Applied Catalysis, 38 (1988) 143-155 zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Elsevier Science Publishers B.V., Amsterdam - Printed in The Netherlands

143 zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Catalytic Cracking of Heavy Oil over Catalysts

Containing Different Types of Zeolite Y in Active

and Inactive Matrices

J.-E. OTTERSTEDT*, YAN-MING ZHU’ and J. STERTE

Department of Engineering Chemistry I, Chalmers University of Technology, 412 96 Giiteborg

(Sweden)

(Received 3 July 1987, accepted 22 September 1987)

ABSTRACT

The effects of addition of alumina to the matrices of cracking catalysts containing different

types of zeolite Y, on their cracking performance, were investigated using a micro activity test and

two different feed oils.

For the heavier feed oil, the alumina addition resulted in a higher conversion at the same catalyst

to oil ratio independent of the type of zeolite. This higher conversion was accompanied by a greater

selectivity for coke and a lower selectivity for gasoline. For the lighter feed oil the effect of alumina

addition on the total conversion was much less pronounced while the effects on the selectivity

were similar to those observed using the heavier feed.

The performance of the catalysts in a commercial fluid catalytic cracking unit is discussed in

view of their coke forming tendencies and the heat balance of the cracker.

INTRODUCTION zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

In the past decade there has been a trend towards using heavier feedstocks

in fluid catalytic cracking (FCC ) . The composition of these heavy cuts have

caused problems of different kinds. The pore structure of the zeolite in zeolite

catalysts is too fine to allow fast diffusion of the large molecules present in

these fractions. Typically these feeds have high contents of metals, such as

vanadium and nickel, aromatics and compounds containing heteroatoms of

nitrogen, sulfur and oxygen. The effect of vanadium is primarily a decrease in

catalyst activity while the major effect of nickel is a selectivity change reflected

in increased coke and gas yields [ 11. The high-boiling aromatics act as coke

precursors and the increased amount of coke on the catalyst, in addition to

rapidly deactivating the catalyst, also causes problems with the heat balance

*Visiting Scholar from Yanshan Petro-Chemical Company, Peoples Republic of China.

0166-9834/ 88/ $03.50 0 1988 Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.

144 zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of the FCC unit since excess heat is produced in the regenerator when the coke

is burned off.

The selectivity problem caused by nickel contaminants can be reasonably

handled by adding nickel passivators, usually containing antimony, to the feed

[ 21. Although passivators have been reported to decrease the deactivation ef-

fects of vanadium, a more promising way to handle this problem is to introduce

vanadium “ traps” into the catalyst, which prevent the vanadium from migrat-

ing to, and destroying the zeolite [ 31. In order to meet the problem of cracking

large molecules, all major manufacturers of FCC catalysts have developed cat-

alysts containing active matrices, i.e. matrices showing a considerable cracking

activity even without the zeolite component. The idea behind this is that an

initial cracking of the molecules, too large to penetrate the zeolite structure,

occurs on the matrix surface, making a cosecutive cracking of the intermediate

species in the zeolite pores possible.

One material commonly used in commercial catalysts and reported to func-

tion both as a vanadium trap and as the active component in active matrices

is alumina [ 3 ] .

This paper reports on a systematic study of the effects of alumina addition

to the matrix of cracking catalysts, containing different types of zeolite Y, on

the cracking performance of these catalysts when cracking conventional and

heavy feed oils. Catalysts containing rare earth exchanged zeolite Y (REY) ,

calcined REY zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA(CREY) , ultrastable zeolite Y (USY ) and rare earth exchanged

USY (REUSY) in kaolin-binder and in kaolin-alumina-binder matrices were

prepared and investigated for catalytic cracking using a micro activity test.

EXPERIMENTAL zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Preparation of zeolites

A sample of rare earth exchanged zeolite Y was prepared by cation exchange

of a NaY (Katalistiks) with a solution containing a mixture of rare earth chlo-

rides (Rhone Poulenc) . The sample was exchanged three times using a solu-

tion containing 9 wt% REC& kept at 95°C for 1.0 h. After the third exchange

the sample was washed until chloride free by repetitive reslurrying in distilled

water followed by separation by filtration. The REY was dried at 120” C for 4.5

h. The CREY was prepared as follows, A sample of NaY was first subjected to

two ion exchanges with REC& as described above. The resulting zeolite was

then dried at 120°C for 4.5 h and calcined at 500°C for 2.5 h. The calcined

zeolite was then subjected to a third RE-exchange and finally to a NH,+ -ex-

change using a solution containing 20 wt% ammonium sulfate. This exchange

was also performed at 95 o C using a contact time of 1.0 h. The resulting CREY

was washed, separated and dried in the same manner as the REY.

