An extension to the metabolic control theory taking into account

correlations between enzyme concentrations

Se

´bastien Lion

1,

*, Fre

´de

´ric Gabriel

1

, Bruno Bost

2

, Julie Fie

´vet

1

, Christine Dillmann

1

and

Dominique de Vienne

1

1

UMR de Ge

´ne

´tique Ve

´ge

´tale, INRA/UPS/CNRS/INAPG, Ferme du Moulon, Gif-sur-Yvette, France;

2

Institut de Ge

´ne

´tique et

Microbiologie, CNRS UMR 8621, Universite

´Paris Sud, Orsay Cedex, France

The classical metabolic control theory [Kacser, H. &

Burns, J.A. (1973) Symp.Soc.Exp.Biol.27, 65–104;

Heinrich, R. & Rapoport, T. (1974) Eur. J. Biochem. 42,

89–95.] does not take into account experimental evidence

for correlations between enzyme concentrations in the

cell. We investigated the implications of two causes of

linear correlations: competition between enzymes, which

is a mere physical adaptation of the cell to the limitation

of resources and space, and regulatory correlations,

which result from the existence of regulatory networks.

These correlations generate redistribution of enzyme

concentrations when the concentration of an enzyme

varies; this may dramatically alter the flux and metabolite

concentration curves. In particular, negative correlations

cause the flux to have a maximum value for a defined

distribution of enzyme concentrations. Redistribution

coefficients of enzyme concentrations allowed us to cal-

culate the Ôcombined response coefficientÕthat quantifies

the response of flux or metabolite concentration to a

perturbation of enzyme concentration.

Keywords: biochemical modelling; cellular constraint; flux;

metabolite; response coefficient.

The introduction of the metabolic control theory by Kacser

& Burns [1] and Heinrich & Rapoport [2] was a great

improvement in our understanding of the control of

metabolism (for a review see [3]). Numerous extensions to

the classical theory have been proposed to get rid of some

restrictive hypotheses of the initial theory. Extensions exist,

for example, for nonproportionality of the rates of reaction

to enzyme concentration [4], enzyme–enzyme interaction

[5,6], time-varying systems [7,8], or supply–demand analysis

[9]. Nevertheless, most studies have neglected the correla-

tions that exist between enzyme amounts in the cell.

Concentration is a key parameter for enzyme activity.

Changes in expression of enzyme genes play a central role in

the physiology of the cell, and dramatic modifications of the

cell proteome are consistently observed over development

and differentiation, or in response to environmental changes

(see http://us.expasy.org for examples in various species). In

addition, genetic studies have revealed natural variability for

enzyme concentration, for instance for alcohol dehydro-

genase in Drosophila [10] or lactate dehydrogenase in

Fundulus heteroclitus [11]. Other examples can also be

found [12,13]. Quantitative proteomic approaches have

confirmed that a majority of proteins/enzymes can display

a large range of variation within species [14–19]. Those

physiological or genetic variations are expected to be

interdependent. There is evidence for cellular constraints

that induce a variation of concentration of some enzymes

in response to a variation of others. These correlations

between enzyme concentrations undoubtedly have an

impact on the behaviour of metabolic systems, and hence

on their evolution. Two kinds of correlations will be studied

in this paper. The first one will be referred to as competition.

It is a mere physical adaptation of the cell to energetic or

steric constraints. The second one results from regulatory

networks. It will be referred to as regulation.

Competitive constraints on the variation of enzyme

concentrations have already been pointed out. Such

constraints have the effect of avoiding macromolecular

crowding, which can result in a modification of catalytic

and/or thermodynamic properties of enzymes [20], in a

limitation of solubility leading to partial protein crystalliza-

tion or aggregation [21,22], or a decrease in the diffusion of

essential metabolites ([23], for a review see [24]). Other

arguments include the limitation of resources, the energetic

cost of maintaining the cellular concentrations of enzymes

[25–27], and the availability of amino acids or elements of

the transcription and translation machinery, which has been

shown to be a limiting factor of protein synthesis in

Escherichia coli [28] and Saccharomyces cerevisiae [29].

