https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244020902074

SAGE Open

January-March 2020: 1 –10

© The Author(s) 2020

DOI: 10.1177/2158244020902074

journals.sagepub.com/home/sgo

Creative Commons CC BY: This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License

(https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) which permits any use, reproduction and distribution of

the work without further permission provided the original work is attributed as specified on the SAGE and Open Access pages

(https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/open-access-at-sage).

Original Research

Introduction

Climate change, industrial pollution, and excessive personal

consumption have all been increasingly affecting the environ-

ment and bringing progressively harsher effects on human

life (Carfora et al., 2017; Thøgersen, 2009). Meanwhile, peo-

ple’s awareness over the importance of environmental protec-

tion has been growing, so much so that it, alongside the goal

to achieve sustainable development, has been slowly turning

into a consensus among nations worldwide. Governments

and enterprises, as important economic entities, have started

an endeavor toward environmental protection by changing

production methods, developing green products, and adjust-

ing environmental protection policies. However, consumers’

role in environmental protection cannot be ignored; past

research showed that a reduction in environmental hazards

produced by consumers by increasing pro-environmental

consumption behavior was a very significant step toward

environmental protection. Thus, the role of pro-environmen-

tal consumption behavior is very important in the establish-

ment and maintenance of environmental protection.

Mainieri et al. (1997) defined pro-environmental con-

sumption behavior as a type of volunteer behavior that con-

sciously seeks to tackle environmental issues, such as climate

change, global warming, and environmental degradation.

This type of behavior has been shown to minimize the nega-

tive impact of one’s actions in the environment through the

purchase of organic products that are environmentally bene-

ficial (Mainieri et al., 1997). Typical pro-environmental con-

sumption behaviors include the purchase of environmentally

responsible products that minimize environmental impact,

products from firms with good environmental reputations,

and/or products produced using biodegradable, carbon neu-

tral or recycled inputs, and so on (Cleveland et al., 2012).

Many studies have analyzed pro-environmental consump-

tion behaviors from multiple perspectives, and, although

pro-environmental consumer behavior has been more widely

studied in recent years, there are still major research prob-

lems in the subject; we believe that the key to resolve this

problem does not lie within the understanding of what this

type of behavior is or how to activate it—topics often

902074SGOXXX10.1177/2158244020902074SAGE OpenWang et al.

research-article20202020

1Zhejiang University of Finance & Economics, Hangzhou, China

Corresponding Author:

Jian Gao, School of Business Administration, Zhejiang University of

Finance & Economics, Hangzhou 310018, China.

Email: jettgao@zufe.edu.cn

Effect of Green Consumption Value

on Consumption Intention in a Pro-

Environmental Setting: The Mediating

Role of Approach and Avoidance

Motivation

Jianguo Wang1, Jianming Wang1, and Jian Gao1

Abstract

Based on the theory of consumer values, this study aimed to examine the relationship between green consumption values and

pro-environmental consumption intention by establishing a “value-motivation-intention” model and to check the moderation

effect of green involvement. In total, 741 shoppers were recruited. Data analyses showed that (a) green consumption values

positively influenced pro-environmental consumption intention; (b) the behavioral approach system positively influenced

pro-environmental consumption intention, but the behavioral inhibition system did not; (c) the behavioral approach system

positively mediated the relationship between green consumption values and pro-environmental consumption intention; and

(d) green involvement positively moderated the relationship between green consumption values and pro-environmental

consumption intention.

Keywords

green consumption values, pro-environmental consumption intention, behavior activation system, behavior inhibition system

2 SAGE Open

explored in previous literature. We identified the research

gap by this question: How do we make pro-environmental

consumption behavior become not a short-term but a long-

term behavior?

Previous research has found that people’s values are posi-

tively related to pro-environmental consumption behavior

(Stern, 2000). Stern (2000) suggested the values–belief–

norm theory and divided people’s values into three catego-

ries: egoism values, altruistic values, and biological values;

the same author also discussed the relationship between

these values and pro-environmental behavior. Chan (2001)

used evidence from Chinese consumers and discussed the

effect of a man–nature orientation on pro-environmental

behavior. Furthermore, people’s values are a relatively stable

state of mind, as they tend to remain the same for a certain

period of time. Therefore, it is necessary to analyze the rela-

tionship between values and pro-environmental consump-

tion behavior as well as the role of consumer contextual

factors and personal traits.

