L-Lactate metabolism in potato tuber mitochondria

Gianluca Paventi, Roberto Pizzuto, Gabriella Chieppa and Salvatore Passarella

Dipartimento di Scienze per la Salute, Universita

`del Molise, Campobasso, Italy

According to the Davies–Roberts hypothesis, plants

primarily respond to oxygen limitation by a burst of

l-lactate production ([1] and refs there in). The acidifica-

tion of the cytoplasm during the first phase of anaerobi-

osis arising from lactic fermentation results in inhibition

of lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) and activation of

pyruvate decarboxylase [2]. As a result, a switch from

lactic to ethanolic fermentation occurs. In those organ-

isms that cannot switch to ethanolic fermentation, when

oxygen falls below 1%, glycolysis is stimulated and

l-lactate accumulates [3], leading to decreased cytoplasmic

pH and cell death [4,5]. Thus, according to the Davies–

Roberts concept, cytoplasmic acidification potentially

induces damage and death of intolerant plants.

Because of the damage that can arise from l-lactate

accumulation, a cellular safety valve to minimize that

damage is to be expected. It has been consistently repor-

ted that metabolism of l-lactate in potato after a period

of anoxia is accompanied by a two-fold increase in

LDH activity and by the induction of two LDH iso-

zymes [6]. These observations related to l-lactate meta-

bolism occurring in the cytoplasm involved pyruvate

formation via LDH, and further pyruvate metabolism,

both in mitochondria and in the cytoplasm. There is rea-

son to suspect, however, that mitochondria themselves

may be involved in l-lactate metabolism. This is based

on our previous work, which has shown that l-lactate is

transported into the organelles isolated from both rat

Keywords

L-lactate; L-lactate dehydrogenase;

mitochondrial transport; plant mitochondria;

shuttle

Correspondence

S. Passarella, Dipartimento di Scienze per la

Salute, Universita

`del Molise, Via De

Sanctis, 86100 Campobasso, Italy

Fax: +39 0 874 404778

Tel: +39 0 874 404868

E-mail: passarel@unimol.it

(Received 2 August 2006, revised 20

December 2006, accepted 10 January 2007)

doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.05687.x

We investigated the metabolism of l-lactate in mitochondria isolated from

potato tubers grown and saved after harvest in the absence of any chemical

agents. Immunologic analysis by western blot using goat polyclonal anti-

lactate dehydrogenase showed the existence of a mitochondrial lactate

dehydrogenase, the activity of which could be measured photometrically

only in mitochondria solubilized with Triton X-100. The addition of l-lac-

tate to potato tuber mitochondria caused: (a) a minor reduction of intra-

mitochondrial pyridine nucleotides, whose measured rate of change

increased in the presence of the inhibitor of the alternative oxidase salicyl

hydroxamic acid; (b) oxygen consumption not stimulated by ADP, but

inhibited by salicyl hydroxamic acid; and (c) activation of the alternative

oxidase as polarographically monitored in a manner prevented by oxamate,

an l-lactate dehydrogenase inhibitor. Potato tuber mitochondria were

shown to swell in isosmotic solutions of ammonium l-lactate in a stereo-

specific manner, thus showing that l-lactate enters mitochondria by a pro-

ton-compensated process. Externally added l-lactate caused the appearance

of pyruvate outside mitochondria, thus contributing to the oxidation of

extramitochondrial NADH. The rate of pyruvate efflux showed a sigmoidal

dependence on l-lactate concentration and was inhibited by phenylsucci-

nate. Hence, potato tuber mitochondria possess a non-energy-competent

l-lactate ⁄pyruvate shuttle. We maintain, therefore, that mitochondrial

metabolism of l-lactate plays a previously unsuspected role in the response

of potato to hypoxic stress.

Abbreviations

AOX, alternative oxidase; COX IV, subunit IV of cytochrome oxidase; FCCP, carbonyl cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy)-phenylhydrazone; LDH,

L-lactate dehydrogenase; PTM, potato tuber mitochondria; SHAM, salicyl hydroxamic acid.