Kacser & Beeby [30] were among the first to suggest that

the hyperbolic flux–activity relationship must ultimately

decline, for no more profound reason than that the cell or

organism must eventually reach a point at which the cost of

producing excess enzyme outweighs the benefit in fitness

that can be derived from possessing the excess [31,32].

It is clear that such competitive constraints imply that

variations of enzyme concentrations are negatively correla-

ted: an increase in the concentration of some enzymes

Correspondence to D. de Vienne, UMR de Ge

´ne

´tique Ve

´ge

´tale,

INRA/UPS/CNRS/INAPG, Ferme du Moulon, 91190 Gif-sur-

Yvette, France. Fax: +33 1 69 33 23 40, Tel.: +33 1 69 33 23 60,

E-mail: devienne@moulon.inra.fr

*Present address: Laboratoire d’e

´cologie, E

´cole normale supe

´rieure,

46, rue d’Ulm, 75005 Paris, France.

(Received 19 July 2004, revised 20 September 2004,

accepted 22 September 2004)

Eur. J. Biochem. 271, 4375–4391 (2004) FEBS 2004 doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.2004.04375.x

causes a decrease in the concentration of other enzymes,

which can lead to important metabolic perturbations, i.e.

to the so-called protein burden effect [33]. For instance,

overexpression of b-galactosidase in E. coli was found to

reduce the synthesis of the other proteins [34] and over-

expression of glycolysis enzymes in Zymomonas mobilis has

been shown to reduce glycolytic flux [35]: therefore, for large

enzyme concentrations, the classical hyperbolic shape of the

flux curve, as predicted by the metabolic control theory,

does not describe in a satisfactory way the behaviour of the

metabolic pathway. Flux can be expected to decrease when

enzyme concentration becomes too high, and it may be

interesting to model such behaviour.

Regulatory correlations can be positive or negative. The

production and degradation of enzymes, which determines

their concentration, is related to the structure of the genetic

regulatory network [36]. The lactose operon in E. coli [37] is

a well known example of a regulatory system that induces

correlations between the concentrations of the enzymes

involved in lactose metabolism. Several experimental and

theoretical studies have been devoted to the understanding

of the mechanisms of regulatory networks [38–41]. Meta-

bolic engineering makes an important use of regulation of

metabolic pathways to achieve overexpression of the

products of interest. For instance, Prati et al. [42] reported

a way to achieve simultaneous inhibition and activation of

two glycosyltransferases of the O-glycosylation pathway in

Chinese hamster ovary cells. In Lactococcus lactis, several

genes of glycolysis have been shown to be expressed at

higher levels on glucose than on galactose [43]. The authors

interpreted this as a result of two different regulatory

networks. With the growing use of quantitative proteomics

methods, we can expect to find many more examples of

correlations between enzymes, even if we still lack the tools

to determine whether regulatory networks actually underlie

these correlations.

The existence of these competitive and regulatory corre-

lations between enzymes is assumed to constrain the

response of the metabolic systems. Here, we present an

extension of the metabolic control theory in which response

coefficients allow us to quantify the change of a metabolic

variable (flux or metabolite concentration) in response to a

perturbation of a parameter (enzyme concentration) and to

the variations of other parameters resulting from that

perturbation. We apply the general concept of a Ôcombined

response coefficientÕto a linear model of redistribution of

enzyme concentrations in order to study the systemic

consequences of enzyme correlations.

Control of metabolic pathways and

redistribution of enzyme concentrations

Control of metabolic variables

Let us consider a metabolic pathway with nenzymes

E

1

,E

2

,…,E

n

catalyzing reversible reactions between sub-

strates S

1

,…,S

m

(mmetabolites).

To quantify the response of a systemic variable y,suchas

the flux in the pathway or the concentration of a metabolite, to

an infinitesimal change in the activity (concentration) of

enzyme E

k

, Kacser & Burns [1] and Heinrich & Rapoport [2]

introduced the control coefficient. In the revised nomen-

clature for metabolic control analysis, the control coefficient

Cy

kis defined as the steady-state response in yto a change in

the local rate of step k,v

k

, with no reference to enzyme con-

centration (http://www.sun.ac.za/biochem/mcanom.html).

In particular, the control coefficient of flux Jwith respect

to step kis:

CJ

k¼vk

J

@J

@vk

and the control coefficient of metabolite concentration S

i

with respect to step kis:

CSi

k¼vk

Si

@Si

@vk

Summation theorems can be derived for metabolite and

flux control coefficients. Summing over all reactions, we

have [1]:

X

n

j¼1

CJ

j¼1and X

n

j¼1

CSi

j¼0

These relationships show that the control of flux (or

metabolite concentration) is shared among all enzymes in

the pathway.

Control coefficients are systemic properties. We can also

define local properties such as the elasticity, which quantifies

theeffectofanyparameterpthat affects the local rate of an

individual (isolated) step. The elasticity coefficient e

k

p

for

step kis written as [1]:

ek

p¼p

vk

@vk

@p

Introducing correlations between enzyme concentrations

The classical form of metabolic control theory implicitly

considers that enzyme concentration can increase towards

infinity, which is biologically inconsistent. Competitive and

regulatory constraints on enzyme concentrations exist, that

can be described with a model of redistribution of enzyme

concentrations.

Weconsideredasystemstartinginastatedefinedbythe

concentrations

E0¼ðE01 ;E02; :::; E0k; :::; E0nÞ

of the nenzymes, and supposed that a variation of the

concentration of a target enzyme E

k

results in a variation of

the concentrations of other enzymes.

Redistribution coefficient. In order to quantify the impact

of variation of enzyme E

k

on enzyme E

j

, we defined the

redistribution coefficient (a

kj

) as the ratio of an infinitesimal

change in the concentration E

j

to an infinitesimal change in

the concentration E

k

:

akj ¼@Ej

@Ekð1Þ

In this framework, the enzyme concentrations become

interdependent parameters.

Combined response coefficient of the flux. If an effector p

acts on the flux through its effect on enzyme j, the response

4376 S. Lion et al.(Eur. J. Biochem. 271)FEBS 2004

coefficient R

J

p

is the product of the flux response coefficient

with respect to enzyme jand the elasticity of enzyme jwith

respect to p[1]:

RJ

p¼CJ

jej

p

Let us now assume that the effector pacts on more than

one enzyme in a metabolic pathway. We can define the

overall, multisite response obtained from the nenzymes of

the system as [44,45]:

RJ

p¼X

n

j¼1

CJ

jej

p

This is only true for very small changes in pbecause the

response coefficient is defined as a first order approxima-

tion. For a large change in p, we should add correction

terms to account for nonlinearities.

Considering an effector pcausing the redistribution of

enzyme concentrations through the modification of con-

centration E

k

of the enzyme E

k

(e.g. pis a mutation causing

an increase of E

k

and consequently modification of other

enzyme concentrations), we can write, replacing pby E

k

:

RJ

Ek¼X

n

j¼1

CJ

jej

k

Assuming that the response of an isolated reaction is

directly proportional to change in enzyme concentration, we

have:

ej

k¼Ek

Ej

akj

so that

RJ

Ek¼EkX

n

j¼1

CJ

j

akj

Ejð2Þ

We call RJ

Ekthe combined response coefficient [46]. We

will show later (in the case of a linear metabolic pathway)

that the combined response coefficient can be equivalently

written as:

RJ

Ek¼Ek

J

@J

@Ek

where the partial derivative is taken on a set of enzyme

concentrations that describes the correlations between

enzymes.

Biologically speaking, this means that the combined

response coefficient contains information about the corre-

lations between the enzyme concentrations, hence the term

ÔcombinedÕ. We can see the combined response coefficient

as a Ôresponse coefficient under constraintÕ. We can split

Eqn 2 into two terms:

RJ

Ek¼CJ

kakk þEkX

j6¼k

CJ

j

akj

Ej

Note that a

kk

¼1 (Eqn 1), so that

RJ

Ek¼CJ

kþEkX

j6¼k

CJ

j

akj

Ejð3Þ

TheeffectofavariationofenzymeE

k

on the flux appears

then to be dependent on two factors: (a) the control exerted by

enzyme E

k

on the flux, and (b) the effect of enzyme E

k

on the

others, through the redistribution rules, which is modulated

by the control exerted by those enzymes on the flux. Thus,

even if enzyme E

k

has a high control coefficient on the flux, an

increase of E

k

should cause a decrease of the flux if E

k

is

negatively correlated with the concentrations of other

enzymes. We can also note that the response coefficient of

enzyme E

k

will be higher than its control coefficient in cases

where enzyme E

k

is positively correlated with at least one

other enzyme of the pathway, and not correlated to the others.

Thus, we have given a general expression for the

combined response coefficient of the flux, valid for a

networkofanycomplexity,withnoassumptionontherules

of redistribution of enzyme concentrations. In the next

paragraph, we will present the theoretical framework that

allowed us to describe the linear correlations between

enzyme concentrations, and in the second part of the

paper we will analyse in detail the particular case of a linear

pathway of enzymes far from saturation, considering the

response of both flux and metabolite concentrations.

Linear models of redistribution of enzyme

concentrations

We assumed linear redistribution, which means that a

kj

is

considered to be constant.

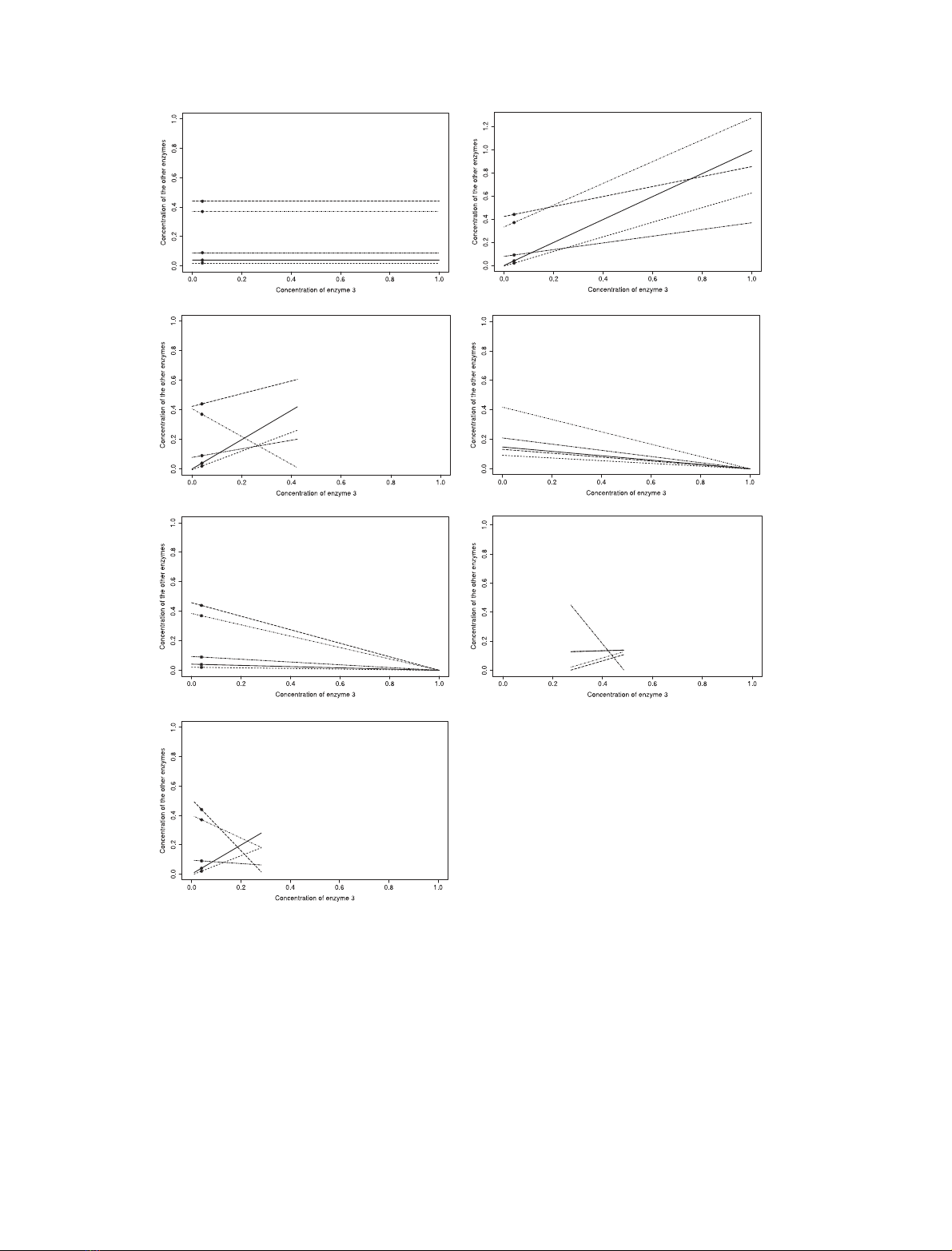

Figure 1 shows how enzyme concentrations are redis-

tributed due to their correlations. Figure 1A corresponds to

the case of independent enzyme concentrations that was

studied in the founding papers of the metabolic control

theory [1,2]. Figure 1B–G corresponds to various con-

straints that result in a redistribution of enzyme concentra-

tions over the variation of a particular enzyme.

Let us examine these constraints, the mathematical

expressions of which are summarized in Table 1. We focus

on a linear model of redistribution of enzyme concentra-

tions but other models are possible. Let us further introduce

the normalized concentration e

j

defined as:

ej¼Ej

Etot

where

Etot ¼X

n

j¼1

Ej

Competitive correlations. In order to take into account the

fact that enzyme concentrations are likely to be bounded,

Heinrich et al. [47–49], and de Vienne et al. [46], have

proposed to put a constraint on the total concentration E

tot

of the enzymes in the pathway. In this paper, this is designed

as competition and we limit the study to the quite rigid

constraint where E

tot

is a constant. We have:

X

n

j¼1

Ej¼Etot ¼const

Using the normalized concentration e

j

, the competitive

constraint on the metabolic pathway reads

X

n

j¼1

ej¼1ð4Þ

FEBS 2004 An extension to the metabolic control theory (Eur. J. Biochem. 271) 4377

In systems with only competitive constraints, the con-

centrations of enzymes E

j

("j„k) decrease when the

concentration of enzyme E

k

increases and the proportions

of enzymes E

j

remain constant. So we can define the

competition coefficient c

kj

between enzymes E

k

and E

j

(i.e.

the constant proportion between these enzymes) as

AB

CD

EF

G

Fig. 1. Redistribution of enzyme concentrations when the concentration of the target enzyme changes. We considered a six-enzyme pathway. E

3

is the

concentration of the target enzyme. The y-axis shows the concentrations of enzymes E

1

,E

2

,E

4

,E

5

and E

6

. Unless otherwise stated, the starting

distribution of enzyme concentrations is the vector E

0

¼(0.04,0.02,0.04,0.37,0.44,0.09), indicated with dots on the figures. The concentration of

the target enzyme varies either between 0 and E

tot

¼1, or between E

3,min

and E

3,max

, depending on the constraints imposed on the system.

(A) Independence between enzyme concentrations. (B) Pure regulation with positive correlations. The redistribution coefficients are a

3

¼b

3

¼

(0.99,0.63,1,0.94,0.43,0.29). (C) Pure regulation with one enzyme being negatively correlated. a

34

¼)0.94, the other redistribution coefficients being

the same as in (B). (D) Competition when the starting distribution of enzyme concentrations is the optimal one, which maximizes the flux. (E)

Competition when the starting distribution of enzyme concentrations is E

0

. (F) Regulation with competition. The starting distribution of enzyme

concentrations is E

1

¼(0.13,0.13,0.31,0.04,0.02,0.37) and the redistribution coefficients are a

3

¼(0.05,0.05,1,0.5,0.5,-2.1). (G) Regulation with

competition when the starting distribution of enzyme concentrations is E

0

and coregulation coefficients b(Eqn 6) are as in (B).

4378 S. Lion et al.(Eur. J. Biochem. 271)FEBS 2004

8j6¼ kckj ¼ ej

1ekð5Þ

Thus partial derivation of Eqn 5 with respect to e

k

leads to

@ej

@ek¼ckj

and we have c

kk

¼1. As by definition akj ¼@ej

@ek,wehave

for pure competitive systems, a simple relationship between

competition and redistribution coefficients (Table 1,

Appendix A):

8j6¼ kakj ¼ckj ¼ ej

1ek

akk ¼ckk ¼1

which can also be derived from summation of Eqn 5.

Regulatory correlations. When redistribution of enzyme

concentrations is only due to regulatory mechanisms, total

enzyme content has no upper limit, but enzyme concen-

trations are correlated. Variation of the concentration of

enzyme E

k

from E

k

to E00

kdrives the system to a new state

E00

1; :::; E00

j; :::; E00

n,where

8jE

00

j¼Ejþbkj ðE00

kEkÞð6Þ

where E

j

is the concentration of enzyme E

j

before the

variation of enzyme E

k

,andb

kj

is the coregulation

coefficient between enzymes E

j

and E

k

. The coefficients

can be positive, negative or null, but at least one is different

from 0. It is worth noting that b

kk

¼1.

In systems with only regulatory constraints, the coregu-

lation coefficient corresponds to the redistribution coeffi-

cient, i.e. a

kj

¼b

kj

, as shown in Appendix A (also Table 1).

Redistribution coefficients in competitive-regulatory path-

ways. When both competition and regulation are present in

a pathway, it is interesting to note that a simple relationship

exists between the redistribution coefficient a

kj

and the

coregulation coefficients b

kj

(Appendix A):

akj ¼bkj ejBk

1ekBkð7Þ

where

Bk¼X

n

j¼1

bkj:

This relationship does not involve explicitly the competi-

tion coefficient c

kj

. But when there is no coregulation in the

system, we have "j„kb

kj

¼0andB

k

¼b

kk

¼1, so that:

akj ¼ ej

1ek¼ckj

Application: the case of a linear pathway

of enzymes

We applied our model of redistribution of enzyme con-

centrations to the linear pathway of enzymes far from

saturation studied by Kacser & Burns [1].

Flux and metabolite concentrations in a linear pathway

Let us consider a linear metabolic pathway, with n enzymes

E

1

,E

2

,…,E

n

converting a substrate X

0

into a final product

X

n

by a series of unimolecular reversible reactions:

X0¢

E1S1¢

E2S2¢

E3... ¢

En2Sn2¢

En1Sn1¢

EnXn

The enzymes are supposed to be Michaelian and far from

saturation. The steady-state flux through the pathway is

[1,2]:

J¼X

P

n

j¼1

1

Vj

MjK0;j1

ð8Þ

and the steady-state concentration of metabolite S

i

is

Si¼J

XK0;iX0X

j>i

1

Vj

MjK0;j1þXn

K0;nX

ji

1

Vj

MjK0;j1

0

@1

Að9Þ

where X

0

and X

n

are the concentrations of substrate X

0

and

product X

n

, respectively, and X¼X

0

)X

n

/K

0,n

.X

0

and X

n

are considered as fixed parameters of the systems, while the

intermediate metabolite concentrations S

i

(1 £i£n)1)

are variables. V

k

is the maximum velocity of enzyme E

k

,M

k

is its Michaelis constant, and K0;k¼Qk

j¼1Kj1;jis the

product of the equilibrium constants of reactions 1, 2,…,k.

To make apparent the concentration of enzymes, E

k

,in

Eqns 8 and 9, we used the relationship:

Vk¼kcat;kEk

where k

cat,k

is the turnover number of enzyme E

k

.

We can then define the activity parameter A

k

of enzyme

E

k

by:

Ak¼kcat;k

Mk

K0;k1

with K

0,0

¼1 by convention.

Table 1. Mathematical expressions of the redistribution coefficients of

enzyme concentrations a

kj

when introducing competitive and/or regula-

tory constraints. a

kj

is the ratio of a change in the concentration E

j

to a

change in the concentration E

k

. Note that values of a

kj

are only true for

j„kbecause a

kk

is always equal to unity. The subscript krefers in this

table to the enzyme whose concentration we want to vary, for instance

through experimental or genetic means (see Appendices A to D for

more details).

No competition

(E

tot

is not constant)

Competition

(E

tot

is constant)

No regulation 8j6¼ kakj ¼0

akk ¼18j6¼ kakj ¼ckj ¼ ej

1ek

akk ¼ckk ¼1

X

n

j¼1

ckj ¼0

Regulation 8j6¼ kakj ¼bkj

bkk ¼18j6¼ kakj¼bkj ejBk

1ekBk

akk ¼1

Xn

j¼1akj ¼0

FEBS 2004 An extension to the metabolic control theory (Eur. J. Biochem. 271) 4379