Stepwise adaptations of citrate synthase to survival at

life’s extremes

From psychrophile to hyperthermophile

Graeme S. Bell

1

, Rupert J. M. Russell

2

, Helen Connaris

2

, David W. Hough

1

, Michael J. Danson

1

and Garry L. Taylor

1,2

1

Centre for Extremophile Research, Department of Biology and Biochemistry, University of Bath, UK;

2

Centre for Biomolecular

Sciences, University of St Andrews, St. Andrews, UK

The crystal structure of citrate synthase from the thermo-

philic Archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus (optimum growth

temperature ¼85 C) has been determined, extending the

number of crystal structures of citrate synthase from differ-

ent organisms to a total of five that span the temperature

range over which life exists (from psychrophile to hyper-

thermophile). Detailed structural analysis has revealed

possible molecular mechanisms that determine the different

stabilities of the five proteins. The key to these mechanisms is

the precise structural location of the additional interactions.

As one ascends the temperature ladder, the subunit interface

of this dimeric enzyme and loop regions are reinforced by

complex electrostatic interactions, and there is a reduced

exposure of hydrophobic surface. These observations reveal

a progressive pattern of stabilization through multiple

additional interactions at solvent exposed, loop and inter-

facial regions.

Keywords: citrate synthase; Sulfolobus; citrate synthase;

thermostability; crystal structure; ion networks.

Comparative structural analysis of the same protein isolated

from mesophiles and thermophiles have highlighted many

structural adaptations that confer protein thermostability

[1–6]. The importance of electrostatic interactions at specific

locations within the structure, and particularly the presence

of ion-pair networks, is a feature that is common to almost

all the hyperthermophilic proteins [7–10], although many

other additional differences such as improved hydrophobic

packing, compactness and additional hydrogen bonds have

been observed in other proteins.

For our analysis we have chosen the enzyme citrate

synthase (CS) (EC 4.1.3.7), which catalyses the condensa-

tion of oxaloacetate and acetyl-CoA to form citrate and

CoA. The enzyme from psychrophilic, mesophilic and

thermophilic sources has been intensively studied both

kinetically [11–13] and structurally [3,14]. Crystal structures

exist for CS from a psychrophilic Antarctic bacterium

Arthrobacter strain DS2-3R (growth optimum ¼31 C)

[15], pig (37 C) [16], and the Archaea Thermoplasma

acidophilum (55 C) [17] and Pyrococcus furiosus (100 C)

[18]. To extend our previous studies we have chosen the

organism Sulfolobus solfataricus, a thermophilic Archaeon

that optimally grows at 85 C. The gene for Sulfolobus

solfataricus CS has been cloned and sequenced [19], and

over-expressed in E. coli. The purified recombinant protein

exists as a homodimer of M

r

¼81,000, with each monomer

comprising 379 amino acids. The following abbreviations

will be used for the CSs, including their optimal growth

temperatures: Arthrobacter: ArCS(31), pig: PigCS(37),

T. acidolphilum: TpCS(55), S. solfataricus:ScCS(85),and

P. furiosus: PfCS(100).

The structure of unliganded SsCS(85) reported in this

paper can now be entered into the temperature ladder of CS

structures, and fills in the gap between the 55 C and 100 C

enzymes. Six CS crystal structures from five host organisms

(Table 1) can now be used for comparative analysis in order

to identify some of the structural features that could confer

(hyper)thermostability in this enzyme family.Ascanbe

seen from Table 1, the organisms span the range of

temperatures at which life is known to exist, and the

inherent stability of each CS, from in vitro measured half-

lives of thermal inactivation [19–21], increases with the

optimum growth temperature of the host cells. The structure

of the SsCS(85) is thus discussed in comparison with the

other CS structures, and trends in structural changes are

correlated with the increasing thermal stabilities across the

homologous series of enzymes. In terms of thermostability,

the enzymes fall into two broad classes based on the

temperature at which the half-life equals 8 min: the psychro-

phile and pig enzymes at the lower end with temperatures of

45 Cand58 C, and the archaeal enzymes at the upper end

with temperatures of 87 C, 95 Cand100C.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Crystallization and structure solution

Recombinant SsCS(85) was purified as described previously

[19]. Crystallization trials were carried out using the

hanging-drop vapour diffusion method using the Hampton

Research Screens. A single rod-like crystal of approximate

dimensions 2 ·0.1 ·0.1 mm grew in a 6-lL drop contain-

ing 2 lLSsCS(85) (10 mgÆmL

)1

)with10m

M

citrate and

Correspondence to G. Taylor, Centre for Biomolecular Sciences,

University of St. Andrews, St. Andrews, KY16 9ST, UK.