Thus, this study primarily aimed to explore the mecha-

nisms behind the relationship between green values and pro-

environmental consumption behavior, and to analyze the

mediating effect of approach and avoidance motivation on

consumers’ psychological motivation characteristics when

purchasing pro-environmental products.

This study secondarily aimed to explore the moderating

effect of green involvement (GI) and analyzed the differ-

ences between consumers who have different levels of GI.

Theoretical Background and

Hypotheses

Pro-Environmental Consumption Behavior

Recently, pro-environmental consumption behavior has been

receiving increasing attention in the literature (Lacroix,

2018; Lange & Dewitte, 2019; Mainieri et al., 1997; Maio &

Wei, 2013; Moser, 2015; Steinhorst & Klöckner, 2018;

Urban et al., 2019; Welsch & Kühling, 2009). This focus is

consistent with an increasingly broader interest in under-

standing pro-environmental behavior that has persisted for

several decades (e.g., Hines et al., 1987; Kollmuss &

Agyeman, 2002; Lange et al., 2018). Overall, such studies

mainly focused on achieving harmony between man and

nature through the realignment of consumer behavior, and

they have mostly sought to understand the differences among

individual consumers regarding their pro-environment con-

sumption behavior. Some of these studies have focused on

finding pro-environmental consumers and segmenting them

in the market, something that can be illustrated by some

researches’ description of pro-environmental consumers:

They regard that these consumers are mostly female and

older, and have more income and higher educational levels.

Nonetheless, these same studies were limited in the sense

that they did not analyze why and how pro-environmental

consumption behavior is generated.

Therefore, other studies have tried to solve this problem and

turned their research perspectives into understanding how pro-

environmental consumption behavior can be promoted: One

study identified that both psychological and contextual factors

are important variables affecting pro-environmental consump-

tion behaviors (Ertz et al., 2016). Specifically, the psychologi-

cal factors that predict pro-environmental consumption

behavior include environmental attitude, social norms, motiva-

tion, perceived value (Gifford & Nilsson, 2014; Miao & Wei,

2013), and personal ethics (Bamberg, 2003). Regarding the

contextual factors, they include interpersonal relationships,

laws, and the convenience of recycling facilities; the stimula-

tion of consumers’ perceptions regarding such contextual fac-

tors was shown to be able to change their psychological factors,

thereby producing actual pro-environmental consumption

behavior (Guagnano et al., 1995; Steg & Vlek, 2009; Stern,

2000). In sum, this means that pro-environmental consumption

behavior is a result of the interweaving between psychological

and contextual factors. Notwithstanding, there are few studies

exploring which elements among these factors enable the con-

tinuous promotion of pro-environmental consumption behav-

ior, so it is a topic that requires further examination.

Theory of Consumption Values

Based on the theory of consumption values, green con-

sumption values (GCVs) were defined as one’s tendency to

express its own environmental protection values through

his or her purchases and consumption behavior (Haws

et al., 2014). Many researchers suggested that consumers’

GCVs are an important factor that guides consumer behav-

ior and affects their preference regarding which goods and

services they access in a pro-environmental context

(Candan & Yıldırım, 2013; Gonçalves et al., 2016). Another

study showed that the pro-environmental outcomes of one’s

GCVs are achieved through intrinsic and extrinsic factors

that are associated with the components of a given purchase

(Biswas & Roy, 2015). This finding suggested that GCVs

are part of a more extensive nomological network associ-

ated with conversations beyond environmental resources; it

emphasized three facets of consumer choice behavior: (a)

consumer choice of what to buy and what not to buy, (b)

consumer choice of preferring one type of product to

another, and (c) consumer selection between different

brands. Consumers with stronger GCVs would be more

conscientious in the use of financial and physical resources

(Biswas & Roy, 2015).

Regarding financial resources, past research suggests that

green consumption (or conservation) may be related to con-

cerns regarding spending money (e.g., family size).

Regarding physical resources, consumers that are more

aware of green consumption may try to use products in their

entirety and try not to use more than the necessary amount,

all with the intent for the product to effectively perform its

function (Haws et al., 2014). Furthermore, one’s GCVs have

remained unchanged for a period of time.

