Hyperthermal stability of neuroglobin and cytoglobin

Djemel Hamdane

1

, Laurent Kiger

1

, Sylvia Dewilde

2

, Julien Uzan

1

, Thorsten Burmester

3

,

Thomas Hankeln

4

, Luc Moens

2

and Michael C Marden

1

1 Inserm U473, Le Kremlin-Bice

ˆtre, France

2 Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Antwerp, Belgium

3 Institute of Zoology, Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz, Germany

4 Institute of Molecular Genetics, Johannes Gutenberg University of Mainz, Germany

Neuroglobin (Ngb) and cytoglobin (Cygb) have been

identified recently [1–3] as new globins in vertebrates.

Ngb is predominately expressed in certain regions of

the brain as well as in some endocrine tissues [1,4] and

at a higher level in the retina [5], whereas Cygb is

expressed in all tissues. Although sequence analysis

reveals little similarity with hemoglobin (Hb) and myo-

globin (Mb), Ngb and Cygb share many of the charac-

teristics of the globins such as reversible oxygen

binding and the overall three-dimensional globin fold

[6–8]. In the absence of external ligands such as oxy-

gen, Ngb and Cygb are hexa-coordinated with a bis-

histidyl heme [9].

The primary functions of Ngb and Cygb remain

unknown, but some hypotheses have been suggested

[9–11]. Expression of Ngb increases in cultures of neu-

rons under hypoxic conditions, and it appears that Ngb

may protect cells against hypoxia [12,13]. Thus Ngb

may have a Mb-like function, supplying the respiratory

chain of neuronal mitochondria with O

2

[1,5]. Cygb

may be a signaling or sensor protein [14], and may be

involved in collagen synthesis or in the protection

against reactive oxygen species [15]. Other physiological

roles, however, such as electron transfer, peroxidase

activity, NO binding or NO detoxification, as observed

for other hemoproteins, are still conceivable.

Unique in the globin family, Ngb and Cygb possess

cysteine residues capable of forming a disulfide bond

[16]. Reduction of the disulfide bond in Ngb increases

the affinity for the distal histidine by a factor of nearly

Keywords

cytoglobin; disulfide bond; ligand kinetics;

neuroglobin; protein melting temperature

Correspondence

M. C. Marden, Inserm U473, 78 rue du

General Leclerc, 94275 Le Kremlin-Bice

ˆtre,

France

E-mail: marden@kb.inserm.fr

(Received 6 December 2004, revised 14

February 2005, accepted 1 March 2005)

doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04635.x

Neuroglobin (Ngb) and cytoglobin (Cygb), recent additions to the globin

family, display a hexa-coordinated (bis-histidyl) heme in the absence of

external ligands. Although these proteins have the classical globin fold they

reveal a very high thermal stability with a melting temperature (T

m

)of

100 C for Ngb and 95 C for Cygb. Moreover, flash photolysis experi-

ments at high temperatures reveal that Ngb remains functional at 90 C.

Human Ngb may have a disulfide bond in the CD loop region; reduction

of the disulfide bond increases the affinity of the iron atom for the distal

(E7) histidine, and leads to a 3 C increase in the T

m

for ferrous Ngb. A

similar T

m

is found for a mutant of human Ngb without cysteines. Appar-

ently, the disulfide bond is not involved directly in protein stability, but

may influence the stability indirectly because it modifies the affinity of the

distal histidine. Mutation of the distal histidine leads to lower thermal sta-

bility, similar to that for other globins. Only globins with a high affinity of

the distal histidine show the very high thermal stability, indicating that sta-

ble hexa-coordination is necessary for the enhanced thermal stability; the

CD loop which contains the cysteines appears as a critical region in

the neuroglobin thermal stability, because it may influence the affinity of

the distal histidine.

Abbreviations

Cygb, cytoglobin; GdmCl, guanidinium chloride; Hb, hemoglobin; Mb, myoglobin; Ngb, neuroglobin; T

m

, melting temperature.

