BchJ and BchM interact in a 1 : 1 ratio with the

magnesium chelatase BchH subunit of

Rhodobacter capsulatus

Artur Sawicki and Robert D. Willows

Department of Chemistry and Biomolecular Sciences, Macquarie University, Sydney, NSW, Australia

Keywords

bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis; BchJ;

BchM; magnesium chelatase;

O-methyltransferase

Correspondence

R. D. Willows, Department of Chemistry

and Biomolecular Sciences Macquarie

University, NSW 2109, Australia

Fax: +6 298508245

Tel: +6 298508146

E-mail: robert.willows@mq.edu.au

Website: http://www.cbms.mq.edu.au

(Received 23 December 2009, revised 11

August 2010, accepted 9 September 2010)

doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07877.x

Substrate channeling between the enzymatic steps in the (bacterio)chloro-

phyll biosynthetic pathway catalyzed by magnesium chelatase (BchI ⁄ChlI,

BchD ⁄ChlD and BchH ⁄ChlH subunits) and S-adenosyl-l-methionine:mag-

nesium-protoporphyrin IX O-methyltransferase (BchM ⁄ChlM) has been

suggested. This involves delivery of magnesium-protoporphyrin IX from

the BchH ⁄ChlH subunit of magnesium chelatase to BchM ⁄ChlM. Stimula-

tion of BchM ⁄ChlM activity by BchH ⁄ChlH has previously been shown,

and physical interaction of the two proteins has been demonstrated. In

plants and cyanobacteria, there is an added layer of complexity, as Gun4

serves as a porphyrin (protoporphyrin IX and magnesium-protoporphy-

rin IX) carrier, but this protein does not exist in anoxygenic photosynthetic

bacteria. BchJ may play a similar role to Gun4 in Rhodobacter, as it has

no currently assigned function in the established pathway. Purified recom-

binant Rhodobacter capsulatus BchJ and BchM were found to cause a shift

in the equilibrium amount of Mg-protoporphyrin IX formed in a magne-

sium chelatase assay. Analysis of this shift revealed that it was always in a

1 : 1 ratio with either of these proteins and the BchH subunit of the mag-

nesium chelatase. The establishment of the new equilibrium was faster with

BchM than with BchJ in a coupled magnesium chelatase assay. BchJ

bound magnesium-protoporphyrin IX or formed a ternary complex with

BchH and magnesium-protoporphyrin IX. These results suggest that BchJ

may play a role as a general magnesium porphyrin carrier, similar to one

of the roles of GUN4 in oxygenic organisms.

Structured digital abstract

lMINT-7994803:bchI (uniprotkb:P26239), bchD (uniprotkb:P26175)andbchH (uniprotkb: P26162)

physically interact (MI:0915)bycosedimentation in solution (MI:0028)

lMINT-7994743:bchJ (uniprotkb:P26169), bchI (uniprotkb:P26239), bchD (uniprotkb:P26175)

and bchH (uniprotkb:P26162)physically interact (MI:0915)by cosedimentation in solution (MI:0028)

lMINT-7994762:bchM (uniprotkb:P26236), bchH (uniprotkb:P26162), bchD (uniprotkb: P26175)

and bchI (uniprotkb:P26239)physically interact (MI:0915)bycosedimentation in solution

(MI:0028)

Abbreviations

BchM, S-adenosyl-L-methionine:magnesium-protoporphyrin IX O-methyltransferase; Mg-proto, magnesium-protoporphyrin IX;

proto, protoporphyrin IX; SAM, S-adenosyl-L-methionine.

FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 4709–4721 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS 4709

