MINIREVIEW

Regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity

in plant cells

Alejandro Tovar-Me

´ndez

1

, Jan A. Miernyk

1,2

and Douglas D. Randall

1

1

Department of Biochemistry, University of Missouri, Columbia, USA;

2

Plant Genetics Research Unit, USDA,

Agricultural Research Service, Columbia, USA

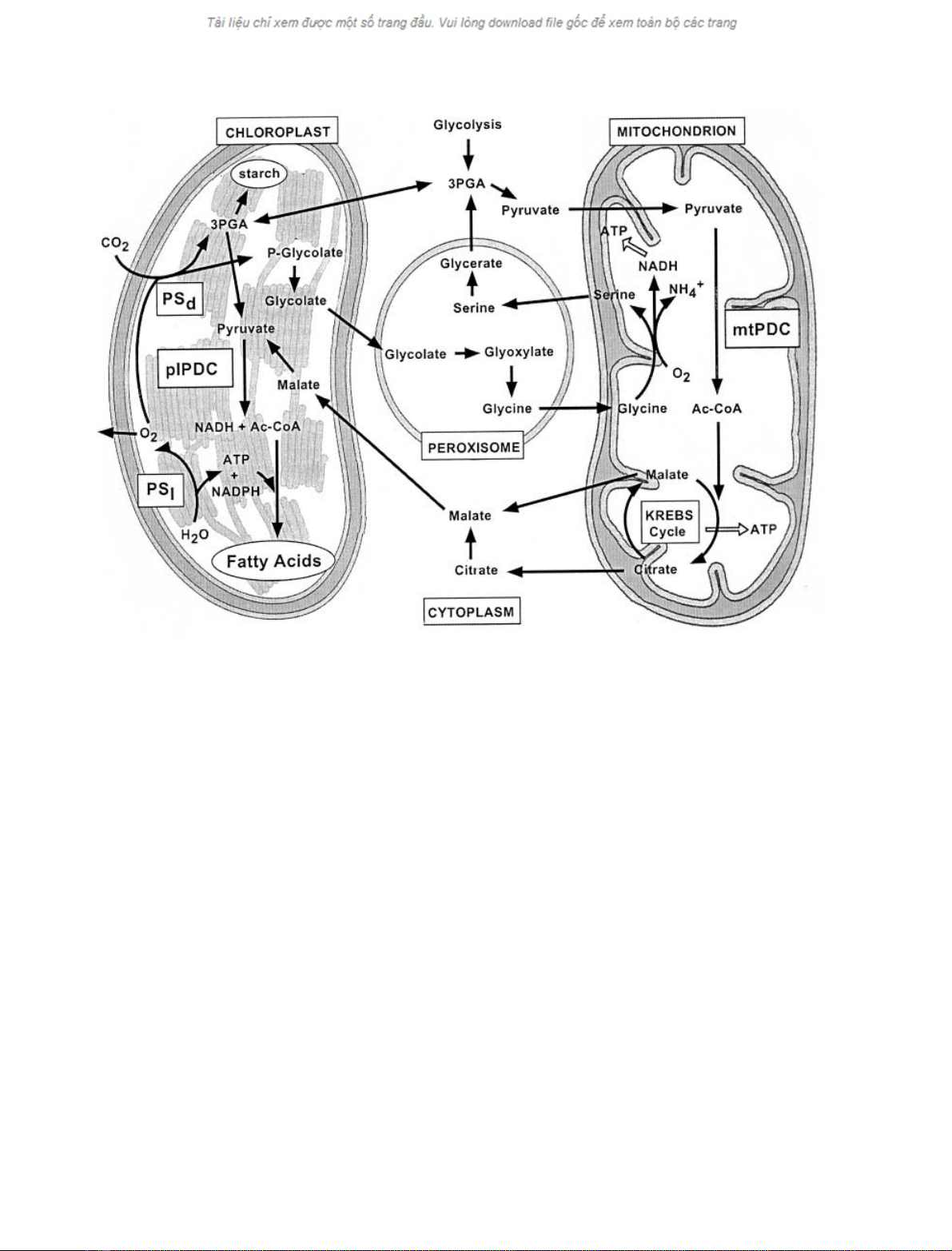

The pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) is subjected to

multiple interacting levels of control in plant cells. The first

level is subcellular compartmentation. Plant cells are unique

in having two distinct, spatially separated forms of the PDC;

mitochondrial (mtPDC) and plastidial (plPDC). The

mtPDC is the site of carbon entry into the tricarboxylic acid

cycle, while the plPDC provides acetyl-CoA and NADH for

de novo fatty acid biosynthesis. The second level of regula-

tion of PDC activity is the control of gene expression. The

genes encoding the subunits of the mt- and plPDCs are

expressed following developmental programs, and are

additionally subject to physiological and environmental

cues. Thirdly, both the mt- and plPDCs are sensitive to

product inhibition, and, potentially, to metabolite effectors.