USY was prepared by subjecting a sample of NH,Y (Katalistiks) to repet-

145

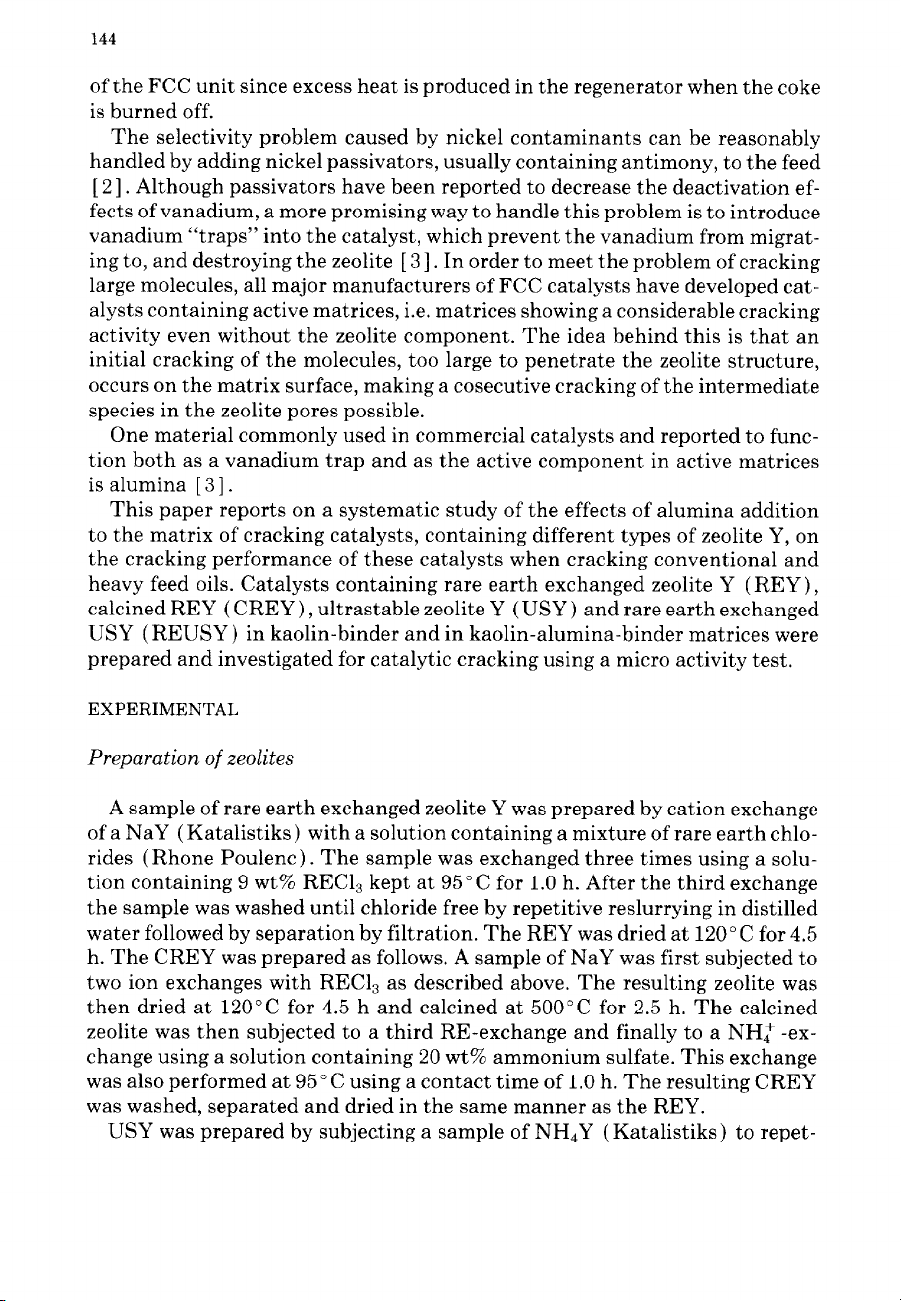

TABLE 1

Properties of zeolites used in this investigation

Zeolite

NaY

NHIY

REY

CREY

USY

REUSY

Na,O

(wt. %)

