Intrinsic disorder and coiled-coil formation in prostate

apoptosis response factor 4

David S. Libich

1,

*, Martin Schwalbe

1,

*, Sachin Kate

1

, Hariprasad Venugopal

1

, Jolyon K. Claridge

1

,

Patrick J. B. Edwards

1

, Kaushik Dutta

2

and Steven M. Pascal

1

1 Centre for Structural Biology, Institute of Fundamental Sciences and Department of Physics, Massey University, Palmerston North,

New Zealand

2 New York Structural Biology Centre, NY, USA

Introduction

Prostate apoptosis response factor-4 (Par-4) is an ubi-

quitously expressed and evolutionary conserved protein

that was initially identified as a pro-apoptotic factor in

rat AT-3 androgen-independent prostate cancer cells

exposed to ionomycin [1,2]. The identified pro-apopto-

tic and tumour-suppressive roles of Par-4 are consid-

ered to be its most important cellular functions and,

accordingly, Par-4 is downregulated in various cancers

[3]. The anti-cancer strategy employed by Par-4 is

achieved by direct activation of the cell-death machinery

(e.g. Fas ⁄FasL) [4] and inhibition of pro-survival fac-

tors (e.g. nuclear factor-kappa B) [5]. Furthermore,

ectopic over-expression of Par-4 can either directly

induce apoptosis or sensitize cancer cells to apoptotic

stimuli, dependent on cell type [6]. Primarily a cyto-

plasmic protein, translocation of Par-4 to the nucleus

is linked with the direct induction of apoptosis in

cancer cells [3,7,8]. Initially characterized in prostate

cancer, Par-4 has also been demonstrated to function

in renal cell carcinomas [9], leukaemia [10] and

Keywords

circular dichroism; coiled-coil; intrinsically

disordered protein; prostate apoptosis

response factor 4; solution NMR

spectroscopy

Correspondence

D. S. Libich or S. M. Pascal, Institute of

Fundamental Sciences, Massey University,

Turitea Site, Private Bag 11222, Palmerston

North 4442, New Zealand

Fax: +64 6 350 5682

Tel: +64 6 356 9099

E-mails: d.s.libich@massey.ac.nz;

s.pascal@massey.ac.nz

*These authors contributed equally to this

work

(Received 24 March 2009, accepted 6 May

2009)

doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07087.x

Prostate apoptosis response factor-4 (Par-4) is an ubiquitously expressed

pro-apoptotic and tumour suppressive protein that can both activate cell-

death mechanisms and inhibit pro-survival factors. Par-4 contains a highly

conserved coiled-coil region that serves as the primary recognition domain

for a large number of binding partners. Par-4 is also tightly regulated by

the aforementioned binding partners and by post-translational modifica-

tions. Biophysical data obtained in the present study indicate that Par-4

primarily comprises an intrinsically disordered protein. Bioinformatic

analysis of the highly conserved Par-4 reveals low sequence complexity and

enrichment in polar and charged amino acids. The high proteolytic suscep-

tibility and an increased hydrodynamic radius are consistent with a largely

extended structure in solution. Spectroscopic measurements using CD and

NMR also reveal characteristic features of intrinsic disorder. Under physio-

logical conditions, the data obtained show that Par-4 self-associates via the

C-terminal domain, forming a coiled-coil. Interruption of self-association

by urea also resulted in loss of secondary structure. These results are

consistent with the stabilization of the coiled-coil motif through an intra-

molecular association.

Abbreviations

CREB, cAMP-responsive element-binding protein; DLS, dynamic light scattering; GST, glutathione S-transferase; HSQC, heteronuclear single

quantum coherence; IDP, intrinsically disordered protein; IPTG, isopropyl thio-b-D-galactoside; LZ, leucine zipper; NLS, nuclear localization

sequence; Par-4, prostate apoptosis response factor 4; PK, protein kinase; SAC, selective apoptosis of cancer cells.

3710 FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 3710–3728 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS

neuroblastomas [11], as well as endometrial [12],

pancreatic [13] and gastric [8] cancers.

In addition to its role in cancer, Par-4 is thought to

assist in normal neuronal development by preventing

the hyper-proliferation of nerve tissues, in turn con-

trolling the number of neurones and glial cells in both

the peripheral and central nervous systems [14,15].

Par-4 is upregulated in several neurodegenerative dis-

eases, such as Alzheimer’s disease [16,17], Parkinson’s

disease [18], Huntington’s disease [19] and amyotrophic

lateral sclerosis [20]. Par-4 is also reportedly involved

in immune response modulation [21], synaptic function

modulation [22] and apoptosis of neurones that have

received a traumatic insult [23].