Introduction

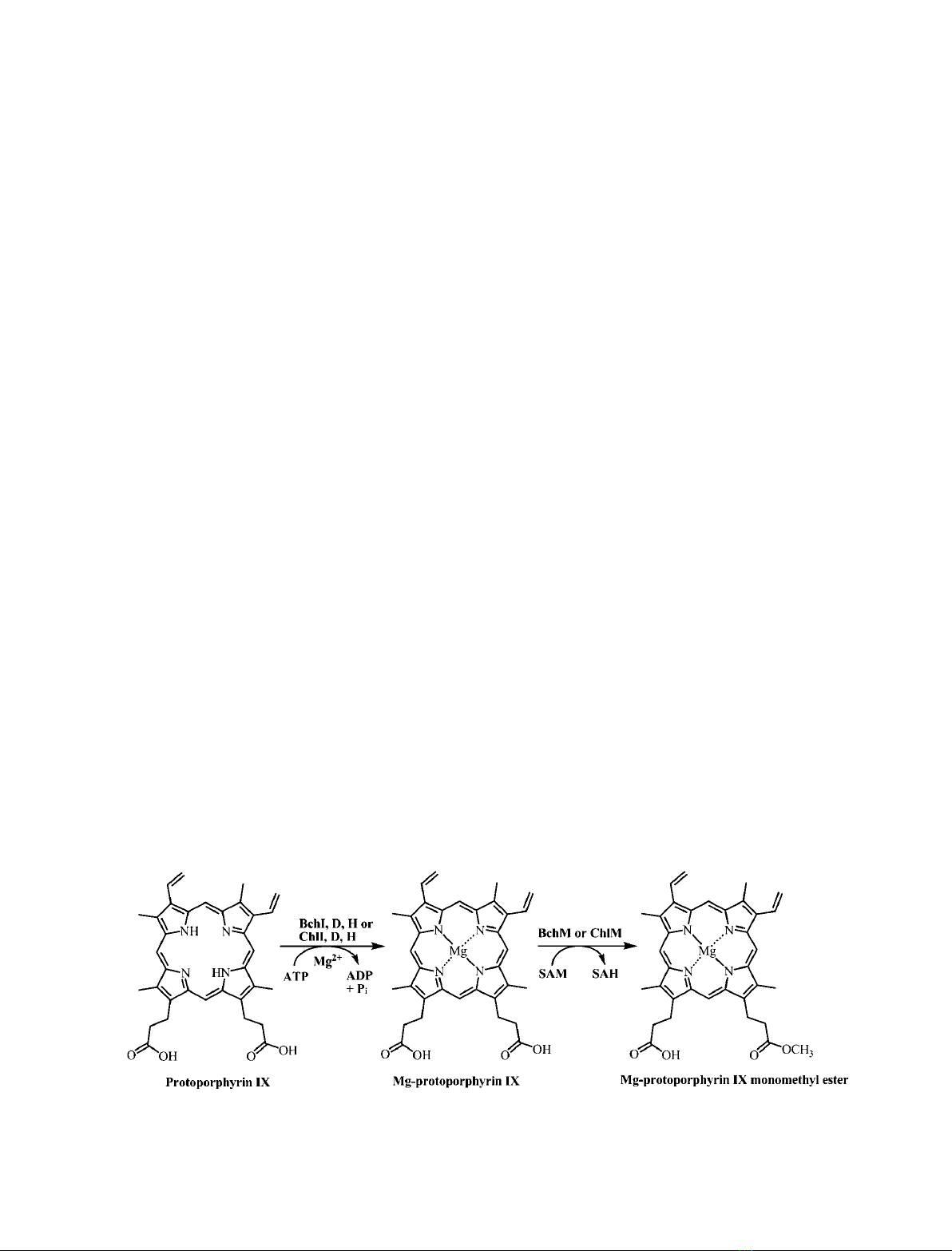

Magnesium chelatase (EC 6.6.1.1) and S-adenosyl-l-

methionine:magnesium-protoporphyrin IX O-methyl-

transferase (BchM) (EC 2.1.1.11) catalyze sequential

steps of the (bacterio)chlorophyll biosynthetic pathway

[1,2]. Magnesium chelatase requires free magnesium

and ATP hydrolysis to convert protoporphyrin IX

(proto) to magnesium-protoporphyrin IX (Mg-proto)

