An active triple-catalytic hybrid enzyme engineered

by linking cyclo-oxygenase isoform-1 to prostacyclin

synthase that can constantly biosynthesize prostacyclin,

the vascular protector

Ke-He Ruan, Shui-Ping So, Vanessa Cervantes, Hanjing Wu*, Cori Wijaya and Rebecca R. Jentzen*

Department of Pharmacological and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Center for Experimental Therapeutics and PharmacoInformatics,

University of Houston, TX, USA

Prostacyclin (prostaglandin I

2

, PGI

2

) [1], which has

strong antiplatelet aggregation and vasodilation prop-

erties [1–4], and is synthesized from endothelial and

vascular smooth muscle cells, has been identified as

one of the most important vascular protectors against

thrombosis and heart disease [5]. Recently, there have

been many new studies that have confirmed the impor-

tance of PGI

2

in vascular protection. For instance, it

Keywords

COX; cyclo-oxygenase; PG12; prostacyclin;

prostaglandin 12

Correspondence

K.-H. Ruan, Department of Pharmacological

and Pharmaceutical Sciences, Center for

Experimental Therapeutics and

PharmacoInformatics, University of

Houston, Room 521, Science & Research 2

Building, Houston, TX 77204-5037, USA

Fax: +1 713 743 1884

Tel: +1 713 743 1771

E-mail: khruan@uh.edu

*Present address

The University of Texas Health Science

Center, Houston, TX, USA

(Received 15 July 2008,

revised 23 September 2008,

accepted 25 September 2008)

doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06703.x

It remains a challenge to achieve the stable and long-term expression (in

human cell lines) of a previously engineered hybrid enzyme [triple-catalytic

(Trip-cat) enzyme-2; Ruan KH, Deng H & So SP (2006) Biochemistry 45,

14003–14011], which links cyclo-oxygenase isoform-2 (COX-2) to prostacy-

clin (PGI

2

) synthase (PGIS) for the direct conversion of arachidonic acid

into PGI

2

through the enzyme’s Trip-cat functions. The stable upregulation

of the biosynthesis of the vascular protector, PGI

2

, in cells is an ideal

model for the prevention and treatment of thromboxane A

2

(TXA

2

)-medi-

ated thrombosis and vasoconstriction, both of which cause stroke, myo-

cardial infarction, and hypertension. Here, we report another case of

engineering of the Trip-cat enzyme, in which human cyclo-oxygenase iso-

form-1, which has a different C-terminal sequence from COX-2, was linked

to PGI

2

synthase and called Trip-cat enzyme-1. Transient expression of

recombinant Trip-cat enzyme-1 in HEK293 cells led to 3–5-fold higher

expression capacity and better PGI

2

-synthesizing activity as compared to

that of the previously engineered Trip-cat enzyme-2. Furthermore, an

HEK293 cell line that can stably express the active new Trip-cat enzyme-1

and constantly synthesize the bioactive PGI

2

was established by a screening

approach. In addition, the stable HEK293 cell line, with constant produc-

tion of PGI

2

, revealed strong antiplatelet aggregation properties through its

unique dual functions (increasing PGI

2

production while decreasing TXA

2

production) in TXA

2

synthase-rich plasma. This study has optimized engi-

neering of the active Trip-cat enzyme, allowing it to become the first to

stably upregulate PGI

2

biosynthesis in a human cell line, which provides a

basis for developing a PGI

2

-producing therapeutic cell line for use against

vascular diseases.

Abbreviations

AA, arachidonic acid; COX, cyclo-oxygenase; COX-1, cyclo-oxygenase isoform-1; COX-2, cyclo-oxygenase isoform-2; ER, endoplasmic

reticulum; FITC, fluorescein isothiocyanate; IP

,

PGI

2

receptor; PGE

2

, prostaglandin E

2

; PGF

2

, prostaglandin F

2

; PGG

2,

prostaglandin G

2;

PGH

2,

prostaglandin H

2;

PGI

2,

prostaglandin I

2

(prostacyclin); PGIS, prostaglandin I

2

(prostacyclin) synthase; SLO, streptolysin-O; TM,

transmembrane domain; TXA

2,

thromboxane A

2;

TXAS, thromboxane A

2

synthase.