11.02

2.23

3.06

0.58

0.31

0.45

R&G

(wt. %)

-

16.3

19.3

6.9

Surface area

(m”/g)

715

537

651

610

588

583

itive (two times) exchanges with ammonium sulfate at 95 o C for 1 h. This

sample was then washed, separated and dried as described above. The cell con-

stant of the initial NH,Y was 24.55. In the steam treatment discussed below

the zeolite was stabilized by dealumination and the cell constant was reduced

to 24.24.

REUSY was prepared by subjecting a sample of NH,Y to one exchange with

ammonium sulfate and one exchange with RECl,.

During all ion-exchange procedures the pH of the solutions was kept in the

range 4.3-5.0. When required, the pH was adjusted by addition of 1.0 zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBAM am-

monium hydroxide or 1.0 M hydrochloric acid. Some important properties of

these zeolites are given in Table 1.

Preparation of catalysts

Two series of catalysts were prepared, one with a matrix containing kaolin

and a binder and a second containing kaolin, alumina and a binder. The two

types of matrices will be referred to as the inactive and active matrix, respec-

tively. In each series, one catalyst sample was prepared for each zeolite type

described above. Furthermore samples of the two matrices containing no zeo-

lite were prepared.

The catalysts containing the inactive matrix were prepared using the follow-