Wang et al. 3

Pro-Environmental Consumption Behavior

and GCVs

Many studies suggested that value was a critical influential

factor of pro-environmental consumption behavior. Stern

(2000) subdivided pro-environmental consumption behavior

into two categories according to their environmental impact

during the stages of production and consumption: green con-

sumerism and the purchase of major household goods and

services. These categories denote that pro-environmental

consumption behavior not only relied on the actual behavior

but also guided by one’s inner values.

De Groot and Steg (2015) suggested that individuals with

environmental values, such as apathy for nature, personal

inclination toward preserving the planet, and ecocentric phi-

losophies, were more committed to displaying pro-environ-

mental behaviors. Nguyen et al. (2016) found that biospheric

values can influence pro-environmental consumption behav-

ior; other research supported this same conclusion, for

instance, Qasim et al.’s (2019) research subdivided people’s

values into social value, conditional value, epistemic value,

and emotional value. By doing so, they found that condi-

tional value, emotional value, and epistemic value had a sig-

nificant positive influence on consumers’ behavioral

intention to consume organic food.

Behavioral intention is regarded as an important predictor

of actual behavior (Ajzen, 1991). Pro-environmental con-

sumption behavior is the practical expression of one’s pro-

environmental consumption intention (PCI). Thus, it can be

said that the stronger the PCI, the more likely the actual pro-

environmental consumption behavior will occur. Therefore,

pro-environmental consumption behavior was replaced by

PCI as an outcome variable. In the relationship between

GCV and PCI, GCVs included values of environmental con-

sumption, such as purchasing green or recyclable production

and reducing consumption environmental hazard. Therefore,

we assumed that PCI was influenced not only by biospheric

and environmental values but also by GCVs, mainly because

GCVs are more embedded in the consumption context than

are environmental values. Thus, we hypothesized the

following:

Hypothesis 1 (H1): GCVs will positively influence PCI.

Approach and Avoidance Motivation

When consumers face green products, in terms of decision

making, they need to judge their benefits and compare the

differences between expected and actual results. Consumers

with strong GCVs tend to consider the benefits that purchas-

ing products bring not only to themselves but also to the

environment. In the process of evaluation, such people tend

to make their choices toward a more environmentally friendly

result (owing to its importance for them) and avoid environ-

mentally hazardous results.

Furthermore, approaching happiness and avoiding pain is

the most important nature of human beings. Gray (1987) pro-

posed a behavioral motivation theory (Reinforcement

Sensitivity Theory [RST]), which describes the behavioral

approach system (BAS) and the behavioral inhibition system

(BIS). BAS refers to one’s sensitivity to rewards and positive

stimuli, activating behaviors that produce positive or plea-

surable goals, whereas BIS refers to one’s sensitivity to pun-

ishment cues and negative stimuli, inhibiting behaviors that

produce unpleasant outcomes to avoid them (Carver &

White, 1994; Merchán-Clavellino et al., 2019). Spielberg

et al. (2011) found that the activation approach (BAS, or

approach motivation) was associated with left-lateralized

middle frontal gyrus activation and that the region responds

to stimuli associated with expectations, harvests, and plea-

sure. Conversely, avoidance (BIS, or avoidance motivation)

was associated with right-lateralized middle frontal gyrus

activation and that the region responds to stimuli associated

with disappointment, loss, and pain. Therefore, BAS and BIS

are not related to the same part of the nervous system, mean-

ing that both systems could, potentially, be activated at the

same time.

Recently, these two concepts have been directly studied in

research areas such as emotion, sense of power, risk predic-

tions, sports psychology, and human experiences (Keltner

et al., 2003; Lochbaum & Gottardy, 2015; Updegraff et al.,

2004). These researches usually examine two aspects of

these two systems: (1) How to activate the BAS and BIS,

such as how Keltner et al. (2003), which suggested that high-

power perception activates the BAS; in another example,

Kramer and Yoon (2007) found that both positive and nega-

tive emotional information influenced individuals’ BAS. (2)

The factor which can be affected by the BAS and the BIS,

such as Carver and White (1994), which found that the BAS

can influence and evoke different emotions that makes con-

sumers have different emotional experiences in the con-

sumption process, which are affected by the BAS and the

BIS, findings that are supported by Arnold and Reynolds

(2012).