5820 FEBS Journal 275 (2008) 5820–5829 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS

was discovered that PGI

2

receptor (IP) -knockout mice

showed an increase in thrombosis tendency [6]. Also,

the suppression of PGI

2

biosynthesis by cyclo-oxygen-

ase isoform-2 (COX-2) inhibitors was linked to

increased rates of heart disease in human clinical trials

[7]. Thus, increasing the biosynthesis of PGI

2

would be

very useful for protection of the vascular system. It is

known that the biosynthesis of prostanoids through

the arachidonate– cyclo-oxygenase (COX) pathway

occurs when arachidonic acid (AA) is first converted

into prostaglandin G

2

(PGG

2

, catalytic step 1), and

then to prostaglandin endoperoxide [prostaglandin H

2

(PGH

2

)] (catalytic step 2) by COX isoform-1 (COX-1)

or COX-2 in cells [8]. The PGH

2

then serves as a com-

mon substrate for downstream synthases, and is isom-

erized to prostaglandin D

2

, prostaglandin E

2

(PGE

2

),

prostaglandin F

2

(PGF

2

), and prostaglandin I

2

(PGI

2

)

or thromboxane A

2

(TXA

2

) by individual synthases

(catalytic step 3). The overproduction of TXA

2

, a pro-

aggregatory and vasoconstricting mediator, has been

identified as one of the key factors causing thrombosis,

stroke, and heart disease [1,2]. PGI

2

is the primary AA

metabolite in vascular walls, and has opposite biolo-

gical properties to that of TXA

2

; it therefore represents

the most potent endogenous vascular protector, acting

as an inhibitor of platelet aggregation and a strong

vasodilator on vascular beds [9–12]. Specifically

increasing PGI

2

biosynthesis requires a highly efficient

chain reaction between COX and PGI

2

synthase

(PGIS), which consists of triple catalytic (Trip-cat)

functions.

Recently, we engineered a hybrid enzymatic protein

with the ability to perform the Trip-cat functions by

linking the inducible COX-2 to PGIS through a trans-

membrane (TM) domain [13,14]. Here, we refer to this

previously engineered enzyme as Trip-cat enzyme-2.

Transient expression of active Trip-cat enzyme-2 in

HEK293 and COS-7 cells has been demonstrated.

However, there are concerns in using Trip-cat enzyme-

2in vivo, because COX-2 has an inducible nature, has

a lower capacity to be stably expressed, and may also

lead to numerous pathological processes, such as

cancers and inflammation. Given the nature of COX-1,

a housekeeping enzyme that is consistently expressed

in cells, we hypothesize that a Trip-cat enzyme,

constructed by linking COX-1 to PGIS, is likely to

demonstrate stable expression in cells and therefore

lead to constant production of the vascular protective

prostanoid PGI

2

. To test this hypothesis, in this article

we report the construction of a new Trip-cat enzyme

linking COX-1 to PGIS, which we call Trip-cat

enzyme-1. Our studies have confirmed that Trip-cat

enzyme-1 can be stably expressed in HEK293 cells and

therefore lead to the generation of a cell line that con-

stantly delivers the vascular protector PGI

2

. This study

has provided a fundamental step towards specifically

and stably upregulating PGI

2

biosynthesis in thera-

peutic cells for the prevention and treatment of throm-

bosis and heart disease.

Results

Design of a new-generation Trip-cat enzyme

(COX-1 linked to PGIS) that directly converts

AA to the vascular protector PGI

2

As described above, we recently invented an approach

for engineering an active hybrid enzyme (Trip-cat

enzyme-2), by linking human COX-2 to PGIS (COX-2–

linker–PGIS), which demonstrated Trip-cat activities in

converting AA to PGG

2

, PGH

2

, and finally PGI

2

[13,14]