FEBS Journal 274 (2007) 1459–1469 ª2007 The Authors Journal compilation ª2007 FEBS 1459

heart [7] and liver [8] and metabolized there. Moreover,

a major role for the mitochondrial LDHs in the transfer

of reducing equivalents from the cytosol to the respirat-

ory chain (lactate shuttle) was also proposed [7].

In order to ascertain whether and how energy meta-

bolism, and in particular l-lactate metabolism, can

change as a result of spontaneous hypoxia in plants,

we used potato, which is an important crop whose

tubers show a high sensitivity to O

2

deprivation [3].

We show here for the first time the existence of LDH

in isolated potato tuber mitochondria (PTM). This

enzyme is localized in the inner mitochondrial

compartments and uses NADP

+

as a cofactor, the

product, NADPH, being oxidized essentially by the

alternative oxidase (AOX), which is activated by pyru-

vate. The latter can also exit from the mitochondria in

a novel l-lactate ⁄pyruvate shuttle operating in a non-

energy-competent manner.

Results

The existence of LDH in mitochondria isolated

from potato tubers

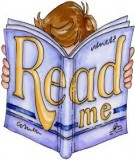

In order to verify the occurrence of LDH in PTM, use

was made of goat polyclonal antibodies raised against

LDH, which have already been shown to cross-react

with LDHs from different species [9–11]. Solubilized

mitochondrial proteins were analyzed by SDS ⁄PAGE,

blotted onto poly(vinylidene difluoride) membrane, and

then probed with the antibody to LDH. In agreement

with Hondred & Hanson [12], LDH protein was visual-

ized as a single band with a molecular mass of about

39 kDa. A typical experiment is reported in Fig. 1,

which shows clearly the presence of LDH in the

mitochondrial fraction. Confirmation of this site of ori-

gin was provided by use of a specific antibody against

subunit IV of the cytochrome coxidase (COX IV). A

band corresponding to a protein of molecular mass

35 kDa was observed; this is likely to arise from an

aggregate of COX IV (13 kDa [13]) and other unidenti-

fied protein ⁄s, as already shown in pea mitochondria

[14]. The occurrence of respirasomes in potato mito-

chondria has been recently reported [15], making poss-

ible the occurrence of aggregates not separated in the

SDS ⁄PAGE procedure. Whatever its origins, the lack

of this band in the cytosolic fraction showed that the

35 kDa band is specific for PTM and not a technical

artefact. In the same experiment, it was shown that the

PTM fraction did not contain b-tubulin, a protein

restricted to the cytoplasm, thus ruling out the possibil-

ity that the LDH detected arose from cytosolic contam-

ination. Contamination by other particulate ⁄membrane

fractions was also ruled out, as we used purified mito-

chondria free of subcellular contamination (see Experi-

mental procedures).

The cytosolic fraction was free of mitochondrial

COX IV, showing that minimal rupture of PTM had

occurred during isolation. The intactness of the mit-

ochondrial outer membrane was measured as in Douce

et al. [16], and found to be 95%. In addition, we found

negligible fumarase activity, a plant mitochondrial

marker [17], in suspensions of mitochondria, thus fur-

ther confirming the intactness of the inner membrane.