2076 FEBS Journal 272 (2005) 2076–2084 ª2005 FEBS

10; it has therefore been hypothesized that reduction

of the SS bridge may promote oxygen release [16].

Proteins, and particularly enzymes, are generally

quite sensitive to environmental changes, e.g. elevated

temperatures, due to highly cooperative unfolding [17].

However, there are some exceptions such as those

found in extreme thermophilic microorganisms. Com-

parison of the protein structure from mesophiles and

thermophiles has allowed some explanation of thermo-

stability based on small solvent-exposed surface area

[18], increased packing density [19–21], core hydro-

phobicity [22], decreased surface loop length [21], and

the generation of salt bridges or hydrogen bonds

betweens polar residues [23–25]. The affinity of apo-

globin for heme or the orientation of the heme in the

pocket cavity may play a major role in the stability of

the holoprotein [26]. In general, few proteins are stable

above 80 C; examples are calcium-binding proteins

such as calmodulin or troponin C with T

m

>90C

for the Ca-bound form [27].

Results

Spectroscopy

The visible spectrum of dithionite-reduced Ngb, Cygb,

and Drosophila Hb showed characteristic absorption

maxima of hexa-coordinated (bis-histidyl) species [3,9,

28]. We observed enhanced absorption of the alpha

band at 560 nm, a signature of the hexa-coordinated

form.