ing procedure: kaolin (Supreme, English China Clay) was dispersed in a di-

luted aluminum chlorohydrate solution (Locron I+ Hoechst) under vigorous

stirring. The aluminum chlorohydrate solutions, working as a binder in the

catalyst product, contained an amount of alumina corresponding to 10 wt%

alumina in the products. To the resulting slurry, zeolite was added to give a

slurry having a solids content of about 35 wt%. Amounts of zeolites corre-

sponding to 17 wt% REY, 17 wt% CREY, 22 wt% REUSY and 35 wt% USY

in the products were used. The slurries were spray dried to give catalyst par-

ticles, primarily in the range 20-100 pm, using a Niro Mobile Minor spray dryer

146

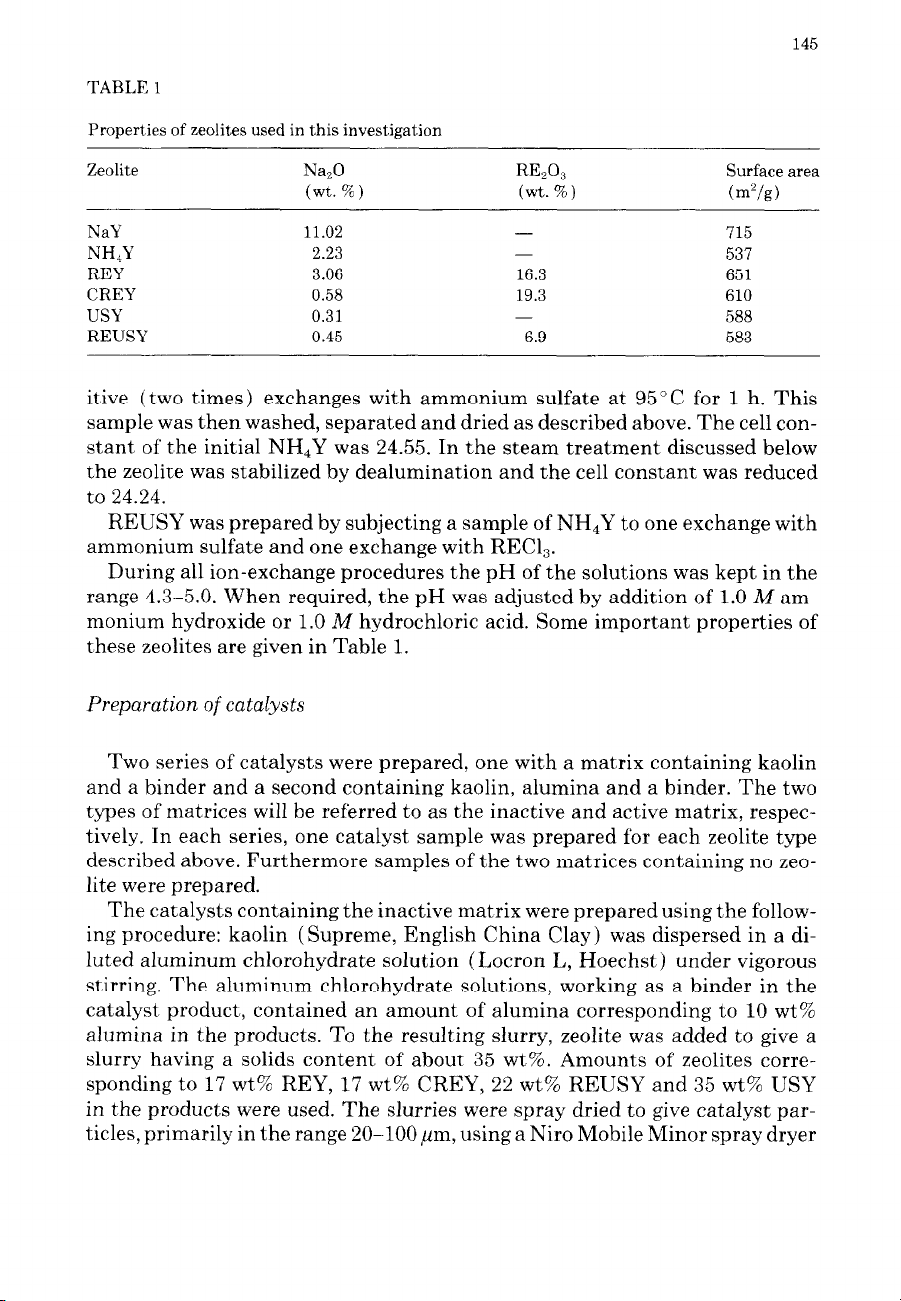

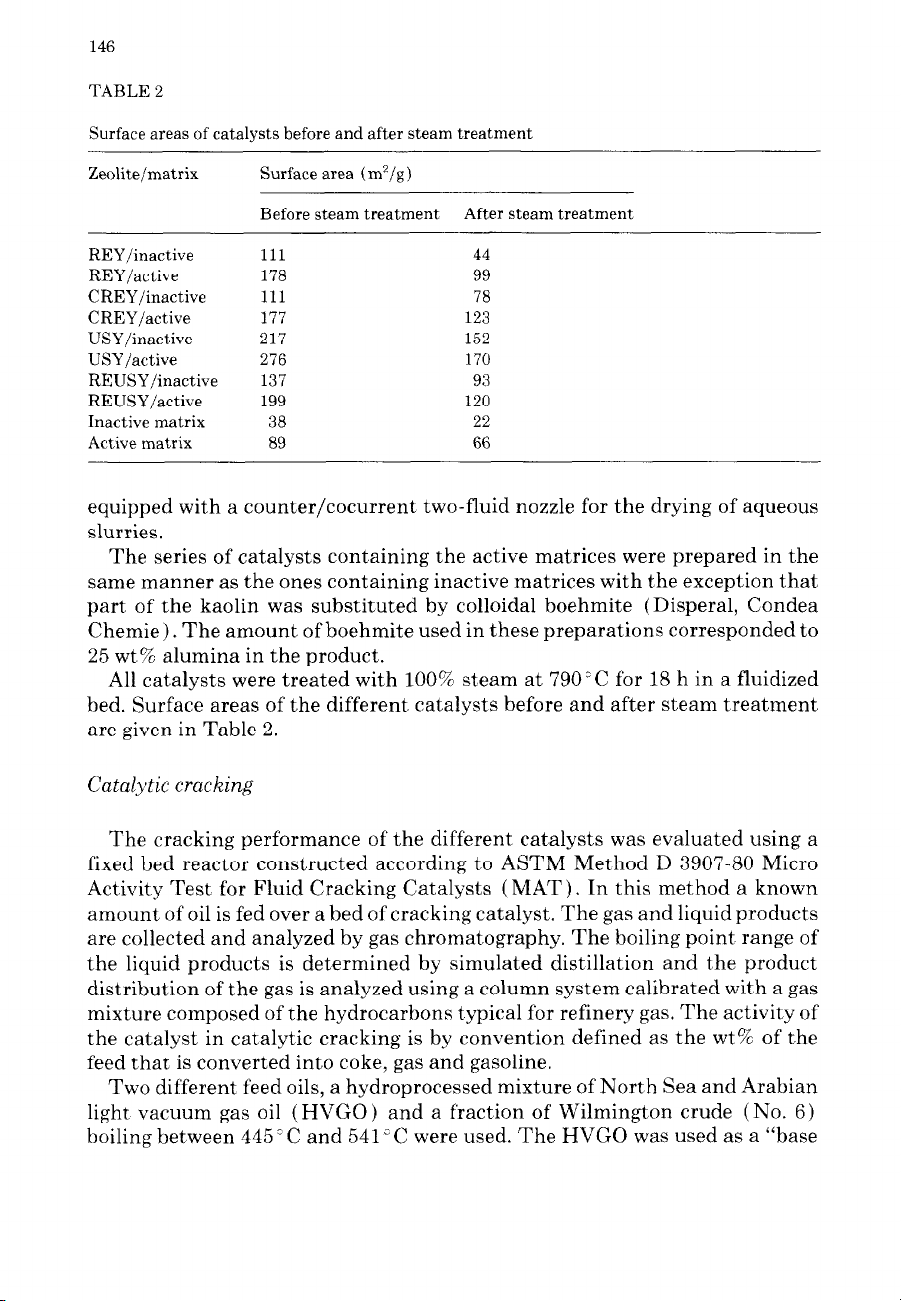

TABLE 2

Surface areas of catalysts before and after steam treatment

Zeolite/matrix Surface area (m’/g)

Before steam treatment After steam treatment

REY/inactive 111 44

REY/active 178 99

CREY/inactive 111 78

CREY/active 177 123

USY/inactive 217 152

USY/active 276 170

REUSY/inactive 137 93

REUSY/active 199 120

Inactive matrix 38 22

Active matrix 89 66

equipped with a counter/cocurrent two-fluid nozzle for the drying of aqueous

slurries.

The series of catalysts containing the active matrices were prepared in the

same manner as the ones containing inactive matrices with the exception that

part of the kaolin was substituted by colloidal boehmite (Disperal, Condea zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Chemie) . The amount of boehmite used in these preparations corresponded to

25 wt’% alumina in the product.

All catalysts were treated with 100% steam at 790°C for 18 h in a fluidized

bed. Surface areas of the different catalysts before and after steam treatment

are given in Table 2. zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Catalytic cracking

The cracking performance of the different catalysts was evaluated using a

fixed bed reactor constructed according to ASTM Method D 3907-80 Micro

Activity Test for Fluid Cracking Catalysts (MAT ) . In this method a known

amount of oil is fed over a bed of cracking catalyst. The gas and liquid products

are collected and analyzed by gas chromatography. The boiling point range of

the liquid products is determined by simulated distillation and the product

distribution of the gas is analyzed using a column system calibrated with a gas

mixture composed of the hydrocarbons typical for refinery gas. The activity of

the catalyst in catalytic cracking is by convention defined as the wt% of the

feed that is converted into coke, gas and gasoline.

Two different feed oils, a hydroprocessed mixture of North Sea and Arabian

light vacuum gas oil (HVGO ) and a fraction of Wilmington crude (No. 6)

boiling between 445 ‘C and zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA541 3 C were used. The HVGO was used as a “base

