The role of evolutionarily conserved hydrophobic contacts

in the quaternary structure stability of Escherichia coli

serine hydroxymethyltransferase

Rita Florio

1

, Roberta Chiaraluce

1

, Valerio Consalvi

1

, Alessandro Paiardini

1

, Bruno Catacchio

1,2

,

Francesco Bossa

1,3

and Roberto Contestabile

1

1 Dipartimento di Scienze Biochimiche ‘A. Rossi Fanelli’, ‘Sapienza’ Universita

`di Roma, Italy

2 CNR, Istituto di Biologia e Patologia Molecolari, ‘Sapienza’ Universita

`di Roma, Italy

3 Centro di Eccellenza di Biologia e Medicina Molecolare (BEMM), ‘Sapienza’ Universita

`di Roma, Italy

Pyridoxal 5¢-phosphate (PLP)-dependent enzymes are a

large ensemble of biocatalysts that make use of the

same cofactor but have distinct evolutionary origins

and protein architectures [1–3]. According to their 3D

structure, PLP-dependent enzymes are grouped into

five evolutionarily unrelated superfamilies, correspond-

ing to as many different folds (fold types) [4]. The fold

type I group, also referred to as the aspartate amino-

transferase family [5], is the largest, functionally most

diverse and best characterized. Its members are catal-

ytically active as homodimers, although they may

assemble into higher order complexes. A single subunit

folds into two domains [6]. The central feature of the

N-terminal, larger domain is a seven-stranded b-sheet.

In some instances, the N-terminal tail does not partici-

pate as a part of the large domain but comprises a

separate structural element. The small, C-terminal

domain, comprises a three- or four-stranded b-sheet,

covered with helices on one side. The active site is

located at the interface of the domains and is delimited

by amino acid residues that are contributed by

both subunits of the catalytic dimer. Remarkably, the

Keywords

conserved hydrophobic contacts; fold type I

enzymes; pyridoxal phosphate; quaternary

structure; serine hydroxymethyltransferase

Correspondence

R. Contestabile, Dipartimento di Scienze

Biochimiche, ‘Sapienza’ Universita

`di Roma,

Piazzale Aldo Moro 5, 00185 Rome, Italy

Fax: +39 0649 917566

Tel: +39 0649 917569

E-mail: roberto.contestabile@uniroma1.it

Website: http://w3.uniroma1.it/bio_chem/

sito_biochimica/EN/index.html

(Received 18 September 2008, revised 23

October 2008, accepted 27 October 2008)

doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2008.06761.x

Pyridoxal 5¢-phosphate-dependent enzymes may be grouped into five struc-

tural superfamilies of proteins, corresponding to as many fold types. The

fold type I is by far the largest and most investigated group. An important

feature of this fold, which is characterized by the presence of two domains,

appears to be the existence of three clusters of evolutionarily conserved

hydrophobic contacts. Although two of these clusters are located in the

central cores of the domains and presumably stabilize their scaffold, allow-

ing the correct alignment of the residues involved in cofactor and substrate

binding, the role of the third cluster is much less evident. A site-directed

mutagenesis approach was used to carry out a model study on the impor-

tance of the third cluster in the structure of a well characterized member

of the fold type I group, serine hydroxymethyltransferase from

Escherichia coli. The experimental results obtained indicated that the clus-

ter plays a crucial role in the stabilization of the quaternary, native assem-

bly of the enzyme, although it is not located at the subunit interface. The

analysis of the crystal structure of serine hydromethyltransferase suggested

that this stabilizing effect may be due to the strict structural relation

between the cluster and two polypeptide loops, which, in fold type I

enzymes, mediate the interactions between the subunits and are involved in

cofactor binding, substrate binding and catalysis.

Abbreviations

CHC, conserved hydrophobic contact; eSHMT, Escherichia coli serine hydroxymethyltransferase; H

4

PteGlu, tetrahydropteroylglutamate; PLP,

pyridoxal 5¢-phosphate; SCR, structurally conserved region.

132 FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 132–143 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS

superimposition of fold type I enzymes reveals that the

location of the cofactor in the active site is virtually

identical in all members of the group [7].