[3–5]. This is followed by O-methyltransferase using

the ubiquitous methylating molecule S-adenosyl-l-

methionine (SAM) to convert Mg-proto to Mg-proto

monomethyl ester [6] (Fig. 1). Magnesium chelatase is

the more complex of the two enzymes, being composed

of at least three subunits. It consists of BchI, BchD

and BchH subunits in bacteriochlorophyll biosynthetic

bacteria, or ChlI, ChlD and ChlH subunits in chloro-

phyll biosynthetic organisms, including bacteria, algae

and plants. There are differences in the complexity of

magnesium chelatase, depending on the organism. For

example, Arabidopsis thaliana has two ChlI isoforms

[7], with each protein contributing to magnesium

chelatase activity and complex formation [8–10]. The

green sulfur bacterium Chlorobaculum tepidum has the

unique property of having three isoforms of BchH,

with suggestions of regulatory properties of at least

one subunit [11]. BchI and BchD hexamers [12,13]

form a symmetrically stacked BchID complex, with

each subunit composed of a trimer of dimers [12], and

BchD providing a stable platform for BchI [14]. The

largest subunit of magnesium chelatase, BchH, con-

tains bound proto [15–17] and transiently interacts

with the BchID complex [18]. This interplay initiates a

burst of ATPase activity supplied by BchI, which

drives magnesium chelation to form Mg-proto [18,19].

It has been shown in plants (A. thaliana) and cyano-

bacteria (Synechocystis) that a subsidiary porphyrin-

binding protein, Gun4, associates with ChlH and

increases magnesium chelatase activity [20–22]. This

interaction was recently localized at the chloroplast

membranes [23], which is consistent with the findings

of single-protein studies showing both Gun4 and ChlH

existing in the stroma and membrane [20,24,25].

Currently, there is no identified homolog of Gun4 in

anoxygenic photosynthetic bacteria, and it was sug-

gested that BchJ, a protein that is absent in plants,

algae and most bacteria, could play a similar role to

Gun4 in purple (sulfur and nonsulfur) bacteria and

green sulfur bacteria [1]. This was postulated because

BchJ lacks 8-vinyl reductase activity [1], contradicting

the conclusions drawn from previous mutational

studies of bchJ [26]. However, the role of BchJ

has not been studied, so it has no classified role in

bacteriochlorophyll biosynthesis.

O-methyltransferase was thoroughly characterized

biochemically in the 1970s to 1980s [27–29], with stud-

ies also being conducted on highly purified His-tagged

enzymes from Synechocystis [30,31], Rhodobacter

capsulatus [32] and C. tepidum [11]. The enzyme is

membrane-associated [33] and is a high molecular mass

polymer in anaerobic bacteria [11,32], whereas the

cyanobacterial form is soluble as a monomer [30]. The

recent report showing the potential of a continuous

coupled colorimetric assay for SAM-dependent methyl-

transferase enzymes [34] was validated with ChlM of

Synechocystis, yielding kinetic constants comparable to

those found in previous uncoupled HPLC-based

stopped assays for O-methyltransferase [35]. Other

work has shown an inextricable link between folate

biosynthesis and O-methyltransferase activity, which is

attributable to the C1 pathway and SAM ⁄S-adenosyl-

l-homocysteine (SAH) metabolic levels [36].

The interaction between magnesium chelatase and

O-methyltransferase has been known for over 35 years,

through initial experiments using whole cells of Rho-

dobacter sphaeroides [37]. However, the precise nature

Fig. 1. Magnesium chelatase and O-methyl transferase reactions.

Interaction of BchM ⁄BchJ with magnesium chelatase A. Sawicki and R. D. Willows

4710 FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 4709–4721 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS

of the interaction was not apparent until much later,

particularly because of the complexity of magnesium

chelatase. A breakthrough occurred with the discovery

that BchH is the porphyrin-binding subunit, with a

1 : 1 molar ratio of protein ⁄porphyrin [17]. As this

subunit shares the ability to bind Mg-proto with

O-methyltransferase, interactions between BchH ⁄ChlH

of magnesium chelatase and O-methyltransferase may

be possible. Studies with Synechocystis showed sub-

stantial stimulation of O-methyltransferase activity

with ChlH, up to 10-fold on a millisecond timescale

[38]. A 1.3–1.6-fold increase in O-methyltransferase

activity was also found with BchS and BchT isoforms

of BchH from C.tepidum [11]. BchH from this species

actually reduced O-methyltransferase activity, prompt-

ing the idea that it could be involved in regulation

[11]. Some evidence also exists for BchH–BchM inter-

actions in R. capsulatus [39]; however, crude protein

preparations were used in this study, and the precise

molecular interaction could not be deduced. Our

previous findings showed no distinct impact of

O-methyltransferase activity upon addition of various

magnesium chelatase subunits, including the fully func-

tional BchIDH complex [32]. In tobacco plants that

were transgenic for sense or antisense ChlM, magne-

sium chelatase and O-methyltransferase activities and

protein expression were found to be in a constant

ratio, and an interaction was demonstrated between

ChlM and ChlH [40,41].