To establish where LDH is localized within the

mitochondria and whether it is active, LDH was

assayed photometrically by measuring the absorbance

decrease of NADH [18] in the presence of pyruvate in

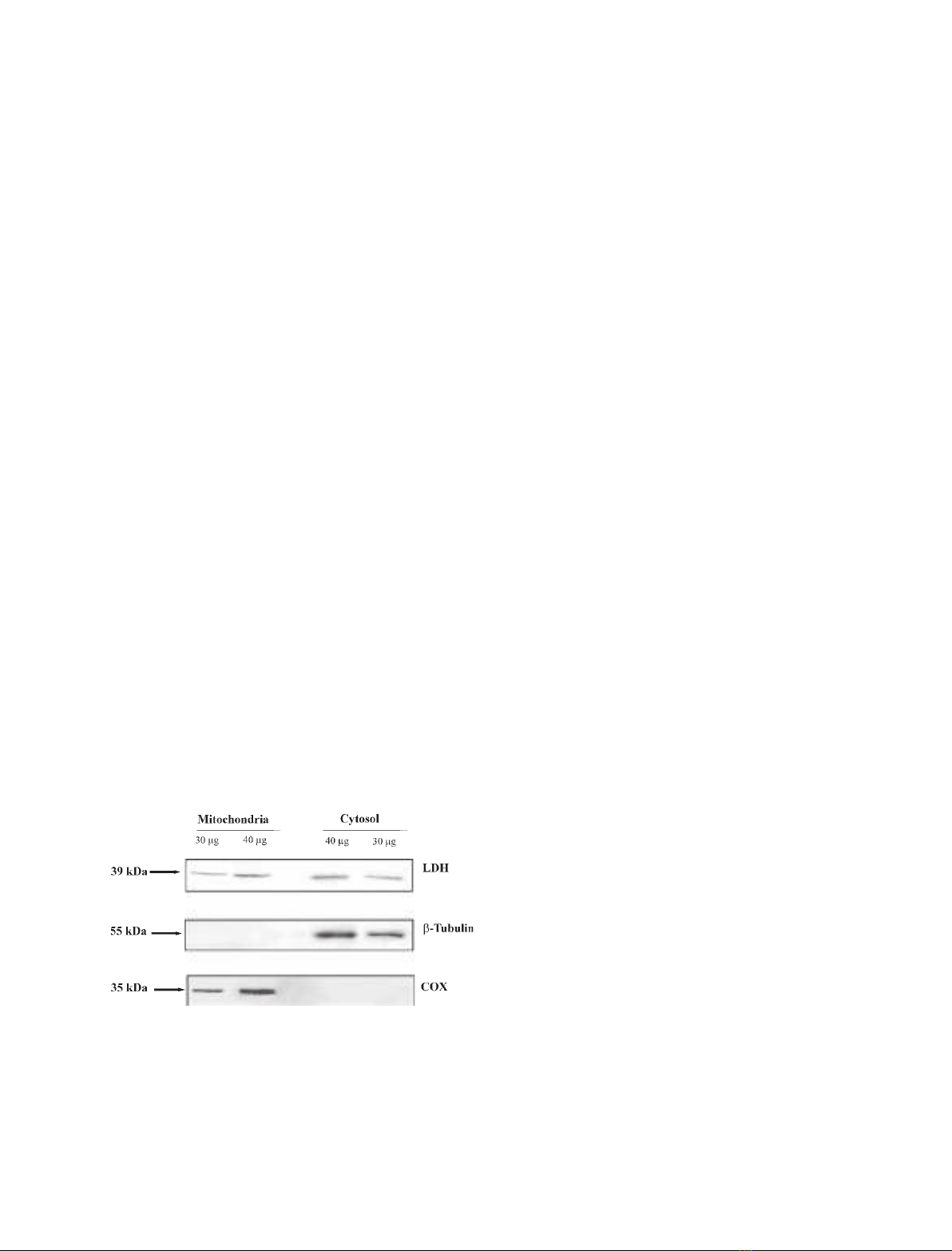

isolated PTM. When PTM (0.1 mg protein) were incu-

bated in the presence of NADH (0.2 mm), oxidation

occurred, catalyzed by external NADPH dehydro-

genases (Fig. 2A). The constant rate of decrease

in absorbance (about 130 nmolÆmin

)1

Æmg protein)

remained unchanged when pyruvate (10 mm) was

added; that is, the LDH was not accessible to sub-

strates. Consistently, no NADH formation was found

in the presence of 10 mml-lactate (not shown).

In order to rule out the possibility that l-lactate is

oxidized on the external face of the inner membrane,

with electrons transferred to the inner surface, intact

PTM were assayed for LDH activity by using phena-

zine methosulfate and dichloroindophenol (Fig. 2B), as

in Atlante et al. [19]. A negligible decrease in dichloro-

indophenol absorbance at 600 nm was found when

l-lactate (10 mm) was added to the PTM, either in the

absence or in the presence of 1 mmNAD

+

, confirming

the absence of LDH activity in the outer membrane, in

Fig. 1. Immunodetection of mitochondrial LDH. Solubilized protein

(30 and 40 lg) from both mitochondrial and cytosolic fractions was

analyzed by western blot as described in Experimental procedures.