The C-terminal quarter of Par-4 (Fig. 1) is highly

conserved and shares some homology with the death

domains of other apoptotic proteins, such as Fas,

receptor-interacting protein, Fas-associated death

domain protein and tumour necrosis factor receptor-

associated death domain protein [24,25]. This region

functions as the primary recognition and binding site

for various partners of Par-4, including Wilms’ tumour

1 [7], Akt1 ⁄protein kinase (PK) B [26], atypical PKCs

(PKCs fand k⁄i) [24], p62 [27], death-associated pro-

tein-like ⁄zipper interacting kinase [28], THAP [29],

Amida [30], E2F1 [31], D

2

dopamine receptor [32],

b-site amyloid precursor protein cleaving enzyme 1

[17], apoptosis-antagonizing transcription factor [33]

and topoisomerase 1 [34]. In addition, several binding

partners have been shown to interact at various sites

N-terminal to the aforementioned C-terminal segment,

including the androgen receptor [35], F-actin [36],

14-3-3 [26] and the SPRY domain-containing suppressor

of cytokine signalling box proteins 1, 2 and 4 [37].

Par-4 contains several conserved phosphorylation

sites that are modified by kinases, such as PKA, PKC,

casein kinase II and Akt1, adding a further level of

regulation of the function of Par-4 [38]. Phosphoryla-

tion of an absolutely conserved threonine (rat T155,

human T163 or mouse T156; Fig. 1) by PKA is

required for nuclear translocation [8]. Phosphorylation

of a C-terminal serine residue (rat S249, human or

mouse S231; Fig. 1) by Akt1 effectively inactivates

Par-4 by allowing the chaperone protein 14-3-3 to bind

and sequester it in the cytoplasm, even if it is

phosphorylated on T155 [26].

These multiple interactions coupled with a high

degree of sequence conservation and post-translational

modification suggest that the in vivo role(s) of Par-4

are highly temporally and spatially regulated. Simi-

larly, the ubiquitous expression, post-translational

modifications and a plethora of binding partners are

characteristics common to many intrinsically disor-

dered proteins (IDPs) [39]. In the present study, we

demonstrate that residual structure exists in Par-4

because the measured hydrodynamic radius increased

under denaturing conditions, suggesting that the

ensemble becomes less compact. CD and NMR indi-

cate that Par-4 is primarily intrinsically disordered

under physiological conditions and exists as an ensem-

ble of fast-averaging (on the NMR time-scale) struc-

tures. Furthermore, Par-4 forms a stable coiled-coil

through a self-association event mediated by the C-ter-

minus. The coiled-coil was probed using increasing

concentrations of chaotropic agents and was found to

be very stable. Using NMR, the segment of Par-4 not

involved in the coiled-coil was shown to have spectral

features that were similar to those of a C-terminal

deletion mutant. This is important because it suggests

that Par-4 is able to bind more than one partner at a

time and thus could function as a hub linking the

functions of several proteins. The coiled-coil region of

Par-4 represents an important functional domain that

is an example of a gain of structure upon binding tran-

sition, which is another important feature of IDPs [40].

Results

All sequence numbering is made with reference to rat

Par-4, to reflect the recombinant rat (rrPar-4) constructs

used in these studies. Three constructs were created;

rrPar-4FL (Par-4 full-length, residues 1–332), rrPar-

4DLZ (deleted leucine zipper, residues 1–290) and rrPar-

4SAC [selective apoptosis of cancer cells (SAC) domain

construct, residues 137–195] (Fig. 2A). The sequence

identity expressed relative to rat Par-4 of mouse and

human is 92% and 76%, respectively, whereas African

clawed frog and zebra fish share 52% and 47%

sequence identity with rat, respectively (Fig. 1).