In this article, we present further evidence highlight-

ing the interaction between magnesium chelatase,

BchM and BchJ from the purple nonsulfur bacterium

R. capsulatus. Our results predominantly focus on the

shift in magnesium chelatase reaction equilibria of

proto ⁄Mg-proto upon addition of BchM or BchJ. We

provide kinetic evidence of a direct interaction between

BchM or BchJ and the BchH Mg-proto subunit of

magnesium chelatase, and show a concentration-depen-

dent effect. Our data also suggest that BchJ may serve

as an Mg-proto carrier between the BchH Mg-proto

subunit and BchM.

Results and Discussion

Physical and structural properties of BchJ

His-tagged BchJ was readily purified to homogeneity

in a single step by metal affinity chromatography

(Fig. S1). BchJ (22 kDa) behaved as a high molecular

mass complex (> 200 kDa) in size-exclusion chroma-

tography, even in the presence of the detergent Tri-

ton X-100 and dithiothreitol (Fig. S2). It has already

been shown, by gel filtration, that BchM exists as a

high molecular mass multimer in both purple nonsul-

fur and green sulfur bacteria [11,32], and this is differ-

ent to the situation with ChlM from Synechocystis,

which exists as a monomer [30].

Despite the large aggregates, BchM is enzymatically

active (Fig. S3), and CD spectroscopy of BchM and

BchJ indicates that they have similar and well-defined

secondary structure compositions, with the majority of

the structure being a-helical (52–53%). There is a rela-

tively large proportion of unordered structure

(19% ⁄25%) for BchJ ⁄BchM, and BchJ has a higher

proportion of b-strands than BchM (20.8% ⁄9.1%)

(Fig. 2 and Table S1).

Effect of magnesium on BchM and BchJ, and

their interactions with magnesium chelatase

As coupled magnesium chelatase assays with BchM or

BchJ require free magnesium, we first determined

A

B

Fig. 2. CD spectra of BchM or BchJ with Mg-proto. Experiments

were performed in 10 mMsodium phosphate (pH 7.6), 40 lMTri-

cine ⁄NaOH (pH 8.0) and 8.6 mMglycerol. The concentrations

of BchM, BchJ and Mg-proto (where used) were all 400 nM. The

x-axis is divided into two sections for clarity, with the left-hand side

providing secondary structural information on the protein, and the

right-hand side depicting any interaction of protein with Mg-proto in

the Soret region. (A) BchM alone (open circles) or BchM together

with Mg-proto (closed circles). (B) BchJ alone (open circles) or BchJ

together with Mg-proto (closed circles).

A. Sawicki and R. D. Willows Interaction of BchM ⁄BchJ with magnesium chelatase

FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 4709–4721 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS 4711

whether magnesium would be detrimental to BchM or

BchJ individually in terms of solubility. Free magne-

sium above 2mmcaused substantial precipitation of

BchM, whereas BchJ was mildly affected at 8mm

(Fig. 3A). In terms of their effect on magnesium

chelatase, BchM, BchJ and the detergent Tween-80 all

increased the product formation of magnesium

chelatase in a similar manner at concentrations of free

magnesium above 2 mm. BchM also showed this effect

at the lower free magnesium concentrations tested

(0.78 and 1.2 mm) (Fig. 3B). The aggregation of BchM

in this study could explain the previously observed

adverse effect of magnesium on O-methyltransferase

activity (65% reduction at 10 mm) [32]. The apparent

stimulatory effect of BchM, BchJ or Tween-80 on

magnesium chelation (Fig. 3B) in a 90 min stopped

assay may be attributable to stabilization of the

Mg-proto product and ⁄or interaction with one or

more of the magnesium chelatase subunits.

