Stability and fibril formation properties of human and

fish transthyretin, and of the Escherichia coli

transthyretin-related protein

Erik Lundberg

1

, Anders Olofsson

2

, Gunilla T. Westermark

3

and A. Elisabeth Sauer-Eriksson

1

1 Department of Chemistry, Umea

˚University, Sweden

2 Department of Medical Biochemistry and Biophysics, Umea

˚University, Sweden

3 Division of Cell Biology, Diabetes Research Centre, Linko

¨ping University, Sweden

Transthyretin (TTR) is a homotetrameric plasma pro-

tein that binds and transports the thyroid hormones

3,5,3¢-triiodo-l-thyronine and 3,5,3¢,5¢-tetraiodo-l-thyr-

onine (thyroxine) and retinol by binding to the retinol-

binding protein when it is loaded with retinol [1]. TTR

is mainly expressed in the adult liver, the choroid

plexus of the brain, and the retina [2,3]. TTR is

involved in three amyloid diseases: familial amyloidotic

polyneuropathy, familial amyloidotic cardiomyopathy

(FAC), and senile systemic amyloidosis (SSA) [4,5].

Whereas SSA is associated with native TTR, point

mutations, of which more than 80 have been identified,

cause FAP and FAC [6]. TTR mutations associated

with familial amyloid diseases display a wide range of

Keywords

amyloid; fibril formation; HIU hydrolase;

transthyretin; transthyretin-related protein

Correspondence

A. E. Sauer-Eriksson, Department of

Chemistry, Umea

˚University, SE-90187

Umea

˚, Sweden

Fax: +46 90 7865944

Tel: +46 90 7865923

E-mail: elisabeth.sauer-eriksson@chem.

umu.se

(Received 7 November 2008, revised 20

January 2009, accepted 26 January 2009)

doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.06936.x

Human transthyretin (hTTR) is one of several proteins known to cause

amyloid disease. Conformational changes in its native structure result in

aggregation of the protein, leading to insoluble amyloid fibrils. The trans-

thyretin (TTR)-related proteins comprise a protein family of 5-hydroxyiso-

urate hydrolases with structural similarity to TTR. In this study, we tested

the amyloidogenic properties, if any, of sea bream TTR (sbTTR) and

Escherichia coli transthyretin-related protein (ecTRP), which share 52%

and 30% sequence identity, respectively, with hTTR. We obtained filamen-

tous structures from all three proteins under various conditions, but, inter-

estingly, different structures displayed different tinctorial properties. hTTR

and sbTTR formed thin, curved fibrils at low pH (pH 2–3) that bound

thioflavin-T (thioflavin-T-positive) but did not stain with Congo Red (CR)

(CR-negative). Aggregates formed at the slightly higher pH of 4.0–5.5 had

different morphology, displaying predominantly amorphous structures.

CR-positive material of hTTR was found in this material, in agreement

with previous results. ecTRP remained soluble at pH 2–12 at ambient tem-

peratures. By raising of the temperature, fibril formation could be induced

at neutral pH in all three proteins. Most of these temperature-induced

fibrils were thicker and straighter than the in vitro fibrils seen at low pH.

In other words, the temperature-induced fibrils were more similar to fibrils

seen in vivo. The melting temperature of ecTRP was 66.7 C. This is

approximately 30 C lower than the melting temperatures of sbTTR

and hTTR. Information from the crystal structures was used to identify

possible explanations for the reduced thermostability of ecTRP.

Abbreviations

AFM, atomic force microscopy; BME, b-mercaptoethanol; CR, Congo Red; DSC, differential scanning calorimetry; ecTRP, Escherichia coli

transthyretin-related protein; EM, electron microscopy; FAC, familial amyloidotic cardiomyopathy; hTTR, human transthyretin; rTTR, rat

transthyretin; sbTTR, sea bream transthyretin; SSA, senile systemic amyloidosis; ThT, thioflavin-T; TLP, transthyretin-like protein; TRP,

transthyretin-related protein; TTR, transthyretin.

FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 1999–2011 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS 1999

diversity in age of onset, penetrance, and tissues affected

[7,8]. SSA is a geriatric disease affecting approximately

25% of the European Caucasian population over

80 years of age [4]. Like FAC, SSA is characterized by

heavy deposits of amyloid fibrils in the heart.

Structures of TTRs from different species have been

studied [9], including human transthyretin (hTTR)

[10–12], rat TTR (rTTR) [13], chicken TTR [14], and sea

bream TTR (sbTTR) [15,16]. Within the TTR family,

fish TTR has the lowest sequence identity with hTTR

(e.g. sbTTR 52% [16,17], and lamprey TTR 47% [18]).

The transthyretin-related proteins (TRPs) comprise

a family of proteins recently shown to function as

5-hydroxyisourate hydrolases in the purine degradation

pathway [19–23]. These proteins are also referred to in

the literature as transthyretin-like proteins (TLPs).

However, to separate this family, whose members have

the characteristic sequence motif YRGS at their C-ter-

minal end, from other protein sequences listed as

TTR-like, we prefer to refer to them as TRPs [19,24].

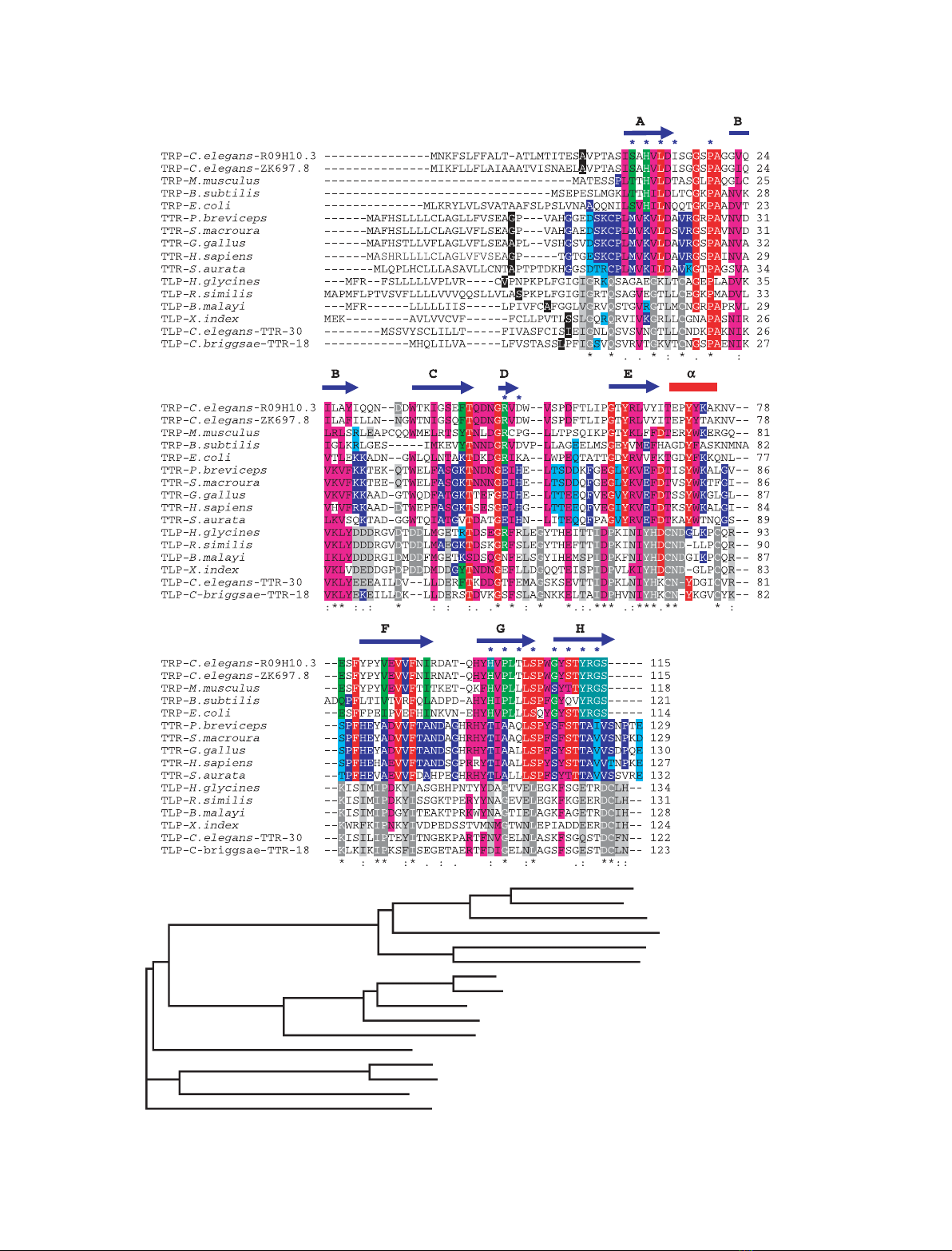

Sequence analysis of representative TTRs, TRPs and

TLPs suggests that the three protein groups are not

functionally related (Fig. 1).

The sequence identity between TRPs and TTRs is

relatively low; Escherichia coli TRP (ecTRP) shares

30% and 35% sequence identity with hTTR and

sbTTR, respectively (Fig. 1) [19]. Structures of TRP

from several species have been determined, and despite

their low sequence identity, the TTR and TRP struc-

tures were found to be very similar [24–27].

In TTR amyloidoses, the normally folded, secreted

protein cannot assemble into amyloid fibrils unless a

preceding partial unfolding event occurs [28]. Muta-

tions that destabilize the native structure of TTR are

known to lead to disease [29], but thermodynamic

stability alone does not reliably predict the severity of

the disease [30]. Instead, thermodynamic data,

combined with kinetic data, more reliably explain why

only some mutations lead to severe pathologies [31].

To understand the mechanism behind hTTR dissoci-

ation, misfolding, and amyloid formation, studies from

other species have provided valuable information. Like