Membrane blots were incubated with polyclonal anti-LDH, anti-

COX IV and anti-b-tubulin. COX IV and b-tubulin were used as mit-

ochondrial and cytosolic markers, respectively.

L-Lactate metabolism in PTM G. Paventi et al.

1460 FEBS Journal 274 (2007) 1459–1469 ª2007 The Authors Journal compilation ª2007 FEBS

the intermembrane space or on the outer side of the

mitochondrial inner membrane, or in any contamin-

ation of the mitochondrial suspension. Addition of

LDH externally produced a rapid decrease in absorp-

tion by dichloroindophenol. To validate the experi-

mental protocol that we had used, we confirmed that

addition of 0.3 mmglycerol 3-phosphate to PTM in

the presence of phenazine methosulfate and dichloroin-

dophenol resulted in a decrease of dichloroindophenol

absorbance with a rate of about 22 nmolÆmin

)1

Æmg

)1

protein, arising from the activity of glycerol 3-phos-

phate dehydrogenase (EC 1.1.1.8), which is located on

the outer side of the mitochondrial inner membrane

(Fig. 2B,a). On the other hand, no oxidation of succi-

nate by succinate dehydrogenase (which is located on

the matrix side of the inner mitochondrial membrane)

occurred with intact PTM. Oxidation did occur after

the addition of 0.1% Triton X-100, which solubilized

the mitochondrial membranes and allowed the interac-

tion between dichloroindophenol and the succinate

dehydrogenase complex (Fig. 2B,b).

To confirm that LDH is located in the internal mit-

ochondrial compartments, i.e. in the inner face of the

mitochondrial membrane or in the matrix, PTM were

solubilized with Triton X-100 (0.2%). Added NADH

(0.2 mm) was oxidized at a rate of about 105 nmolÆ

min

)1

Æmg

)1

protein, but when pyruvate was added, this

rate increased to about 170 nmolÆmin

)1

Æmg

)1

protein

(Fig. 2C), showing that LDH is present in the inner

mitochondrial compartments.

The kinetic characteristics of the LDH reaction were

studied by determining the dependence of the rate of

oxidation of NADH on increasing concentrations of

externally added pyruvate in solubilized mitochondria

Fig. 2. Mitochondrial LDH activity assay in

PTM. (A) PTM (0.1 mg) were incubated in

2 mL of the standard medium (see Experi-

mental procedures) containing 200 lM

NADH, and the absorbance (A

340

) was con-

tinuously monitored. Pyruvate (PYR, 10 mM)

was added at the time indicated by the

arrow. The numbers alongside the traces

refer to the rate of oxidation of NADH in

nmolÆmin

)1

Æmg

)1

protein. (B) PTM (0.2 mg)

were incubated in 2 mL of standard medium

in the presence of phenazine methosulfate

(PMS) (30 lM) plus dichloroindophenol

(50 lM), either in the presence or in the

absence of NAD

+

, and the absorbance

(A

600

) was continuously monitored. At the

times indicated by the arrows, L-lactate

(L-LAC, 10 mM) and LDH (0.1 eu) were

added. The insets show control experi-

ments: at the times indicated by the arrows,

glycerol 3-phosphate (G3P, 0.3 mM) (a) and

succinate (SUCC, 5 mM) and Triton X-100

(0.2%) (b) were added to mitochondria trea-

ted with phenazine methosulfate and dichlo-

roindophenol. Numbers along the curves are

rates of L-lactate, succinate or glycerol

3-phosphate oxidation expressed as nmol

dichloroindophenol reducedÆmin

)1

Æmg

)1

pro-

tein. (C) PTM solubilized with Triton X-100

(0.2%) were incubated in 2 mL of the stand-

ard medium, containing 200 lMNADH, and

the absorbance (A

340

) was continuously

monitored. Pyruvate (1.5 mM) was added at

the time indicated by the arrow. The num-

bers alongside the traces refer to the rate of

oxidation of NADH in nmolÆmin

)1

Æmg

)1

protein.