Moreover, BAS and BIS are closely related to consumer

behavior. Based on the regulatory focus theory (Higgins

et al., 2001), it was found that the BAS and the BIS could

govern how people pursue goals, and could be a chronic pre-

disposition of individuals or could be situational induced

(Aaker & Lee, 2001; Higgins et al., 2001). This finding

denotes that specific situations could activate the BAS and

the BIS. Arnold and Reynolds (2012) discussed the effect

mechanism of approach (BAS) and avoidance motivations

(BIS) on hedonic consumption in a retail setting, and found

that, as fundamental motivational dispositions, BAS and BIS

are cross-situational and could be positively related to

hedonic shopping motivations.

Generally speaking, BAS should be related positively to

PCI for several reasons. (a) Keltner et al. (2003) suggested

that high-power perception would activate the BAS; in the

4 SAGE Open

pro-environmental consumption setting, the consumer could

feel high-power perception by helping in the diminishment

of environmental degradation, thereby activating the BAS,

and the consumers’ environment improvement goal would

subsequently lead to PCI. (b) PCI can bring others’ moral

recognition and provide consumers with positive feedback

for their actions, which helps consumers to perceive the posi-

tive value brought by their behavior; these expectations that

the consumers have toward evoking positive reactions from

the environment by the prospect of a pro-environmental

behavior tend to activate the BAS, ultimately leading to the

PCI.

In the relationship between BIS and PCI, consumers may

come to feel powerlessness about environmental change,

which could evoke low-power perception, thereby activating

the BIS (Keltner et al., 2003); this may help consumers to

avoid behaviors that could produce further negative results

for the environment, leading them to act toward preventing

such occurrences; pro-environmental consumption behavior

is one of the ways to prevent negative results caused by envi-

ronmental changes, subsequently leading consumers to exert

their PCI. Thus, we hypothesized the following:

Hypothesis 2a (H2a): The BAS will positively influence

PCI.

Hypothesis 2b (H2b): The BIS will positively influence

PCI.

BAS and BIS, as fundamental motivation dispositions, are

influenced by cultural norms and values (Carver & White,

1994; Updegraff et al., 2004). Hence, in the pro-environmen-

tal consumption context, GCVs could be one of the important

influence factors that activate the BAS and the BIS. In other

words, consumers with stronger GCVs may more positively

perceive the purchase of green products (BAS activation/

approach motivation) and may help other consumers under-

stand the benefits of such products (BIS activation/avoidance

motivation), which promotes environmental protection and

pollution avoidance. The result of this series of psychological

mechanisms is the generation of pro-environmental con-

sumption behavior. Therefore, the BAS and the BIS can play

a mediating role between GCVs and PCI.

Hypothesis 3a (H3a): BAS will positively mediate the

relationship between GCVs and PCI.

Hypothesis 3b (H3b): BIS will positively mediate the

relationship between GCVs and PCI.

GI

GI refers to the outcome of the interaction between consum-

ers and green products. Anti et al. (1986) defined the concept

of involvement as a state of perceived importance or a state-

ment of one’s interest that was evoked by the stimulus and

the situation. Others have defined it somewhat differently:

Rothschild (1984) defined involvement as a statement of

one’s interest, motivation, or arousal, and subdivided the

concept into two categories, persistent involvement and situ-

ational involvement. Persistent involvement refers to con-

sumers’ persistent attention toward a product, whereas

situational involvement refers to consumers’ short attention

toward a product in a specific consumption situation.

Rothschild (1984) determined that involvement can have a

positive impact on consumers’ brand sensitivity: Consumers

with high involvement levels tend to more thoroughly search

for product information to compare and evaluate the product,

and consumers with low involvement tend to skip the infor-

mation searching process and go straight for the purchase. In

this study, we defined GI as a statement of interest, motiva-

tion, or arousal toward green products.