Using the aggregation of BchM or BchJ to

coprecipitate magnesium chelatase subunits

We further analyzed interactions of magnesium chela-

tase with BchM or BchJ by looking at the distribution

of proteins into soluble and insoluble fractions. It

should be noted that the supernatant fractions

(Fig. 4A) had one-sixth of the relative loading of the

pellet fractions (Fig. 4B). At the magnesium concentra-

tion used, BchH was soluble, BchM was largely insolu-

ble, and BchJ existed in both the soluble and insoluble

fractions (Fig. 4A,B). Addition of BchM or BchJ to

magnesium chelatase significantly increased the pro-

portion of BchH in the insoluble fraction. There was a

less distinct increase in BchI and BchD in the insoluble

fraction, suggesting that there is a physical interaction

between BchH and BchM or BchH and BchJ.

Spectroscopic analysis of BchM or BchJ with

Mg-proto and proto; Soret and far-UV changes

BchH can bind proto and Mg-proto [15–17], so we

tested the ability of BchM or BchJ to bind proto and

Mg-proto, because this may provide more information

on BchM ⁄BchJ–BchH interactions. Both BchM and

BchJ could bind proto and Mg-proto in vitro,as

determined with absorbance spectroscopy (Fig. 5). The

porphyrin Soret peaks of Mg-proto and proto were

red-shifted, by 10 and 25 nm, respectively, when

they were added to BchM or BchJ. A similar shift was

observed with Tween-80 but not with an alterative

protein such as aldolase. The similar spectral changes

induced by Tween-80, BchM and BchJ indicate a

change in the environment of proto ⁄Mg-proto similar

to micellar Tween-80, implying that the porphyrins

bind in a hydrophobic environment on these proteins.

The shift in the Soret peak is often characteristic of a

nonplanar distortion of the porphyrins [42]. Distortion

A

B

Fig. 3. Precipitation of BchM or BchJ with magnesium, and the

effect of these conditions on magnesium chelatase equilibria. All

experiments contained final concentrations as described for magne-

sium chelatase assays, except for 3.2 mMdithiothreitol, 0.5 mM

ATP, and variable free magnesium: 0.38, 0.78, 1.2, 2.0, 2.9, 3.7,

7.9 and 12 mM. Where stated, 87 nMBchH–proto, 850 nM

BchM ⁄BchJ, and 64 lMTween-80 were also included. (A) Bradford

assays of BchM or BchJ with increasing magnesium concentra-

tions. Assays were performed by adding the following components:

3.6 lL of BchID buffer (assay buffer with 4.4 mMdithiothreitol,

10 mMurea, 3.5 mMglycerol), 23.8 lL of MgATP (assay buffer

with 4.4 mMdithiothreitol, and variable MgCl

2

concentrations: 0,

0.96, 1.93, 3.8, 5.8, 7.7, 17 and 27 mM) and 27.5 lL of either

BchM (open circles) or BchJ (closed circles). Samples were centri-

fuged (18 000 gfor 7 min at room temperature), and the superna-

tant was added to Bradford reagent (Bio-Rad) and compared with a

standard curve (BSA) to generate the final concentrations on the

y-axis. (B) Magnesium chelatase assays, with the y-axis represent-

ing the total Mg-proto produced at equilibrium. BchID (13.3 lL)

was refolded in assay buffer as stated above, and diluted to 100 lL

with variable concentrations of MgATP; this was followed by addi-

tion of 100 lL of BchH–proto together with either buffer alone

(50 mMTricine ⁄NaOH, pH 8.0, 19 mMglycerol, 2 mMdithiothreitol)

(open squares), BchM in buffer (open circles), BchJ in buffer

(closed circles) or Tween-80 in buffer (closed diamonds).

Interaction of BchM ⁄BchJ with magnesium chelatase A. Sawicki and R. D. Willows

4712 FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 4709–4721 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS

of the tetrapyrrole nucleus is common in nature

[42], being most notably seen with many heme (iron

tetrapyrrole)-binding proteins, but also with nickel

porphyrin-binding protein (cofactor F

430

) and bacterio-

chlorophyll-binding photosynthetic reaction centers.