E-mail: glt2@st-and.ac.uk

(Received 3 July 2002, revised 8 October 2002,

accepted 4 November 2002)

Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 6250–6260 (2002) FEBS 2002 doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03344.x

CoA, 2 lLof100m

M

Tris/HCl, pH 7.2, containing 17%

(v/v) PEG 8K, and 2 lLof0.1

M

CaCl

2

.Thecrystalgrewin

a partially dried out drop after six months. X-ray data were

collected at room temperature on a 30-cm Mar image plate

detector. Diffraction extended to 2.7 A

˚resolution. The

crystal was translated stepwise perpendicular to the beam to

maximize the completeness of the data and to overcome

radiation damage of the crystal. The data were reduced and

scaled using

DENZO

/

SCALEPACK

[22] (Table 2). The asym-

metric unit of the P2

1

unit cell contains two dimers with a

solvent content of 51%. The structure of SsCS(85) was

solved by molecular replacement using the program

AMORE

[23]. Because the crystallization solutions contained both

citrate and CoA, it was assumed that the closed form of

SsCS(85) had crystallized; therefore, initial attempts were

made to solve the structure using the closed structures of

Pf CS(100) or ArCS(31) as the search model, but this did not

produce any clear solutions. Attempts were subsequently

made using the open structure of the TaCS(55) dimer as the

search model. Using data in the resolution range of 15–6 A

˚

and a Patterson integration radius of 25 A

˚, 50 solutions

from the rotation function were calculated. Using the same

resolution range for the translation search, the top solution

(33rd highest from the rotation search) had a correlation

coefficient (CC) of 32.0 and R-factor of 53.4% (compared

with the next highest peak with a background CC of 23 and

R-factor of 56%). This solution was fixed, and a solution

for the second dimer in the asymmetric unit was identified

(CC of 37.7% and R-factor of 51.9%, compared to the next

highest peak of 31 and 53%, respectively). After a rigid-

body refinement in

AMORE

of the two dimers, the final

solutions had a CC of 56.6 and R-factor of 41.3%. The

failure to find a solution using the closed form of the

homologous enzyme, but a clear solution with the open

forms, strongly suggested that the SsCS(85) had unexpect-

edly crystallised in the open, unliganded form.

Refinement and validation

The restrained refinement of SsCS(85) was performed using

REFMAC

[24]. The initial R-factor in

REFMAC

(after rigid

body refinement) was 48.3% (R

free

¼48.6%) and final

R-factor of 20.8% (R

free

¼28.5%) for all data from 20.0 A

˚

to 2.7 A

˚

1,2 . Tight non crystallographic symmetry (NCS)

restraints for both main-chain and side-chain were used

initially and six cycles of refinement carried after which the

R-factor was 36.3% (R

free

¼40.5%). Keeping the tight

NCS restraints, individual isotropic B-factor refinement was

then carried out, bringing the R-factor down to 24.7% (R

free

31.2%), after which the NCS restraints were gradually

loosened and the four monomers were built independently.

NCS restraints were controlled in

PROTIN

and, during the

refinement procedure, side-chain followed by main-chain

restraints were gradually loosened, with a final round

removing the NCS restraints continuing to lower the R

free

value.

