pouch life, from P27 to P62 [3].

This defined developmental stage corresponds to that

in the young tammar wallaby during which thyroxine-

binding protein was detected in plasma [3].

Chicken

Transthyretin is known to accumulate in oocytes from

the circulation [13]. THs also accumulate in the yolk

during oogenesis. As THs are necessary for normal

embryonic development, these observations suggest

that before the vascular system and the hypothalamic–

pituitary–thyroid axis are established, transthyretin

plays a role in the transport and distribution of THs

from the yolk to specific embryonic sites.

Transthyretin may have a role in heart development

in the chicken as it was identified as one of the main

proteins secreted from cultured anterior lateral endo-

derm (which may play a part in cardiogenesis), in the

chick embryo at E1.5–E3.5 (corresponding to stages

3–21) before the onset of vascular system development

Fig. 1. Developmentally regulated transthy-

retin expression profile in various verte-

brates. Developmental windows and tissues

of various vertebrates in which transthyretin

expression has been reported, are summa-

rized with those for TBG. Data are from in

the rat (Rattus norvegicus) [5–8,55], marsu-

pial [tammar wallaby (Macropus eugenii)]

[3,12], chicken (Gallus gallus) [14–16], reptile

[saltwater crocodile (Crocodylus porosus)]

[3,20], frog [African clawed toad (Xeno-

pus laevis)] [25] and fish [sea bream (Spa-

rus aurata)] [4,26,27]. Black and gray bars

represent the developmental stages or peri-

ods during which transthyretin or its tran-

scripts, and TBG or its transcripts, are

detected, respectively. In this figure, the

ages at weaning in eutherians, initial pouch

exit in marsupials, at hatch in birds and rep-

tiles, completion of metamorphosis in

amphibians and transition of larva to juvenile

in fish are adjusted as a period of postem-

bryonic transformation in vertebrates. The

day of development: E, embryonic day; P,

postnatal day; dph, day post-hatch. AP,

anterolateral portion of embryo; CP, choroid

plexus; EE, extraembryonic endoderm; FE,

foregut endoderm; MA, midline in the ante-

rior half of embryo; PC, pyloric cacea; PE,

posterior endoderm; VE, visceral endoderm;

VY, visceral yolk sac; B, brain; E, eye; Gi,

gill; Gia, gill arch; Gif, gill filaments; Go,

gonad; H, heart muscle; I, intestine; K,

kidney; Li, liver; Lu, lung; Pa, pancreas; Pi,

pituitary; Sp, spleen; Sk, skin; Sm, skeletal

muscle; St, stomach; T, testis.

K. Yamauchi and A. Ishihara Transthyretin gene expression during development

FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 5357–5366 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS 5359

[14]. This transthyretin is not of maternal origin

and is synthesized de novo in the embryo. In situ

hybridization located transthyretin transcripts to the

extraembryonic endoderm at E1.0 (stage 6), to the

anterolateral portion of the embryo proper at E1.0–

E1.1 (stage 7) and near the midline in the anterior half

of the embryo at E1.1–E1.4 (stages 8–9). At E1.8–E2.1

(stages 11–14), transthyretin transcripts were also

detected in myocardial cells of the definitive heart.

During later developmental stages in chicks, the

main sites of transthyretin expression are the choroid

plexus and the liver. The amount of transthyretin tran-

scripts in the choroid plexus increased gradually from

E9 (stage 35) to 3 weeks after hatching [15]. By con-

trast, the amount of transthyretin transcripts in the

liver increased to adult levels by E7 (stage 30). At E6

and E8 (stages 28–29 and 33–34), transthyretin expres-

sion was also detected (by northern blot analysis) in

the eye, but not in the intestine and lung [15]. In adult

chickens, transthyretin gene expression was detected

(by RT-PCR) in the kidney, lung, spleen and intestine

[16]. Transthyretin expression was also observed in the

choroid plexus and liver of adult ducks, quails and

pigeons [15].