(Fig. 1). This finding provided great potential for specif-

ically upregulating PGI

2

biosynthesis in ischemic tissues

through the introduction of the Trip-cat enzyme-1 gene

into these target tissues. On the other hand, there is the

COX-1 enzyme, which is well known to have a similar

function (coupling to PGIS to synthesize PGI

2

in vitro

and in vivo) to that of COX-2. The housekeeping

enzyme COX-1, which has less pathological impact,

could be safer for gene and cell therapies than COX-2,

which is involved in the pathological processes of

PGI2

PGH2

PGG2

3rd

Catalytic

reaction

1st

Catalytic

reaction

2nd

Catalytic

reaction

PGIS

Substrate

AA

TM linker

COX-1

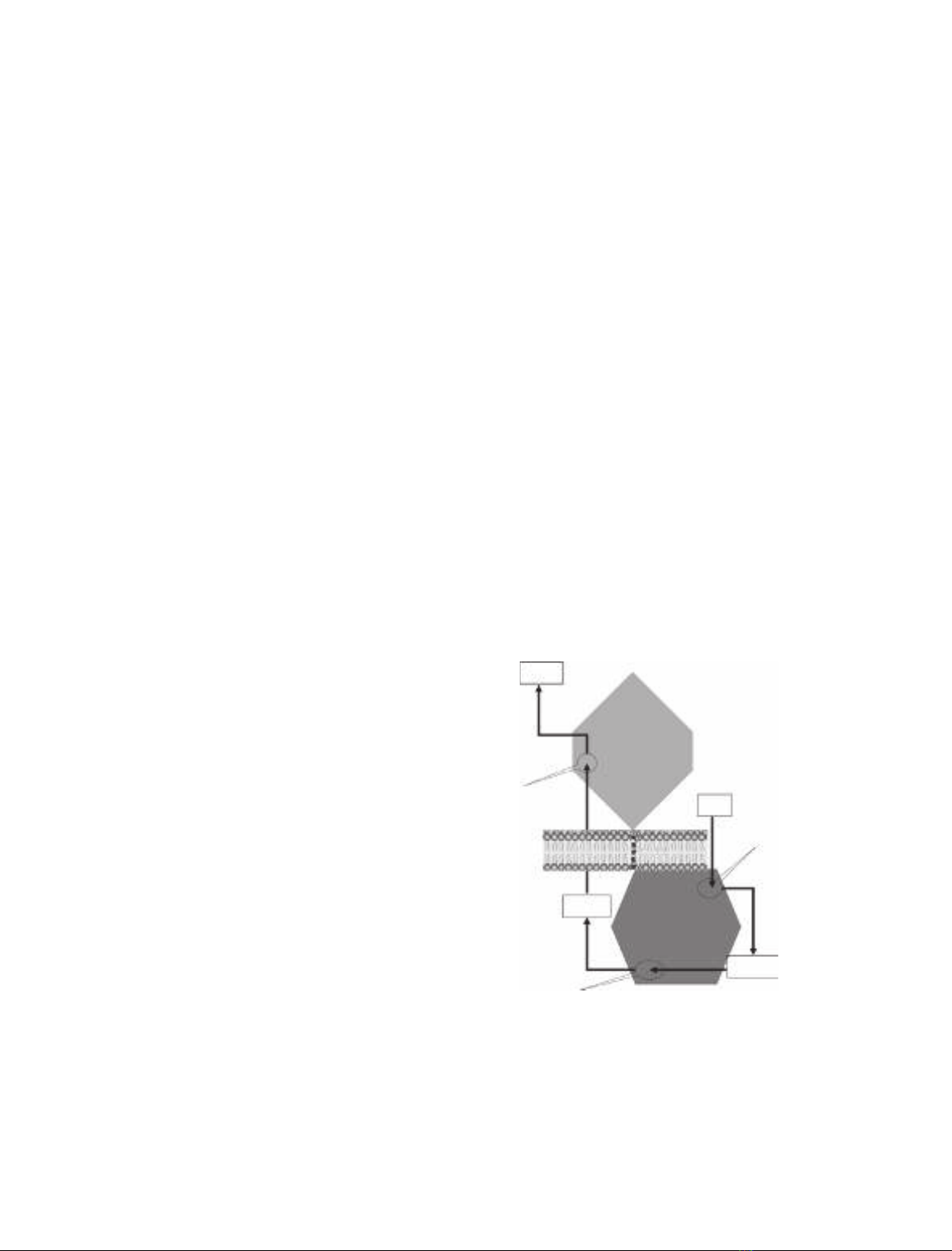

Fig. 1. A model of the newly designed Trip-cat enzyme-1. Trip-cat

enzyme-1 was created by linking COX-1 to PGIS through an opti-

mized TM linker (10 amino acid residues) without alteration of the

protein topologies in the ER membrane. The three catalytic sites in

and reaction products of COX-1 and PGIS are shown.