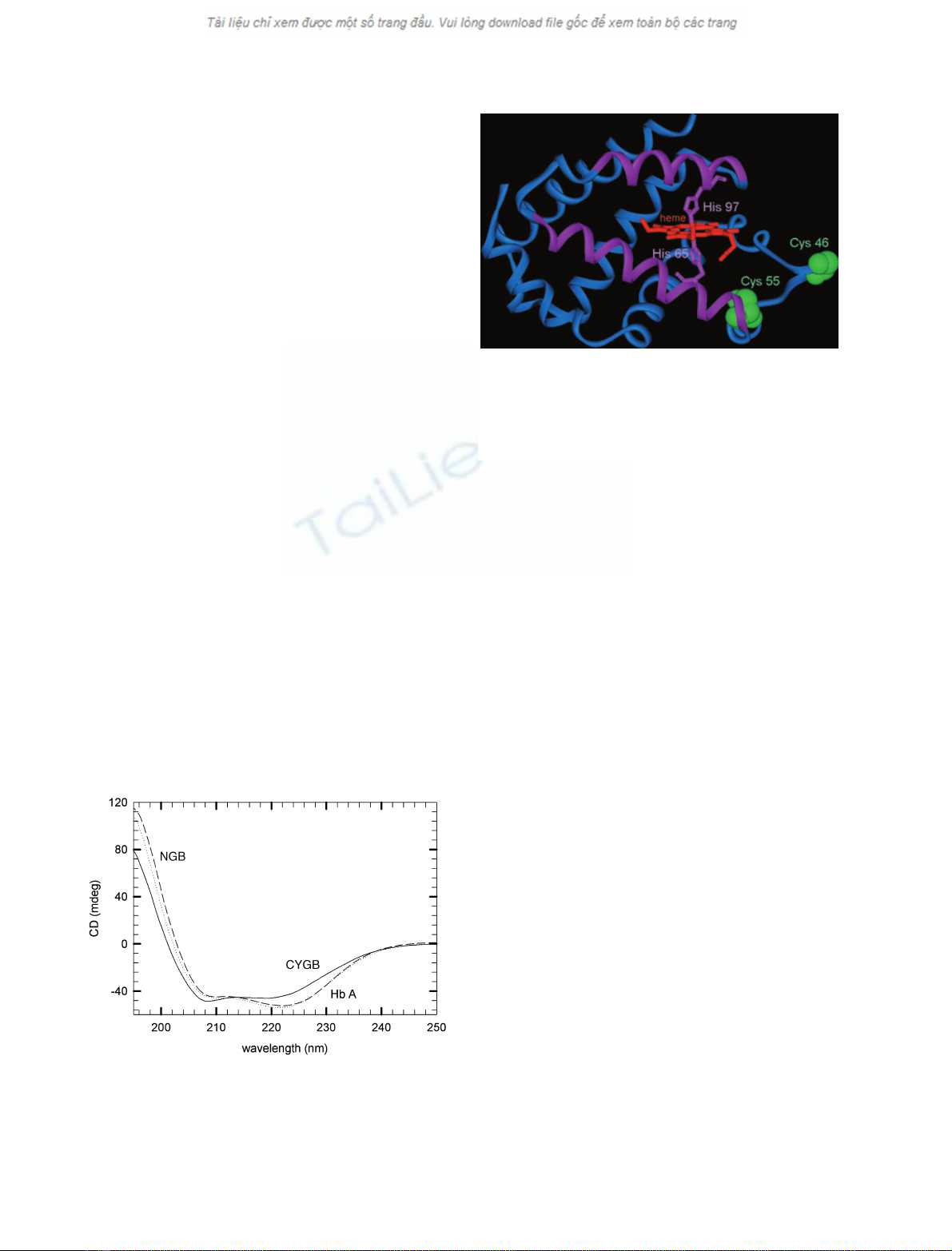

The far-ultraviolet circular dichroism spectrum (190–

250 nm) of ferric Ngb was typical of the globin family

(Fig. 1) showing mainly an alpha helical secondary

structure, in agreement with the X-ray structure [6].

The spectra for native Ngb had negative bands at 208

and 222 nm (Fig. 1), as expected for a high percentage

of alpha helix. Analysis of the secondary structure of

Ngb gave 78% alpha helix and 22% of other forms,

similar to HbA which was used as a control. The spec-

trum for Cygb showed slightly less alpha helix, as

expected if the extra residues (20 at each extremity)

are not helical.

Human Ngb has cysteine residues at positions 46

(CD7), 55 (D5) and 120 (G19). The cysteines CD7 and

D5 (Fig. 2), may form a disulfide bond within the CD

loop [16]. However, in mouse Ngb there are only two

cysteine residues (D5 and G19) and thus no intradisul-

fide bond is present. A similar circular dichroism spec-

trum was observed for mutant Ngb without cysteine

residues (triple mutation C46G C55S C120S, which we

refer to as CCC fiGSS), and for the mutant with

modified distal (E7) residue (data not shown). These

experiments suggest that the wild-type and mutant Ngb

proteins are correctly folded to the structure typical of

globins.

Thermal denaturation

Changes in the far-UV circular dichroism signal at

222.6 nm were used to follow the thermal unfolding.

The circular dichroism spectra vs. temperature revealed

a high thermal stability for Ngb and Cygb. The melt-

ing profiles are shown in Figs 3–6.

The melting temperature (T

m

) for human Ngb was

100 C for the ferrous form, 20 C higher than that

for horse heart myoglobin (Mb). The mutant of

Fig. 1. Circular dichroism spectra in the far-UV region of human

Ngb (…), human Cygb (——), and human HbA (– – –) at 25 Cin

1m

Mphosphate buffer at pH 7.

Fig. 2. Crystallographic structure of human Ngb mutant CCC fi

GSS (6). The hexa-coordination by the E7 (65) and F8 (97) histidines

helps stabilize the protein. The sites for the cysteines (CD7 and D5)

are shown in green; the disulfide bond (which decreases the E7

histidine affinity) decreases the melting temperature slightly, indica-

ting an indirect effect on the stability.

