MINIREVIEW

Barrier passage and protein dynamics in enzymatically catalyzed

reactions

Dimitri Antoniou

1

, Stavros Caratzoulas

1,

*, C. Kalyanaraman

1

, Joshua S. Mincer

1

and Steven D. Schwartz

1,2

1

Department of Biophysics, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA;

2

Department of Biochemistry, Albert Einstein

College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA

This review describes studies of particular enzymatically

catalyzed reactions to investigate the possibility that catalysis

is mediated by protein dynamics. That is, evolution has

crafted the protein backbone of the enzyme to direct vibra-

tions in such a fashion to speed reaction. The review presents

the theoretical approach we have used to investigate this

problem, but it is designed for the nonspecialist. The results

show that in alcohol dehydrogenase, dynamic protein

motion is in fact strongly coupled to chemical reaction in

such a way as to promote catalysis. This result is in concert

with both experimental data and interpretations for this and

other enzyme systems studied in the laboratories of the two

other investigators who have published reviews in this issue.

Keywords: protein dynamics; enzyme catalysis; tunneling;

promoting vibration; promoting mode.

INTRODUCTION

The transmission of an atom or group of atoms from the

reactant region of a reaction to the product region under the

control of an enzyme is central to biochemistry. The manner

in which the enzyme speeds this transfer is in some cases still

not clear. What is known is the end effect; enzymatic

reactions occur at rates many orders of magnitude more

rapid than the corresponding solution phase reactions. This

review will describe work recently completed in our group

that has focused on examining the possibility that protein

dynamics may in some enzymes play a central role in helping

to produce the catalytic effect. These types of motions,

which we have termed rate promoting vibrations,are

motions of the protein matrix that change the geometry of

the chemical barrier to reaction. By this we mean that both

the height and width of the barrier are changed. This unique

role for the protein matrix has significant implications for

the dynamics of the chemical reaction; in particular, causing

a barrier to narrow can significantly enhance a light

particle’s ability to tunnel, while masking the normal kinetic

indicators of such a phenomenon. It is this feature that we

have proposed as a unifying principle for some experimental

data relating to tunneling in enzymatic reactions.

This paper will describe our studies of rate promoting

vibrations in enzymatic reactions with particular attention

to the physical origins of the phenomenon. The structure of

this paper will be as follows: in the next section, we will

briefly review a number of different potential mechanisms

for enzyme catalytic action along with promoting vibra-

tions. Following this, we will describe the mathematical

foundation for our theories in some detail. This section will

be written for nonexperts, but will contain the necessary

formulae for the specialist as well. It will include the

relationship between the current theories and a well-known

approach to charged particle transfer in biological reactions,

namely the Marcus theory. In this section we will also

describe a simple nonbiological chemical system in which

the physical features of promoting vibrations may be easily

understood – proton transfer in organic acid crystals. We

will then describe how we have used these concepts to fit

seemingly anomalous kinetic data for enzymatic reactions.

In the next section, we explore how one might rigorously

identify the presence of such a promoting vibration in any

enzymatic reaction, and illustrate the concepts with appli-

cations to specific enzyme systems. The paper then con-

cludes with discussions of future directions for this research.

POTENTIAL MODES OF ENZYMATIC

ACTION

The exact physical mechanisms by which enzymes cause

catalysis is still a topic for vigorous dialogue [1–3]. The

research described in this paper will argue for a strong

contribution from a nontraditional source, i.e. directed

protein motions. In order to place this concept into a

context, we will briefly review other potential mechanisms

for enzymes to cause catalysis. We emphasize that none of

these mechanisms are mutually exclusive, and are probably

all involved in catalysis to a greater or lesser extent in each

enzyme system.

One of the earliest and still widely accepted ideas used to

explain this catalytic efficiency is the transition state-binding

concept of Pauling [4]. In this picture, as a chemical

substance is being transformed from reactants to products,

the species that binds most strongly to the enzyme is at some

Correspondence to S. D. Schwartz, 1300 Morris Park Ave.,

Bronx, NY 10461, USA. Tel.: + 1 718 430 2139,

E-mail: sschwartz@aecom.yu.edu

Abbreviations: NAC, near attack conformations; HLADH, horse liver

alcohol dehydrogenase; YADH, yeast alcohol dehydrogenase.

Note: a website is available at http://www.aecom.yu.edu/home/sggd/

faculty/schwartz.htm

*Present address: Department of Chemical Engineering, Princeton

University, NJ, USA.