Finally, the two different forms of the complex are regulated

by distinct organelle-specific mechanisms. Activity of the

mtPDC is regulated by reversible phosphorylation catalyzed

by intrinsic kinase and phosphatase components. An addi-

tional level of sensitivity is provided by metabolite control of

the kinase activity. The plPDC is not regulated by reversible

phosphorylation. Instead, activity is controlled to a large

extent by the physical environment that exists in the plastid

stroma.

Keywords: complex; chloroplast; enzymology; localization;

metabolic regulation; mitochondria; phosphorylation.

Introduction

The pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) is a multien-

zyme complex catalyzing the oxidative decarboxylation of

pyruvate to yield acetyl-CoA and NADH. The plant PDCs

occupy strategic and overlapping positions in plant cata-

bolic and anabolic metabolism (Fig. 1). Similar to other

PDCs, the plant complexes contain three primary compo-

nents: pyruvate dehydrogenase (E1), dihydrolipoyl acetyl-

transferase (E2) and dihydrolipoyl dehydrogenase (E3). In

addition, mitochondrial PDC (mtPDC) has two associated

regulatory enzymes: pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase (PDK)

and phospho-pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase (PDP).

Here we briefly describe our current understanding of the

regulation of PDC activity in plant cells. Detailed descrip-

tions of the plant complexes are provided by more

comprehensive reviews [1–3].

Compartmentation of the PDC

It is widely believed that eukaryotic cells arose as the result

of phagotrophic capture of bacteria and subsequent sym-

biotic association. The progenitors of mitochondria are

thought to be a-proteobacteria [4], possibly related to

contemporary Rickettsia [5]. The plastids that are charac-

teristic of plant cells are thought to have been derived from a

single common primary symbiotic event with a cyanobac-

terium [6]. Subsequently, there was extensive gene migration

to the nucleus leaving both mitochondria and plastids as

semiautonomous organelles. Most mitochondrial and plas-

tidial proteins, including the subunits of the PDC, are

encoded within the nuclear genome of land plants, synthes-

ized in the cytoplasm and then post-translationally imported

into the organelles [3]. In nonplant eukaryotes the PDC is

exclusively localized within the mitochondrial matrix, and

serves as an entry point for carbon into the Krebs cycle. The

regulatory properties of mtPDC have been specialized to

minimize activity in an environment where ATP levels are

high. Plant cells contain an mtPDC that is closely related to

those of animal cells, but additionally contain a plastidial

form of the PDC (plPDC, Fig. 1) that is more closely

related to the PDC from cyanobacteria [3,7]. In contrast to

mtPDC, the regulatory properties of plPDC are specialized

to minimize the effects of an environment with high levels of

ATP. The physical environment within the chloroplast

stroma changes markedly during the light/dark transition,

and specialized regulatory mechanisms have evolved for

control of plPDC activity in the dark.

Mature plastids differentiate from proplastid progenitors

to serve specialized functions in different plant organs.

Plastid terminology is largely based upon pigmentation,

Correspondence to J. A. Miernyk, USDA/ARS, Plant Genetics

Research Unit, 108 Curtis Hall, University of Missouri,

Columbia, MO 65211, USA.

Fax: + 1 573 884 7850, Tel.: + 1 573 882 8167,

E-mail: miernykj@missouri.edu

Abbreviations: PDC, pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; mtPDC,

mitochondrial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; plPDC,

plastidial pyruvate dehydrogenase complex; E1, pyruvate dehydro-

genase; E2, dihydrolipoyl acetyltransferase; and E3, dihydrolipoyl

dehydrogenase; PDP, phospho-pyruvate dehydrogenase phosphatase.

(Received 13 September 2002, accepted 29 November 2002)

Eur. J. Biochem. 270, 1043–1049 (2003) ÓFEBS 2003 doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03469.x

with leucoplasts, etioplasts, chloroplasts and chromoplasts

being, respectively, unpigmented, pale yellow, green and

red/orange. The chlorophyll-containing green plastids

(chloroplasts) are the site of photosynthesis in autotrophic

plant cells. Plastids, regardless of pigmentation or degree of

differentiation, are the sole site of de novo fatty acid

biosynthesis in plant cells [8]. All forms of plastids contain

the plPDC, which provides the acetyl-CoA and NADH

necessary for fatty acid biosynthesis [9].