Despite the high similarities of their 3D structures,

many fold type I enzymes show very little sequence

identity, highlighting the need to identify the structural

features that determine the common fold. Accordingly,

a computational analysis that made use of 23 nonre-

dundant crystal structures and 921 sequences of fold

type I enzymes identified 17 structurally conserved

regions (SCRs), which form the common cores of the

large and small domains. Within these SCRs, there are

three clusters of evolutionarily conserved hydrophobic

contacts (CHCs) [8]. The first and second cluster are

located in the cores of the large and small domains,

respectively, and appear to stabilize their protein scaf-

folds, allowing the proper positioning of the residues

involved in PLP binding, substrate binding and modu-

lation of the cofactor’s catalytic properties. The third

cluster forms a hinge between two conserved a-helices

(which correspond to two SCRs), located at the begin-

ning and at the end, respectively, of the large domain

(Fig. 1). Examination of the contact network shows

that the CHCs lie along one side of each helix, forming

a buried spine at positions i,i+ 4, and i+7. By

apparent contrast to the two previously described clus-

ters, the third cluster does not appear to be directly

involved in the proper positioning of any active site

residue, suggesting that its high degree of evolutionary

conservation could be due to a merely structural,

rather than functional role.

In the present study, the importance of the third

hydrophobic cluster as a structural determinant of the

Escherichia coli serine hydroxymethyltransferase

(eSHMT) overall native fold was investigated by

decreasing the hydrophobic contact area of the cluster,

using a site-directed mutagenesis approach. The effects

of L85A, L276A and L85A ⁄L276A mutations on the

native structure of the enzyme were analyzed (Fig. 1).

Results

The consequences of the mutations on the native struc-

ture of eSHMT were evaluated by analyzing and

comparing the ultracentrifuge sedimentation, cofactor

binding, catalytic and spectral properties of wild-type

and mutant apo- and holoenzymes.