(Received 8 March 2002, revised 31 May 2002, accepted 6 June 2002)

Eur. J. Biochem. 269, 3103–3112 (2002) FEBS 2002 doi:10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03021.x

intermediate point thought to be at or near the top of the

solution phase (i.e. uncatalyzed) barrier to reaction. This

preferential binding releases energy that stabilizes the

transition state and thus lowers the barrier to reaction. This

is a standard picture for nonbiological catalysis, and it also

has significant experimental support. A critical observation

is found using kinetic isotope effect methods. In this way,

one can probe the chemical structure of the transition state

in the catalytic event. Stable molecules can be designed that

share the electronic properties of the transition state (usually

identified by the electrostatic potential at the van der Waals

surface). Furthermore, these molecules make highly potent

inhibitors [5,6]. When substrate-like molecules that cannot

react to form products bind, often a far lower level of

inhibition is found. This result is said to be indicative of the

fact that the transition state is strongly bound. It has been

argued, however, that the electrostatic character of the

active site during the catalytic event is largely determined by

whatever charge stabilization is needed as the reaction

progresses. If an inhibitor is designed with the complement-

ary charges, it will bind strongly to the active site. However,

this does not imply that the method by which the enzyme

produced catalysis was transition state binding and con-

comitant release of energy [1].

A second approach, which might be viewed as the

converse of transition state stabilization, is ground state

destabilization. In this picture [7], the role of the enzyme is to

make the reactants less stable rather than making the

transition state more stable. Thus the energetic hill that must

be climbed with thermal activation is lowered. Energies are

all relative and so the end effect of this and the first

mechanism are the same; lowering the relative energy

difference between reactants and transition state. But it is

clear that this view presents a very different physical

mechanism. Recent calculations [8] seem to show that this

model may well be dominant for the most efficient enzyme

known, orotidine monophosphate decarboxylase.

A third concept that has been also suggested. In solution,

reactants are strongly solvated by water, the dominant

component of most living cells. When enzymes bind

reactants, they often exclude water, and this lowered

dielectric environment may be more conducive to reaction

[9–11]. This approach to catalysis tends to treat the catalytic

event much like an electron transfer reaction in solution.

The dominant description of electron transfer in solution is

Marcus’ theory [12], and this approach has also been used to

describe atom transfer [13]. The concept here is that the

main barrier to reaction is, in fact, reorganization of the

solvent as charged particles move, rather than the intrinsic

chemical barrier due to transformation of the substrate. It is

certainly true that such energy reorganization may be a

significant component in many cases, but probably does not

account for all catalysis in biological systems.

A fourth recent suggestion by Bruice [14,15] is that the

dominant role of an enzyme is to position substrates in such

a way that thermal fluctuations easily take them over the

barrier to reaction. The set of positions the enzyme

encourages the substrate to take are known as near attack

conformations(NACs). Here, while the enzyme might bind

strongly to a transition state structure, this binding energy is

not thought to be released specifically to speed the reaction.

The enzyme moulds the substrate so that it is on the edge of

reacting and forming products. Because the enzyme helps

the reactants to form the NAC, this view is philosophically a

bit closer to the ground state destabilization view. It is,

however, not a statistical energetic argument, but rather a

chemical structure argument.

A fifth possibility for the mode of action of enzymes is the

principle subject of this paper, that is, motions within the

protein itself actually speed the rate of a chemical reaction.

There is significant relation between this possibility and the

last view of catalysis described above, i.e. the creation of the

NAC. It must be stressed, however, that the current view is a

dynamic one. For this concept to be true, actual motions of

the protein must couple strongly to a reaction coordinate

and cause an increase in reaction rate. This is not simply

preparation of a reactive species, but rather dynamic

coupling. It is important to note that this is an entirely

different view of the method by which the enzyme

accomplishes rate acceleration. In this view, evolution has

created a protein structure that moves in such a way as to

lower a barrier and make it less wide. It must be emphasized

that this lowering of the barrier is not statistical lowering of

a potential of mean force through the release of binding

energy, but rather the use of highly directed energy (a

vibration) in a specific direction. Furthermore, this is not

simply the statistical preparation of reactive species as in the

NAC concept. Here, protein dynamics directly affect the

reaction coordinate potential. Although this effect can be

quite apparent for a tunneling system (the probability to

tunnel increases exponentially with a reduction of the width

of the tunneling barrier), it is equally important for systems

where the reaction proceeds through classical transfer,

because as the barrier is made narrower, it is also lowered.