In the relationship between GCVs and PCI, consumers

with high GI will search for more information about green

products to compare and evaluate them—from functional

and valuable perspectives—to assist them in their purchas-

ing decisions. Consumers who have low GI will ignore

product information and only be affected by the product

advertisements. In a pro-environmental consumption con-

text, consumers with high GI would be able to evaluate the

environmental effect of their pro-environmental behavior,

which demonstrates that GI may be a mechanism influenc-

ing people’s GCVs, thereby making consumers with higher

GCVs more likely to display PCI. Therefore, GI may be a

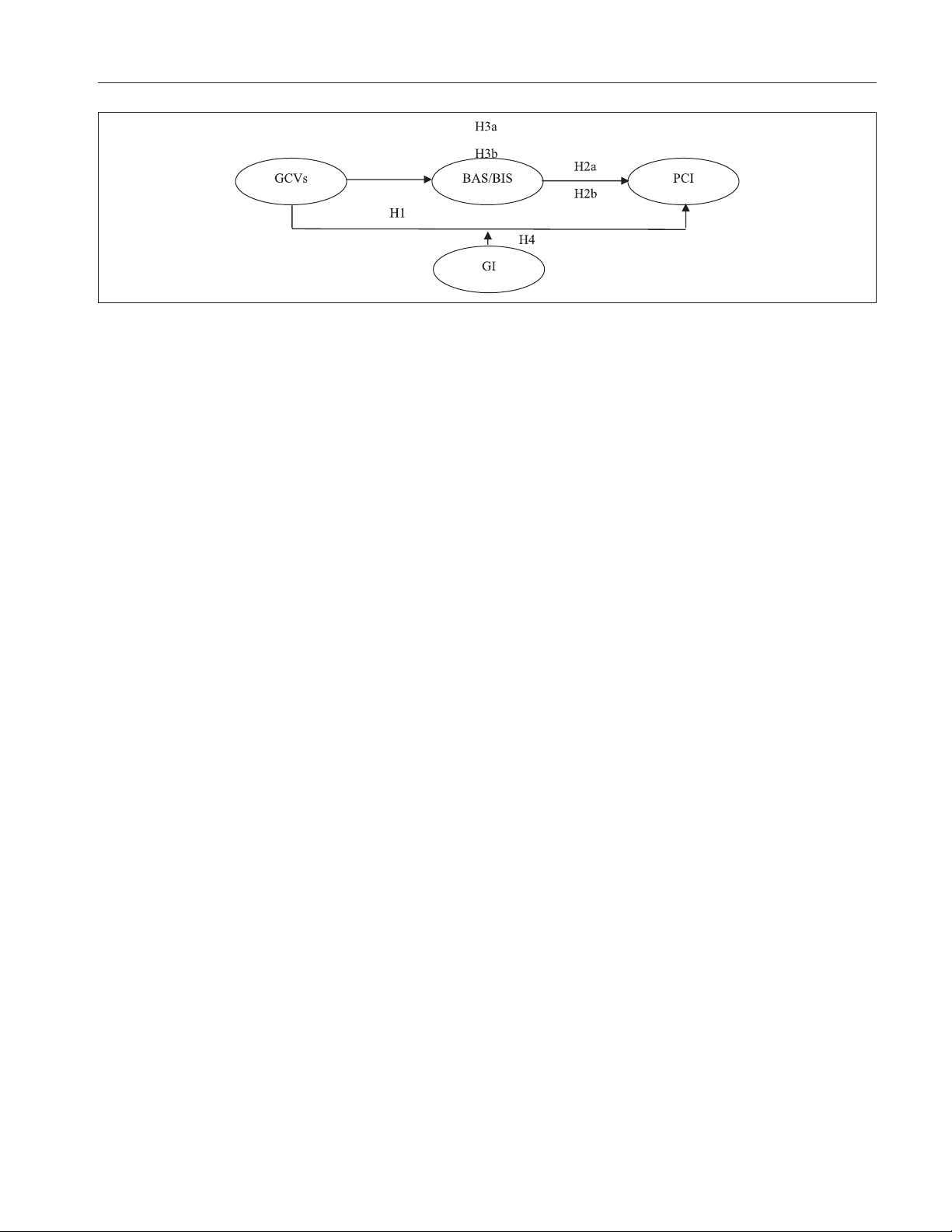

moderating variable between GCVs and PCI (see Figure 1).

Hypothesis 4 (H4): The positive relationship between

GCVs and PCI will be stronger when consumers’ GI is

high.

Method

Data Collection and Sample Description

Data were collected from actual shoppers in four urban

Chinese shopping streets—including Chongqing Road of

Changchun, Henan Street of Jilin, Taiyuan Street of

Shenyang, and Central Street of Harbin—through face-to-

face intercept surveys. Shoppers were randomly intercepted

and recruited to participate in this study. Data were collected

from 10:00 a.m. to 5:00 p.m. The face-to-face surveys were

administered by research assistants who were well trained

and instructed in intercepts and interviewing techniques.