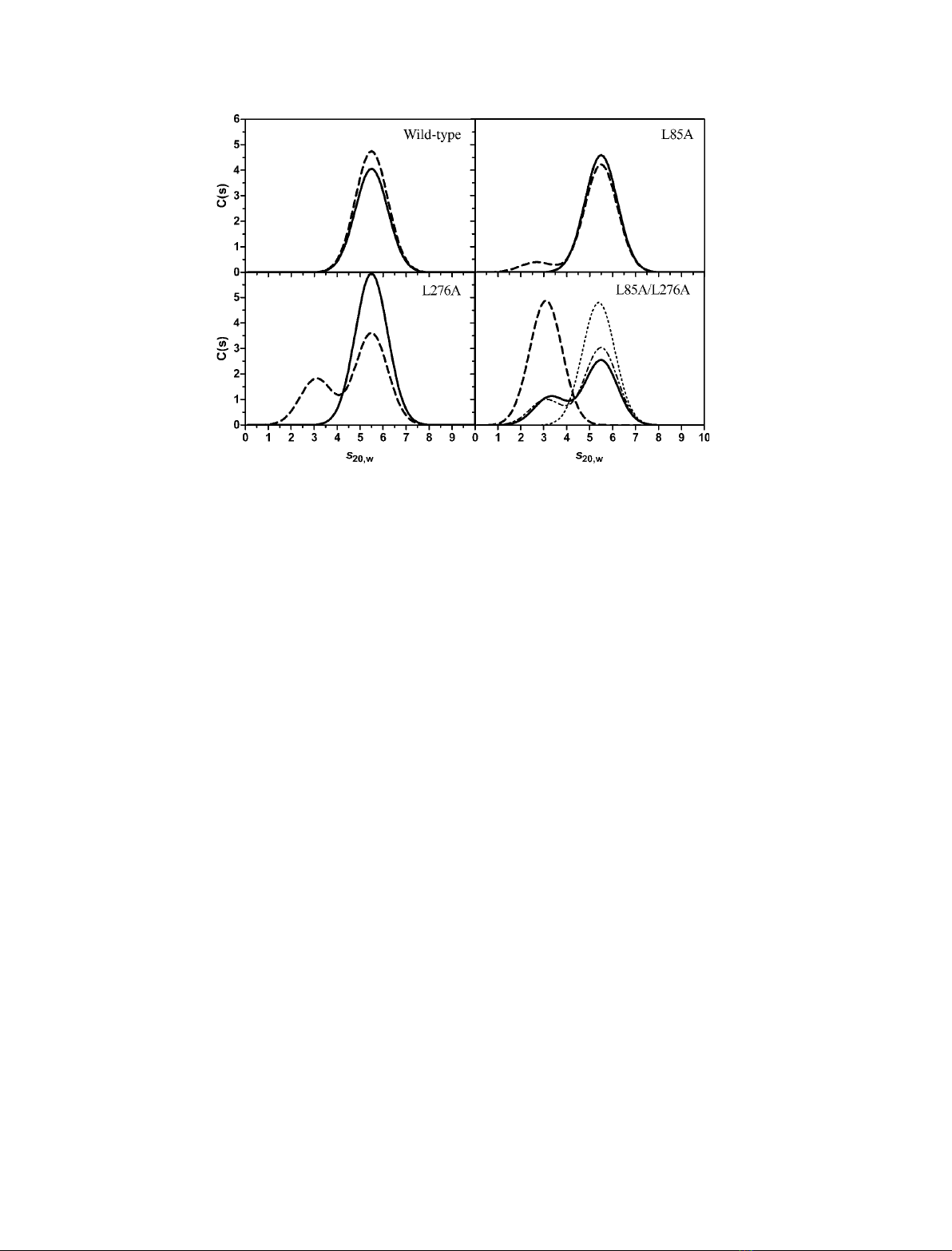

Quaternary structure analysis

The subunit assembly of apo- and holo-forms of wild-

type and mutant eSHMTs was characterized by analyt-

ical ultracentrifugation. Table 1 shows the values of

sedimentation coefficient and dissociation constant

(K

d

) calculated from combined sedimentation velocity

and equilibrium approaches. As established in the

available literature [9,10], wild-type eSHMT exists as a

dimer in both apo- and holo-forms, with a molecular

mass of approximately 91 kDa [9]. The ultracentrifuga-

tion experiments confirmed that the depletion of the

cofactor does not have any effect on the dimeric

assembly of the enzyme. The sedimentation velocity

Fig. 1. Schematic representation of the monomeric structure of eSHMT. Cartoon representation of a single subunit of the eSHMT ternary

complex with glycine and 5-formyl H

4

PteGlu (Protein Data Bank: 1dfo) [14], showing the N-terminal tail (residues 1–61) colored in orange,

the large domain (residues 62–211) in salmon, the interdomain segment (residues 212–279) in green and the small domain in blue. The PLP-

Gly complex is shown as yellow sticks, with the phosphorus atom in orange, the oxygen atoms in red and the nitrogen atoms in blue. The

two a-helices involved in the formation of the third cluster of CHCs are enclosed in a circle. A magnified view of these helices shows the

residues that form the CHCs represented both as sticks and as transparent spheres. L85 and L276 are indicated by arrows.

R. Florio et al. Role of hydrophobic contacts in serine hydroxymethyltransferase

FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 132–143 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS 133

patterns of apo- and holo-forms are indeed almost

superimposable, with a single symmetrical peak char-

acterized by a sedimentation coefficient, S

20,w

, of 5.5S

(Fig. 2), which is the value expected for a hydrated

eSHMT dimer endowed with an approximately spheri-

cal shape. The sedimentation equilibrium experiments

showed that, in the 2.5–25 lmsubunit concentration

range, the wild-type eSHMT is a dimer, either in the

presence or absence of cofactor. In the same concen-

tration range, the L85A and L276A mutant holoen-

zymes are also dimers, with sedimentation coefficients

of 5.5S. Interestingly, the frictional ratio (f⁄f

0

, the ratio

between the experimentally calculated friction coeffi-

cient and the minimum friction coefficient of an anhy-

drous sphere) of dimeric wild-type, L85A and L276A

eSHMT holoenzymes is close to that of a spherical

protein, namely 1.2–1.3, suggesting that the single

mutations did not result in significant changes in the

shape of the dimeric protein.