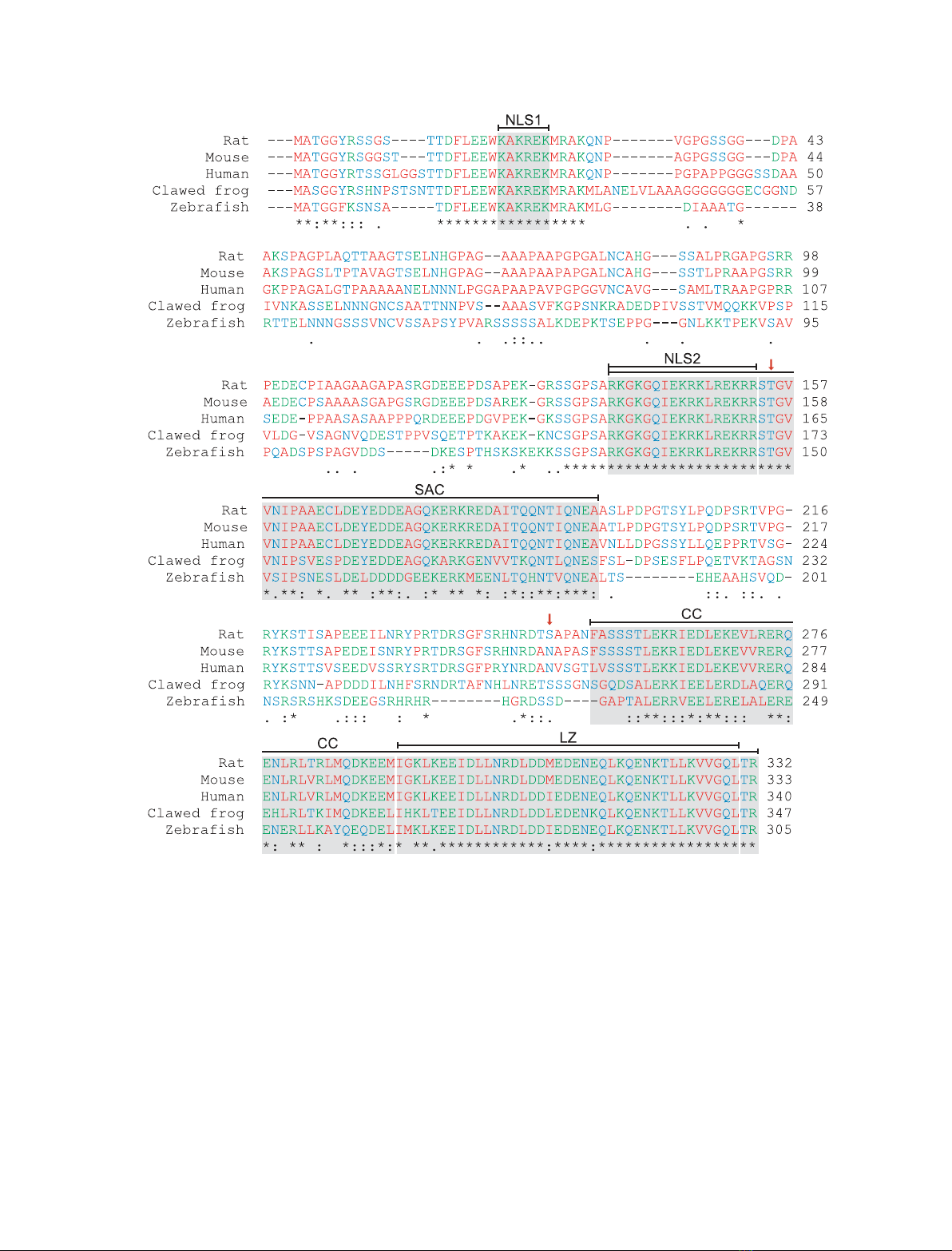

The nuclear localization sequences (NLS) 1 (residues

20–25) and 2 (residues 137–153) are strictly conserved

in all known Par-4 sequences (Fig. 1). The SAC

domain, which includes NLS2, is the minimum frag-

ment of Par-4 that is absolutely required for apoptosis

[6] and is completely conserved amongst mammals

(Fig. 1). Furthermore, there is a high degree of

sequence conservation in the C-terminal quarter of Par-

4, which contains primarily a coiled-coil-like sequence

(residues 254–332; Figs 1 and 2A). In particular, a leu-

cine zipper (residues 292–330), which is a subset of the

coiled-coil domain, is almost conserved in all known

Par-4 sequences, suggesting a common functionality

(Figs 1 and 2A). Relatively few Par-4 genes have been

sequenced. It has been suggested that the general pat-

tern of sequence conservation shown in Fig. 1 is likely

to be conserved across other mammalian sequences [1].