K.-H. Ruan et al. Prostacyclin-synthesizing protein with COX-1 and PGIS properties

FEBS Journal 275 (2008) 5820–5829 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS 5821

inflammation and cancers, and shows inducible tran-

sient expression. This suggested that the Trip-cat

enzyme containing COX-1 (Fig. 1) may have better

therapeutic potential than that containing COX-2 in

terms of stable expression in cells and pathogenic prop-

erties. Also, the X-ray crystal structure shows that the

membrane orientation and the membrane anchor

domain of COX-1 are similar to those of COX-2. This

led us to design a single molecule containing the cDNA

of human COX-1 and PGIS with a connecting TM lin-

ker derived from human bovine rhodopsin [15] (Fig. 1).

Cloning of Trip-cat enzyme-1 by linking COX-1

to PGIS

A PCR approach was used to link the C-terminus of

human COX-1 (NCBI GenBank ID: NM_080591) to

human PGIS (NCBI GenBank ID: D38145) by a heli-

cal linker with 10 residues (His-Ala-Ile-Met-Gly-

Val-Ala-Phe-Thr-Trp) derived from human rhodopsin.

The resultant cDNA sequence encoding the novel

Trip-cat enzyme-1 (COX-1–10aa–PGIS) was then sub-

cloned into the pcDNA3.1 vector for mammalian cell

expression [13]. Note that the entire cDNA sequence

of Trip-cat enzyme-1 encodes a single human protein

sequence, which could be used for therapeutics.

Expression of the engineered Trip-cat enzyme-1

in HEK293 cells

Despite the many similarities between human COX-1

and COX-2, there are several important differences.