In order to understand how directed protein motions may

cause catalysis, we need a theory of chemical reactions in a

condensed phase. Our group has developed theories over

the past 10 years, and this work, initially developed for

simple condensed phases, such as polar media, forms the

basis for our analysis. We now describe these theories in

some detail.

AN ENZYME AS A CONDENSED PHASE:

THEORETICAL FORMULATION FOR

THE STUDY OF CHEMICAL REACTION

There are two requirements to enable the study of a

chemical reaction in any system, be it as simple as a gas

phase collision, or as complex as that in an enzyme. First, a

potential energy for the interaction of all the atoms in the

system is needed. This includes the interactions of all atoms

having their chemical bonds changed, and those that do not.

The second requirement is for a method to solve the

dynamics of the equations of motion that allow one to

follow the progress of the reacting species in the presence of

the rest of the system from reactants to products. In this

work, we assume that we are able to obtain the first

requirement (the potential). In order to study the dynamics

on this potential, however, one needs to solve the Schro-

dinger equation for the entire collection of atoms. It is a

well-known fact that this is difficult for three or four atoms,

and so essentially impossible for the thousands of atoms in a

reaction catalyzed by an enzyme.

Various groups have taken a number of possible

approaches to solve this problem. One may assume that

quantum effects are minor, and use a purely classical

3104 D. Antoniou et al. (Eur. J. Biochem. 269)FEBS 2002

approach to solve the dynamics [16]. We are specifically

interested in studies of enzyme systems where quantum

mechanics plays a significant role, through tunneling of a

light particle, in the chemical step of the enzyme, and so the

classical approach will not be expected to yield valid results.

Another approach is to use a mixed quantum-classical

formulation in which a subset of the atoms is treated

quantum mechanically and the rest of the system is treated

purely classically. In recent years, this approach has become

popular with the pioneering work of such investigators as

Gao [8]. We have chosen a different approach, largely on

stylistic grounds. Rather than treating the full collection of

atoms as a mixture of quantum and classical objects

(something that is difficult to define rigorously), we have

developed approximate approaches to treat the entire

collection of atoms as a quantum mechanical entity. As

mentioned above, both approaches are approximate, but we

prefer to make the approximation uniform for the entire

system.

We have called our approach the Quantum Kramers

methodology [17,18]. Our ideas were motivated by the

following approximations developed for the study of the

classical mechanics of large, complex systems. It is known

that for a purely classical system [19,20], an accurate

approximation of the dynamics of a tagged degree of

freedom (for example a reaction coordinate) in a condensed

phase can be obtained through the use of a generalized

Langevin equation. The generalized Langevin equation is

given by Newtonian dynamics plus the effects of the

environment in the form of a memory friction and a random

force [21]. Thus, all the complex microscopic dynamics of all

degrees of freedom other than the reaction coordinate are

included only in a statistical treatment, and the reaction

coordinate plus environment is treated as a modified one-

dimensional system. What allows a realistic simulation of

complex systems is that the statistics of the environment can

in fact be calculated from a formal prescription. This

prescription is given by the fluctuation-dissipation the-

orem, which yields the relationship between friction and

random force. In particular, this theory enables us to

calculate the memory friction from a relatively short-time

classical simulation of the reaction coordinate. The Quan-

tum Kramers approach, in turn, is dependent on an

observation of Zwanzig [22,23]; if an interaction potential

for a condensed phase system satisfies a fairly broad set of

mathematical criteria, the dynamics of the reaction coordi-

nate as described by the generalized Langevin equation can

be rigorously equated to a microscopic Hamiltonian in

which the reaction coordinate is coupled to an infinite set of

Harmonic Oscillators via simple bilinear coupling:

H¼P2

s

2ms

þVoþX

k

P2

k

2mk

þ1

2mkx2

kqkcks

mkx2

k

2

ð1Þ

The first two terms in this Hamiltonian represent the kinetic

and potential energy of the reaction coordinate, and the last

set of terms similarly represent the kinetic and potential

energy for an environmental bath. Here, srepresents some

coordinate that measures progress of the reaction (for

example, in alcohol dehydrogenase where the chemical

step is transfer of a hydride, smight be chosen to represent

the relative position of the hydride from the alcohol to the

NAD cofactor.) c

k

is the strength of the coupling of the

environmental mode to the reaction coordinate, and m

k

and x

k

give the effective mass and frequency, respectively,

of the environmental bath mode. A discrete spectral density

gives the distribution of bath modes in the harmonic

environment:

JðxÞ¼p

2X

k

c2

k

mkxk

dðxxkÞdðxþxkÞ

½

ð2Þ

Here d(x)x

k

)istheDirac deltafunction, so the spectral

density is simply a collection of spikes, located at the

frequency positions of the environmental modes, weighted

by the strength of the coupling of these modes to the

reaction coordinate. Note that this infinite collection of

oscillators is purely fictitious; they are chosen to reproduce

the overall physical properties of the system, but do not

necessarily represent specific physical motions of the atoms

in the system. It would seem that we have not made a huge

amount of progress; we began with a many-dimensional

system (classical) and found out that it could be accurately

approximated by a one-dimensional system in a frictional

environment (the generalized Langevin equation.) We have

now recreated a many-dimensional system (the Zwanzig

Hamiltonian). The reason we have done this is twofold.

First, there is no true quantum mechanical analogue of

friction, and so there really is no way to use the generalized

Langevin approach for a quantum system, such as we

would like to do for an enzyme. Second, the new quantum

Hamiltonian given in Eqn (1) is much simpler than the

Hamiltonian for the full enzymatic system. Harmonic

oscillators are a problem that can easily be solved by

quantum mechanics. Thus, the prescription is, given a

potential for the enzymatic reaction, we model the exact

problem using Zwanzig Hamiltonian, as in Eqn (1), with

the distribution of harmonic modes given by the spectral

density in Eqn (2), and found through a simple classical

computation of the frictional force on the reaction coordi-

nate. Then, using methods to compute quantum dynamics

developed in our group [24–29], quantities such as rates or

kinetic isotope effects may be computed. Thus, the quantum

Kramers method, developed in our group, consists of the

following ingredients. Given a potential for the enzymatic

reaction, we model the exact problem using Zwanzig’s

Hamiltonian, as in Eqn (1), with the distribution of

harmonic modes given by the spectral density in Eqn (2).

The spectral density is obtained through a molecular

dynamicssimulation of the classical system. Then, using

methods developed in our group to carry out the quantum

dynamics, quantities such as rates or kinetic isotope effects

may be computed.

This approach enables us to model a variety of condensed

phase chemical reactions with essentially experimental

accuracy [30]. There are deeper connections between this

approach and another popular method of dynamics com-

putation in complex systems. We have shown [30] that this

collection of bilinearly-coupled oscillators is in fact a

microscopic version of the popular Marcus theory for

charged particle transfer [12,13]. The bilinear coupling of the

bath of oscillators is the simplest form of a class of couplings

that may be termed antisymmetric because of the mathe-

matical property of the functional form of the coupling on

reflection about the origin. This property has deeper

implications than the mathematical nature of the symmetry

FEBS 2002 Barrier passage and protein dynamics (Eur. J. Biochem. 269) 3105

properties. Antisymmetric couplings, when coupled to a

double-well-like potential energy profile, are able to instan-

taneously change the level of well depths, but do nothing to

the position of well minima. This modulation in the position

of minima is exactly what the environment is envisaged to

do within the Marcus theory paradigm. As we have shown

[30], the minima of the total potential in Eqn (1) will occur,

for a two-dimensional version of this potential, when the q

degree of freedom is exactly equal and opposite in sign to

cs

mx2, and the minimum of the potential energy profile along

the reaction coordinate is unaffected by this coupling.

Within Marcus’ theory, which is a deep tunneling theory,

transfer of the charged particle occurs at the value of the

bath coordinates that cause the total potential to become

symmetrized. Thus, if the bare reaction coordinate potential

is symmetric, then the total potential is symmetrized at the

position of the bath plus couplingminimum. When this

configuration is achieved, the particle tunnels; the activation

energy for the reaction is largely the energy to bring the bath

into this favorable tunneling configuration.

While Marcus’ theory and our microscopic quantum

Kramers theory are highly successful in many cases, in other

cases, it is not possible to reproduce experimental results

using such an approach. The reason for this is that the

antisymmetric coupling contained within the Zwanzig

Hamiltonian does not physically represent all possible

important motions in a complex reacting system. In fact,

such a reality was pointed out some time ago in seminal

work of the Hynes group [31]. In some of our earlier work

on hydrogen transfer in enzymatic systems, we were able to

show that one could reasonably fit experimental kinetic data

in such enzymatic systems with phenomenological applica-

tion of the Hynes theories [32]. We became interested in a

microscopic study of such systems in the examination of

nonbiological proton transfer reactions, i.e. organic acid

crystals. The simplest example is a carboxylic acid dimer,

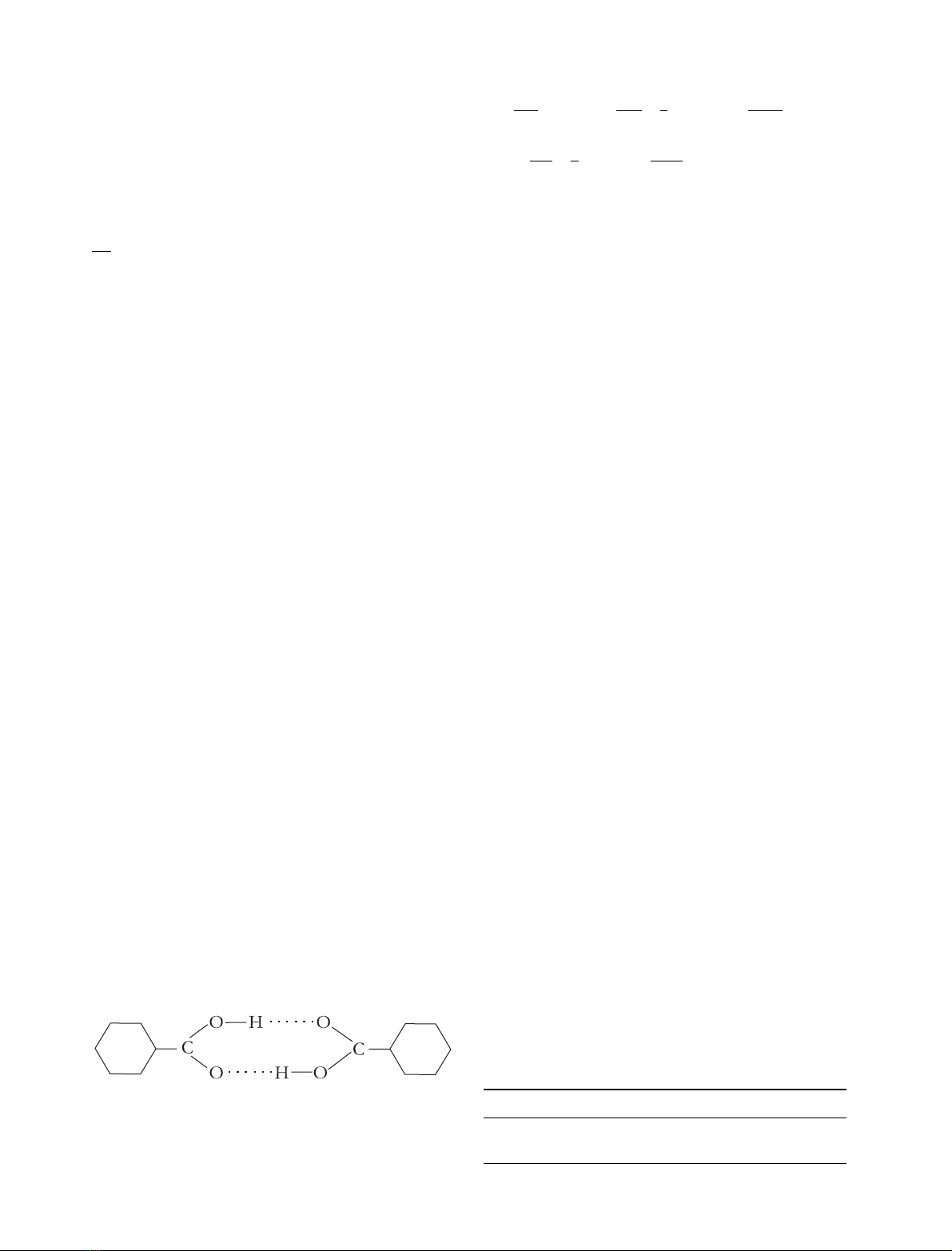

showninFig.1.Suchsystemshadbeenstudiedformany

years [33–37], and they presented what seemed to be a

chemical physics conundrum. While quantum chemistry

computations seemed to show that the intrinsic barrier to

proton transfer in these systems was reasonably high, and

low experimental activation energies seemed to indicate a

significant involvement of quantum tunneling in the proton

transfer mechanism, careful measurements of kinetic iso-

tope effects showed kinetics indicative of classical transfer.

In order to study such systems, a rigorous theory, which

allowed inclusion of symmetrically coupled vibrations, in

addition to an environmental bath of antisymmetrically

coupled oscillators, was needed. Mathematically, the simp-

lest transformation of the Hamiltonian in Eqn (1) is given

by:

H¼P2

S

2ms

þVoþX

k

P2

k

2mk

þ1

2mkx2

kqkcks

mkx2

k

2

þP2

Q

2Mþ1

2mX2QCs2

MX2

ð3Þ

Note that in this case, the oscillator that is symmetrically

coupled, represented by the last term in Eqn (3), is in fact a

physical oscillation of the environment.

We were able to develop a theory [38] of reactions

mathematically represented by the Hamiltonian in Eqn (3),

and using this method and experimentally available param-

eters for the benzoic acid proton transfer potential, we were

able to reproduce experimental kinetics as long as we

included a symmetrically coupled vibration [39]. The results

are shown in Table 1 below. The two-dimensional activa-

tion energies refer to a two-dimensional system comprised

of the reaction coordinate and a symmetrically coupled

vibration. The reaction coordinate is also coupled to an

infinite environment as described above.

In this case, the symmetric motion has a clear physical

origin: the symmetric motion of the carbonyl and hydroxyl

oxygen atoms toward each other. Kinetic isotope effects in

this system are modest, even though the vast majority of the

proton transfer occurs via quantum tunneling. The end

result of this study is that symmetrically coupled vibrations

can significantly enhance rates of light particle transfer, and

also significantly mask kinetic isotope signatures of tunnel-

ing. A physical origin for this masking of the kinetic isotope

effect may be understood from a comparison of the two-

dimensional problem comprised of a reaction coordinate

coupled symmetrically and antisymmetrically to a vibration.

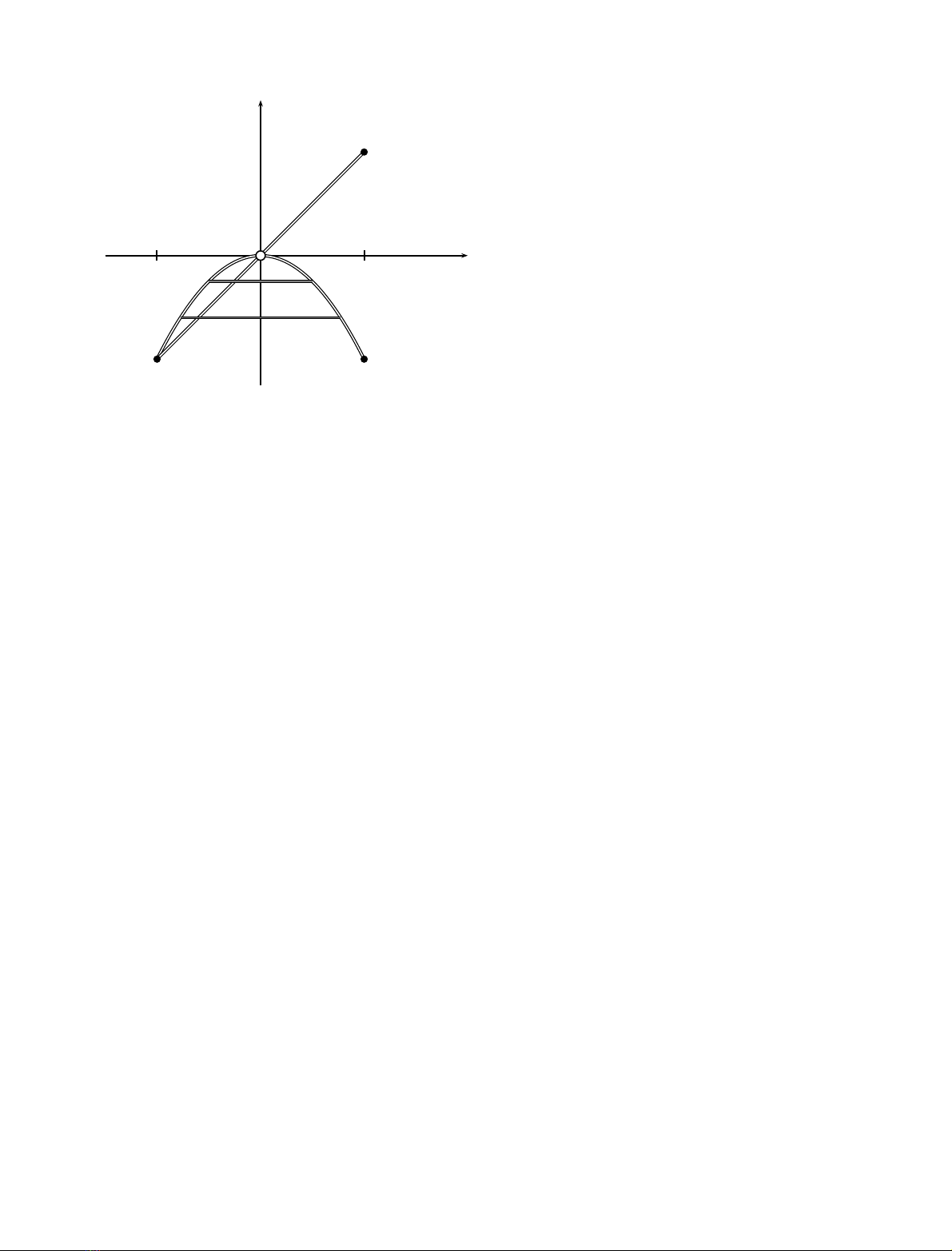

As Fig. 2 shows, antisymmetric coupling causes the minima

(the reactants and products) to lie on a line; the minimum

energy path, which passes through the transition state. In

contrast, symmetric coupling causes the reactants and

products to be moved from the reaction coordinate axis in

such a way that a straight line connection of reactant and

products would pass no where near the transition state.

This, in turn, results in the gas phase physical chemistry

phenomenon known as corner cutting [40–42]. Physically,

the quantity to be minimized along any path from reactant

to products is the action. This is an integral of the energy,

and so loosely speaking, it is a product of distance and depth

under the barrier that must be minimized to find an

approximation to the tunneling path. The action also

includes the mass of the particle being transferred, and so in

the symmetric coupling case, a proton will actually follow a

very different physical path from reactants to products in a

reaction than a deuteron. (Not just in the trivial sense that

one tunnels more than another). It is this following of a

different physical path, even when tunneling dominates,

Fig. 1. A benzoic acid dimer. Thereactioncoordinateinthiscaseisthe

symmetric transfer of the hydroxyl protons to the carbonyl oxygen.

The promoting vibration is the symmetric motion of the oxygens

toward each other.

Table 1. Activation energies for H and D transfer in benzoic acid

crystals at T ¼300 K. Three values are shown: the activation energies

calculated using a one- and two-dimensional Kramers problem and the

experimental values. The values of energies are in kcalÆmol

)1

.

E

1d

E

2d

Experiment

H 3.39 1.51 1.44 kcalÆmol

)1

D 5.21 3.14 3.01 kcalÆmol

)1

3106 D. Antoniou et al. (Eur. J. Biochem. 269)FEBS 2002

that causes the kinetic isotope effects to be masked. It was

this low level of primary kinetic isotope effect that suggested

a similarity between the proton transfer mechanism in the

organic acid crystal and that of enzymatic reactions. While

coupled motions of nearby atoms in enzymatic reactions

have been used to explain anomalous kinetic isotope effects

[43], these were studies in a classical picture with semiclas-

sical tunneling added (the Bell correction; [44]) and they

could not be used to account for enzymatic reactions in a

deep tunneling regime.

Klinman and coworkers have helped pioneer the study of

tunneling in enzymatic reactions. One focus of their work

has been the alcohol dehydrogenase family of enzymes.

Alcohol dehydrogenases are NAD

+

-dependent enzymes

that oxidize a wide variety of alcohols to the corresponding

aldehydes. After successive binding of the alcohol and

cofactor, the first step is generally accepted to be complex-

ation of the alcohol to one of the two bound Zinc ions [45].

This complexation lowers the pK

a

of the alcohol proton and

causes the formation of the alcoholate. The chemical step is

then transfer of a hydride from the alkoxide to the NAD

+

cofactor. They [46] have found a remarkable effect on the

kinetics of yeast alcohol dehydrogenase (a mesophile) and a

related enzyme from Bacillus stereothermophilus, a thermo-

phile. A variety of kinetic studies from this group have

found that the mesophile [47] and many related dehydro-

genases [48–51] show signs of significant contributions of

quantum tunneling in the rate-determining step of hydride

transfer. Remarkably, their kinetic data seem to show that

the thermophilic enzyme actually exhibits less signs of

tunneling at lower temperatures. Recent data of Kohen &

Klinman [52] also show, via isotope exchange experiments,

that the thermophile is significantly less flexible at mesophi-

lic temperatures, as in the results of Petsko et al. [53], who

conducted studies of 3-isopropylmalate dehydrogenase

from the thermophilic bacteria Thermus thermophilus.These

data have been interpreted in terms of models similar to

those we have described above, in which a specific type of

protein motion strongly promotes quantum tunneling; thus,

at lower temperatures, when the thermophile has this

motion significantly reduced, the tunneling component of

reaction is hypothesized to go down even though one would

normally expect tunneling to go up as temperature goes

down. Additionally, the Klinman group has investigated the

catalytic properties of various mutants of horse liver alcohol

dehydrogenase (HLADH). HLADH in the wild-type has a

slightly less advantageous system to study than yeast

alcohol dehydrogenase, because the chemistry is not the

rate determining step in catalysis for this enzyme. Two

specific mutations have been identified, Val203 fiAla and

Phe93 fiTrp, which significantly affect enzyme kinetics.

Both residues are located at the active site; the valine

impinges directly on the face of the NAD

+

cofactor distal to

the substrate alcohol. Modification of this residue to the

smaller alanine significantly lowers both the catalytic

efficiency of the enzyme, as compared to the wild-type,

and also significantly lowers indicators of hydrogen tunnel-

ing [54]. Phe93 is a residue in the alcohol binding pocket.

Replacement with the larger tryptophan makes it harder for

the substrate to bind, but does not lower the indicators of

tunneling [55]. Bruice’s recent molecular dynamics calcula-

tions [56] produce results consistent with the concept that

mutation of the valine changes protein dynamics, and it is

this alteration, missing in the mutation at position 93, which

in turn changes tunneling dynamics. (We note the recent

experimental results from Klinman’s group [57] in which no

decrease in tunneling is seen as the temperature is raised.)

A final set of enzymes now thought to exhibit dynamic

protein control of tunneling hydrogen transfer is that in the

amine dehydrogenase family. Scrutton and coworkers have

extensively studied these enzymes [58]. Though similarly

named and having a similar end effect as the alcohol

dehydrogenases, they employ radically different chemistry.

These enzymes catalyze the oxidative deamination of

primary amines to aldehydes and free ammonia. In this

case, however, rather than a chemical step of hydride

transfer, the rate determining chemical step is proton

transfer; and in fact these enzymes catalyze a coupled

electron proton transfer reaction. Electrons are coupled to

some cofactor, for example, in the case of aromatic amine

dehydrogenase, the cofactor is tryptophan-tryptophyl qui-

none. Kinetic studies have shown that methylamine dehy-

drogenase exhibits not only relatively large primary kinetic

isotope effects (unlike the alcohol dehydrogenases), but also

very strong temperature dependence in the measured

activation energy. This experimental data has been inter-

preted as showing that the enzyme works via a promoting

vibration [59], as we have suggested for bovine serum amine

oxidase [32], and for various forms of HLADH [60]. Here,

the primary kinetic isotope effect is 17, rather than 3 or 4.

s

q

s0+s

0

A,S S

A

Fig. 2. This diagram shows the location of stable minima in two-

dimensional systems. In one case a vibrational mode is symmetrically

coupled to the reaction coordinate, and in the other, antisymmetrically

coupled. The figure represents how antisymmetrically and symmetri-

cally coupled vibrations effect position of stable minima – that is

reactant and product wells – in modulating the one dimensional double

well potential (before coupling along the xaxis). The xaxis, s,repre-

sents the reaction coordinate, and qthe coupled vibration. The points

on the figure labeled S and A are the positions of the well minimal in

the two dimensional system with symmetric and antisymmetric coup-

ling, respectively. An antisymmetrically coupled vibration displaces

those minima along a straight line, so that the shortest distance

between the reactant and product wells passes through the transition

state. In contradistinction, a symmetrically coupled vibration, allows

for the possibility of corner cuttingunder the barrier. For example, a

proton and a deuteron will follow different paths under the barrier.

FEBS 2002 Barrier passage and protein dynamics (Eur. J. Biochem. 269) 3107