Participants

Participants were assured that the collected data of this

research would be used exclusively for academic purposes.

Participants were asked to read a paragraph, including the

following content, before proceeding to the surveys:

Wang et al. 5

If you need to buy a refrigerator for your family, there are two

kinds of refrigerators you can choose, which are the energy-

efficient refrigerator and the ordinary refrigerator. Compared

with the conventional refrigerator, the energy-efficient

refrigerator is consistent in freezing and refrigeration, but has

better energy efficiency and a higher price.

Following Bentler and Chou’s (1987) and Hair et al.’s

(2014) suggestions, the sample sizes should be at least 15

times the number of the items in the measure of the observed

variables to ensure good statistical power of the study. In this

study, there were 34 items, so the minimum sample size

required was 510 samples, and 741 out of 1,000 intercepted

shoppers agreed to complete the survey questionnaire, result-

ing in a 74.1% response rate. Therefore, the statistical analy-

sis of this study had strong statistical power.

The demographic profile of these shoppers can be charac-

terized as follows: There were slightly more female partici-

pants (59.2%); approximately 62% of the participants were

aged between 18 and 25 years old; 26% were married and

74% were single; 74.4% had completed a university degree;

and all income ranges were well represented, as 21.9%

reported income between 12,000 and 15,000 Renminbi

(RMB), and 8.8% had an income greater than 80,000 RMB.

Measures

Scale structure and reliability analysis. The measurement scales

employed in this research were developed and validated in a

past study. For GCVs, we used a six-item scale adapted from

Haws et al.’s (2014) study. In this study, the Cronbach’s

alpha was .914. For the BAS and the BIS, we used 13 (BAS)

and seven items (BIS) that were adapted from Carver and

White’s (1994) study. In this study, the Cronbach’s alphas

were .915 and .769, respectively. The PCI scales used three

items adapted from Ajzen’s (1991) study, and GI scales used

five items adapted from Traylor and Joseph’s (1984) study.

In this study, the Cronbach’s alpha for the PCI scale was

.831, and the Cronbach’s alpha for the GI scale was .897. All

items were rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale, and all Cron-

bach’s alpha exceeded .700, exhibiting sufficient reliability.

Validity Analysis

Except for BIS (0.424), other constructs’ average variance

extracted were all above 0.500, and all constructs’ consis-

tency reliability were above 0.700. The chi-square value for

the confirmation factor analysis containing all research con-

struct measures was 2,493.831. Other goodness-of-fit mea-

sures were χ2/df = 6.704, non-normed fit index = 0.814,

comparative fit index = 0.837, and root mean square error of

approximation = 0.088.

We also followed Bollen and Stine’s (1992) model and

analyzed the model fit of this research. The Bollen-stine

bootstrap tests were 2,000 times; the results showed that the

χ2 was 515.49, χ2/df = 1.386, comparative fit index = 0.931,

non-normed fit index = 0.925, and root mean square error of

approximation = 0.023. We also chose five demographic

variables as control variables in this research (gender, age,

income, marital status, and education). Construct analyses

are shown in Table 1.

Intercorrelations among the variables are reported in

Table 2. The results indicated that GCVs were significantly

related to PCI (r = . 697, p < .001), BAS (r = .446, p <

.001) and BIS (r = .299, p < .001) were significantly related

to PCI, GCV was significantly related to BAS (r = .527. p <

.001), GCV was significantly related to BIS (r = .322,

p < .001), and GI was significantly related to PCI (r = . 632,

p < .001).

Results

Total and Indirect Effects

This study used the Partial Least Squares Structural Equation

Model (PLS-SEM) to test the hypotheses. By comparing

with the hierarchical linear regression model (e.g., ordinary

least squares [OLS]) and traditional structural equation

model (e.g., Analysis and Moment of Structure [AMOS]),

PLS-SEM relaxes the restrictions on normal distribution and

Figure 1. Theoretical research model.

Note. GCVs = green consumption values; BAS = behavioral approach system; BIS = behavioral inhibition system; PCI = pro-environmental consumption

intention; GI = green involvement.