D. Hamdane et al. Thermal stability of neuroglobin

FEBS Journal 272 (2005) 2076–2084 ª2005 FEBS 2077

human Ngb without cysteines (CCC fiGSS) or sam-

ples of Ngb with dithiothreitol (to break the disulfide

bond, Fig. 3) or mouse Ngb (which does not have the

internal disulfide bond) had a T

m

value > 100 C

(Table 1). This would suggest that Ngb without the di-

sulfide bond is the most stable form. Because loss of

the disulfide bond in human Ngb increases the affinity

of the distal histidine (Table 1), the protein stability

may depend more directly on the hexa-coordination

rather than the disulfide bond.

The state of the iron atom may also influence T

m

(Fig. 4). For all species studied, we observed that the

deoxy form was the most stable (Table 1). The T

m

value of the deoxy ferrous species was obtained after

incubation of protein in dithionite under nitrogen.

Note that a rapid autoxidation at high temperatures

may prevent measurements on samples that remain

fully ferrous. The fact that ligands CO or CN

–

decrease the T

m

also suggests that the most stable form

is that in which the protein forms a sort of clamp

Fig. 3. Effect of the cysteine bridge of human Ngb on the thermal

stability. The melting temperature, corresponding to the peak of

this curve of the first derivative of the circular dichroism signal vs.

temperature, is shifted to higher values when the disulfide bond is

broken with dithiothreitol or for the mutant without cysteines.

Experiments were performed in 10 mMphosphate at pH 7 for ferric

human Ngb (d), Ngb with 0.5 mMdithiothreitol under nitrogen (j),

and the ferric mutant (CCC fiGSS) without cysteines (– –).

mouse Ngb

Temperature (°C)

80 85 90 95 100 105

fu

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

ferrous

ferrous

CO

ferric-CN ferric

Fig. 4. Melting profiles (fraction unfolded f

U

vs. temperature) of

mouse Ngb for different ligation states. Experimental conditions

were 1 mMphosphate buffer at pH 7 (at 25 C). Smooth curves are

simulations for a two state transition, as described in Experimental

procedures.

Temperature (°C)

60 70 80 90 100

fU

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

Cygb Ngb

Ngb

CCC->GSS

Mb

Drosophila

Fig. 5. Melting profiles of ferric hexa-coordinated globins. The frac-

tion unfolded f

U

vs. temperature is shown for Drosophila Hb (r),

Mb (d), human Ngb (m), the mutant CCC fiGSS of human Ngb

(.) and Mb (d). Experimental conditions were 1 mMphosphate

buffer at pH 7 (at 25 C).

[Guanidinium-chloride] (M)

0.0 0.5 1.0 1.5 2.0 2.5

Tm (°C)

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

wt CCC->GSS

40 60 80 100

0.0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1.0

temperature (°C)

f

U

2M 1M

0.5M

human Ngb

Fig. 6. Dependence of the melting temperature T

m

on [guanidinium

chloride] for wt human Ngb and the triple mutant CCC fiGSS. The

T

m

(Table 1) was obtained by extrapolation to 0 Mof guanidinium

chloride. The insert shows the thermal unfolding curve of human

Ngb at three concentrations of guanidinium chloride, in 10 mM

phosphate at pH 7.

Thermal stability of neuroglobin D. Hamdane et al.

2078 FEBS Journal 272 (2005) 2076–2084 ª2005 FEBS

around the heme group via the bis-histidyl binding to

the heme group. Furthermore, the decrease in T

m

upon

binding the external ligand could be underestimated at

high temperature due to oxidation or loss of the exter-

nal ligand.

Cygb and the globin from Drosophila are also hexa-

coordinated [2,3,28] and show various degrees of

enhanced stability (Fig. 5, Table 1). Cygb has an affin-

ity for the distal histidine 2.5-fold lower than human

Ngb and exhibits a T

m

5C lower than human Ngb.

A similar, but larger, effect was observed for the glo-

bin of Drosophila, in which the affinity of the distal

histidine is 14 times lower and the T

m

is decreased by

24 C relative to human Ngb. The very high stability

requires the hexa-coordinated state; for these cases the

T

m

may exceed 100 C, and additional curves were

measured at different concentrations of guanidinium

chloride (Fig. 6) to better determine the T

m

value.