The first two residues at the N-terminus and last seven

residues of the C-terminal arm were not seen in the poorly

defined electron density of these parts of the structure in all

four monomers. One conflict with the sequence data was

residue 57, which had been assigned as arginine and was

found from analysis of the electron density map to be a

proline (this is a totally conserved proline in all the other

known CSs). The position of the small domain with respect

to the large domain in SsCS(85) is the same as previously

observed in TaCS(55) [17]; this together with the absence of

density for substrates in the active site, supports the previous

speculation that the structure is the openform of the

enzyme. After 24 rounds of refinement in

REFMAC

, the final

R-factor was 20.8% (R

free

¼28.5%) (Table 2). The quality

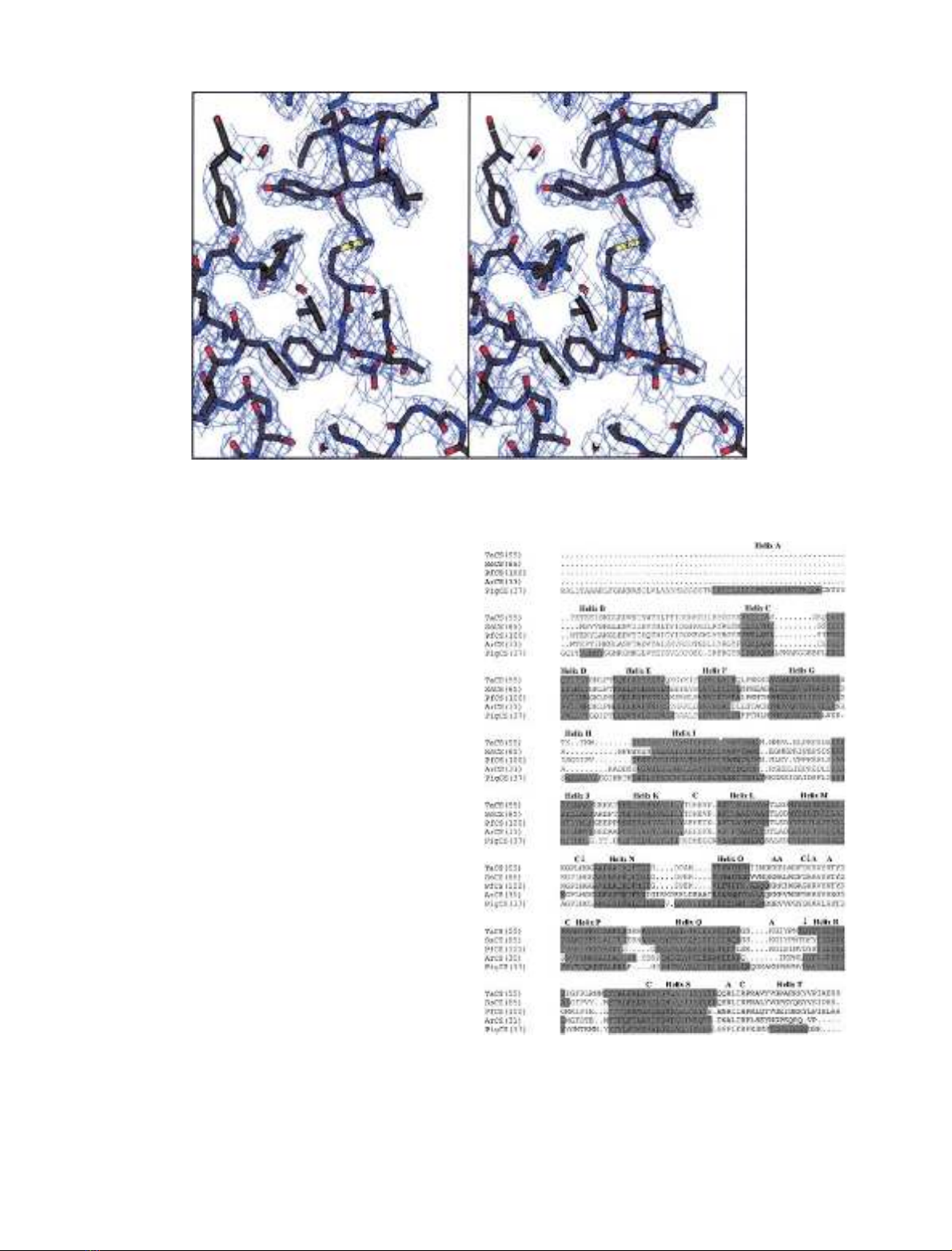

ofthefinalelectrondensityisshowninFig.1.

Table 2. Table displaying native data collected and refinement statistics

for the SsCS. Data in parentheses correspond to the high resolution

data shell (2.82–2.71 A

˚).