D. S. Libich et al. Intrinsic disorder in Par-4

FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 3710–3728 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS 3711

Based on disembl analysis [41], the majority (> 70%)

of Par-4 is predicted to be disordered. The putative

regions of order in Par-4, as indicated by grey bars in a

disembl plot (Fig. 2B), align with or occur within func-

tionally important regions of Par-4 (Fig. 2A), namely

NLS1, NLS2, SAC and the coiled-coil. Secondary

Fig. 1. Sequence alignment of the prostate apoptosis response factor 4 (Par-4). A BLASTP ⁄CLUSTALW [102,103] alignment of sequences of

Par-4 from various species: rat (Rattus norvegicus), mouse (Mus musculus), human (Homo sapiens), African clawed frog (Xenopus laevis)

and zebra fish (Danio rero). The amino acids are coloured: red (nonpolar side chains: G, A, V, L, I, M, P, F and W), blue (polar side chains: S,

T, N, Q, Y and C) and green (polar, charged side chains: K, R, H, D and E). Symbols: residues in that column are identical in all sequences

(*); substitutions are conservative (:); and substitutions are semi-conservative (.). The high degree of sequence conservation of Par-4

suggests functional significance and thus resistance to evolutionary pressure. With reference to the numbering of rat Par-4, several seg-

ments are of notable interest: two nuclear localization sequences [NLS1 (20–25) and 2 (137–153)], which are completely conserved among

all known Par-4s, and the SAC domain (137–195), which is defined by being the absolute minimum fragment required for apoptosis and

includes NLS2 [6]. The C-terminal domain (254–332) is a coiled-coil (CC) motif that encompasses a LZ (292–330) as a subset. Two important

phosphorylation sites, T155 and S249, are denoted by red arrows.

Intrinsic disorder in Par-4 D. S. Libich et al.

3712 FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 3710–3728 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS

structure prediction using gor4 [42] shows that the

regions with the highest helical propensity also occur in

the aforementioned regions and align with the disembl

predicted ordered regions (Fig. 2C). The hydrophobic

cluster analysis [43] of Fig. 2D indicates that the most

hydrophobic regions align with the putative ordered and

predicted helical regions.

A plot of mean net charge against mean hydropho-

bicity determined from a protein’s primary structure

may be used to classify it as folded or intrinsically dis-

ordered. Plot space is divided by an empirically deter-

mined line (

R¼2:785

H1:151) based on an analysis

by Uversky et al. [44]. The three constructs used in this

study are plotted in Fig. 3A along with several ‘classi-

cally folded’ proteins. Here, rrPar-4FL, rrPar-4DLZ

and rrPar-4SAC clearly fall into disordered space gen-

erally characterized by low mean hydrophobicity and

high net charge. The construct representing the SAC

domain (rrPar-4SAC), with 14 positively charged and

13 negatively charged residues but few hydrophobic

residues, lies further in the disordered region.

Figure 3B describes the sequence complexity of

rrPar-4FL by comparison with the percent difference

between the amino acid usage of a set of known IDPs

Fig. 2. (A) A block diagram of the three constructs of rrPar-4 used in the present study. Marked on each construct are the primary regions

of functional importance, including the nuclear localization sequences [NLS1 (20–25) and 2 (137–153), coloured green], the region necessary

for SAC (137–195), the coiled-coil C-terminal domain (CC, 254-332, coloured red) and the LZ (292–330, shown with hatching). The rrPar-

4DLZ construct lacks residues 291–332, which is approximately one-half of the coiled-coil and the entire leucine zipper. The rrPar-4SAC con-

struct represents residues 137–195 of Par-4, including NLS2. All three constructs used in the present study have an N-terminal GGS tag, a

remnant from the cleavage of the purification tag, which is omitted here for simplicity. (B) DISEMBL predicts regions of order ⁄disorder in pro-

teins using neural networks trained on multiple definitions of disorder [41]. The dashed line in (B) represents a threshold value separating

order and disorder. (C) Secondary structure (a-helix only shown) prediction using GOR4 [42] and (D) hydrophobic cluster analysis (HCA) [43], a

visually enhanced representation of the primary sequence that highlights clustering of hydrophobic residues using symbols ( ,T; ,S;¤,G;

w, P) and colours (red: P and acidic residues D, E, N, Q; blue: basic residues, H, K, R; green: hydrophobic residues, V, L, I, F, W, M, Y;

black: all other residues, G, S, T, C, A). The grey bars indicate the predicted regions of order in (B) and, for comparison, are extended over

(C) and (D).

D. S. Libich et al. Intrinsic disorder in Par-4

FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 3710–3728 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS 3713

versus a set of folded proteins (black bars). Positive

values indicate a depletion, whereas negative bars indi-

cate an enrichment relative to folded proteins. The pat-

tern of amino acid usage for rrPar-4FL (grey bars) is

in accordance with that generally observed for IDPs

[45,46], namely a depletion of order-promoting amino

acids (L, N, F, Y, I, W, C) and enrichment of dis-

order-promoting residues (S, Q, K, P, E). The amino

acid usage for rrPar-4DLZ and rrPar-4SAC follows a

similar pattern (not shown).