G. Paventi et al.L-Lactate metabolism in PTM

FEBS Journal 274 (2007) 1459–1469 ª2007 The Authors Journal compilation ª2007 FEBS 1461

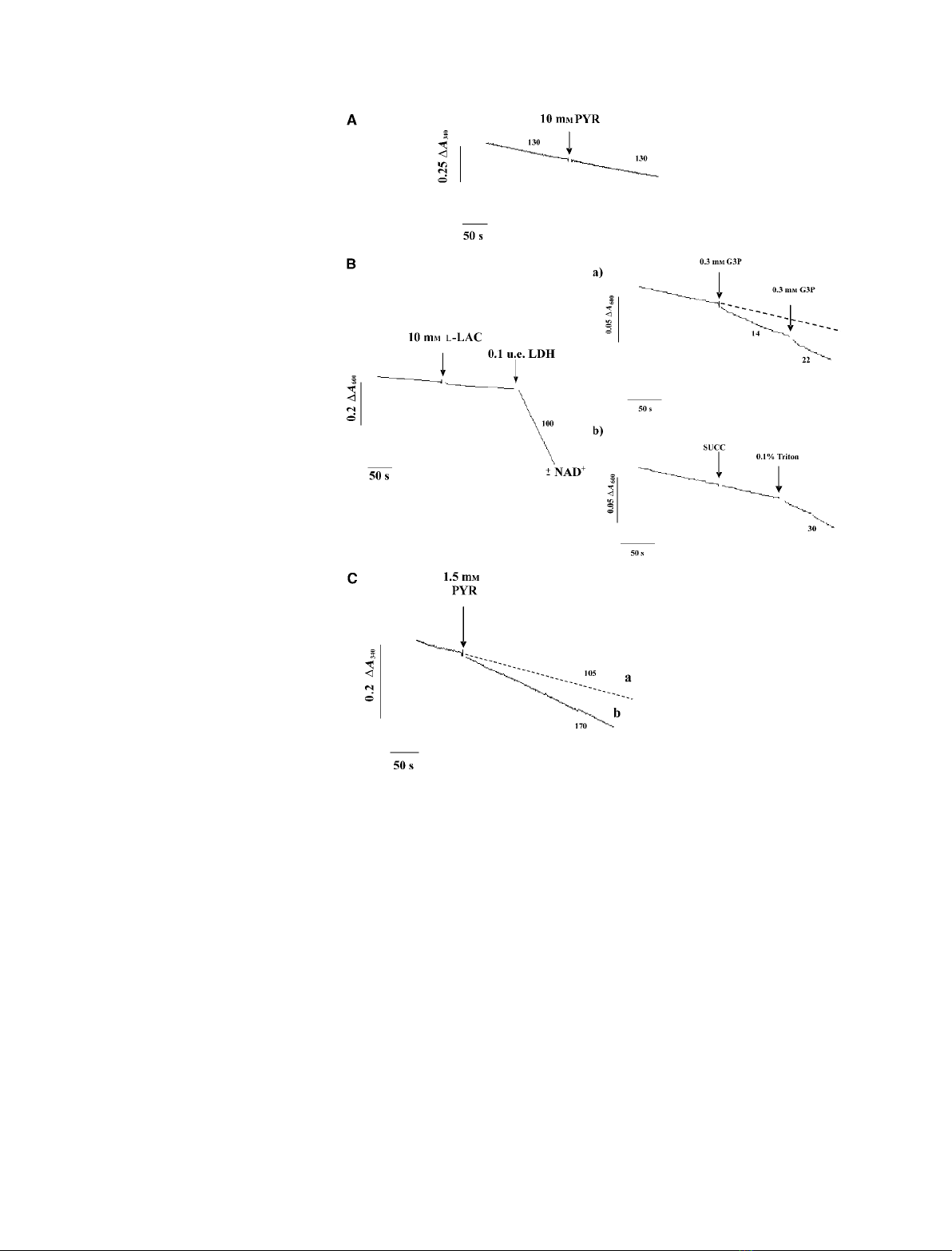

(Fig. 3). Saturation kinetics were found with a K

m

value

of 0.63 ± 0.14 mm; the V

max

value was 85 ± 7 nmolÆ

min

)1

Æmg

)1

sample protein.