Recently it has been discovered that certain animal cell

parasites, such as Plasmodium spp., contain a type of

nonphotosynthetic plastid termed the apicoplast [10]. Pos-

sibly this type of plastid originated from an endosymbiotic

event involving a red algal cell. The fragmentary informa-

tion available indicates that red algal plPDCs are more

closely related to other plPDCs than to any mtPDC [3,7].

There is as yet no sequence information concerning red algal

mtPDC or plasmodial PDCs, but when this becomes

available it should provide us with additional phylogenetic,

evolutionary and regulatory insights.

Plastidial PDC

Based upon the results of cell-fractionation, it was proposed

that developing oilseeds contain a plastidial glycolytic

pathway in addition to the classical cytoplasmic glycolysis

[11]. It was additionally reported that these same plastids

contain a unique form of the PDC [12–14]. The plPDC from

developing castor endosperm has the same kinetic mechan-

ism as mtPDC, but has distinct catalytic and enzymatic

properties. It was later reported that green leaves from pea

seedlings also contain both mitochondrial and plastidial

forms of the PDC [15]. The occurrence of plPDC was briefly

controversial, however all of the subunits have now been

cloned [7,16,17] and their plastidial localization verified by

in vitro import studies [16,18] and confocal microscopy of

GFP-fusion proteins [19].