As calculated (i.e. from sequence) and experimen-

tally determined [i.e. from MS, Tricine-PAGE and

dynamic light scattering (DLS)], the molecular weights

for rrPar-4FL, rrPar-4DLZ and rrPar-4SAC are given

in Table 1. Because DLS measures the Stokes radius

(R

S

) of a particle, the equation log(R

S

) = 0.357 ·

log(MW) )0.204 was used to convert R

S

to MW for

comparative purposes [47,48]. Although this approxi-

mate calculation does not take into account the shape

of the particle (i.e. it assumes a sphere), the result is

useful for illustrating the degree of extended structure

in the protein.

The primary structure predicts MWs of 36.1, 31.1 and

7.0 kDa for rrPar-4FL, rrPar-4DLZ and rrPar-4SAC,

respectively. MALDI-TOF mass spectroscopy was used

to assess the purity and determine the sizes of the con-

structs produced. The sizes determined for rrPar-4DLZ

(44.5 Da difference between expected and observed) and

rrPar-4SAC (6.6 Da difference between expected and

observed after accounting for

15

N labelling of the sample

used for MS analysis) agree within error (approximately

0.1%) with the sizes predicted from sequence analysis

(Table 1). MS revealed that the rrPar-4FL construct is

approximately 0.2 kDa larger than expected.

Relative mobility analysis of the electrophoretic pro-

files of rrPar-4FL, rrPar-4DLZ and rrPar-4SAC using

a denaturing Tricine-PAGE system (see Experimental

procedures) determined apparent molecular weights of

49.1, 41.5 and 12.4 kDa, respectively. These sizes are

significantly larger (36%, 33% and 77% larger for

rrPar-4FL, rrPar-4DLZ and rrPar-4SAC, respectively)

than the expected MWs determined from the primary

structure or MS (Table 1).

The results of DLS experiments are shown in Table 2

and summarized in Table 1. The measured R

S

for

rrPar-4FL was 189 A

˚, which is much larger than

expected for a monomeric random coil, suggesting a

polymeric state for rrPar-4FL under these conditions.

Fig. 3. (A) Charge ⁄hydrophobicity plot of rrPar-4FL (335 residues),

rrPar-4DLZ (293 residues), and rrPar-4SAC (61 residues). The divid-

ing line

R¼2:785

H1:151 represents an empirically determined

divisor between intrinsically disordered (high charge, low hydropho-

bicity) and structured (low charge, high hydrophobicity) space.

Proteins such as aprotinin [104], actin [105], ubiquitin [106] and 3C

protease [107] are plotted as examples of classically folded

proteins. (B) Sequence complexity of rrPar-4FL (grey bars) com-

pared with the average amino acid distribution of IDPs (black bars)

relative to the average amino acid distribution of globular proteins.

The relative distributions were sampled from proteins (both IDPs

and folded) deposited in the Protein Data Bank. Positive and nega-

tive values indicate an enrichment or depletion, respectively, of a

particular residue relative to globular proteins. Residues marked

with an asterisk occur two-fold more or less frequently, on average,

in IDPs than in globular proteins [46].

Table 1. Hydrodynamic properties of rrPar-4 constructs using vari-

ous biophysical techniques. MW (kDa) and hydrodynamic radius (A

˚)

are shown in the format MW (R

S

) for three constructs using four

techniques. R

S

and MW were calculated from the primary structure

in reference to a folded conformation using log(R

S

) = 0.357 ·

log(MW) )0.204.

Construct Sequence

Method of analysis

MS PAGE DLS

rrPar-4FL 36.1 (26.5) 36.2 (26.5) 49.5 (29.6) 8899 (189)

rrPar-4-DLZ 31.1 (25.1) 31.2 (25.1) 41.5 (27.8) 64.1 (32.5)

rrPar-4 SAC 7.0 (14.8) 7.1 (14.8) 12.5 (18.1) 18.7 (20.9)

Intrinsic disorder in Par-4 D. S. Libich et al.

3714 FEBS Journal 276 (2009) 3710–3728 ª2009 The Authors Journal compilation ª2009 FEBS

![Vaccine và ứng dụng: Bài tiểu luận [chuẩn SEO]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2016/20160519/3008140018/135x160/652005293.jpg)