For example, it has been reported that the C-terminal

Leu and the last six residues of COX-1 are important

for the enzyme’s activity [16]. However, they are not

identical to those of COX-2. Therefore, it was interest-

ing to investigate whether the linkage (from the C-ter-

minal Leu of COX-1 to the N-terminus of PGIS) in

Trip-cat enzyme-1 would affect its expression, protein

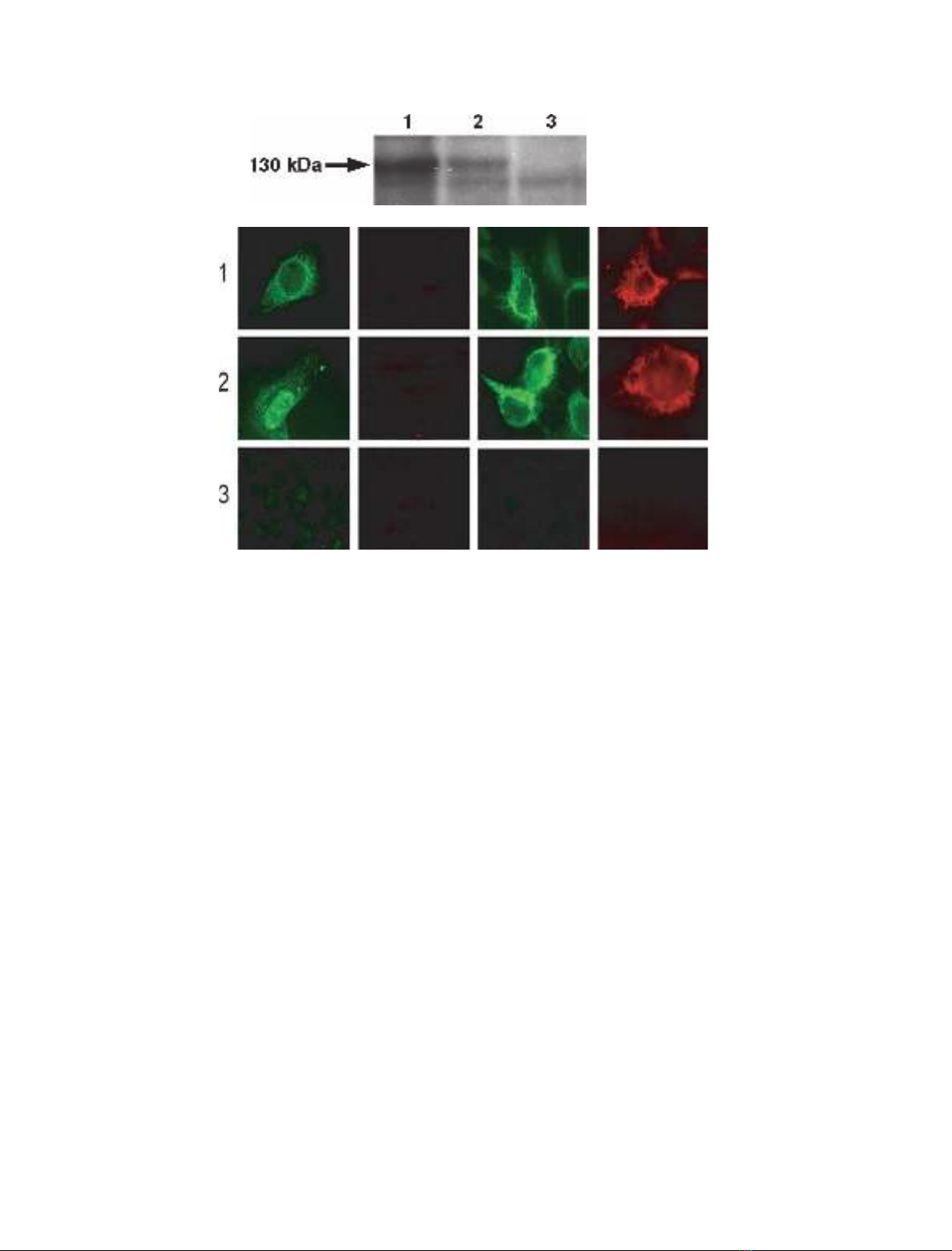

folding, and enzyme activity. Using the constructed

pcDNA3.1 COX-1–10aa–PGIS plasmid, the recombi-

nant COX-1–10aa–PGIS protein was successfully over-

expressed in the HEK293 cell line, showing the correct

molecular mass of approximately 130 kDa in western

blot analysis (Fig. 2A, lane 1). This indicated that the

linkage from the C-terminal Leu of COX-1 to the

N-terminus of PGIS had no effect on Trip-cat enzyme

expression. In addition, a comparison of the expression

levels between COX-1–10aa–PGIS and COX-2–10aa–

PGIS revealed that the transfected HEK293 cells

expressed approximately three-fold more COX-1–

10aa–PGIS protein than COX-2–10aa–PGIS protein

under identical conditions (Fig. 2A, lane 2).

Subcellular localization of COX-1–10aa–PGIS

To determine whether the linkage of the C-terminal

Leu of COX-1 to PGIS had any effects on the sub-

cellular localization of Trip-cat enzyme-1, HEK293

cells expressing the enzyme COX-1–10aa–PGIS were

permeabilized and stained. Nonsignificant differences

were observed in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER)

staining patterns for the cells treated with streptolysin-

O (SLO), which selectively permeabilized the cell

membrane, and with saponin, which generally permea-

bilized both the cell and the ER membranes (Fig. 2B).

The results indicated that the modification of the link-

age between the COX-1 Leu residue and the PGIS

N-terminus had no significant effect on the subcellular

localization of COX-1–10aa–PGIS in the cells. The

idea that the PGIS domain is located on the cytoplas-

mic side of the ER and that the COX-1 domain is

located on the ER lumen for the overexpressed COX-

1–10aa–PGIS was also supported by immunostaining.

Antibody against PGIS was used to stain the cells trea-

ted with SLO or saponin, but antibody against COX-1

would only stain the cells treated with saponin

(Fig. 2B). These data further confirmed that the 10

amino acid linkage between COX-1 to PGIS had no

significant effects on the subcellular localization of

COX-1 and PGIS in the ER membrane.