hTTR, rTTR forms amyloid-like fibrils in vitro after

partial acid denaturation [32]. rTTR shares 85%

sequence identity with hTTR, which raises the question

of how important tertiary similarities are, as opposed

to sequence identity, for the ability of the protein to

form fibrils. In an attempt to answer this question, we

have investigated the fibril-forming properties of

sbTTR and ecTRP in vitro, and compared the results

with those of hTTR.

Our results showed that hTTR, sbTTR and ecTRP

can form fibrillar structures, but under different solu-

tion and temperature conditions. Furthermore,

depending on the conditions used, fibrils of different

morphology were obtained. Recent studies have shown

that sbTTR binds thioflavin-T (ThT) at low pH, sug-

gestive of amyloid [33]. In our study, we verified that

sbTTR forms fibrillar structures at low pH that are

similar in shape to those of hTTR. We also found

that, even though 70% of the amino acids of ecTRP

are different from the respective amino acids in hTTR

and sbTTR, ecTRP has the ability to form Congo Red

(CR)-positive fibrils in vitro if the temperature is

increased sufficiently. Similar findings for ecTRP were

published while this work was in progress [34]. The

Fig. 1. Multiple sequence alignment of representatives of TRPs, TTRs, and TLPs. There are 57 gene clusters in Caenorhabditis elegans,

referred to as TTR-1 to TTR-57 in WORMBASE. Some of these sequences were originally identified as being structurally TTR-like by Sonnham-

mar & Durbin [68]. They seem to be functional and to influence aging in C. elegans, and are referred to as TRPs [69]. TTR-1 to TTR-57 are,

however, not related to the YRGS TRP family [19], which is why we prefer to refer to them as TLPs. The 57 TLP sequences present in

C. elegans are nematode-specific and share low sequence identity with each other; however, sequences TTR-18 to TTR-31 seem to

comprise a subgroup that is also found in other nematodes. (A) In this sequence alignment, TLP representatives from six nematodes have

been aligned with representatives from TTR and TRP. Identical and homologous residues within the three subgroups are marked in red and

pink, respectively. The first residue after signal sequence cleavage is highlighted in black. Sequence numbering refers to mature proteins.

