Chapter 27

Unemployment

David Begg, Stanley Fischer and Rudiger Dornbusch, Economics,

6th Edition, McGraw-Hill, 2000

Power Point presentation by Peter Smith

27.2

Some key terms

■Unemployment rate:

–the percentage of the labour force without a

job but registered as being willing and

available for work

■Labour force

–those people holding a job or registered as

being willing and available for work

■Participation rate

–the percentage of the population of working

age declaring themselves to be in the labour

force

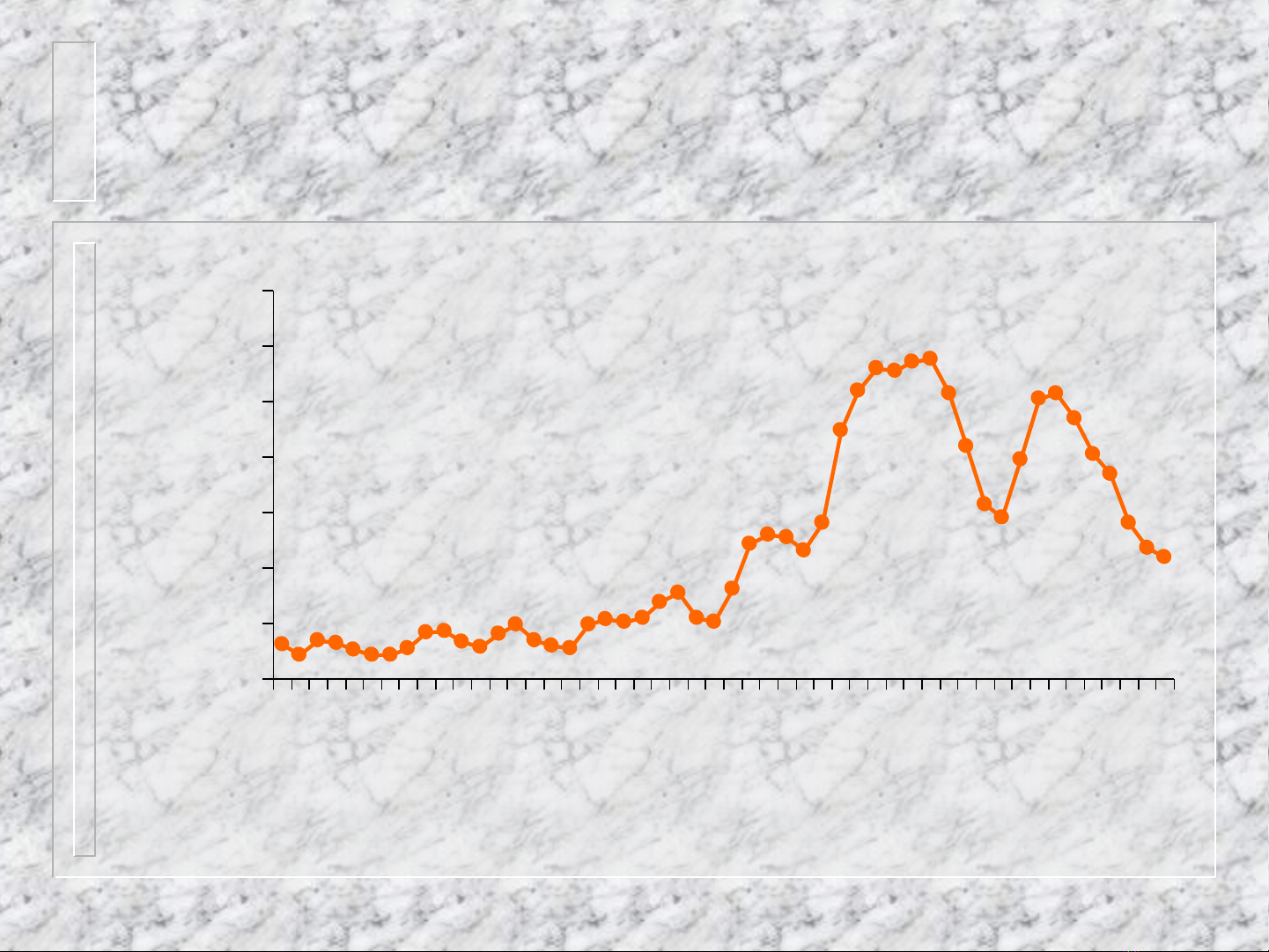

27.3

Unemployment in the UK, 1950-99

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

1950

1970

1990

% p.a.