Depletion of the cofactor affected the quaternary

structure of both single mutants, which showed an

extra sedimentation peak, at approximately 2.7S in the

case of L85A and at 3.1S with the L276A mutant

(Fig. 2). The smaller sedimentation coefficient corre-

sponds to that of monomeric eSHMT. Therefore, the

single mutant apoenzymes exist as an equilibrium mix-

ture of dimers and monomers, which interconvert

slowly with respect to the period of elapsed time in the

sedimentation velocity experiments. A comparison of

the dissociation constants of the single mutant apo-

forms, obtained by a fitting of the sedimentation equi-

librium curves to a monomer-dimer model, indicates

that the destabilizing effect of PLP depletion is greater

in L276A (K

d

= 2.7 ·10

)6

m

)1

) than in L85A

(K

d

= 4.0 ·10

)9

m

)1

). When both mutations are pres-

ent, as in the L85A ⁄L276A double mutant, the apoen-

zyme exists as a monomer in the range of

concentrations tested (2.5–25 lm). The frictional ratio

of this monomeric species was calculated to be approx-

imately 1.2, suggesting that the dissociation determined

by the double mutation was not accompanied by large

structural changes.

Compared to that observed with the single L85A

and L276A mutants, cofactor binding to the

L85A ⁄L276A double mutant apoenzyme did not shift

the equilibrium completely in favor of the dimer. In

the double mutant holoenzyme, obtained by adding

PLP to 98% of saturation (as calculated from the dis-

sociation constant of the related cofactor binding equi-

librium; see below), a residual 35% fraction of

monomer is in equilibrium with the dimer (Table 1

and Fig. 2). A dissociation constant of 1.7 ·10

)6

m

)1

was calculated for this equilibrium. Because it is

known that PLP bound to eSHMT through a Schiff

base linkage to the active site lysine residue absorbs

light maximally at 420 nm [9], a sedimentation velocity

experiment was performed on a double mutant holoen-

zyme sample (33 lm), measuring absorbance at this

wavelength. The presence of a 3.1S peak in the sedi-

mentation pattern indicated that the cofactor was

covalently bound to the monomeric form of the

enzyme (Fig. 2). The lower percentage of monomer

present in this sedimentation profile (12% instead of

35%; Fig. 2 and Table 1) is accounted for by the

higher concentration of enzyme employed in the exper-

iment, and as calculated by using the equation describ-

Table 1. Sedimentation and dissociation constants calculated from

ultracentrifuge experiments on apo- and holo-forms of wild-type

and mutant eSHMTs.Values are shown of the S

20,w

sedimentation

coefficient calculated in sedimentation velocity experiments on

enzyme samples at 2.5 lMsubunit concentration, in 50 mM

NaHepes buffer (pH 7.2), containing 200 lMdithiothreitol and

100 lMEDTA, at 20 C. Percentages in parenthesis correspond to

the fraction of enzyme subunits that sediment with the related

coefficient and were calculated from an integration of the sedimen-

tation profiles shown in Fig. 2. The dissociation constants of dimer–

monomer equilibria (K

d

) were determined from sedimentation

equilibrium experiments carried out on enzyme samples in the

2.5–25 lMsubunit concentration range.

S

20, w

(S) K

d

(M

)1

)

a

Holoenzyme forms

WT 5.5 ND

L85A 5.5 ND

L276A 5.5 ND

L85A ⁄L276A 5.5 (66%) 3.3 (34%)