Similarity is defined as amino acid substitutions within one of the following groups: FYW, IVLMF, RK, QDEN, GA, TS, or HNQ. Identical and

similar residues within the TRP family are shown in dark and light green, those within the TTR family in dark and light blue, and those within

the TLP subgroup in dark and light gray. The secondary structure elements are based on hTTR [12]. Residues lining the substrate-binding

channel in TTRs [13] and TRPs [26] are marked with blue stars. The assignment (*.:) shown below the sequences is directly from CLUSTALW2

[75] and refers to alignment of the six TLP sequences only. Only two amino acids (proline and glycine) are conserved throughout the three

groups. Whereas residues at the ligand-binding sites are almost completely conserved in the TTR and TRP families, they are not conserved

within the TLP group. In contrast, the most conserved regions are found at sites corresponding to b-strands B and E in TLPs, and to a-helix E

in TTRs and TRPs. (B) Phylogenetic tree of TRPs, TTRs, and TLPs. The tree was based on the multiple sequence alignment from (A). Caenor-

habditis elegans TRP-R09H10.3 (GI:115532920); C. elegans TRP-ZK697.8 (GI:115534555); Mus Musculus TRP (GI:81916776); Bacillus subtilis

TRP (GI:3915561); Escherichia coli TRP (GI:3915454); Petaurus breviceps TTR (GI:1279636); Sminthopsis macroura TTR (GI:1279727); Gallus

gallus TTR (GI:45384444); Homo sapiens TTR (GI:114318993); Sparus aurata TTR (GI:6648602); Heterodera glycines TLP (GI:8571913); Rado-

pholus similis TLP (GI:145279861); Brugia malayi TLP (GI:170583879); Xiphinema index TLP (GI:55724912); C. elegans TLP (TTR-30,

GI:25153261); Caenorhabditis briggsae TLP (TTR-18 GI:187037056).

Stability and fibril formation of TTR and TRP E. Lundberg et al.

2000 FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 1999–2011 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS

A

BTLP--H. glycines

TLP--B. malayi

TLP--C. elegans--TTR-30

TLP--C. briggsae--TTR-18

TTR--P. breviceps

TTR--S. macroura

TTR--G. gallus

TTR--H. sapiens

TTR--S. aurata

TRP--E. coli

TRP--C. elegans--R09H10.3

TRP--C. elegans--ZK697.8

TRP--M. musculus

TRP--B. subtilis

TLP--X. index

TLP--R. similis

E. Lundberg et al. Stability and fibril formation of TTR and TRP

FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 1999–2011 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS 2001

results emphasize the potential for amyloid formation

as a common property of all proteins, a feature that

can sometimes even bring new functionality [35–37].

The thermal stability of ecTRP was found by differen-

tial scanning calorimetry (DSC) to be approximately

30 C lower than that of sbTTR and hTTR. Compara-

tive studies of structures from homologous thermophiles

and mesophiles have revealed several factors that gener-

ally contribute to the intrinsic thermal stability of pro-

teins [38–40]. These include tighter hydrophobic packing

of the protein core [41–43], increased electrostatic inter-

actions on the surface of the protein [44,45], more pro-

lines and alanines [46,47], and increased hydrogen

bonding of the polypeptide chain [48–50]. In addition,

improved intersubunit contacts within oligomeric pro-

teins contribute to protein stability [51,52]. Here, we

analyze the structural basis for the differences in ther-

mostability of hTTR, sbTTR, and ecTRP.