We further tested the visible and far-UV properties

of BchM and BchJ, and with Mg-proto bound, using

CD (Fig. 2). BchM showed changes in the Soret region

of Mg-proto when bound to BchM, but there was no

obvious change in the far-UV region (Fig. 1 and

Table S1). The differences in the Soret region upon

Mg-proto binding to BchM signifies disymmetric

changes in porphyrin planarity. Therefore, it is sug-

gested that binding of Mg-proto to BchM distorts the

planarity of Mg-proto, causing the prominent signal in

the Soret CD region, similar to what is observed when

apomyoglobin is reconstituted with hemin [43]. In con-

trast, BchJ showed no structural changes upon binding

Mg-proto in the Soret region; however, significant

differences were observed in the CD spectra of

the far-UV region. The changes in the far-UV region

were seemingly inversely related, with a decrease in

b-strands (20.8% to 6.2%) being balanced by an

increase in regular a-helices (34% to 47%) (Table S1).

Thus, in comparison with BchM, BchJ showed a com-

paratively malleable secondary structure, with the

changes presumably being needed to accommodate

Mg-proto, as the porphyrin did have an induced chirality

detectable by CD when bound to the BchJ. This suggests

that the binding is specific and strains the porphyrin

in a similar manner as observed for myoglobin [43].

Interaction between magnesium chelatase and

BchM, BchJ or Tween-80

Previous findings have consistently shown that the

BchH subunit of magnesium chelatase enhances O-

methyltransferase activity in C. tepidum,Synechocystis,

R. capsulatus and tobacco [11,38–40,44], implying that

O-methyltransferase accepts the Mg-proto substrate

when bound to BchH. We found that BchM could uti-

lize Mg-proto produced in situ from BchH, with Mg-

proto monomethyl ester being made in the complete

coupled assay (BchIDHM SAM) (Fig. S3). Mg-proto

remains tightly bound to R. capsulatus BchH in the

magnesium chelatase reaction [15], and exchanges

slowly with exogenous proto [18]. BchM converts all of

the Mg-proto produced in a magnesium chelatase reac-

tion into the methyl ester (Fig. S3), and also shifts the

magnesium chelatase equilibrium, whether or not

methylation occurs (Figs 6, 7 and 8). To do both,

BchM must either release the Mg-proto from BchH or

stabilize the Mg-proto while it is bound to BchH. Dis-

tinguishing between these two possibilities with, for

example gel, filtration was not possible, owing to the

aggregation of BchM in magnesium chelatase assay

buffer. To more accurately quantify the respective

interactions of BchM, BchJ or Tween-80 with BchH,

we focused on their kinetic effects in a magnesium

chelatase assay, because our previous findings could

not establish a unique stimulatory effect of magnesium

chelatase subunits on O-methyltransferase activity [32].

It was initially found that BchM, BchJ or Tween-80

generated an increased amount of Mg-proto produced

by magnesium chelatase over time, and the time taken

to reach equilibrium was significantly faster for BchM

than for BchJ and Tween-80 (Fig. 6). Our subsequent

A

B

Fig. 4. Coprecipitation of magnesium chelatase subunits with

BchM or BchJ; distribution of protein into soluble and insoluble

fractions. M refers to the Bio-Rad broad-range ladder, with molecu-

lar masses in kilodaltons listed on the left-hand side. 1, BchIDH;

2, BchIDHM; 3, BchIDHJ; 4, BchIDH and Tween-80. Assays were

performed as described for magnesium chelatase, with final con-

centrations of 86 mMglycerol, 18 mMurea, 4 mMdithiothreitol,

0.33 lMBchD, 0.66 lMBchI, 1.385 lMBchH–proto and, if present,

2.7 lMBchM ⁄BchJ or 117 lMTween-80 in a total volume of

160 lL. The total assay time was 90 min; the assay was followed

by centrifugation at 18 000 gfor 7 min at room temperature to sep-

arate supernatant and pellet fractions. A total volume of 25 lLof

supernatant was loaded onto a 4–15% polyacrylamide gel (Bio-Rad)

(A). The pellet fraction was further washed twice 100 lL of assay

buffer without protein or detergent, vortexed for 10 s, and centri-

fuged after each wash step with the supernatant of each wash dis-

carded. The final pellet was resuspended in 25 lL of SDS ⁄PAGE

loading buffer (Nu-Sep), and the total volume was loaded onto the

gel (B). The approximate position of each protein is listed on the

right-hand side.

A. Sawicki and R. D. Willows Interaction of BchM ⁄BchJ with magnesium chelatase

FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 4709–4721 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS 4713