Space group P2

1

Unit cell dimensions a ¼77.3 A

˚,b¼97.9 A

˚,

c¼119.3 A

˚,b¼107.6

Resolution limit 2.7 A

˚

Data completeness 88.6% (91.2%)

R

merge

7.2% (22.9%)

I/rI 9.37 (3.25)

Total No. of reflections 148169

Unique reflections 46758

R-factor 20.8%

Free R-factor 28.5%

No. protein atoms 11 742

Rmsd bond lengths (A

˚) 0.009

Rmsd bond angles () 0.032

Table 1. CS structures used for analysis.

Source

organism

Optimum growth

temperature

(C)

CS

Temperature (C) at which

the half-life equals 8 min

Substrates in

crystal structure

Data resolution

(A

˚)

Arthrobacter DS23R 31

a

45 Citrate and CoA 2.1

Pig 37 58 Citrate only

Citrate and CoA

2.7

2.0

Thermoplasma acidophilum 55 87 – 2.5

Sulfolobus solfataricus 85 95 – 2.7

Pyrococcus furiosus 100 100 Citrate & CoA 1.9

a

It should be noted that, although Arthrobacter DS23R was isolated from a habitat temperature of approximately 0 C, this organism

displays a relatively high optimum growth temperature; therefore, although it is described here as psychrophilic, it should perhaps more

correctly be referred to as psychrotolerant.

FEBS 2002 Citrate synthase from psychrophile to hyperthermophile (Eur. J. Biochem. 269) 6251

The Ramachandran plot shows that for the four mono-

mers in the asymmetric unit, 91.3% of residues lie in the

most favoured regions, with only 8.7% in the allowed

regions and no residues appearing in the generously allowed

or disallowed regions (excluding glycine and proline

residues). Atomic coordinates have been deposited in the

Protein Databank with accession code 107x

3.

RESULTS

Overall structural comparisons

All the eukaryotic

4, archaeal and Gram-positive bacteria CSs

are homo-dimeric structures with each monomer consisting

of a large and small domain. In addition, they are almost

entirely a-helical; the pigCS contains 20 a-helices (A-T) with

theenzymefromArCS(31), TaCS(55), SsCS(85) and

PfCS(100) containing 16 a-helices, all of which have an

equivalent in pigCS (helices A, B, H, and T are not present)

(Figs 2 and 3). Of the 16 equivalent helices, the large domain

comprises 11 helices (C-M and S) and the small domain five

helices (N-R). The small domain has been classed as

residues 217–321 inclusive for SsCS(85).

The active sites of CSs comprise residues from both

monomers and therefore CS is only active as a dimer,

stressing the importance of maintaining dimeric integrity as a

prerequisite for activity. Binding of citrate and CoA to the

active site has been discussed in detail for PfCS(100) and

ArCS(31), and the differences with respect to the pig enzyme

noted [15,18]. The SsCS(85) structure has no substrate

bound, but the location of active site residues can be

identified by comparison with the liganded PfCS(100)

structure. The citrate-binding residues comprising three

arginine residues, R267 (helix P), R338 (helix S) and R358¢

(where the prime denotes the residue of the second mono-

mer), and three histidine residues, H183 (loop K-L), H218

(loop M-N) and H258 (loop O-P), are equivalent to those

found in PfCS(100). The binding residues for the three

Fig. 2. Structurally based sequence alignment of the five CSs discussed.

Helices A to T are shaded, and the location of the small domain is

indicated by lowercase sequence letters. The three catalytic residues are

indicated by fl. The three arginines and histidines involved in binding

citrate are marked with a C. The residues involved in binding the three

phosphates of CoA are marked with an A. The sequence numbering is

shownatthestartofeachline.

Fig. 1. Stereo-diagram showing a typical region of the final 2Fo-Fc electron density map contoured at 1 r.

6252 G. S. Bell et al. (Eur. J. Biochem. 269)FEBS 2002

phosphate groups of CoA are likely to be K250 (loop O-P)

and K306 (loop Q-R), R259 and K262 (both loop O-P), with

the third phosphate being co-ordinated by R355¢from the

second monomer. The catalytic residues H218, H258 and

D313 (loop Q-R) are also present in SsCS(85) and are in

a similar position to the PfCS(100) residues. It is likely

therefore that SsCS(85) binds substrates in a similar man-

ner to PfCS(100) and that the mechanism of catalysis is the

same.