Results

Partial acid denaturation generates fibrils of hTTR

and sbTTR

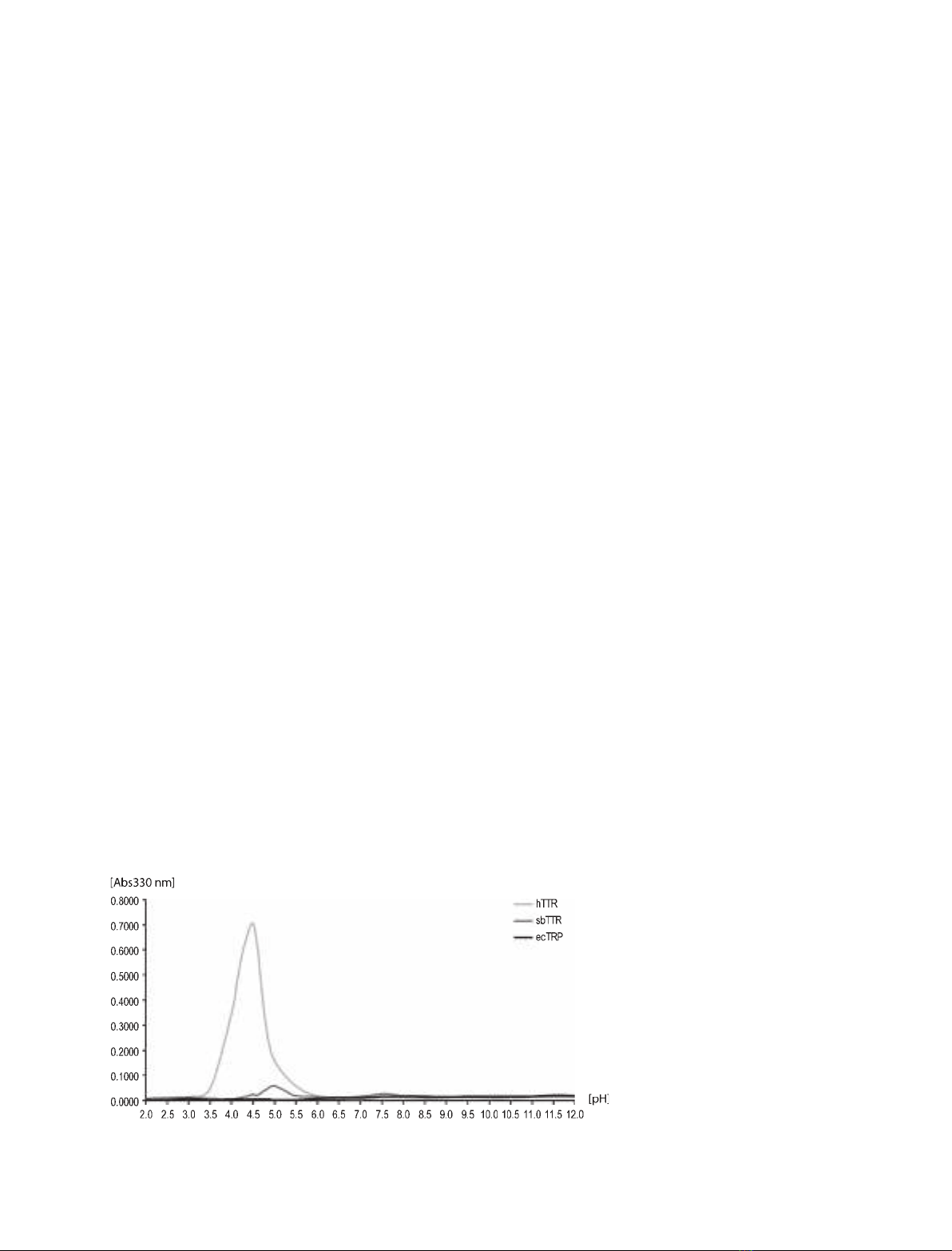

Partial acid denaturation combined with turbidity assays

is a method frequently used to induce and monitor the

degree of protein aggregation and fibril formation of

hTTR [28,53]. Application of this method to the three

proteins in our study showed that hTTR displayed an

increase in turbidity at low pH, with a turbidity maxi-

mum at pH 4.5 (Fig. 2). This is in agreement with previ-

ous results [28,53]. For sbTTR, we measured only minor

turbidity increases at the low pH range of 4.0–5.5, and

for ecTRP, no effect was apparent over the entire pH

range (2–12) (Fig. 2). It should be noted that the pI of

ecTRP is estimated to be 8.2, in contrast to those of

hTTR and sbTTR, which are estimated to be 5.5–6.0.