Unfortunately, spontaneous oxidation of the NADH

formed during the oxidation of l-lactate prevented

assay with l-lactate and NAD

+

as the substrate pair.

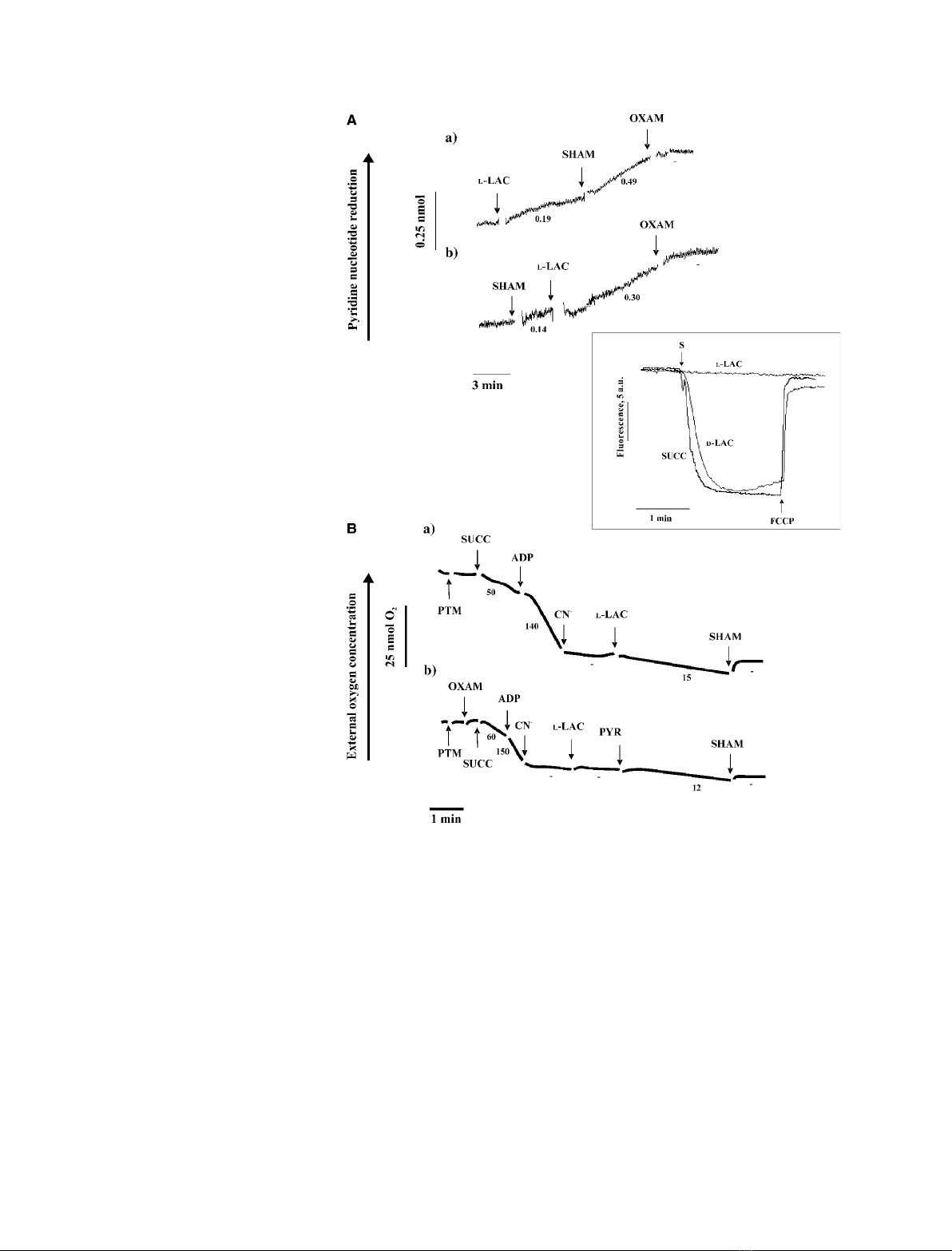

L-Lactate metabolism in mitochondria

Uptake and metabolism of l-lactate was further inves-

tigated in a set of experiments carried out with isolated

coupled PTM. The assumption here is that the mitoch-

ondrial LDH is devoted to oxidation of l-lactate

rather than reduction of pyruvate, as the latter would

be immediately oxidized by the pyruvate dehydroge-

nase complex (K

m

¼0.06 mm[20]). l-Lactate metabo-

lism was monitored by determining the ability of

externally added l-lactate to reduce intramitochondrial

dehydrogenase cofactors. In this case, we resorted to

fluorimetric techniques that have previously been used

to monitor changes in the redox state of pyridine nu-

cleotides [21]. Reduction of mitochondrial NAD(P)

+

was found to occur at a rate of 0.19 nmolÆmin

)1

Æmg

)1

protein when l-lactate was added to PTM previously

incubated with or without the uncoupler carbonyl

cyanide p-(trifluoromethoxy)-phenylhydrazone (FCCP)

and then treated with cyanide (CN

–

) (not shown). The

observed rate of reduction was, however, likely to be

underestimated, as the newly formed NAD(P)H would

be rapidly oxidized by the mitochondrial AOX, which

is usually activated by pyruvate, the product of l-lac-

tate metabolism. Hence, we checked whether inhibition

of AOX would cause an increase in the measured rate

of pyridine nucleotide reduction. To achieve this, use

was made of salicyl hydroxamic acid (SHAM, 1 mm),

an AOX inhibitor [22]. Addition of SHAM resulted in

a 150% increase in the measured rate of NAD(P)H

formation (Fig. 4A,a). Consistently, addition of l-lac-

tate to PTM previously incubated with SHAM caused

an increase in the rate of NAD(P)H formation