The dimer interface of all the CSs is made up of two parts

and comprises residues solely in the large domain; the main

part is the eight a-helical sandwich of four antiparallel pairs

of helices (F, G, M and L), with the second being the

additional interaction of N- and C-terminal regions (Fig. 3).

The pigCS is different from the other four CSs in terms of

the topology of the C-terminal region. In the other four, the

C-terminal arm of one monomer wraps around the other

monomer, clasping the two together [18], and results in

more extensive interactions, including those with the

N-terminus. It is important to note that as the C-terminal

arms of the TaCS(55) and SsCS(85) are not complete in the

structures (see below), there may be additional interactions

present that have not been observed. This also suggests that

the C-terminal arm seems to be ordered only in the presence

of substrates.

Sequence and structural statistics

Pairwise sequence alignments were carried out using the

program

BESTFIT

from the Wisconsin

GCG

sequence analysis

package, and superposition was carried out using the least

squares fit in

O

[25] for fitting of alpha-carbon atoms

(starting from three conserved atoms). These statistics are

listed in Table 3.

Sequence identities between the various CSs for which

3D-structures have been determined range from 20%

[eukaryotic

5vs. bacterial or archaeal) to 60% (SsCS(85)

and TaCS(55)]. These identities are reflected in the root

mean square (RMS) deviations between the alpha-carbons

of the structures, with the most similar structures being the

TaCS(55) and SsCS(85), and with the PfCS(100) and

ArCS(31) pair also showing a very low RMS deviation. As

some structures are in the open conformation and some

have substrates bound, the large and small domains of each

enzyme were compared separately (Table 3); in general,

such an analysis shows the same trend as that for the whole

dimer but the small domains tend to be more highly

conserved. As is suggested later, this may correlate with

differences particularly relating to the dimer interface, to

which the small domain does not contribute, and may reflect

the fact that the majority of the substrate-binding and

catalytic residues are from the small domain.

The molecular mechanisms underlying protein thermal

stability

In our comparison of CS atomic structures from organisms

spanning a wide-range of growth temperatures, the deter-

mination of the SsCS(85) structure fills an important gap

between the enzyme from Thermoplasma (55 C) and

Pyrococcus (100 C). With the structure reported in this

paper, we can now look for trends in the structures that

might correlate with the increasing thermostabilities of these

enzymes. However, the complex nature of the stabilization

of a protein structure lends itself to many types of

comparative analysis, and the results presented below are

those where significant differences exist between the struc-

tures. Other types of analysis (e.g. of hydrogen bonds and

helix capping) have been performed but are not included

Fig. 3. Schematic drawings of CS. Fromtoptobottom:ArCS(31),

PigCS(37), TaCS(55), SsCS(85) and PfCS(100). The right hand col-

umn represent views obtained by rotating the images in the left hand

column by 90about a horizontal axis. N- and C-terminii are denoted

by blue and red spheres, respectively. The small domains (helices N to

R) are coloured in a lighted shade. Catalytic residues, and citrate and

Co-A where appropriate, are shown in ball-and-stick representation.

All figures were created using

BOBSCRIPT

[51] and

GL

_

RENDER

(L. Esser

and J. Deisenhofer, unpublished results).

FEBS 2002 Citrate synthase from psychrophile to hyperthermophile (Eur. J. Biochem. 269) 6253

due to there being no significant differences between the

different structures.

Compactness and surface characteristics

The accessible surface area was calculated using the program

GRASP

[26] and the volume and cavity detection were

determined using the program

VOIDOO

[27] with a probe

radius 1.4 A

˚and grid spacing of 0.75 A

˚. All calculations for

closed structures were carried out in the absence of substrate,

and the results are summarized in Table 4.

ArCS(31), TaCS(55) and PfCS(100) have very similar

surface areas, with that of SsCS(85) being slightly higher;

however, all four enzymes have a considerably smaller

surface area and volume than the pigCS(37), even when

deleting the first 35 residues from the pig enzyme (these 35

amino acids comprise helices A and B, which are absent in

the other CSs being considered). A similar pattern to the

total accessible surface area (ASA)

6is found when compar-

ing the overall volume, with pigCS(37) having a consider-

ably larger volume than the other CSs (again, even when

calculated with the N-terminally deleted structure).