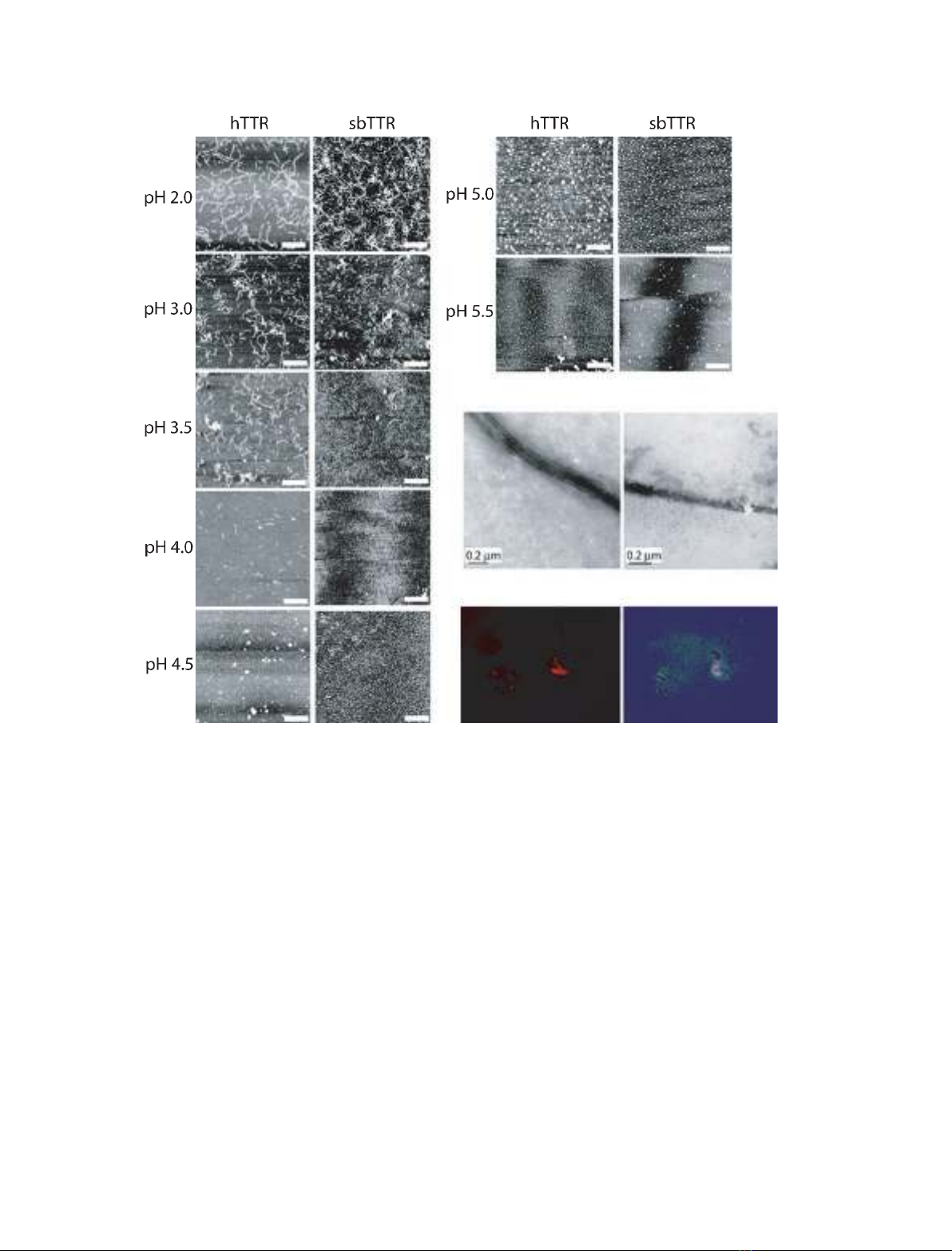

The samples treated at low pH were visualized with

atomic force microscopy (AFM) to determine the

morphologies of the protein aggregates. Both hTTR and

sbTTR displayed fibrils at pH 2.0–3.5 that were very

similar in structure (Fig. 3). For hTTR, small amounts

of fibrillar structures were also formed at pH 4.0. The

thickness of these structures was found to be 1.3 nm,

which means that they were thinner than amyloid fibrils.