Reptiles

Transthyretin was first detected in reptiles by culturing

choroid plexus dissected from the Australian stumpy-

tailed lizards (Tiliqua rugosa) with [

14

C]leucine,

followed by analyses using SDS ⁄PAGE and fluorogra-

phy [17]. Interestingly, transthyretin transcripts were

detected (by northern blot analysis) in the choroid

plexus, but not in the liver, of adult lizards [18], and

were detected (by RT-PCR) in the eye and kidney, but

not in the liver [18]. Transthyretin was found to be

highly expressed in the choroid plexus of the turtle

(Trachemys scripta) [19] and the juvenile saltwater croc-

odile (Crocodylus porosus) [20]. By contrast, only small

amounts of transthyretin transcripts were detected in

the liver, and none in the kidney, of the turtles. In the

crocodiles, the second major expression site of the

transthyretin gene was the eye. Transthyretin tran-

scripts were not detected in the heart and liver of the

crocodiles. Recently, transthyretin was detected in the

plasma from embryonic saltwater crocodiles before and

at hatching (E60 to 1 day after hatching), but not in

plasma from juvenile or adult saltwater crocodiles [3].

Amphibians

During early development of amphibians, transthyretin

is expressed in embryonic endoderm. Transthyretin

gene expression was investigated as a tissue marker of

the differentiating liver in the African clawed toad,

Xenopus laevis, during embryonic development by

whole-mount in situ hybridization and RT-PCR

[21,22]. Transthyretin transcripts were expressed in a

more posterior stripe of endoderm (intestine) but not

the liver diverticulum of the tail bud embryo at E1.5

(stages 30–35) [21,22]. Initially, the expression of the

transthyretin transcripts was widespread and included

the mesoderm of the kidney, at E3 (stages 41–42), but

was gradually restricted to the liver by E7 (stages 46–

47) [21]. According to the expression characteristics,

genes for embryonic endoderm development in X.la-

evis were categorized into four groups: (a) the liver-

specific group, (b) the liver and intestine group A, (c)

the liver and intestine group B and (d) the intestine-

specific group [22]. Expression of genes in the liver and

intestine group A are required for the continuous and

specific cell–cell interactions of the endoderm and

includes the transthyretin gene.

During metamorphosis, the predominant site of

transthyretin expression is the liver. Transthyretin gene

expression was detected (by in situ hybridization) in

the liver but not in the choroid plexus of the American

bullfrog, Rana catesbeiana, from premetamorphic to

prometamorphic stages [23]. These stages correspond

to the point in time when the concentrations of TH in

plasma increase and reach maximum levels [24]. How-

ever, transthyretin transcript levels decreased gradually

during the metamorphic climax stages in X.laevis [25]

and R.catesbeiana [23]. Transthyretin transcripts have

not been detected (by northern blot analysis) in adult

tissues of either species.

Fish

During the development of fish, transthyretin is

expressed in the liver. Transthyretin was first detected

in juvenile fish: the sea bream Sparus aurata [26, 27],

and in smolting masu salmon Oncorhynchus masou [28].

In the sea bream, transthyretin transcripts were

expressed in hatching larvae as early as 1 day post-

hatch (48 h after fertilization). The expression of

transthyretin transcripts in the whole body of larva

increased gradually during development (from 1 day

post-hatch to 22 days post-hatch) [27]. RT-PCR

demonstrated that the transthyretin transcripts were

expressed predominantly in the liver of the sea bream

larvae, with low levels of expression found in the brain,

pituitary, gills, kidney, intestine and testis [26].The

amounts of transthyretin transcripts in tissues from the

sea bream fingerling were greatest in the liver, followed

by the brain, then the eye, gill filaments, heart and

Transthyretin gene expression during development K. Yamauchi and A. Ishihara

5360 FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 5357–5366 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS

kidney [27]. In adult sea breams, the major site of

expression of the transthyretin transcripts was the liver.

Transthyretin was also expressed at moderate levels in

the skin, heart, muscle and gill filaments, with minor

expression found in the spleen, kidney, gonad, pyloric

cacea, intestine, pituitary, eye, brain and gill arch [27].

Expression of the transthyretin gene in the liver dur-

ing smoltification in salmonid fish may facilitate the

transition of the freshwater dwelling parr into a smolt

adapted to the life in salt water. In the masu salmon,

transthyretin was purified from plasma obtained dur-

ing smoltification [28] when the plasma concentrations

of endogenous THs are highest. Transthyretin was also

detected in the plasma from smolting Atlantic salmon

Salmo salar and the Chinook salmon Onchorhyn-

chus tshawytscha [3].

Recently, transthyretin cDNAs were cloned from the

livers of the Pacific bluefin tuna Thunnus orientalis [29]

and from the livers of two genera of the lampreys

Petromyzon marinus and Lampetra appendix [30].