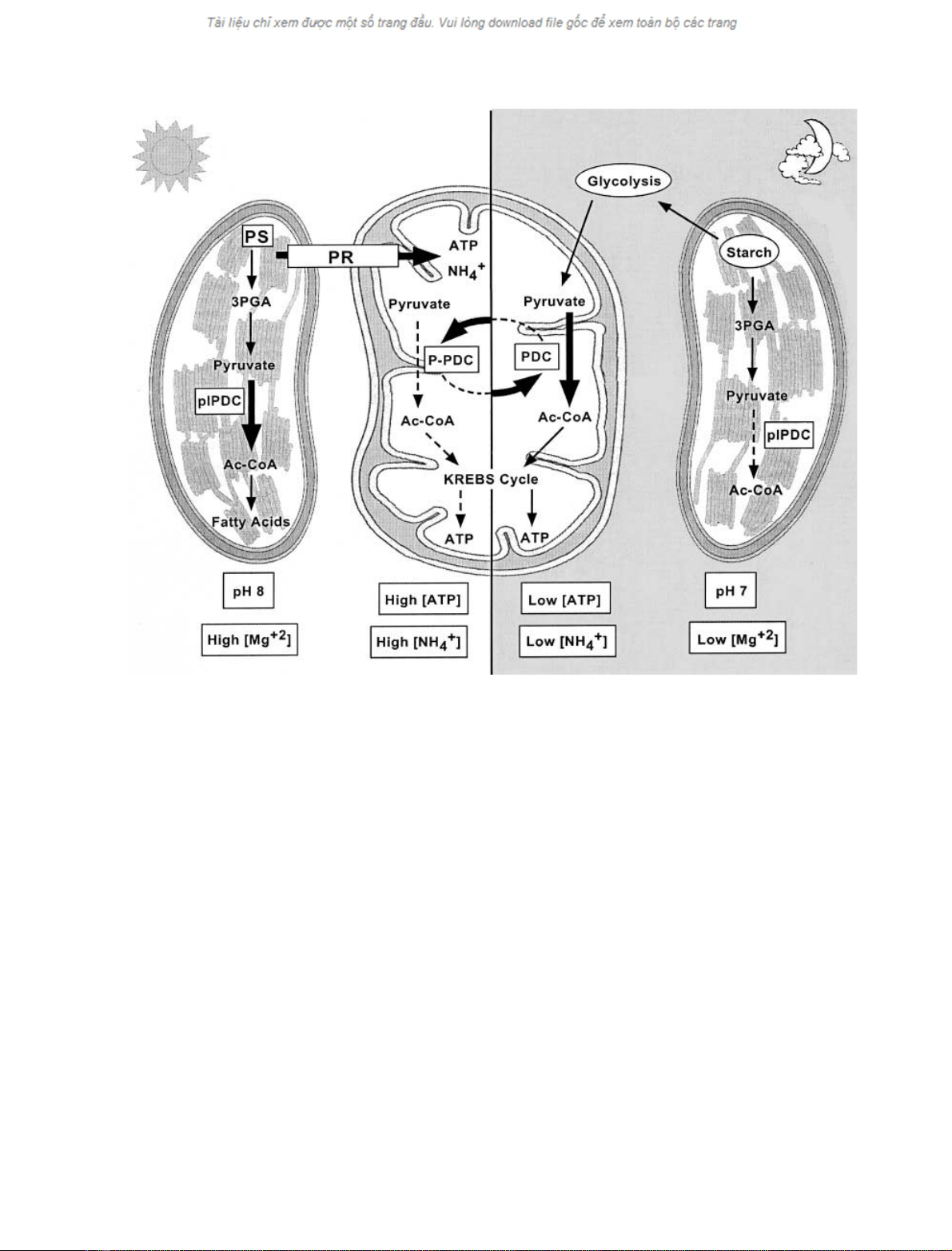

Similar to bacterial and mtPDC, the activity of plPDC is

sensitive to product inhibition by NADH and acetyl-CoA

[9,20]. Another property that is shared with bacterial PDCs

is that plPDC is not regulated by phosphorylation. Early

enzymatic studies of plPDC noted that the pH optimum

was significantly more alkaline than that of mtPDC, and

that higher Mg

2+

concentrations were necessary for maxi-

mal activity [9,12]. When plant leaves are shifted from dark

to light there is a rapid alkalinization of the chloroplast

stroma along with an increase in the free Mg

2+

concentra-

tion [21]. Both of these changes would activate plPDC.

De novo synthesis of fatty acids in green organs of plant cells

is light-driven and occurs exclusively within the plastids [8].

The plPDC provides acetyl-CoA and NADH for fatty acid

biosynthesis [9], so it is essential that PDC activity parallels

that of fatty acid biosynthesis. Thus, a unique mechanism

for regulating activity of plPDC activity has evolved based

Fig. 1. Compartmentalization of metabolism in plant cells. PS

l

, the light reactions of photosynthesis; PS

d

, the dark reactions of photosynthesis.

1044 A. Tovar-Me

´ndez et al.(Eur. J. Biochem. 270)ÓFEBS 2003

upon the physical conditions present in the chloroplast

stroma (Fig. 2). It is additionally possible that the activity of

plPDC [22] might be sensitive to light:dark changes in the

redox state of the chloroplast stroma [23] as are several

chloroplast regulatory enzymes [24].

Expression of plPDC

Expression of genes encoding the component enzymes of

plPDC is responsive to developmental and physiological

cues. The level of plE1bmRNA expressed in A. thaliana

siliques increased to a peak six to seven days after

flowering, then decreased with seed maturity [25]. This

pattern of developmental expression is parallel to that of

plastidial acetyl-CoA carboxylase, consistent with a role for

both enzymes in seed oil synthesis and accumulation [25].

The importance of plPDC in seed oil synthesis has been

further supported by results from both digital Northern

[26] and microarray [27] analyses of developing A. thaliana

seeds.

In addition to developing seeds, it has been reported that

there were high levels of expression of plE1b[25], plE2 [16],

and plE3 [17] in A. thaliana flowers. However, when the

b-glucuronidase (GUS) reporter gene was fused to the

A. thaliana plE3 promoter, and this chimera expressed in

tobacco plants, high levels of expression were seen in

developing seeds and mature pollen grains while low levels

were present in young leaves and flowers [19]. This result

suggests the previously reported elevated levels of plPDC

subunit expression in flowers might instead reflect mRNAs

present in the pollen.

Mitochondrial PDC

Product inhibition

As with their mammalian and microbial counterparts, plant

PDCs employ a multisite ping-pong kinetic mechanism. The

forward reaction is irreversible under physiological condi-

tions, but activity is sensitive to product inhibition by

NADH and acetyl-CoA. The K

i

values for NADH (20 l

M

)

and acetyl-CoA (20 l

M

) are within the physiological

concentration range [28]. While the results from in vitro

studies suggest that NAD

+

/NADH is the more important

regulator, results from analyses using isolated intact mito-

chondria suggest that acetyl-CoA/CoA can also have a

significant regulatory influence because of the small size of

the total CoA pool [29].

Fig. 2. Schematic overview of the regulation of pyruvate dehydrogenase complex activity in autotrophic plant cells. Distinct regulatory mechanisms

control the activity of mtPDC in the light and plPDC in the dark. PS, photosynthesis; PR, the photorespiratory pathway; PDC, the pyruvate

dehydrogenase complex; P-PDC, the phosphorylated (inactive) form of PDC.

ÓFEBS 2003 Regulation of PDC activity in plant cells (Eur. J. Biochem. 270) 1045