However, it is also notable that the smallest volume is

exhibited by the psychrophilic CS (8.36 ·10

4

A

˚

3

). All the

CSs have a similar percentage of atoms buried, although the

hyperthermophilic Pf CS(100) exhibits the highest with

54.5%.

Examination of the exposed hydrophobic area shows a

more obvious trend. Despite all the archaeal and bacterial

CSs having a similar overall ASA, there is quite a difference

in hydrophobic exposure when comparing ArCS(31) with

the other CSs; the closed conformation of the ArCS(31) has

7854 A

˚

2

overall exposed hydrophobic area (representing

29% of the total ASA) compared with the closed PfCS(100)

with only 4942 A

˚

2

(18% of total ASA). Thus, on average,

ArCS(31) exposes 23 A

˚

2

per hydrophobic residue compared

with 16 A

˚

2

per hydrophobic residue in PfCS(100). The

total amount (A

˚

2

) of hydrophobic surface area shows a

decrease as the thermostability of the protein increases, a

trend observed in other structural comparisons [4]. SsCS(85)

also follows the trend observed in PfCS(100), with the

elimination of all cavities capable of accommodating a

solvent molecule, indicating that this is a prerequisite for

maintaining integrity at high temperatures. The number of

internal cavities (and their total volumes in A

˚

2

calculated by

VOIDOO

) are 1 (104), 6 (476), 3 (218), 3 (184), 0 (0) and 0 (0)

Table 3. Overall comparison of primary and 3D structures of CSs. In the top half of the table the RMS deviations between Caatoms (in A

˚)aregiven

for complete dimers, the large domain and the small domain, with the number of contributing pairs of Caatoms in parantheses. In the bottom half

of the table, the percentage sequence identities and similarities are shown, the latter in parentheses.

Enzyme

(open)

ArCS(31)

(closed) PigCS(37) PigCS(37) TaCS(55) SsCS(85) PfCS(100)

ArCS(31) – 2.27 (560) 2.12 (630) 1.97 (604) 1.94 (610) 1.32 (719)

1.74 (242) 1.53 (252) 1.57 (259) 1.07 (262)

1.79 (96) 1.59 (90) 1.51 (90) 1.27 (92)

PigCS(37) (open) – – 1.19 (730) 1.95 (651) 1.88 (646) 2.15 (550)

2.16 (533) 2.08 (519) 2.04 (631)

PigCS(37) (closed) 27% (50%) – – 1.81 (233) 1.79 (232) 1.84 (245)

1.60 (82) 1.55 (82) 1.49 (90)

0.87 (719) 2.03 (581)

TaCS(55) 32% (54%) – 22% (48%) – 0.76 (256) 1.66 (247)

0.76 (104) 1.02 (95)

SsCS(85) 34% (55%) – 27% (50%) 59% (76%) – 1.94 (597)

1.53 (245)

1.03 (96)

PfCS(100) 40% (58%) – 31% (53%) 42% (62%) 46% (67%) –

Table 4. Accessible surface area (ASA) and volume statistics of CSs.

CS

ArCS(31)

(closed)

PigCS(37)

(open)

PigCS(37)

(closed)

PigCS(37)

(closed,

N-terminally

deleted)

TaCS(55)

(open)

SsCS(85)

(open)

PfCS(100)

(closed)

ASA ( ·10

4

A

˚

2

) 2.72 3.34 3.20 2.99 2.72 2.82 2.72

No. of atoms calculated for 5784 6888 6884 6344 5722 5879 5961

No. of atoms buried 3044 3469 3601 3307 2955 3014 3248

Atoms buried (%) 52.6 50.4 52.3 52.1 51.6 51.3 54.5

Volume ( ·10

4

A

˚

3

) 8.36 9.96 9.98 9.18 8.71 8.51 8.65

Total area hydrophobic exposed (A

˚

2

) 7854 6654 6246 – 6001 5513 4942

% Hydrophobic of total ASA 29 20 20 – 22 20 18

6254 G. S. Bell et al. (Eur. J. Biochem. 269)FEBS 2002