Transthyretin transcripts were detected in the liver of

1-year-old bluefin tuna, concomitant with the ovary

but not the testis. The amount of transthyretin tran-

scripts in the liver of 3-year-old bluefin tuna was less

than that in the liver of 1-year-old bluefin tuna. Trans-

thyretin transcripts were not detected in the ovaries of

sexually mature 3-year-old female bluefin tuna [29]. In

the lamprey larvae, transthyretin transcripts were

detected predominantly in the liver, with low levels of

expression in the gill, brain, heart, gut, kidney and

blood [30]. The expression of transthyretin reached a

maximum level in the liver during metamorphosis

when serum TH levels are at their lowest. In lamprey,

in contrast to the bony fish (such as flatfish) and

amphibians, the onset of metamorphosis is triggered

by a decrease in circulating TH levels. The role of TH

receptors in controlling metamorphosis must be differ-

ent in lamprey than in other vertebrates.

Control of transthyretin gene

expression

Analysis of the transthyretin promoter in mice

The upstream regulatory region of the mouse transthy-

retin gene has been investigated extensively as a model

for understanding gene expression in the liver. The

proximal region of the transthyretin promoter and a

distal enhancer are sufficient for transthyretin gene

expression in the liver, but not in the choroid plexus

[31]. These regions, as well as the regulatory regions of

other genes in the liver such as albumin, a1-antitrypsin

and a-fetoprotein, contain several recognition sites for

liver-enriched transcription factors including hepatic

nuclear factor-4 (HNF-4), three distinct HNF-3 pro-

teins (a,band c; recently renamed Foxa1, Foxa2 and

Foxa3), HNF-1 and CCAAT/enhancer binding protein

(C ⁄EBP) [32,33]. A combination of transcription

factors acting on multiple recognition sites in the

upstream regulatory region of the transthyretin gene is

required for the activation and maintenance of its tran-

scription in the liver. Of these transcription factors,

HNF-3 proteins are essential for transthyretin expres-

sion in human hepatoma HepG2 cells. HNF-3 proteins

belong to a family of transcription factors that are

homologous to the winged helix ⁄forkhead DNA-bind-

ing domain and have important roles in cellular

proliferation and differentiation during embryonic

development. Studies using retinoic acid-induced dif-

ferentiation of mouse F9 embryonal carcinoma cells

revealed that HNF-3a(Foxa1) is a primary target for

retinoic acid action. Activation of HNF-3ainduced

the transcription of HNF-3b(Foxa2), which was fol-

lowed by an increase in the expression of transthyretin,

Sonic hedgehog, HNF-1a, HNF-1band HNF-4agenes

during the differentiation of F9 cells to the visceral

endoderm lineage [34].

Possible recognition sites for liver-enriched

transcription factors in the transthyretin

promoters from various vertebrates

Figure 2A shows the possible recognition sites for

HNF-1, HNF-3band HNF-4 in the 0.2-kbp promoter

regions of transthyretin genes from various species.

The tetrapods [human, rat, chicken and frog (Sil-

urana tropicalis)] have more than one HNF-3bsite –

H3(+) and H3()) – in the promoter regions of the

transthyretin genes. By contrast, the fish (Taki-

fugu rubripes) transthyretin gene has no HNF-3bsite

in the promoter region. Human, rat, frog (Sil-

urana tropicalis) and fish (Takifugu rubripes) have one

HNF-1 site, H1(+), in the promoter regions. Human,

rat, frog (Silurana tropicalis) and fish (Takifugu rub-

ripes), but not chicken, have one HNF-4 site, H4(+).

Of these recognition sites, H3()) (eight of twelve nucle-

otides) and H1(+) (ten of thirteen nucleotides) are the

most conserved throughout vertebrate evolution in

these animals (Fig. 2B). The fish transthyretin gene

may have a distinct promoter for the recognition of

transcription factors, especially HNF-3b, compared

with the transthyretin promoters of other vertebrates.

Prevalent expression of transthyretin in tissues other

than liver of the sea bream [26,27], Pacific bluefin tuna

[29] and lamprey [30] may reflect the unique structure

of the fish transthyretin promoter.

K. Yamauchi and A. Ishihara Transthyretin gene expression during development

FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 5357–5366 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS 5361