5.5 (88%)

b

3.1 (12%)

b

1.7 ·10

)6

Apoenzyme forms

WT 5.5 ND

L85A 5.5 (90%)

c

2.7 (8%)

c

4.0 ·10

)9

L276A 5.5 (65%) 3.1 (35%) 2.7 ·10

)6

L85A ⁄L276A 3.1 ND

a

Dissociation constants could not be calculated for wild-type and

single mutant holoenzymes and for the double mutant apoenzyme

because these were completely either in the dimeric or monomeric

state in the range of protein concentration used (ND, not deter-

mined). However, the detection limit of the instrumentation

employed, which may be estimated to be approximately 1% (per-

centage of detectable monomer in a dimeric sample or vice versa),

restricts the K

d

for the dimeric holo-forms to values £8·10

)9

M

)1

and the K

d

for the monomeric double mutant apoenzyme to values

‡5·10

)4

M

)1

(calculated on the basis of Eqn (1), assuming that

1% of undetected dimer or monomer were present in the sedimen-

tation velocity experiments carried out at a subunit concentration of

2.5 lM).

b

Calculated on data collected at 420 nm with an enzyme

sample at a subunit concentration of 33 lM. Data of all other exper-

iments were collected at 277 nm.

c

In the sedimentation velocity

experiments on the L85A apoenzyme, approximately 2% of sub-

units sedimented very slowly in the form of aggregates.

Role of hydrophobic contacts in serine hydroxymethyltransferase R. Florio et al.

134 FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 132–143 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS

ing the dissociation equilibrium (Eqn 1). A complete

shift of the equilibrium in favor of the dimeric form

was obtained when l-serine (1 mm) was added to the

double mutant holoenzyme (Fig. 2).

