RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access

Treatment of alcohol dependence with low-dose

topiramate: an open-label controlled study

Thomas Paparrigopoulos

1*

, Elias Tzavellas

1†

, Dimitris Karaiskos

1†

, Georgia Kourlaba

2†

, Ioannis Liappas

1†

Abstract

Background: GABAergic anticonvulsants have been recommended for the treatment of alcohol dependence and

the prevention of relapse. Several studies have demonstrated topiramate’s efficacy in improving drinking behaviour

and maintaining abstinence. The objective of the present open-label controlled study was to assess efficacy and

tolerability of low-dose topiramate as adjunctive treatment in alcohol dependence during the immediate post-

detoxification period and during a 16-week follow-up period after alcohol withdrawal.

Methods: Following a 7-10 day inpatient alcohol detoxification protocol, 90 patients were assigned to receive

either topiramate (up to 75 mg per day) in addition to psychotherapeutic treatment (n = 30) or psychotherapy

alone (n = 60). Symptoms of depression and anxiety, as well as craving, were monitored for 4-6 weeks immediately

following detoxification on an inpatient basis. Thereafter, both groups were followed as outpatients at a weekly

basis for another 4 months in order to monitor their course and abstinence from alcohol.

Results: A marked improvement in depressive (p < 0.01), anxiety (p < 0.01), and obsessive-compulsive drinking

symptoms (p < 0.01) was observed over the consecutive assessments in both study groups. However, individuals

on topiramate fared better than controls (p < 0.01) during inpatient treatment. Moreover, during the 4-month

follow up period, relapse rate was lower among patients who received topiramate (66.7%) compared to those who

received no adjunctive treatment (85.5%), (p = 0.043). Time to relapse in the topiramate augmentation group was

significantly longer compared to the control group (log rank test, p = 0.008). Thus, median duration of abstinence

was 4 weeks for the non-medicated group whereas it reached 10 weeks for the topiramate group. No serious side

effects of topiramate were recorded throughout the study.

Conclusions: Low-dose topiramate as an adjunct to psychotherapeutic treatment is well tolerated and effective in

reducing alcohol craving, as well as symptoms of depression and anxiety, present during the early phase of alcohol

withdrawal. Furthermore, topiramate considerably helps to abstain from drinking during the first 16-week post-

detoxification period.

Background

Alcohol dependence is a multifactorial disorder influ-

enced by interacting genetic, biological, psychological

and environmental factors. Pharmacologically, alcohol

is considered to be a potent central nervous system

depressant and its action is mediated through multiple

neurotransmitter systems, including the GABAergic, glu-

tamatergic, dopaminergic serotoninergic, and opiatergic

system. This complex neurobiological network, which is

involved in the regulation of alcohol preference, intake,

and the rewarding and craving components of alcohol

dependence, has been the target of various pharmacolo-

gical agents, albeit with only limited success. In this

context, there has been a growing interest in the use of

anticonvulsant medications in the field because these

agents may act on the neurobiological substrate of

addiction [1,2]. In this vein, the anticonvulsant topira-

mate has been suggested to be promising for treating

alcohol dependence [3,4]. Although the mechanism is

unclear, modulation of the dopamine reward pathways

of the brain through antagonizing excitatory glutamate

receptors at a-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-

propionic acid and kainate receptors and inhibiting

* Correspondence: tpaparrig@med.uoa.gr

†Contributed equally

1

Athens University Medical School, 1st Department of Psychiatry, Eginition

Hospital, Athens, Greece

Full list of author information is available at the end of the article

Paparrigopoulos et al.BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11:41

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/11/41

© 2011 Paparrigopoulos et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative

Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

dopamine release [5,6] within the mesocorticolimbic sys-

tem while enhancing inhibitory GABA (by binding to a

site of the GABA-A receptor) [7], has been proposed as

being responsible for its effectiveness [8]. This dual

action of topiramate is supposed first to lead to a dopa-

mine decrease in the nucleus accumbens in response to

alcohol ingestion, and consequently to a reduction of its

rewarding/reinforcing potential, and second to minimize

withdrawal symptoms by moderating the effect of

chronic alcohol consumption on neural system excitabil-

ity. Thus, targeting at both facets of addiction, i.e., crav-

ing and feelings of inner tension and discomfort, relapse

may be less likely. However, several issues regarding

dosing, duration and tolerability of treatment with topir-

amate have not been adequately addressed as yet.

Treatment of alcohol dependence is a two-phase pro-

cess, which aims at alcohol withdrawal and subsequent

long-term abstinence and relapse prevention [9]. Depend-

ing on the phase, different priorities may be set. Thus,

pharmacotherapy during and immediately after detoxifica-

tion may protect from withdrawal dysphoric symptoms

and can reduce anxiety and symptoms of depression

[10-12]. Thereafter, medication can be used to reduce

craving and reward from alcohol use. GABAergic and

glutamatergic medications might be promising candidates

for helping during both phases of alcohol dependence

treatment [13].

The objective of the present open-label controlled study

was to assess the efficacy and tolerability profile of low-

dose topiramate as adjunctive treatment in alcohol depen-

dence during the immediate post-detoxification period

and during a 16-week follow-up period after alcohol with-

drawal. The choice of low-dose topiramate was made

based on the existing, albeit limited, literature, which sug-

gests that even low doses of this medication can be benefi-

cial in preventing alcohol relapse [14,15,4]; moreover, a

less aggressive approach with milder side-effects could be

advantageous in terms of treatment adherence. A control

non-medicated group of alcohol-dependent individuals

was used for comparisons in terms of anxiety and depres-

sive symptoms, craving and drinking outcome.

Methods

Study design - participants

The study was an open-label controlled clinical trial. Par-

ticipants were assigned either to a standard alcohol

detoxification group (see below) or to a topiramate aug-

mentation group. Assignment to the topiramate augmen-

tation group was made on a 2:1 ratio; thus, every third

intake was assigned to the topiramate group. In total, 90

alcohol-dependent individuals who consecutively con-

tacted the Drug and Alcohol Addiction Clinic of the

Athens University Psychiatric Clinic at the Eginition

Hospital in Athens, Greece, were enrolled in the study.

Patients had to fulfil the DSM-IV-TR [16] diagnostic cri-

teria for alcohol abuse/dependence and were admitted

for inpatient alcohol detoxification. Informed consent

was obtained from the participants after providing

detailed information on the objectives of the study and

the research/therapeutic protocol. All procedures were

approved by the ethical committee of our institution.

(“Committee on Medical Ethics of the Eginition Hospital”

& Reference No: 1178).

The inclusion criteria were: a) age 18-65 years,

b) absence of a serious physical illness (as assessed

through physical examination and routine laboratory

screening), c) absence of another pre- or co-existing

major psychiatric disorder on the DSM-IV-TR axis I,

d) absence of another drug abuse, and e) participants

with affective or anxiety symptoms were not excluded

from the study if concurrent with an alcohol-abusing

period; individuals who fulfilled a DSM-IV-TR diagnosis

of depressive or anxiety disorder (assessed through the

Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry

[SCAN] [17] and information obtained from a close

relative) were excluded from the study if relevant cri-

teria were met prior to the onset of alcoholism or dur-

ing periods of abstinence.

Participants were assigned to two study groups: the

control group (n = 60), which included subjects treated

with a standard alcohol detoxification protocol, and

the topiramate augmentation group (n = 30), which

included patients who were additionally given topira-

mate (up to 75 mg/day in 2 divided doses). Topiramate

was initiated at a daily dose of 25 mg, before stopping

the last dose of 5 mg diazepam, and was gradually

increased up to 75 mg/day over three weeks (mean

dose: 55.0 ± 19.03 mg/day).

The standard alcohol detoxification protocol was

initiated and completed one week (7-10 days) after

admission to the ward. This protocol includes vitamin

replacement (vitamins C, E and B complex) and oral

administration of diazepam (30-60 mg in divided doses),

with gradual taper off over a week. Thereafter, both

groups were given a standard treatment program with

cognitive-behavioural short-term psychotherapy of 4-

6 week duration (i.e. during their inpatient treatment).

After discharge, patients were assessed at a weekly basis

for 4 more months in order to monitor their course and

abstinence from alcohol. Assessment of abstinence from

alcohol was based on self reports, but it was further

cross-checked with a family member to ascertain accu-

racy of information. Also, serum g-glutamyl transpepti-

dase (g-GT) and an alcohol breath test at each visit were

used to control abstinence. No discrepancies were

observed between these measures of abstinence through-

out the study. Although there is ongoing debate regard-

ing the reliability of self-reports of alcohol consumption,

Paparrigopoulos et al.BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11:41

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/11/41

Page 2 of 7

it has been shown that data thus collected are a valid

source of information in the case of dependent indivi-

duals [18]. Furthermore, g-GT is considered to be a reli-

able marker of alcohol relapse detection [19].

From the total sample (n = 90), eighty-five subjects

(n = 85) were included in the final statistical analysis

because five participants from the control group had

occasionally used benzodiazepines during the follow-up

period on their own initiative, and this was considered

as protocol violation.

Measures

Participants were diagnosed by the Schedules for Clinical

Assessment in Neuropsychiatry [SCAN] and assessed

through the Composite International Diagnostic Interview

[20] (CIDI; section on alcohol consumption) for their pat-

tern of alcohol abuse, potential major life problems related

to alcohol consumption and the occurrence of withdrawal

symptoms in the past. All data pertaining to alcohol use

were self-reported but in order to ascertain accuracy of

information a relative was also interviewed to corroborate

current status and psychiatric history. Furthermore, socio-

demographic data (age, socioeconomic status, marital sta-

tus, level of education) and previous psychiatric history

(pre-existent diagnosis, medication, number of hospitaliza-

tions) were recorded. Symptoms of depression and anxiety

were assessed with the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale

(HDRS) [21] and the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale

(HARS) [22]. Obsessive thoughts about alcohol use and

compulsive behaviours toward drinking (facets of craving)

were estimated with the Obsessive Compulsive Drinking

Scale (OCDS) [23]. Overall functioning was assessed using

the Global Assessment Scale (GAS) [24]. The severity of

withdrawal symptoms was evaluated twice daily during the

first week of alcohol withdrawal with a modified version of

the Addiction Research Foundation Clinical Institute

Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol (CIWA-Ar) [25].

Adverse effects of treatment in both groups were moni-

tored through an adapted version of the Systematic

Assessment for Treatment Emergent Events (COMBINE

SAFTEE) scale, which is a structured instrument for col-

lecting adverse events adapted for clinical studies in the

alcoholism field [26]. Assessments were done at three time

points; initially within 48 h upon entering the program

(time point 0) and subsequently at 21 ± 2 day intervals

(time point 1 & 2) over the 4-6 week study period.

Statistical analysis

The number of subjects that entered into the final analysis

was eighty-five (n = 85). Independent samples t-tests were

used to evaluate differences between groups in terms of

symptoms of depression, anxiety, global functioning and

obsessive-compulsive drinking scores at the different time

points. Within groups differences were estimated with

repeated measures analysis of variance (RMANOVA). For

all reported values the means (± SD) were calculated. Chi-

square statistics were used to compare categorical vari-

ables, as appropriate. Cox proportional hazards model was

used to estimate the hazard ratio (HR) of achieving 16

weeks of continuous abstinence and the Kaplan-Meier

method was applied to calculate the cumulative probability

function of reaching 16 weeks of abstinence for the topira-

mate and the control group. The log-rank test was used to

compare the cumulative probability functions. The pro-

portional hazard assumption of Cox model was assessed

through the appropriate graph. All tests were two-tailed

with statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Data analysis

was performed using the SPSS statistical software package

(SPSS Inc. Chicago, IL, USA).

Results

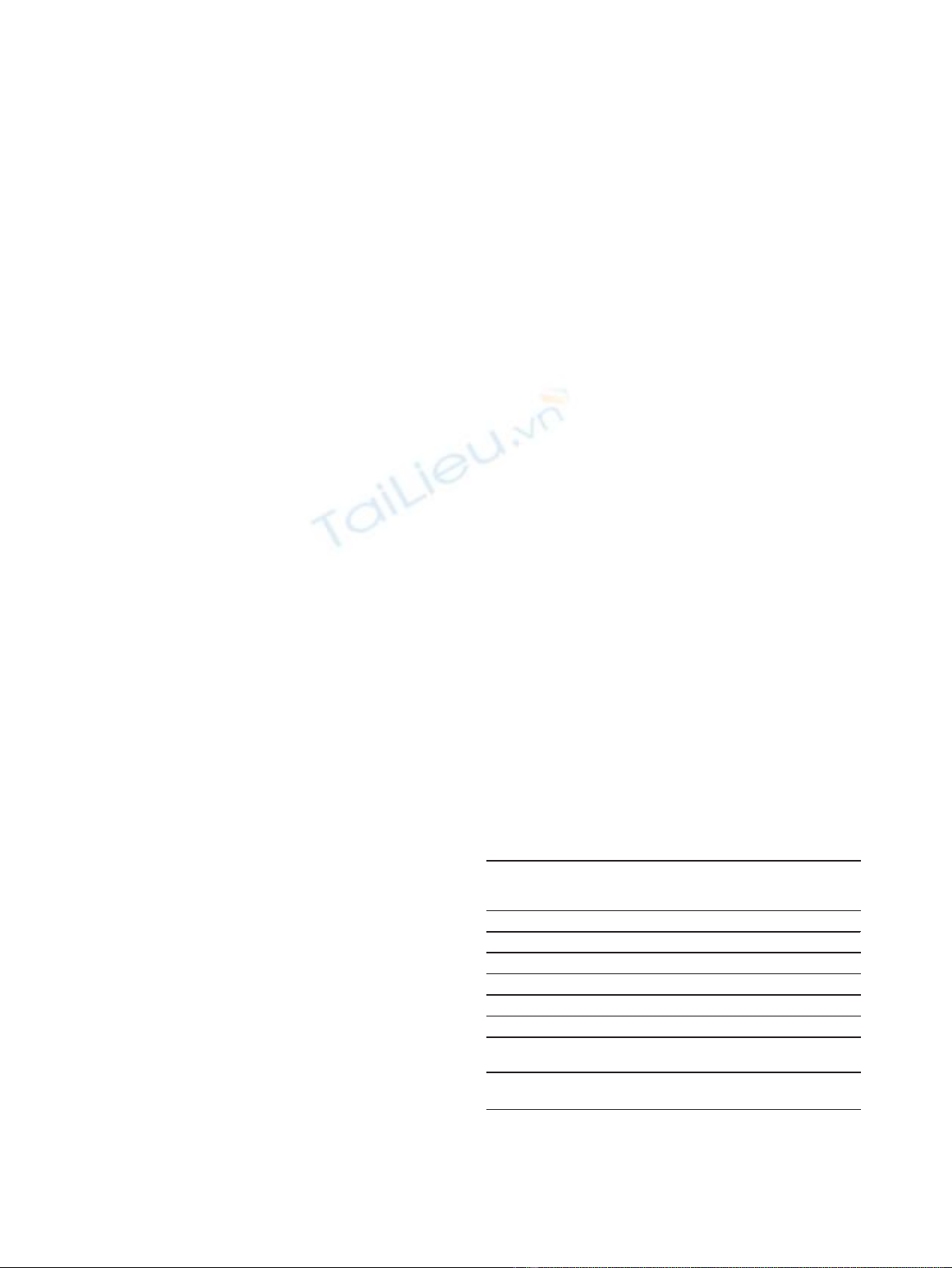

No significant differences were observed between the

control and topiramate group in terms of their sociode-

mographic characteristics, as well as the variables related

to alcohol abuse history and withdrawal symptoms dur-

ing the first week of abstinence (Table 1). As regards

psychopathological symptoms both groups had similarly

high scores on the HDRS, HARS and OCDS, and low

GAS scores upon admission (time 0), which represent a

serious psychosocial impairment. A marked improve-

ment on all these measures was observed in the two

subsequent assessments (time 1 & time 2) in both study

groups [depression (p < 0.01), anxiety (p < 0.01), and

obsessive-compulsive drinking symptoms (p < 0.01)].

However, subjects on topiramate did significantly better

than controls concerning mood improvement, i.e., anxi-

ety and depression (p < 0.05), and craving as well (p <

0.01) (Table 2).

Table 1 Sociodemographic characteristics and variables

related to alcohol consumption of the sample (N = 85)

Topiramate

group

(N = 30)

Control group*

(N = 55)

Mean age, years (± SD) 43.8 ± 8.1 46.3 ± 11.0

Sex (M, F) M: 27, F: 3 M: 48, F: 7

Family status (S, M, D) S: 8, M: 16, D: 6 S: 10, M: 33, D: 12

Socioeconomic status (H, M, L) H: 1, M: 25, L: 4 H: 2, M: 39, L: 14

Educational years 7.6 ± 3.1 8.3 ± 3.8

Age at onset, years (± SD) 24.1 ± 6.2 27.3 ± 9.6

Mean alcohol consumption

(gr/day)

272 ± 115 284 ± 140

Mean (CIWA-Ar) during the first

week

26.1 ± 6.7 25.7 ± 6.3

M, Male; F, Female; S, Single; M, Married; D, Divorced/separated/widowed; H,

High; M, Middle; L, Low. CIWA-Ar, Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for

Alcohol, Revised.

*All comparisons between groups were non-significant.

Paparrigopoulos et al.BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11:41

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/11/41

Page 3 of 7

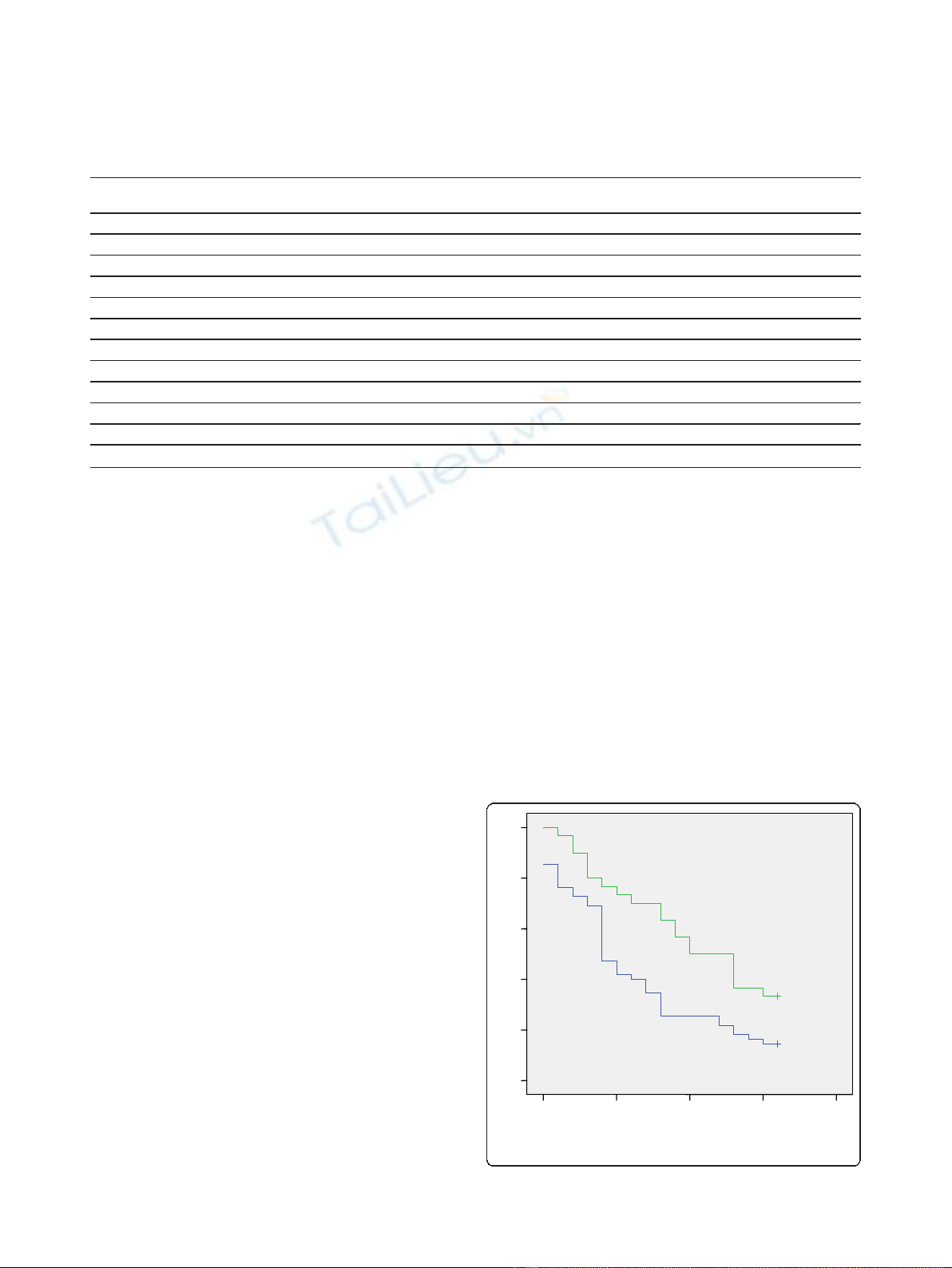

Long-term outcome in terms of abstinence from alco-

hol was better for the topiramate augmentation group.

Thus, although 67 patients in total (78.8%) had relapsed

to alcohol use by the end of the study (16 weeks after dis-

charge), relapse rate was significantly lower in the topira-

mate group (66.7%) compared with the control group

(85.5%) (p = 0.043). Also, median duration of abstinence

in the topiramate group was significantly longer com-

pared to the non-medicated group (10 weeks vs. 4 weeks;

log rank test, p = 0.008, Figure 1). Cox proportional

hazard model showed that risk of relapse was 56% lower

among patients receiving topiramate compared to con-

trols (HR = 0.515, 95% CI: 0.304 - 0.874, p = 0.014).

Reported adverse effects are presented on Table 3.

A considerable proportion (> 10%) of the topiramate aug-

mentation group had some adverse effects, but no significant

difference was recorded compared with the control group,

except for somnolence which was significantly more frequent

in the topiramate group (23.3% vs. 5.4%). All adverse effects

were tolerable and there were no dropouts from the study.

Discussion

The main finding of the present study is that low-dose

topiramate given as a treatment adjunct is well-accepted

and effective in reducing craving for alcohol and symp-

toms of anxiety and depression during the early phase

of alcohol withdrawal. Furthermore, topiramate com-

bined with a psychotherapeutic intervention improves

abstinence from drinking during the first 16-week post-

detoxification period, in comparison with alcohol-depen-

dent individuals receiving psychotherapy alone.

Although topiramate is not currently approved for the

treatment of alcohol dependence [27], several rando-

mized double-blind placebo-controlled trials have

demonstrated its efficacy in improving drinking beha-

viour and maintaining abstinence [28-30]. Compared to

the standard medications approved for alcohol depen-

dence, topiramate has been found to be inferior to disul-

firam in terms of days to relapse [31] and superior to

naltrexone in reducing craving [32] and improving some

other critical measures of drinking behaviour [30]. The

Table 2 Mean scores ± SD of the various measures of psychopathology and craving at the different time points of

assessment (time 0 ®time 2) in the control and the topiramate augmentation group

Variable

(Mean ± SD)

Group 1

st

Assessment (time 0) 2

nd

Assessment

(time 1)

3

rd

Assessment

(time 2)

HDRS

Controls 38.7 ± 7.6 15.9 ± 8.6+ 8.1 ± 6.6∞

Topiramate 39.6 ± 5.5 12.5 ± 3.1*+ 4.9 ± 3.1*∞

HARS

Controls 30.5 ± 10.2 13.9 ± 6.7+ 7.1 ± 6.2∞

Topiramate 31.8 ± 5.3 10.9 ± 3.6*+ 4.3 ± 3.8*∞

GAS

Controls 46.7 ± 5.1 75.6 ± 9.3+ 85.4 ± 8.5∞

Topiramate 46.6 ± 4.7 74.3 ± 6.7+ 84.3 ± 5.6∞

OCDS

Controls 37.2 ± 8.3 17.3 ± 3.9+ 13.3 ± 2.8∞

Topiramate 37.6 ± 7.8 15.3 ± 3.9*+ 10.3 ± 3.1**∞

Statistics: Between groups (independent samples t-test); within groups (RMANOVA).

*Significant difference between controls and topiramate augmentation group (< 0.05).

** Significant difference between controls and topiramate augmentation group (< 0.01).

+ Significant difference between 2

nd

and 1

st

assessment (< 0.01).

∞Significant difference between 3rd and 2nd assessment (< 0.01).

week of relapse

20

15

10

5

0

Cum Survival

1,0

0,8

0,6

0,4

0,2

0,0

Topiramate group

Control group

Figure 1 The cumulative probability function of reaching

16 weeks of abstinence by group.

Paparrigopoulos et al.BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11:41

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/11/41

Page 4 of 7

precise mechanism of topiramate’s favourable action is

unclear. It may be that it modulates GABAergic trans-

mission in the central amygdala, a brain region impli-

cated in the regulation of emotionality and alcohol

intake [33,34]. Also, it has been shown that GABA

receptors undergo allosteric modulation by ethanol and

mediate the acute and chronic effects of alcohol, includ-

ing tolerance, dependence and withdrawal [35]. On the

other hand, topiramate enhances the inhibitory function

of GABA, antagonizes excitatory glutamate receptors,

and inhibits dopamine release [36].

Topiramate has been used for the treatment of alcohol

dependence in outpatient settings. Doses ranging from

150 to 300 mg/day have shown promising results, in terms

of significant improvement in several dependence-related

parameters [3]. However, a major concern has been topir-

amate’s adverse effects, which are prominent especially

during the titration period, appear to be dose-related but

usually subside with continued treatment [37,38]. Thus,

the majority of patients who discontinue topiramate treat-

ment, due to its side effects, do so early in treatment. In

this line of thought, a key objective of the present study

was to establish the efficacy and side effect profile of low-

dose topiramate (up to 75 mg/day) that might improve

adherence to treatment. In our sample, a considerable pro-

portion (> 10%) of the topiramate augmentation group

had some adverse effects, but no significant difference was

recorded compared with the control group. However,

these adverse effects were tolerable and there were no

dropouts from the study. This was probably due to several

reasons such as that the initial detoxification took place in

an inpatient basis assuring a high compliance with all

treatment interventions, that the study population was

highly motivated to withdraw from alcohol, and finally

that our sample consisted of individuals with relatively

high initial withdrawal symptoms who are usually

excluded from most studies of outpatient populations.