Trip-cat activities of Trip-cat enzyme-1 in directly

converting AA to the vascular protector PGI

2

The biological activities of HEK293 cells expressing

the different eicosanoid-synthesizing enzymes that con-

vert AA to PGI

2

were assayed by the addition of

[

14

C]AA. The resultant [

14

C]eicosanoids, metabolized

by the enzymes in the cells, were profiled by HPLC

analysis (HPLC separation linked to an automatic

scintillation analyzer; Fig. 3). The Trip-cat activities

that occur during the conversion of [

14

C]AA to [

14

C]6-

keto-PGF

1a

(degraded PGI

2

) require two individual

enzymes, COX-1 and PGIS, in HEK293 cells

(Fig. 3A), because neither COX-1 (Fig. 3B) nor PGIS

(Fig. 3C) alone could produce [

14

C]6-keto-PGF

1a

from

[

14

C]AA in HEK293 cells. However, the cells express-

ing Trip-cat enzyme-1 were able to integrate the Trip-

cat activities of COX-1 and PGIS by converting the

added [

14

C]AA to the end-product, [

14

C]6-keto-PGF

1a

(Fig. 3D). It should be noted that in HEK293 cells

expressing Trip-cat enzyme-1, most of the added

[

14

C]AA was converted to [

14

C]6-keto-PGF

1a

, with

very low amounts of byproducts. In contrast, the cells

coexpressing COX-1 and PGIS synthesized less PGI

2

and produced significant amounts of other unidentified

Prostacyclin-synthesizing protein with COX-1 and PGIS properties K.-H. Ruan et al.

5822 FEBS Journal 275 (2008) 5820–5829 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS

lipid molecules. These data clearly indicated that the

enzymatic conversion of AA to PGI

2

is more efficient

with Trip-cat enzyme-1 than with coexpressed individ-

ual COX-1 and PGIS.

Enzyme kinetics of Trip-cat enzyme-1 compared

to those of its parent enzymes

In cells coexpressing COX-1 and PGIS, the coordina-

tion of COX-1 and PGIS in the ER membrane (for

the biosynthesis of PGI

2

from AA) is very fast. Only

120 s were required for 50% of the maximum activity

to be reached (Fig. 4A, triangles). The reaction was

almost saturated after approximately 5 min. The

amount of PGI

2

produced when the reaction was

extended from 5 min to 15 min increased by only 5%.

On the other hand, cells expressing the engineered

Trip-cat enzyme-1 (Fig. 4A, closed circles) showed the

same time-course pattern as that of the coexpressed

wild-type COX-1 and PGIS. In addition, Trip-cat

enzyme-1 also showed an identical dose-dependent

response to that of the parent enzymes in the biosyn-

thesis of PGI

2

(Fig. 4B). The K

m

and V

max

values for

Trip-cat enzyme-1 were approximately 5 and 400 lm,

respectively; these are almost identical to those of the

coexpressed COX-1 and PGIS. This study has indi-

cated that the expressed Trip-cat enzyme-1 in the cells

has correct protein folding, subcellular localization and

native enzymatic functions in a single folded protein,

similar to to its parent enzymes.

Establishing stable expression of Trip-cat

enzyme-1 in cells

Stable expression of the engineered Trip-cat enzyme-1

in cells is the basis for having the cells constantly pro-

duce PGI

2

. In this study, an HEK293 cell line was

used as the model for testing. After G418 screening for

b

acd

B

A

Fig. 2. (A) Western blot analysis for overexpressed COX-1–10aa–PGIS and COX-2–10aa–PGIS in HEK293 cells. HEK293 cells transiently trans-

fected with cDNA of COX-1–10aa–PGIS (lane 1) or COX-2–10aa–PGIS (lane 2), or the pcDNA3.1 vector alone (lane 3), were solubilized and

separated by 7% SDS ⁄PAGE, and then transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The expressed Trip-cat enzymes were stained with antibody

against PGIS. The molecular mass (130 kDa) of the engineered enzymes is indicated by an arrow. (B) Immunofluorescence micrographs of

HEK293 cells. In brief, the cells were grown on coverslides and transfected with the cDNA plasmid(s) of COX-1–10aa–PGIS (row 1), cotrans-

fected COX-1 and PGIS (row 2), or transfected with the pcDNA3.1 vector alone (row 3). The cells were permeabilized by SLO (columns a and

b) or saponin (columns c and d), and then incubated with affinity-purified rabbit antibody against PGIS peptide (columns a and c) or mouse

antibody against COX-1 (columns b and d) [13]. The bound antibodies were stained with FITC-labeled goat anti-(rabbit IgG) (columns a and c)

or rhodamine-labeled goat anti-(mouse IgG) (columns b and d). The stained cells were then examined by fluorescence microscopy [13].