Source: Economic Trends Annual Supplement, Labour Market Trends

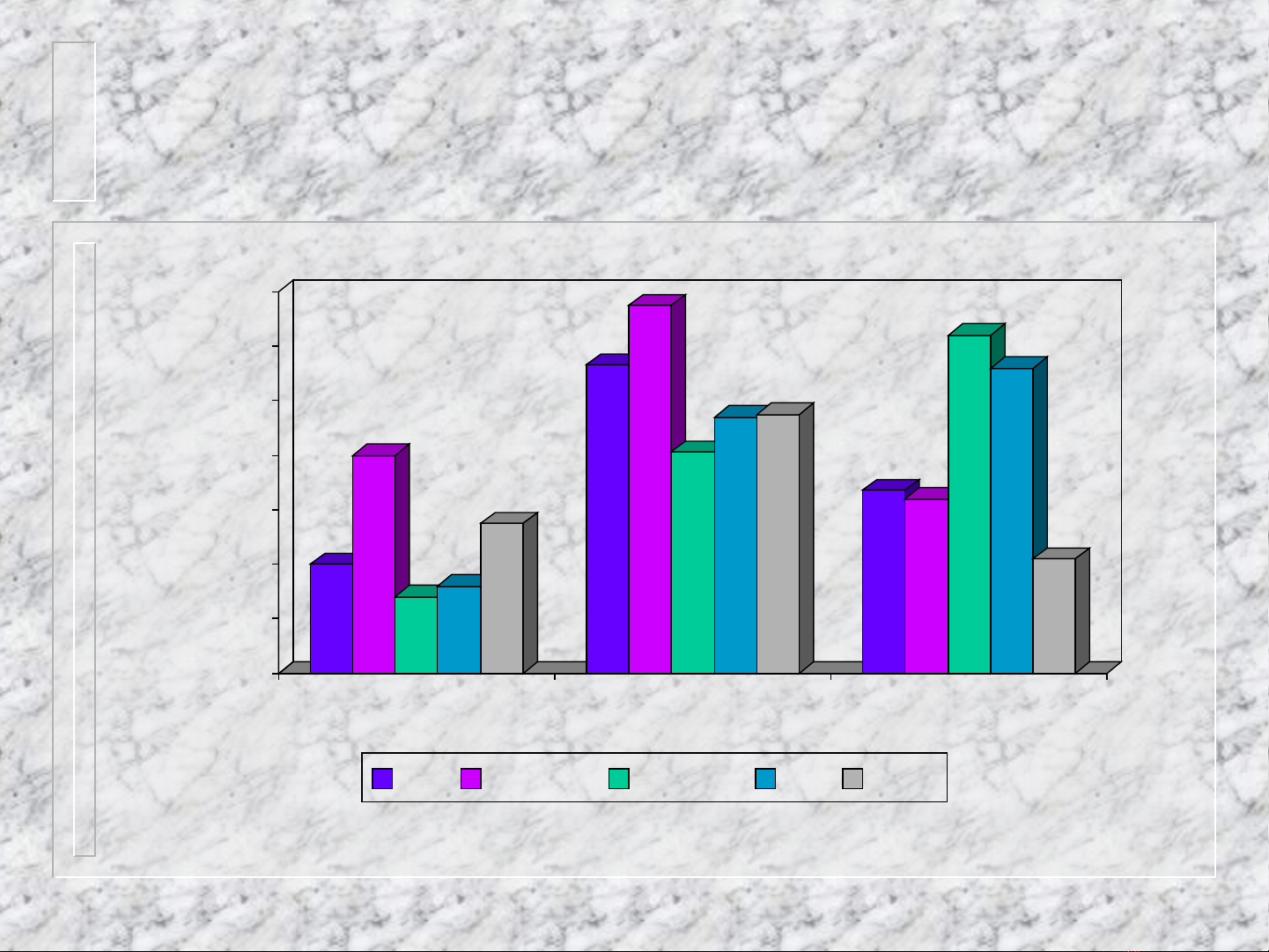

27.4

Unemployment (%) in selected countries

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

%

1972 1982 1999

UK Ireland France EU USA

27.5

Labour market flows

It is tempting to see the labour market in static terms

Working Unemployed

Out of the

labour force but...

![Bài giảng Phương pháp phân tích công việc thuộc chức năng nhiệm vụ [chuẩn SEO]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2020/20200721/chuakieudam/135x160/3491595296860.jpg)

![Hệ thống thang bảng lương theo chức danh công việc [mới nhất 2024]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2019/20190624/leoanh111/135x160/1211561339601.jpg)

![240 câu hỏi trắc nghiệm Kinh tế vĩ mô [chuẩn nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2026/20260126/hoaphuong0906/135x160/51471769415801.jpg)

![Câu hỏi ôn tập Kinh tế môi trường: Tổng hợp [mới nhất/chuẩn nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20251223/hoaphuong0906/135x160/56451769158974.jpg)

![Giáo trình Kinh tế quản lý [Chuẩn Nhất/Tốt Nhất/Chi Tiết]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2026/20260122/lionelmessi01/135x160/91721769078167.jpg)