Replacement of the distal histidine by valine, leucine

or glutamine in mouse Ngb leads to a loss of the

enhanced alpha absorption band in the deoxy form,

characteristic of the internal residue coordination (data

not shown). Relative to wild-type mouse Ngb, the sin-

gle mutation E7L in mouse Ngb caused a decrease of

20 C in thermostability, again suggesting a critical role

for His E7 in the enhanced thermal stability of Ngb.

Certain mutations of the distal histidine in Mb and Hb

lead to instability linked to a higher autoxidation rate

and ⁄or heme loss. Note that the E7 mutants are stable

with regard to O

2

binding, indicating that the mutation

does not affect the pocket to a large extent.

Reversibility

Although the thermal denaturation was irreversible for

human Hb, we observed a significant thermal reversi-

bility for mouse and human Ngb, and human Cygb.

The loss in helical content was 15%, estimated by the

difference at 222 nm between the initial and final circu-

lar dichroism spectra at 25 C after the temperature

cycle to 100 C (data not shown). The reversibility was

also tested by the absorption spectra (Fig. 7) and by

flash photolysis kinetics (Fig. 8). Ngb maintains a high

Table 1. Melting temperature (T

m

) and histidine affinity (K

His

¼

k

on

⁄k

off

) for hexa-coordinated globins.

T

m

(C) K

His

K

CN–,Mb

⁄K

CN–

Disulfide bond

Human Ngb (yes) 100 280

Human Ngb + dithiothreitol (no) 103 3300

Human Ngb CCC fiGSS (no) 103 4500

Ferric human Ngb (yes) 97 45

Ferric human Ngb CCC fiGSS (no) 101 428

Iron state

Ferrous mouse Ngb CO 95

Ferric mouse Ngb CN

–

94

Ferrous mouse Ngb (His) 103 2000

Ferric mouse Ngb (His) 100 137

Variable (E7) His affinity

Human Ngb CCC fiGSS 103 4500

Human Ngb (with disulfide bond) 100 280

Human Cygb 95 110

Drosophila Hb 76 18

Mouse Ngb His (E7) fiLeu 80 _

Horse heart Mb 81 < < 1

Human HbCO 71 < < 1

Fig. 7. Absorption spectra of ferrous human Ngb with dithiothreitol

(to break the disulfide bridge) at 25 C (solid line), after 5 min incu-

bated at 90 C, and finally at 25 C after the temperature cycle (s).

The spectrum for ferric human Ngb (with Soret band at 413 nm) is

also shown.

time (sec)

10

-6

10

-5

10

-4

10

-3

10

-2

10

-1

0.1

1

∆

A

N

human Ngb-CO

25°C

50°C

70°C

90°C

Fig. 8. Ligand rebinding kinetics for human Ngb at temperatures

from 25 to 90 C for samples equilibrated under 0.1 atm (100 lM)

CO, in 100 mMphosphate buffer at pH 7.

D. Hamdane et al. Thermal stability of neuroglobin

FEBS Journal 272 (2005) 2076–2084 ª2005 FEBS 2079

percentage (85%) of its initial characteristics after

the temperature cycle, whereas Mb shows 70%; the

fraction of functional HbA after the temperature cycle

was only 20%.

The shape of thermal denaturation curves of the

various globins may differ, suggesting different mecha-

nisms or degrees of cooperativity for the unfolding

transition. Classical denaturation between two states

results a cooperative denaturation with a maximum

slope at T

m

. The enthalpy of denaturation DH

m

of

Ngb and horse heart Mb was 72 and 110 kcalÆmol

)1

,

respectively. Cytoglobin and the globin of Drosophila

have lower values of DH

m

, 60 and 53 kcalÆmol

)1

,

respectively. Note that human Hb and Cygb are tetra-

meric and dimeric, respectively, and may involve a

more complicated mechanism including subunit disso-

ciation.