K.-H. Ruan et al. Prostacyclin-synthesizing protein with COX-1 and PGIS properties

FEBS Journal 275 (2008) 5820–5829 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS 5823

the transiently transfected HEK293 cells containing the

Trip-cat enzyme-1 cDNA, cells stably expressing Trip-

cat enzyme-1 were successfully created, as indicated by

the enzyme activity assays showing continuous

[

14

C]PGI

2

production after the addition of [

14

C]AA

(Fig. 5, black squares). However, the same cells trans-

fected with COX-2–10aa–PGIS cDNA could only pro-

duce PGI

2

for a few days (Fig. 5, open squares), due

to a failure in the stable expression of Trip-cat

enzyme-2. This study indicated that the engineered

Trip-cat enzyme-1 most likely adopted the housekeep-

ing properties of COX-1, which produced constant

expression in the cells, whereas Trip-cat enzyme-2

mainly adopted the properties of inducible COX-2,

which expressed the protein for only a short period of

time.

Antiplatelet aggregation

The effects of HEK293 cells expressing COX-1–10aa–

PGIS on antiplatelet aggregation were explored. It is

known that platelets contain large amounts of COX-1

and thromboxane A

2

synthase (TXAS). When AA was

added to the platelet-rich plasma, the platelets began

to aggregate in minutes (Fig. 6A, line a). However, this

aggregation was completely blocked in the presence of

cells expressing COX-1–10aa–PGIS (Fig. 6A, line b).

In contrast, the aggregation was only partially blocked

in the presence of cells coexpressing COX-1 and PGIS

(Fig. 6A, line c). This indicated that AA was not only

converted into PGI

2

(by COX-1 and PGIS), to act

against platelet aggregation, but also converted into

TXA

2

, promoting platelet aggregation by the abundant

TXAS in the platelets. In contrast, no effects were

observed with the nontransfected, control HEK293

cells (Fig. 6A, line d). From these observations, it is

clear that the engineered Trip-cat enzyme-1 has supe-

rior antiplatelet aggregation activity to coexpressed

COX-1 and PGIS.

To test whether Trip-cat enzyme-1 can indirectly

inhibit platelet aggregation induced by other factors,

such as collagen (through non-COX pathways), it is

necessary to compare the effects of HEK293 cells

(expressing Trip-cat enzyme-1) on human platelets

induced by collagen (Fig. 6B, bars 1 and 2) with those

of the AA-induced platelets (Fig. 6B, bars 3 and 4). It

is clear that cells expressing Trip-cat enzyme-1 could

not only directly inhibit AA-induced platelet aggre-

gation (Fig. 6B, bar 4), but also significantly inhibit

collagen-induced platelet aggregation by up to 50%

(Fig. 6B, bar 2).

Competitively upregulating PGI

2

biosynthesis in

the presence of platelets

To further demonstrate the competitive upregulation

of PGI

2

biosynthesis by COX-1–10aa–PGIS in the

presence of TXAS, [

14

C]AA was added to platelet-rich

plasma containing endogenous COX-1 and TXAS, in

the presence and absence of cells stably expressing

CPM

0

100

200

300

400

A

[14C]-6-keto-PGF1α

[

14

C]-AA

010203040

0

100

200

300

400

D

[14C]-6-keto-PGF1α

[14C]-AA

0 10 20 30 40

0

100

200

300

400

C

[14C]-AA

0

100

200

300

400

B

Non specific peak

[

14

C]-AA

Fig. 3. Determination of the Trip-cat activi-

ties of the fusion enzymes for directly con-

verting AA to PGI

2

, using an isotope-HPLC

method for HEK293 cells. Briefly, the cells

(0.1 ·10

6

) transfected with the cDNA(s)

of both COX-1 and PGIS (A), COX-1 (B),

PGIS (C) and COX-1–10aa–PGIS (D) were

washed and then incubated with [

14

C]AA

(10 lM) for 5 min. The metabolized

[

14

C] eicosanoids produced from the [

14

C]AA

in the supernatant were analyzed by HPLC

on a C18 column (4.5 ·250 mm) connected

to a liquid scintillation analyzer. The total

counts for the specific peaks in each assay

are approximately: 400 counts in (A); 550

counts in (B); 600 counts in (C); and 750

counts in (D).

Prostacyclin-synthesizing protein with COX-1 and PGIS properties K.-H. Ruan et al.

5824 FEBS Journal 275 (2008) 5820–5829 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS