Journal of Business Research xxx (xxxx) xxx

Please cite this article as: Zeinab Zaremohzzabieh, Journal of Business Research, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.053

0148-2963/© 2020 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

The effects of consumer attitude on green purchase intention: A

meta-analytic path analysis

Zeinab Zaremohzzabieh

a

,

*

, Normala Ismail

b

, Seyedali Ahrari

b

, Asnarulkhadi Abu Samah

a

a

Institute for Social Science Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia, InfoPort, IOI Resort Jalan Kajang, Puchong, Seri Kembangan, Selangor 43400, Malaysia

b

Faculty of Educational Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia, Selangor 43400, Malaysia

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Meta-analysis

Path analysis

Consumer attitude

Green purchase intention

Structural equation modeling

ABSTRACT

Increasing interests in the development of green purchase intentions have elevated the importance of theories

that explain the relationships between attitudes and intentions. The aim of the present research is to meta-

analytically integrate the model of green purchase behavior (GPB) and the theory of planned behavior (TPB).

We synthesized the research findings of 90 studies (94 samples, n =38622) and employed meta-analytic

structural equation modeling to investigate the empirical fit of the integrated TPB-GPB framework. The find-

ings demonstrated support for the integrated framework and showed mediation role of consumer attitude in the

development of green purchase intent. Moreover, the results suggested that the integrated framework assisted

the TPB model to enjoy huge fertility by integrating the constructs and/or combining with the GPB model to

develop the explanatory power and predictive lenses of green consumer attitudes and green purchase intention.

1. Introduction

In this era, the concerns on global warming, climate change, over-

using natural resources, and air and water pollution have been

increasing, resulting in more consumers becoming conscious of envi-

ronmental degradations confronting them. These environmental deg-

radations have begun to change the lifestyle of the consumers and

business activities, leading to the emergence of green marketing (Larson

et al., 2015). Green marketing within business practices involves pro-

moting sustainable development. It includes the marketing of goods and

services considered to be green, and maintaining and stimulating pro-

environmental consumer behaviors and attitudes (Jain & Kaur, 2004).

This concept of green marketing has also inspired consumers to buy or

acquire green products (Biswas & Roy, 2015). As such, there is no doubt

that the attitudes and behaviors of the consumers are in the process of

shifting (Mintel, 1991). Consumers actively support green products to

maintain sustainable development and reduce their environmental im-

pacts (Oliver, 2013).

The last three decades saw increasing numbers of international firms

engaging in green production, and consumers purchasing and

embracing green products. However, this higher willingness has not

been realized and translated to the actual purchase of green products

(Guyader et al., 2017; Wei et al., 2017). This scenario is also known as

“attitude – behavioral intention gap”. For example, despite the positive

attitude of customers towards green products, a previous study showed

that the mainstream consumers did not purchase green products as

estimated and the market shares of these products were regularly lower

than 4% of the whole sales (Polonsky, 2011). Until now, a large body of

work on the green consumer behavior highlights that consumers are

progressively motivated to purchase green goods (e.g., Arli et al., 2018;

Khan & Kirmani, 2018). The causes for this behavior gap have not been

adequately studied. It is possible that consumers comply with social and

cultural norms that may reflect their purchasing decisions (Nguyen

et al., 2017). However, there may be special barriers and drivers,

particularly in everyday consumptions, which complicate green pur-

chase intention (GPI).

Therefore, to address this matter, many earlier studies have inves-

tigated consumer attitudes and purchasing intentions with regards to

green products by using the theory of planned behavior (TPB) (Joshi &

Rahman, 2016; Yadav & Pathak, 2016). However, most of these studies

expressed absence or weak correlation between positive attitudes and

actual buying behavior. Joshi and Rahman (2015) indicated that the

* Corresponding author at: Institute for Social Science Studies, Universiti Putra Malaysia, InfoPort, IOI Resort Jalan Kajang, Puchong, Seri Kembangan, Selangor

43400, Malaysia.

E-mail addresses: z_zienab@upm.edu.my (Z. Zaremohzzabieh), malaismail@upm.edu.my (N. Ismail), seyedaliahrari@gmail.com (S. Ahrari), asnarul@upm.edu.

my (A. Abu Samah).

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Journal of Business Research

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jbusres

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.10.053

Received 22 May 2019; Received in revised form 9 June 2020; Accepted 22 October 2020

Journal of Business Research xxx (xxxx) xxx

2

TPB failed to capture the relationship between attitudinal variables or

environmental concerns and consumer attitudes that can in fact influ-

ence GPI. Several studies have suggested modifying TPB in order to

overcome its limitations. Joshi and Rahman (2015) specified that the

existing literature on the antecedents of consumer attitudes and GPI has

focused on the TPB constructs and additional factors. Liobikien˙

e and

Bernatonien˙

e (2017) showed the elements and their impact on all green

products purchase and suggested a classification of environmental and

attitudinal factors influencing the purchasing behavior. For this pur-

pose, the model of Green Purchase Behavior (GPB; Sarumathi, 2014) is

adopted because it is one of the models that explain the reasons behind

the observed attitude-behavior gap with regards to green products. The

model predicts and explains consumer attitudes using motivational

factors which in turn lead to GPI.

To date, many scholars have further examined frameworks that bring

together at least one of the key antecedents of the GPB and at least one of

the antecedents of the TPB in the empirical literature on GPI (e.g., Lin &

Niu, 2018). Some studies applied the TPB and GPB constructs as com-

parable factors of consumer attitudes and purchasing intention in green

consumption models while some of these studies examined structural

models (e.g., Yadav & Pathak, 2016). Some studies particularly used

statistical procedures to examine the mediation role of the GPB con-

structs based on direct and indirect effects (e.g., Maichum et al., 2017b;

Paul et al., 2016).

To our knowledge, there are no earlier studies to date that investigate

all antecedents included in the GPB and TPB to uncover attitu-

de–behavioral intentions of green consumption. Thus, the relative

novelty of the quantitative review of the substantive area of customer

attitude and the GPI research, and the absence of studies examining

relationships between the constructs of the GPB and TPB within a single

theoretical framework provided the motivation and rationale for un-

dertaking this study. The first goal of the present study was to deliver a

clear demonstration of applying meta-analytic methods combined with

structural equation modeling (MASEM) to integrate the TPB and GPB in

order to investigate direct and indirect effects of consumer attitudes and

their antecedents on GPI. The insights driven from this analysis could

inform the structure of the integrated TPB-GPB framework, and verify

the explanatory and predictive adequacy of this integrated framework to

advance the knowledge of this field. Second, we examined the effects of

contextual (culture) and methodological moderators on our proposed

framework. The MASEM technique enabled us to investigate whether

differences across studies were caused by cultural context or methodo-

logical moderators.

2. Consumer attitudes and purchasing intention of green

products: An extended TPB

In the academic literature, words like “green purchasing”, “green

acquisition”, and “environmentally responsible purchasing” are used to

explore consumer green purchasing behavior. Green purchasing, as

described by Chan (2001), is acquisitioning services and goods that

minimize damage to the environment. It is most often reflected by GPI,

which is the consumers’ intention to purchase and pay for green prod-

ucts. Motivational factors influence these intentions, changing the con-

sumers’ buying behaviors towards green products (Joshi & Rahman,

2015). Peter (2011) defined green products as fulfilling the consumers’

requirements and necessities without damaging the environment. Chen

(1993) argued that a green product reduced its environmental impacts

at each phase of its life cycle. In that sense, his definition was based on

the whole production process rather than the product itself. Recently,

Sdrolia and Zarotiadis (2019) categorized green products as tangible

and intangible products that reduced its impact on the environment

either directly or indirectly during its whole life cycle, as subjected to

the current technology and science. This is a clear indication that the

definition of green product should be holistic.

Many studies indeed analyzed the antecedents of GPI as a whole,

including all green products into one term (e.g., Chaudhary & Bisai,

2018; Yadav & Pathak, 2016). In these studies, the TPB serves as the

basis for the integrated framework to explore GPI. The three main an-

tecedents of the TPB which are relevant to GPI are attitudes, subjective

norms and perceived behavior control (Nguyen et al., 2019). Attitude

can be described as the inner feeling of favorableness or otherwise that a

consumer has towards a green product or green marketing. Subjective

norms (one of the social norms) are the perception of a consumer on the

social pressure on whether or not to perform GPB. Lastly, perceived

behavior control reflects a consumer’s viewpoint on the convenience or

difficulty to perform green purchasing behavior.

Meanwhile, the TPB does not consider the influences of motivational

factors on consumer attitudes and decisions to purchase green products

(Joshi & Rahman, 2015). Meanwhile, the GPB complements TPB’s

constructs with environmental beliefs, knowledge, concern, conscious-

ness, and awareness in explaining why a consumer’s attitudes and

purchasing intentions might lead to green products to get the real grasp

on the attitude-behavioral intention relationship. Cary (1993) stated

that environmental beliefs gave rise to cultural symbolic beliefs

reflecting the individuals’ development of passionate beliefs about

environmental issues. External factors like environmental knowledge

refer to the individual’s capability to assess the impacts of environment

and ecosystems on the society, and an individual’s amount of knowledge

on environmental issues, including the problems, causes, solutions and

others (Aini et al., 2007). Besides that, the influences of human behavior

on the environment shows the individual’s environmental awareness

(Kollmuss and Agyeman, 2002). This internal factor comprises “cogni-

tive and knowledge-based” element and “affective and awar-

eness-based” element. Hassan (2014) defined environmental concern as

the degree of the consumers’ worry about environmental threats caused

by human interventions and their intentions to contribute to the solu-

tions of these issues. Environmental consciousness (a part of the social

consciousness) is one of the internal factors that reflect the psychological

variables relating to individuals’ propensity to involve in

pro-environmental behaviors (Sharma & Bansal, 2013). Environmental

consciousness is also a complex nature of values, affective responses,

personality features and attitudinal discourse (Kautish & Sharma, 2018).

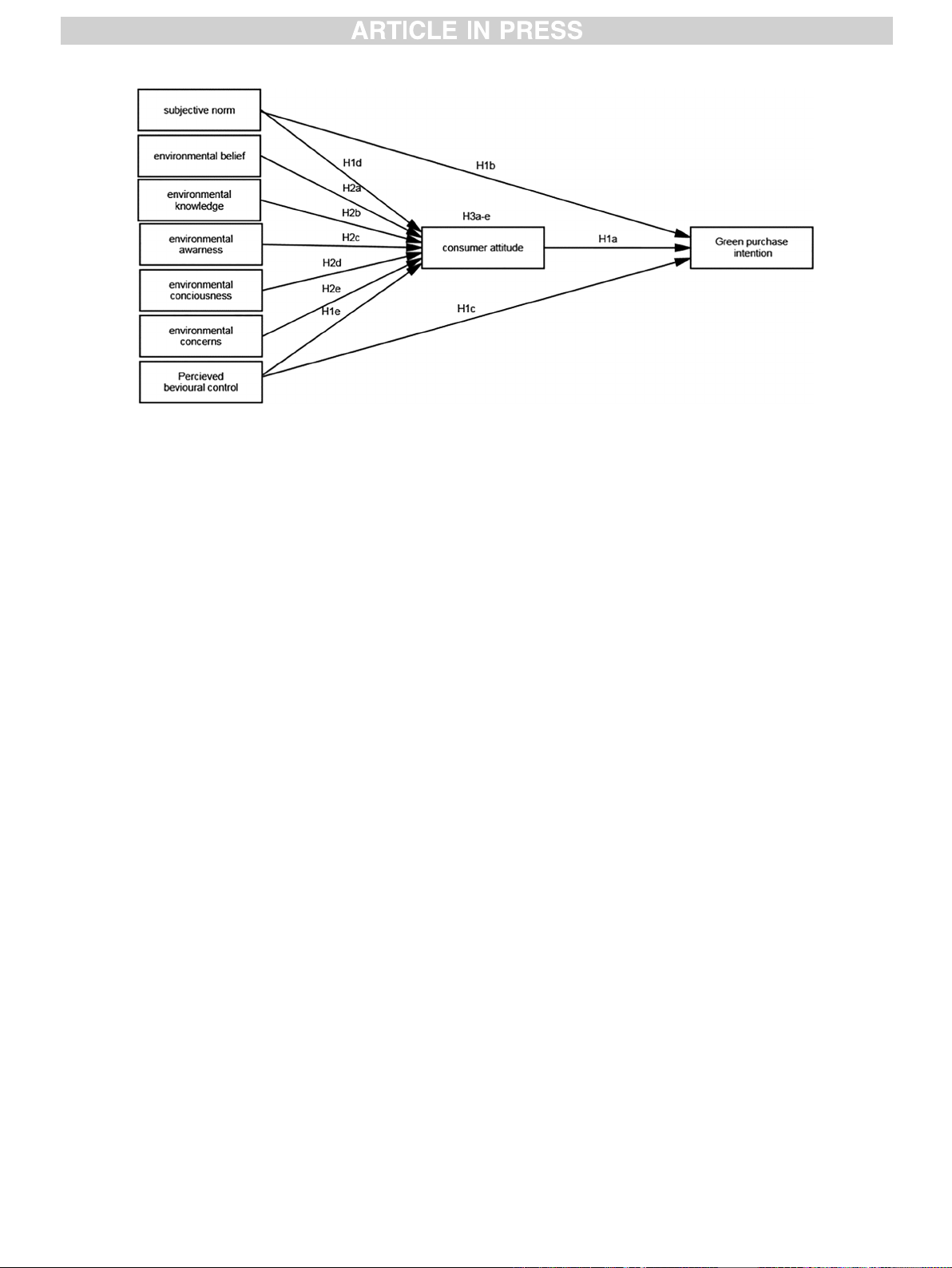

Thus, the integrated TPB-GPB framework (Fig. 1) and the hypothesized

relationships were developed as described below.

2.1. The effects of TPB constructs on consumer attitude and GPI

Within the framework of consumer green purchasing behavior, there

were several investigations using the TPB constructs to examine the

antecedents of GPI in general (Liobikien˙

e et al., 2016; Paul et al., 2016;

Yadav & Pathak, 2017) while some other studies partially supported the

TPB (e.g., Chou, et al., 2012; Kim et al., 2013). Moreover, some studies

have found that the TPB constructs can serve as direct determinants of

GPI (Bong Ko and Jin, 2017; Paul et al., 2016). Similarly, Maichum et al.

(2016) employed the TPB towards the green consumption in Thailand,

showing that consumer attitudes, subjective norms, and perceived

behavior control have significant direct positive influences on GPI.

Interestingly, a study done in India (Sreen et al., 2018) found a signifi-

cant relationship between consumer attitude towards green products

and subjective norms. The study has also proven the relationship be-

tween consumer attitude towards green products and perceived

behavior control. Overall, the findings from the previous studies

demonstrate the function of TPB model to provide a clear grasp of the

intention of green consumption. Therefore we hypothesize the following

based on these three independent constructs of TPB and the above

arguments:

Hypothesis 1a.. There is an association between consumer attitude

towards green products and GPI.

Hypothesis 1b.. There is an association between subjective norms and

GPI.

Z. Zaremohzzabieh et al.

Journal of Business Research xxx (xxxx) xxx

3

Hypothesis 1c.. There is an association between perceived behavior

control and GPI. Hypothesis 1d. There is an association between sub-

jective norms and consumer attitude towards green products.

Hypothesis 1e.. There is an association between perceived behavior

control and consumer attitude towards green products.

2.2. The GPB constructs and their effects on consumer attitude towards

green products

Along the lines of the above arguments, we attempted to create the

integrated framework that combines the best features of TPB and GPB.

Out of the eight factors in this proposed framework, five antecedent

factors were the considerable predictors of consumer attitude as sug-

gested in GPB model: environmental beliefs, knowledge, concern, con-

sciousness, and awareness.

Even though previous studies on the subject supported the constructs

of GPB into GPI, some studies observed that these constructs concep-

tually affected consumer attitude towards green products. For example,

a previous study indicated that a positive attitude towards green prod-

ucts was appreciably influenced by environmental beliefs because gen-

eral perspectives were particularly enough to prompt GPI (Khaola et al.,

2014). In such cases, there is a ‘beliefs–attitude–intention gap’ as it is

inevitable that individual consumers who hold strong environmental

belief in buying green products would have strong attitude towards the

behavior and be more likely to be involved in environmental-oriented

purchasing intentions. Kalafatis et al. (1999) also indicated that envi-

ronmental beliefs can influence consumer attitude which in turn can

influence GPI. Therefore:

Hypothesis 2a. There is an association between environmental beliefs

and consumer attitude towards green products.

Furthermore, environmental ethics came into prominence during the

Earth Day 1990, emphasizing on individual responsibilities and envi-

ronment quality. Individual responsibilities include an informed con-

sumer who is able to make decision. This, in turn, requires

environmental knowledge and awareness. Environmental knowledge

and awareness directly influence consumer attitude towards green

products. Despite being told that green products are credence goods,

consumers may not recognize whether the product is green or not even

after repeating the purchase. Thus, environmental knowledge and

awareness of consumers are critical in consumer attitudes towards green

products. Particular findings have proven the relationships between

environmental knowledge, awareness and consumer attitude, which has

further effects on GPI (e.g., Akbar et al., 2014; Haryanto, 2014; Kumar

et al., 2017). A study by Noor et al. (2012) found that environmental

knowledge and awareness with regards to the environmental degrada-

tion have a significant role in shaping the consumer attitude towards

green products. As a result, these empirical studies have developed the

paradigm of awareness or knowledge-attitude-intention, showing a

positive relationship between environmental knowledge, attitudes, and

awareness; the more environmental knowledge and awareness a con-

sumer has, the more positive attitudes are shown towards green prod-

ucts, resulting in GPI. Thus:

Hypothesis 2b. There is an association between environmental

knowledge and consumer attitude towards green products.

Hypothesis 2c. There is an association between environmental

awareness and consumer attitude towards green products.

Environmental consciousness, one of the internal constructs in the

GPB, has induced an intense discussion in the literature. Lately, the

integration of sustainability elements and the consequent green claims

for products have become appealing to individual consumers who

emphasize on environmental consciousness. Some researchers have

confirmed the significant association between environmental con-

sciousness and consumer attitude in green marketing domain. For

example, a green study done by Mishal et al. (2017) discovered positive

association between environmental consciousness and consumer atti-

tude towards green products. Therefore:

Hypothesis 2d. There is an association between environmental con-

sciousness and consumer attitude towards green products.

In the proposed framework, environmental concerns also remain as

the important antecedents of consumer attitude. Hartmann and Apao-

laza-Ib´

a˜

nez (2012) concluded that consumers having positive attitudes

and environmental concerns were more likely to be involved in green

consumer behaviors compared to consumers who were not pro-

environmentally concerned. Besides that, several studies have proven

the association between consumer attitude and environmental concern

(Hanson, 2013; Maichum et al., 2016; Mostafa, 2007; Tang et al., 2014;

Yadav & Pathak, 2016). Based on this review, we hypothesized that:

Hypothesis 2e. There is an association between environmental

concern and consumer attitude towards green products.

2.3. Mediating role of consumer attitude towards green products

There is the direct association of consumer attitude towards green

Fig. 1. An integrated framework for consumer attitude and green purchase intention.

Z. Zaremohzzabieh et al.

Journal of Business Research xxx (xxxx) xxx

4

products and GPI as proven in many prior research studies in which the

relationship has been found significant. Meanwhile, Sarumathi (2014)

showed the role of motivational factors to determine the consumer

attitude in the GPB model. Thus, the GPB model studies the mediating

effect of consumer attitude to elucidate the association of GPI with the

antecedent factors engaged in the formation of attitude. Recently, the

mediating effect of consumer attitude on the behavioral intention has

been confirmed in the field of green consumer behavior research (Paul

et al., 2016).

Research conducted on green consumption has also validated the

association between attitudes and behavioral intentions in both Western

and non-Western countries. For instance, Tang et al. (2014) examined

the antecedent factors that influenced the Chinese consumer attitude

towards green products and how such attitude mediated the impacts of

these factors on GPI. The findings indicated that environmental concerns

together with environmental beliefs influenced consumer attitude to-

wards green produces. This finding has mediated the effect of such

concern and beliefs on GPI. In Thailand, Maichum et al. (2017b) also

found that attitudes mediated the association between environmental

knowledge and GPI. Similarly, previous studies also indicated that

attitude mediated the influence of environmental concerns on GPI

(Aman et al., 2012; Khaola et al., 2014; Paul et al., 2016). In another

study, Assarut and Srisuphaolarn (2010) demonstrated that the degree

of individual’s environmental consciousness had no direct influence on

purchasing intentions but it indirectly affected the purchasing intentions

through attitudes towards green products. Therefore, for the purpose of

explaining the said phenomena, we proposed that:

Hypothesis 3a. Consumer attitude mediates the association between

environmental beliefs, and GPI.

Hypothesis 3b. Consumer attitude towards green products mediates

the association between environmental awareness and GPI.

Hypothesis 3c. Consumer attitude towards green products mediates

the association between environmental knowledge and GPI.

Hypothesis 3d. Consumer attitude towards green products mediates

the association between environmental consciousness and GPI.

Hypothesis 3e. Consumer attitude towards green products mediates

the association between environmental concern and GPI.

2.4. Potential moderators

The studies included in the present MASEM have been performed in

diverse time periods and in several countries with several types of socio-

cultural backgrounds. The time periods and countries considered in the

included studies varied in terms of several features and respective

environment aspects. Therefore, recognizing moderator variables was

vital in this MASEM as doing so helped uncover the situations under

which GPI was most effective on consumers’ green purchasing behavior.

In the development of GPI, vigorous alterations in the macro environ-

ments such as global landscape affect the consumers. Dahl (2000) rec-

ommended cultural influences because consumers tended to explain

their social contexts locally instead of globally. Therefore, in order to

create an effective link to the local consumers, corporations need to have

full knowledge of the local environment (country), especially due to the

presence of cultural differences within each country. Recently, many

studies (e.g., Ritter et al., 2015; Sreen et al., 2018; Vicente-Molina et al.,

2013) stated that cross-country disparities focusing on national cultures

moderate the association between GPI and its antecedents.

Furthermore, Schepers and Wetzels (2007) recommended three

methodological moderators which might influence the associations be-

tween different constructs in meta-analysis: publication date, respon-

dent type and publication status. In this way, we planned to consider the

possible moderators of the relationship between the constructs of TPB

and GPB by evaluating how the size of the relationship differentiated

depending on culture, respondent type, publication date and the type of

publication evaluated.

3. Method

3.1. Literature research

Five steps were taken to determine the samples of unpublished and

published materials that empirically examined the association between

antecedent factors and consumer attitude towards green products and

their purchasing intention.

Firstly, we consulted articles reviewed previously (e.g., Groening

et al., 2018; Joshi & Rahman, 2015; Kumar & Polonsky, 2017;

Liobikien˙

e & Bernatonien˙

e, 2017; Scalco et al., 2017; Tiwari, 2014).

Secondly, searches were conducted using multiple electronic databases

(i.e. Google scholar, Scopus, EBSCO, Directory of Open Access Journal,

Science Direct, SpringerLink, JSTOR, Emerald, ProQuest, and Business

Source Complete) to identify entries released and printed between 1992

and February 2019.

In the third stage, the search terms included the exact word “green

product” and the variant of the word “purchase”. We formed a two-part

search enquiry: “green” “purchase”. The search results for the two parts

were manually checked to find additional studies for inclusion and the

literature search was limited to “green” in addition to intentional and

actual purchase behaviors. The literature scrutinized the following

concepts of purchasing behavior: willingness to pay, consumer attitudes

and purchasing intention or behavioral intention to purchase. In the

fourth stage, we conducted searches using keywords similar to consumer

attitudes and its antecedents, and the effect on purchasing or buying

intentions in line with the constructs of TPB and the GPB. In the final

stage, we performed an unstructured search by utilizing Google in order

to find more relevant studies.

When coding the data, the description and measurement of each

construct were utilized instead of the constructs’ name in the original

studies, and each construct was coded. Consumer perceptions of green

products were assessed in comparison to non-green products, whether

the green products were environmentally friendly, non-toxic, safe to be

consumed and good for the planet than the non-green products. The GPI

was assessed by intention and willingness of the consumers in pur-

chasing green products. For instance, “I intend to buy green products in

the near future” (Chen & Chang, 2012). In addition to that, we used a

binary variable to assess cultural and methodological moderators. For

cultural context, we classified studies that were conducted in non-

Western countries (0) and Western countries (1). We coded the publi-

cation dates of the earlier publications between 1992 and 2010 (0) and

current publications from 2010 onwards (1). Respondent types included

consumer (0) and non-consumer (1). Finally, we coded publication

status as journal articles (1) and non-journal articles (0). The data was

extracted and checked by two reviewers and then reported in Table 1.

3.2. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

A total of 17,600 results were generated through searching using

keywords as they included all articles containing any of the keywords.

However, when filtration of English language, peer- reviewed journals

or articles and exact phrases were applied, the entries then were reduced

to 677. Upon further filtration using a quantitative method in dealing

with the integrated model related to the constructs of TPB and GPBM,

the papers were subsequently reduced to 253. For the remaining data-

bases, the panel further filtered the articles on the basis of either p-

values or correlation coefficients. These data must be included to

conduct the path analyses of meta-analytic effects. After removing five

duplicate studies, 90 articles reporting 94 data sets met the inclusion

criteria in the meta-analysis procedure, giving a total of 38,622 partic-

ipants. In total, 82 journal articles, one unpublished paper, four disser-

tations and three proceeding conference papers met the inclusion

Z. Zaremohzzabieh et al.

Journal of Business Research xxx (xxxx) xxx

5

Table 1

Summary of Studies Included in the meta-analytic structural equation modeling.

No. Author(s) K N Publication Type Respondent Type Culture Country

1 Kalafatis et al. (1999) 2 175/170 JA Consumers W UK/Greece

2 Chan (2001) 1 549 JA Consumers N-W China

3 Chan and Lau (2002) 1 232/213 JA Consumers N-W& W China/US

4 Mostafa (2007) 1 1093 JA Students N-W Egypt

5 Assarut and Srisuphaolarn (2010) 1 319 JA Undergraduate students N-W Thailand

6 Ali et al. (2011) 1 400 JA University students N-W Pakistan

7 Promotosh and Sajedul (2011) 1 282 D Students W Sweden

8 Aman et al. (2012) 1 384 JA Consumers N-W Malaysia

9 Lee et al. (2012) 1 112 JA Consumers N-W Malaysia

10 Wong et al. (2012) 2 150/150 D Consumer N-W Malaysia/Singapore

11 Abbasi et al. (2013) 1 150 JA Consumers N-W Pakistan

12 Azizan and Suki (2013) 1 430 JA Consumers N-W Malaysia

13 Rehman and Dost (2013) 1 180 CP Students N-W Pakistan

14 Rizwan et al. (2013) 1 200 JA Consumers N-W Pakistan

15 Samarasinghe and Samarasinghe (2013) 1 238 JA Consumers N-W Sri Lanka

16 Vazifehdoust et al. (2013) 1 374 JA Consumers N-W Iran

17 Akbar et al. (2014) 1 160 JA Consumers N-W Pakistan

18 Anvar and Venter (2014) 1 200 JA Students N-W South Africa

19 Ayoun et al. (2014) 1 420 UP Consumers N-W Algeria

20 Hasnah Hassan (2014) 1 140 JA Muslim consumers N-W Malaysia

21 Irandust and Bamdad (2014) 1 290 JA Students N-W Iran

22 Kongkajaroen et al. (2014) 1 220 JA Consumers N-W Thailand

23 Lao (2014) 1 909 JA Consumers N-W China

24 Lu et al. (2014) 1 458 CP Consumers N-W Malaysia

25 Khaola et al. (2014) 1 200 JA Shopper N-W Lesotho

26 Pagiaslis and Krontalis (2014) 1 1695 JA Households W Greece

27 Ryan (2014) 1 325 D Consumers W US

28 Tang et al. (2014) 1 408 JA MBA students N-W China

No. Author(s) K N Publication Type Respondent Type Culture Country

29 Wang (2014) 1 1866 JA Consumers N-W Taiwan

30 Wu and Chen (2014) 1 560 JA Consumers N-W Taiwan

31 Zhao et al. (2014) 1 500 JA Consumers N-W China

32 Ahmad and Thyagaraj (2015) 1 270 JA Consumers N-W India

33 Bhatt and Bhatt (2015) 1 244 JA University students N-W India

34 Choi and Cho (2015) 1 101 JA Consumers N-W South Korea

35 Gorokhova (2015) 1 176 D Customers W Norway

36 Karatu and Nik Mat (2015) 1 102 JA Lectures N-W Nigeria

37 Mark and Law (2015) 1 457 JA Consumers N-W Hong Kong

38 Sharaf et al. (2015) 1 191 JA Students N-W Malaysia

39 Ali and Ahmad (2016) 1 377 JA Consumers N-W Pakistan

40 Achchuthan and Velnampy (2016) 1 1325 JA Undergraduate N-W Sri Lanka

41 Braga Junior et al. (2016) 1 905 JA Consumers N-W Brazil

42 Chen and Hung (2016) 1 406 JA Consumers N-W Taiwan

43 Chen and Deng (2016) 1 306 JA Consumers N-W China

44 Dhurup and Muposhi (2016) 1 386 JA Students N-W South Africa

45 Goh and Balaji (2016) 1 303 JA Retail shoppers N-W Malaysia

46 Kai and Haokai (2016) 1 1355 JA Consumers N-W China

47 Malik and Singhal (2016) 1 302 JA Consumers N-W India

48 Maichum et al. (2016) 1 483 JA Consumers N-W Thailand

49 Paul et al. (2016) 1 521 JA Consumers N-W India

50 Uthamaputhran et al. (2016) 1 375 JA Students N-W Malaysia

51 Yadav and Pathak (2016) 1 326 JA Consumers N-W India

52 Butt (2017) 1 574 JA Students N-W Pakistan

53 Chelliah et al. (2017) 1 120 JA University students NW Malaysia

54 Diyah and Wijaya (2017) 1 202 JA Housewives N-W Indonesia

55 Eles and Sihombing (2017) 1 200 JA University students N-W Indonesia

56 Liu et al. (2017) 1 249/425 JA Consumers W US (non-Hispanic Whites Hispanic adults)

No. Author(s) K N Publication Type Respondent Type Culture Country

57 Lee (2017) 2 357/398 JA Consumers N-W Korea & China

58 Haider and Kakakhel (2017) 1 462 JA Consumers N-W Pakistan

59 Mai and Linh (2017) 1 352 JA Consumers N-W Vietnam

60 Mahmoud et al. (2017) 1 341 JA University students N-W Sudan

61 Maichum et al. (2017a) 1 425 JA Consumers N-W Thailand

62 Maichum et al. (2017b) 1 412 JA Consumers N-W Thailand

63 Mishal et al. (2017) 1 500 JA Households N-W India

64 Rahmi et al. (2017) 1 150 JA Consumers N-W Indonesia

65 Sharma and Aswal (2017) 1 224 JA Consumers N-W India

66 Wei et al. (2017) 1 375 JA Consumers N-W Taiwan

67 Yadav and Pathak (2017) 1 620 JA Consumers N-W India

68 Al Mamun et al. (2018) 1 380 JA Low-income household N-W Malaysia

69 Arli et al. (2018) 1 916 JA Consumers N-W Indonesia.

70 Chaudhary and Bisai (2018) 1 202 JA Students N-W India

(continued on next page)

Z. Zaremohzzabieh et al.