Ligand-binding kinetics

The circular dichroism spectra show that the protein is

still correctly folded at elevated temperatures, but do

not provide much information about protein function.

We studied ligand binding using flash photolysis to see

whether Ngb was functional at extreme temperatures.

The kinetics after CO photodissociation showed a bi-

phasic curve. The rapid phase corresponds to compet-

itive CO and His E7 association, whereas the slower

phase is the replacement of the E7 His by CO.

The kinetics for human Ngb at different tempera-

tures, up to 90 C, are shown in Fig. 8. The kinetic

curves show a steady progression vs. temperature, indi-

cating that there is no major change in the basic ligand-

binding properties. The increase in temperature leads to

an increase in the amplitude of the slow phase, indica-

ting that higher temperatures favor His vs. CO rebind-

ing; that is, the histidine association rate (k

His,on

) has a

higher activation energy than that for CO (Table 2).

Competition with the internal histidine ligand

decreases the affinity for external ligands such as CO:

KCO;obs ¼KCO;penta

1þKHis

¼kCO;on=kCO;off

1þkHis;on=kHis;off

ð1Þ

From the kinetic curves vs. [CO], one can extract three

of the rate parameters; the CO off rate must be deter-

mined independently. Equilibrium studies allow an

independent measure of the shift in observed affinity

due to the histidine.