Their curved morphology agreed with previous observa-

tions of both hTTR and rTTR in vitro fibrils, suggesting

that they most likely represented protofibrils [32,54–56].

hTTR in vitro fibrils are reported to have widths varying

between 2.8 [55] and 10 nm [54], and the thicker in vitro

fibrils are believed to consist of up to five intertwined

protofilaments [54]. At the pH interval 4.0–5.5, predomi-

nantly amorphous aggregates, rather than fibrillar struc-

tures, were observed in the hTTR samples (Fig. 3A). It

is, however, not possible to quantitatively estimate the

ratio of aggregates to fibrillar structures from the AFM

images. The hTTR and sbTTR samples were also visual-

ized with electron microscopy (EM). The EM images

were consistent with the morphologies that we eluci-

dated from the AFM images, and verified that fibrillar

structures were present in the protein samples at pH 4.5

(Fig. 3B). To determine whether the lack of fibrillar

structures in the hTTR and sbTTR samples at pH 4.5

could be an effect of the technique used for analysis

(that is, the fibrils are unable to bind to mica gels at this

pH), fibril-containing samples of hTTR formed at

pH 2.0 were adjusted to pH 4.5 and incubated for vari-

ous lengths of time. AFM images of this material

showed that the fibrils formed at pH 2.0 persisted at

pH 4.5, thereby verifying that these fibrillar forms can

bind to mica gels even at higher pH (data not shown).

Tinctorial properties of fibrillar structures formed

at low pH

The protein fibrils and aggregates obtained by the

partial acid denaturation experiments were tested for

ThT, which is a fluorescent dye commonly used to

Fig. 2. Turbidity assays for hTTR, sbTTR,

and ecTRP. The turbidity was measured at

330 nm after incubation of protein samples

at 37 C for 72 h.

Stability and fibril formation of TTR and TRP E. Lundberg et al.

2002 FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 1999–2011 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS

assess amyloid fibril formation [57,58], including hTTR

amyloid [59,60]. Pronounced emission at 482 nm, as a

result of ThT binding, was seen for the human and sea

bream samples incubated at pH 2.0 and 2.5, respec-

tively (Fig. 4). This is in agreement with the presence

of the thin fibrils seen with AFM (Fig. 3A). At a pH

value around 3.0, both hTTR and sbTTR showed

significantly reduced ThT binding as compared to that

at lower pH. However, at the slightly higher pH range

of 3.5–4.5, hTTR formed structures that bound to

ThT (Fig. 4). This ThT-binding pattern correlates well

with the increase in turbidity of hTTR observed at

pH 4.5 (Fig. 2). The sbTTR samples did not display

increased ThT binding at pH 3.5–4.5, and demon-

strated only a very small increase in turbidity at this

pH range. ecTRP did not react with ThT at any pH

range tested.

The partially denaturated protein samples were also

tested for CR staining, visualized with EM. Generally,

the ability of fibrils to bind CR and to display a char-

acteristic apple-green birefringence under polarized

light are the two most important criteria for detection

of amyloid fibrils in vivo. Such fibrils are called

CR-positive, but the specificity of this test has recently

been questioned [61,62]. The material from hTTR was

CR-positive at pH 4.0–4.5 (Fig. 3C), in agreement with

previous studies [28,53]. Aggregates from sbTTR, on

the other hand, were not found to be CR-positive at

A

B

C

ab

ab

Fig. 3. (A) AFM images of hTTR (left) and sbTTR (right). The samples were incubated at 37 C for 72 h. Fibrils were present in samples incu-

bated at pH 2.0–3.5, whereas aggregates were predominantly present in samples incubated at pH 4.5–5.5. No fibrils or aggregates were

detected in the ecTRP samples, at any of the pH intervals tested (pH 2.0–12.0; data not shown). The white scale bar is 500 nm. (B) EM

images of fibrils of hTTR (a) and sbTTR (b) incubated at pH 4.5. (C) CR staining of hTTR incubated for 3 days at pH 4.5. (a) shows fluores-

cence (at 594 nm) and (b) shows the characteristic apple-green birefringence with polarized light.

E. Lundberg et al. Stability and fibril formation of TTR and TRP

FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 1999–2011 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS 2003