(Fig. 4A,b). In both cases, the addition of oxamate

(10 mm), an inhibitor of LDHs [23], completely

blocked the increase in fluorescence.

The failure of NADH, newly synthesized during

l-lactate oxidation, to be oxidized in the cytochrome

pathways was confirmed in another experiment (inset

to Fig. 4), in which we checked whether addition of

l-lactate to PTM could produce an increase in the

membrane potential as measured by using safranine O

as a fluorimetric probe. In contrast to succinate

(5 mm) and d-lactate (10 mm), l-lactate (10 mm) failed

to generate a change in electrical membrane potential,

DY. As expected, externally added FCCP (1 lm)

caused membrane potential collapse.

In the same experiment, we investigated, as in

Pastore et al. [24], whether l-lactate itself could activate

AOX, and obtained the results shown in Fig. 4B. In

this case, succinate was added to the mitochondria, fol-

lowed by ADP. Oxygen consumption via the electron

transfer chain was then blocked with CN

–

, and finally

l-lactate was added either in the absence (a) or presence

(b) of oxamate. In the former case, oxygen consump-

tion was restored, but in the latter, l-lactate addition

failed to restore oxygen uptake, thus showing that

l-lactate itself was not responsible for AOX activation.

It is likely that in the absence of oxamate, activation of

AOX was due to the newly formed pyruvate. In a par-

allel experiment, the ability of l-lactate to cause oxygen

uptake by PTM was investigated. We found that addi-

tion of 10 mml-lactate resulted in oxygen uptake at a

rate of 20 nmol O

2

Æmin

)1

Æmg

)1

protein. As expected,

this uptake was not stimulated by 0.2 mmADP, and

was completely prevented following addition of SHAM

(not shown). Control experiments showed that SHAM

did not affect O

2

uptake due to either NADH or succi-

nate in the absence of CN

–

(not shown).