PLP binding properties

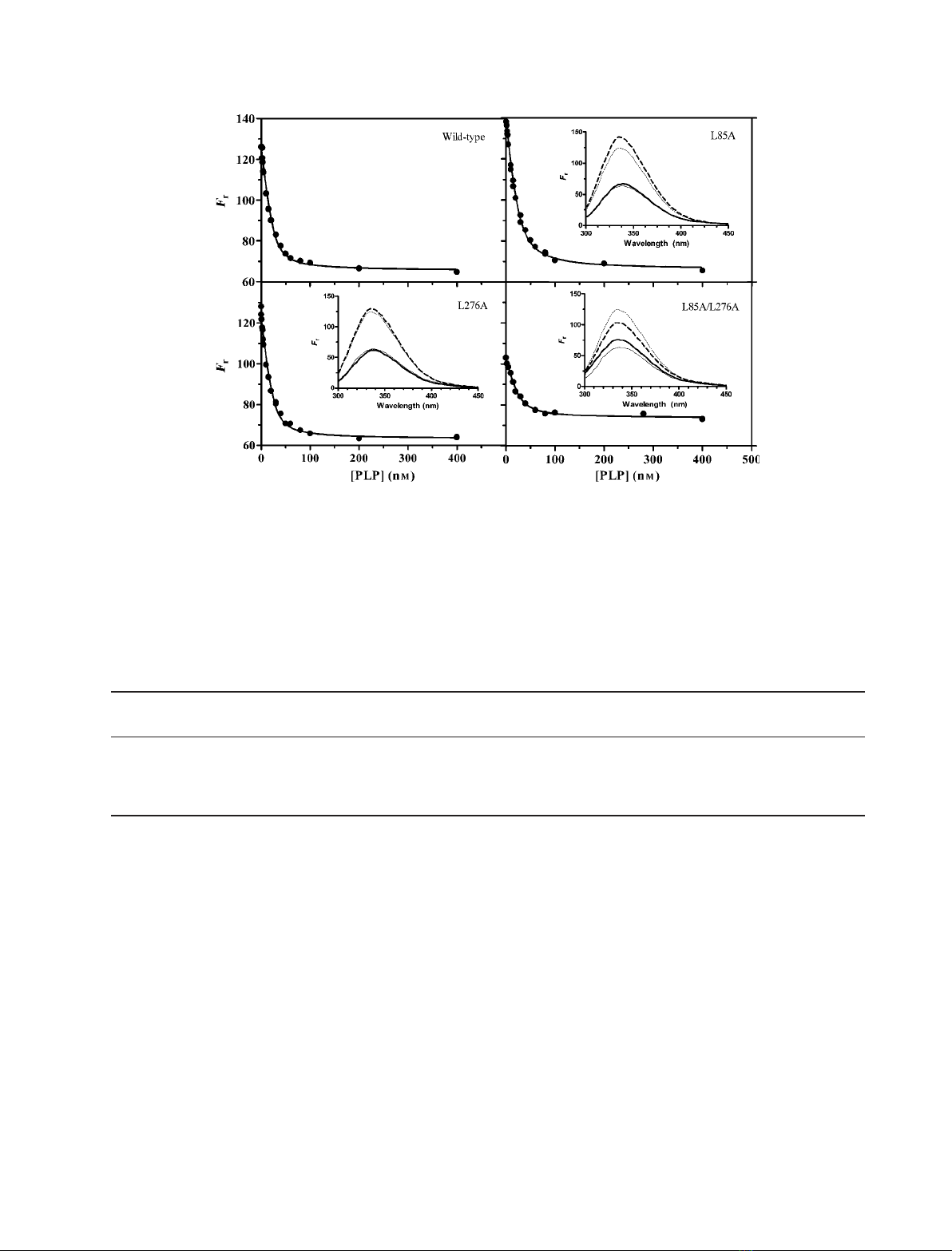

The affinity of wild-type and mutant forms for the

cofactor was measured to evaluate the impact of the

mutations on the structure of the PLP binding site.

Because PLP binding to apo-eSHMT is known to

quench the intrinsic fluorescence emission of the

enzyme [10], without changing the wavelength of maxi-

mum emission, the dissociation constant of the binding

equilibrium was calculated from saturation curves

obtained by measuring the fluorescence emission of

apoenzyme samples (26 nmsubunit concentration) at

increasing PLP concentrations (Fig. 3). Table 2 shows

that the apparent K

d

values calculated from least

square fitting of experimental data points to Eqn (2)

are essentially the same for all enzyme forms. The cal-

culated relative fluorescence intensities in the absence

of PLP (F

0

) or in the presence of saturating concentra-

tions of cofactor (F

inf

) were: F

0

= 125 ± 1 and

F

inf

=65 ± 1 for the wild-type enzyme; F

0

= 139 ± 1

and F

inf

= 66 ± 1 for L85A; F

0

= 122 ± 1 and

F

inf

= 63 ± 1 for L276; and F

0

= 103 ± 1 and

F

inf

= 73 ± 1 for L85A ⁄L276A. The higher fluores-

cence with respect to wild-type observed with the L85A

apoenzyme may be explained by the presence of a small

percentage of subunits present as aggregates (Table 1).

A remarkable difference is noted with respect to the

intrinsic fluorescence emission intensities of apo- and

holo-forms of the L85A ⁄L276A double mutant: the

relative fluorescence emission of the double mutant

apoenzyme is considerably lower than that of the other

apo-forms and PLP binding does not quench fluores-

cence to the same extent it does with the other holo-

forms, although the wavelength of maximum emission

is the same for all enzyme forms (Fig. 3, insets).

In the light of the results obtained from the ultra-

centrifuge experiments, it should be noted that, at a

concentration of 26 nm, the association state of subun-

its is expected to vary among wild-type and mutant

enzymes. Indeed, it may be calculated, using the disso-

ciation constants showed in Table 1 and according to

Eqn (1), that, at this concentration, the apoenzyme

subunits of wild-type eSHMT are mostly in the

dimeric state (for a fraction ‡90%), the apo-L85A is

approximately 75% dimeric, whereas the apo-L276A

and the apo-L85A ⁄L85A mutants are in the mono-

meric state. The association state of the holoenzymes

can be estimated to be ‡90% dimeric for all enzyme

forms, except for the L85A ⁄L276A double mutant,

Fig. 2. Sedimentation velocity distributions obtained with apo- and holo-forms of wild-type and mutant eSHMTs. Sedimentation velocity

measurements were performed at 116 480 gon 2.5 lM(subunit concentration) holoenzyme (—) and apoenzyme (- - -) samples kept at

20 Cin50mMNaHepes buffer (pH 7.2), containing 200 lMdithiothreitol and 100 lMEDTA. L-serine (1 mM) was added to a sample of the

L85A ⁄L276A double mutant holoenzyme (ÆÆÆÆÆ). Absorbance data were all collected at 277 nm, except in the case of a sedimentation experi-

ment carried out on the double mutant holoenzyme at a subunit concentration of 33 lM, when the absorbance of protein-bound cofactor

was measured at 420 nm (Æ-Æ-Æ).