Impulsive and compulsive behaviours play a crucial

role in alcohol abuse, craving and relapse [39-41]; there-

fore, medications with anticraving properties have been

used for prevention of relapse. Several studies have

demonstrated topiramate’s efficacy in the management of

impulsive, aggressive and self-harmful behaviour [42],

gambling [43], eating disorders [44], as well as an adjunct

to SSRIs in obsessive-compulsive disorder [45]. Thus,

moderation of impulsivity with consequent minimization

of craving might be responsible for the lower rates of

relapse in the topiramate augmentation group. Moreover,

research has consistently documented a strong associa-

tion between anxiety and/or symptoms of depression and

alcohol abuse; these symptoms usually subside following

a few weeks of abstinence [46]. However, mild anxiety

[11] and minor symptoms of depression may persist for

several months and various medicines - including tiaga-

bine [47], mirtazapine and venlafaxine [12] - have been

used adjunctively to standard alcohol detoxification treat-

ment in order to increase patient compliance and

improve treatment outcome [10,48]. Through such a col-

lateral beneficial action, topiramate could lead to the

more favourable outcome observed in the augmentation

group of the present study.

The main limitations of the present study are: a) the

relatively small sample size, which reduces the statistical

significance of our findings, b) the study did not follow a

double-blind placebo control design; such a design was

not feasible due to the ethical restrictions of our institu-

tion, c) assessment of alcohol use during the follow-up

period was mostly based on self-reports and periodically

cross-checked with an informant and g-GT measurements,

and d) a longer follow-up period would provide important

information on the long term efficacy of topiramate in a

community setting. Despite the above limitations, our

results corroborate previous reports that show the poten-

tial usefulness of topiramate in the treatment of alcohol

dependence even when administered at low doses.

Conclusions

In conclusion, low-dose topiramate when used as an

adjunct to psychotherapy is well tolerated and effective

in reducing alcohol craving, as well as symptoms of

depression and anxiety, present during the early phase

of alcohol withdrawal. Furthermore, topiramate consid-

erably helps to abstain from drinking during the first

16-week post-detoxification period, a period which is

critical for relapse. Thus, topiramate could be an alter-

native option beyond the already approved agents for

the treatment of alcohol dependence.

Abbreviations

GABA: γ-Aminobutyric acid; DSM-IV-TR: Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition, Text Revision; SCAN: Schedules for Clinical

Assessment in Neuropsychiatry; γ-GT: γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; CIDI:

Composite International Diagnostic Interview; HDRS: Hamilton Depression

Rating Scale; HARS: Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale; OCDS: Obsessive

Compulsive Drinking Scale; GAS: Global Assessment Scale; CIWA-Ar: Clinical

Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol, revised; SAFTEE: Systematic

Assessment for Treatment Emergent Events; RMANOVA: repeated measures

Table 3 Reported adverse effects by study group

Topiramate group

N = 30 (%)

Control group

N = 55 (%)

Dizziness 6 (20.0) 4 (7.2)

Somnolence 7 (23.3) 3 (5.4)*

Nervousness 2 (6.6) 7 (12.7)

Numbness/Paresthesias 3 (10.0) 3 (5.4)

Psychomotor slowness 4 (13.3) 2 (3.6)

Nausea 5 (16.6) 2 (3.6)

* Fisher’s Exact Test (2-tailed sig.), p < 0.05.

Paparrigopoulos et al.BMC Psychiatry 2011, 11:41

http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-244X/11/41

Page 5 of 7

![Báo cáo seminar chuyên ngành Công nghệ hóa học và thực phẩm [Mới nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20250711/hienkelvinzoi@gmail.com/135x160/47051752458701.jpg)