L-Lactate transport in PTM

The experiments reported above raise the question of

how l-lactate produced in the cytosol can cross the

mitochondrial membrane. To gain insight into this,

swelling experiments were carried out as in de Bari

et al. [25]; the results are shown in Fig. 5. PTM

Fig. 3. Assay of LDH activity in PTM solubilized with Triton X-100.

Pyruvate was added at the indicated concentrations to PTM treated

with Triton X-100 (0.2%). The rates (v

o

) of NADH oxidation, calcula-

ted as difference of rate in traces (b) and (a) of Fig. 2C, are

expressed as nmol pyruvate reducedÆmin

)1

Æmg

)1

protein.

L-Lactate metabolism in PTM G. Paventi et al.

1462 FEBS Journal 274 (2007) 1459–1469 ª2007 The Authors Journal compilation ª2007 FEBS

suspended in 0.18 mammonium l-lactate showed

spontaneous swelling, but with a rate and to an extent

significantly lower than those found with ammonium

d-lactate, as judged by statistical analysis of five swell-

ing experiments using Student’s t-test (P<0.02). This

shows that both d-lactate and l-lactate can enter

PTM, but that the uptake is stereospecific. The results

indicate that l-lactate enters mitochondria in a proton-

compensated manner. The metabolite transport para-

digm proposed in Passarella et al. [21] suggests that

net carbon uptake by mitochondria is accompanied by

efflux of newly synthesized compound ⁄s. We wished to

determine whether this applies in the case of l-lactate.

In particular, in the light of the occurrence of an l-lac-

tate ⁄pyruvate shuttle in mammalian mitochondria, the

possible efflux of pyruvate as a result of l-lactate addi-

tion to PTM was investigated (Fig. 6A). The concen-

tration of pyruvate outside PTM was negligible, as

shown by the minimal change in absorbance at

334 nm found when commercial LDH was added

along with the NADH to complete the pyruvate-

detecting system (for details, see Experimental proce-

dures). On the other hand, in the presence of l-lactate

(10 mm), the absorbance at 334 nm decreased rapidly,

which is indicative of the appearance of pyruvate in

the extramitochondrial phase. This can be explained

on the basis that the l-lactate imported into the mito-

chondria forms pyruvate via the mitochondrial LDH,

Fig. 4. Effect of L-lactate addition to PTM.

Change in the redox state of pyridine nucle-

otides (A), failure to cause membrane poten-

tial generation (inset), and activation of AOX

(B). (A) PTM (0.2 mg protein) were incuba-

ted in 2 mL of the standard medium (see

Experimental procedures), and the fluores-

cence (k

ex

334 nm, k

em

456 nm) was con-

tinuously monitored. At the times indicated

by the arrows, L-lactate (10 mm), SHAM

(1 mM), and oxamate (OXAM, 10 mM) were

added. The numbers alongside the traces

refer to the rate of reduction of NAD(P)

+

in

nmolÆmin

)1

Æmg

)1

protein. Inset: PTM

(0.2 mg of protein) were incubated in 2 mL

of the standard medium in the presence of

2.5 lMsafranin, and fluorescence

(k

ex

520 nm, k

em

570 nm), measured as

arbitrary units (a.u.), was continuously

monitored. Where indicated by S, L-lactate

(L-LAC, 10 mM), D-lactate (D-LAC, 10 mM)or

succinate (5 mM) were added separately;

where indicated, FCCP (1 lM) was added.

(B) PTM (0.2 mg protein) were suspended

at 25 C in 1 mL of respiratory medium, and

the amount of residual oxygen was meas-

ured as a function of time. Where indicated,

the following additions were made: succi-

nate (SUCC, 5 mM), oxamate (10 mM), ADP

(0.2 mM), cyanide (CN

–

,1mM), L-lactate

(L-LAC, 10 mM), pyruvate (PYR, 5 mM), and

SHAM (1 mM). Numbers along the curves

are rates of oxygen uptake expressed as

nmol O

2

Æmin

)1

Æmg

)1

mitochondrial protein.

G. Paventi et al.L-Lactate metabolism in PTM

FEBS Journal 274 (2007) 1459–1469 ª2007 The Authors Journal compilation ª2007 FEBS 1463