R. Florio et al. Role of hydrophobic contacts in serine hydroxymethyltransferase

FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 132–143 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS 135

which is expected to be mostly in the monomeric state.

Therefore, the similar values of dissociation constant

obtained with wild-type and mutant enzymes suggest

that the cofactor binds to monomeric and dimeric

forms with similar affinities.

Catalytic properties

SHMT catalyses the reversible transfer of the C

b

of

l-serine to tetrahydropteroylglutamate (H

4

PteGlu),

with formation of glycine and 5,10-methylene-H

4

Pte-

Glu. However, in the absence of H

4

PteGlu, it also

accelerates the cleavage of several different l-3-hydr-

oxyamino acids to glycine and the corresponding

aldehyde [11]. Both erithro and threo forms of l-3-

phenylserine are rapidly cleaved to glycine and benzal-

dehyde [12,13]. The serine hydroxymethyltransferase

and l-threo-phenylserine aldolase activities of all

eSHMT forms were assayed using enzyme samples (at

0.05 and 3 lmsubunit concentrations, respectively)

saturated with PLP. The calculated kinetic parameters

of both reactions are shown in Table 2. The L85A

mutation had virtually no effect on the catalytic prop-

erties of the enzyme. Minor differences with respect to

Table 2. Dissociation constants of PLP binding equilibrium and kinetic parameters determined with wild-type and mutant eSHMTs. Para-

meters are expressed as the mean ± SD determined by nonlinear least squares fitting of data to the related equation (see Experimental

procedures).

K

d

PLP

a

(nM)

aK

mb

Ser

(mM)

aK

mb

H

4

PteGlu

(lM)

k

cat

SHMT

c

(min

)1

)

K

m

/-Ser

d

(mM)

k

cat

/-Ser

d

(min

)1

)

Wild-type 5.11 ± 1.14 0.14 ± 0.01 7.03 ± 0.88 686.6 ± 21.7 36.3 ± 1.4 202.1 ± 4.2

L85A 5.88 ± 0.73 0.15 ± 0.01 7.16 ± 1.57 647.4 ± 36.3 37.4 ± 2.9 257.8 ± 13.7

L276A 5.01 ± 0.87 0.20 ± 0.01 4.35 ± 0.52 400.5 ± 10.8 42.6 ± 1.8 132.3 ± 3.2

L85A ⁄L276A 6.50 ± 1.69 0.20 ± 0.01 11.20 ± 1.34 400.0 ± 15.3 42.1 ± 4.5 173.9 ± 10.7

a

Dissociation constant of PLP binding equilibrium.

b

Apparent K

m

of either L-serine or H

4

PteGlu in serine hydroxymethyltransferase reaction

when the other substrate is at saturating concentration.

c

Catalitic constant of the serine hydroxymethyltransferase reaction.

d

Kinetic param-

eters of the L-threo-3-phenylserine cleavage reaction.

Fig. 3. Comparison of PLP-binding saturation curves obtained with wild-type and mutant enzymes. Apoenzyme samples (26 nM) were mixed

with different concentrations of PLP (1–400 nM)in50mMNaHepes (pH 7.2), containing 200 lMdithiothreitol and 100 lMEDTA, at 20 C.

Fluorescence emission spectra were measured in a 1-cm quartz cuvette with excitation at 280 nm. The graphs report the relative fluores-

cence intensity at 336 nm (F

r

) as a function of the total PLP concentration (i.e. the concentration of free and enzyme-bound PLP). The contin-

uous lines are those calculated from the least square fitting of experimental data to Eqn (2). Insets show comparisons between the intrinsic

fluorescence emission spectra of holoenzyme (—) and apoenzyme (- - -) forms of wild-type (thick lines) and mutant (thin lines) eSHMT.

Role of hydrophobic contacts in serine hydroxymethyltransferase R. Florio et al.

136 FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 132–143 ª2008 The Authors Journal compilation ª2008 FEBS