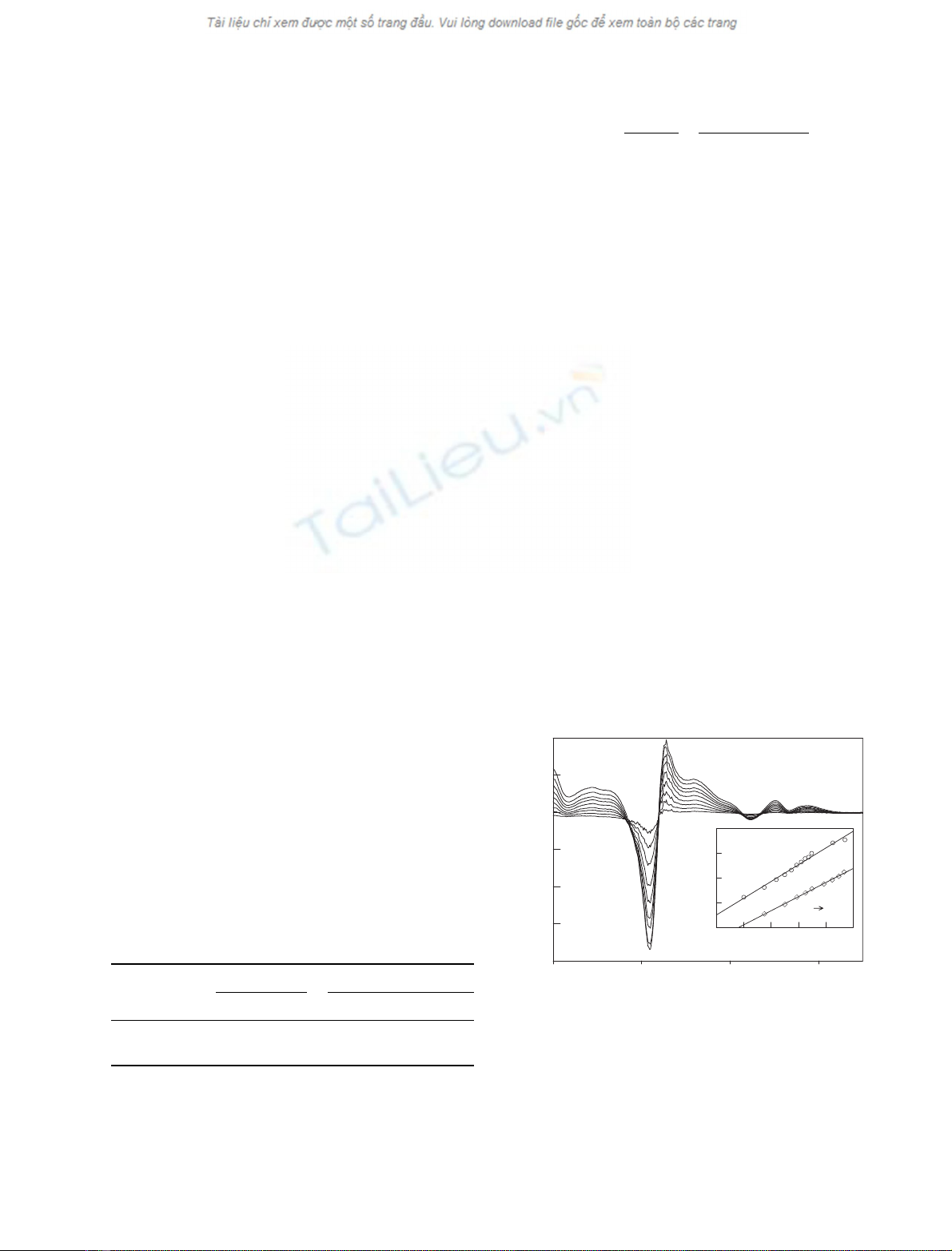

Cyanide affinity

The absorption difference spectrum in the visible

region of ferric Ngb and cyanide derivative are shown

Fig. 9. The maximum absorption of ferric Ngb occurs

at 413 nm (Fig. 7). Cyanide binding to ferric Ngb

leads to a red shift in the Soret band; peak absorption

is seen at 416 nm for the mutant Ngb without cyste-

ines, and 417 nm for species with the disulfide bond.

The fraction saturation was calculated from the spec-

tral difference, and the titration curve (Fig. 9 insert)

gives a linear Hill plot.

The affinity of cyanide for ferric Ngb was much

lower than for Mb (Table 1), indicating competition

by the distal histidine, as in the ferrous form. The

affinity for cyanide was higher for mutant forms with-

out the distal histidine. For human Ngb without cys-

teine residues, the CN

–

affinity was lower, suggesting a

higher affinity for the competing histidine, as observed

in the ferrous form. Based on the shift in the CN

–

affinity, one can estimate the histidine affinity for the

Table 2. Activation and binding energies for CO binding to human

Ngb.

Species

His (kcalÆmol

)1

) CO (kcalÆmol

)1

)

E

on

E

off

DEE

on

E

off

DEDE

obs

Human Ngb 11 24 13 5.5 10 4.5 )9.5

a

Horse heart Mb 7.5 16 8.5 8.5

a

A value of )10 (± 3) kcalÆmol

)1

was determined from equilibrium

studies. Experimental conditions were 100 mMphosphate buffer at

pH 7.0, in the presence of 5 mMdithiothreitol.

wavelength (nm)

300 400 500 600

∆A

-0.20

-0.15

-0.10

-0.05

0.00

0.05

0.10

LOG(KCN µM)

1.6 2.0 2.4 2.8 3.2 3.6

LOG (Y/1-Y)

-2

-1

0

1

2

human Ngb

CCC GSS

428 nm

409 nm

wt

Fig. 9. Absorption difference spectra at various cyanide concentra-

tions, relative to the ferric Ngb form (without cyanide). The spectra

were measured at room temperature in 100 mMpotassium phos-

phate at pH 8. The insert shows the Hill plot of cyanide binding to

ferric Ngb. The shift to a lower CN

–

affinity for Ngb without the

disulfide bond is similar to that for oxygen in the ferrous form.

Thermal stability of neuroglobin D. Hamdane et al.

2080 FEBS Journal 272 (2005) 2076–2084 ª2005 FEBS