147

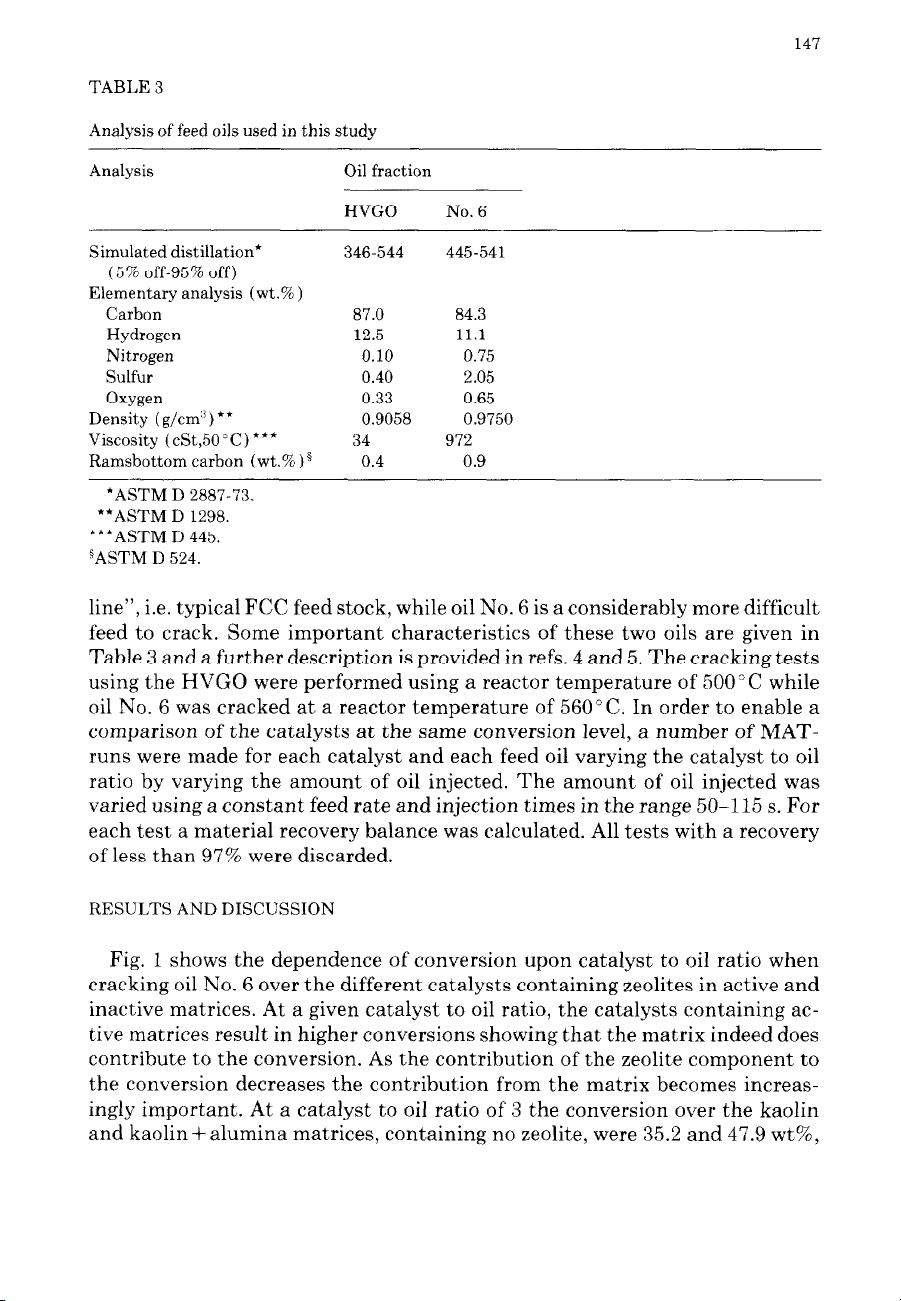

TABLE 3

Analysis of feed oils used in this study

Analysis Oil fraction

HVGO No. 6

Simulated distillation*

(5% off-95% off)

Elementary analysis (wt.% )

Carbon

Hydrogen

Nitrogen

Sulfur

Oxygen

Density (g/cm”) **

Viscosity (cSt,SO’C) ***

Ramsbottom carbon (wt.% ) g

346-544 445-541

87.0 84.3

12.5 11.1

0.10 0.75

0.40 2.05

0.33 0.65

0.9058 0.9750

34 972

0.4 0.9

*ASTM D 2887-73.

**ASTM D 1298.

***ASTM D 445.

“ASTM D 524.

line”, i.e. typical FCC feed stock, while oil No. 6 is a considerably more difficult

feed to crack. Some important characteristics of these two oils are given in

Table 3 and a further description is provided in refs. 4 and 5. The cracking tests

using the HVGO were performed using a reactor temperature of 500°C while

oil No. 6 was cracked at a reactor temperature of 560°C. In order to enable a

comparison of the catalysts at the same conversion level, a number of MAT-

runs were made for each catalyst and each feed oil varying the catalyst to oil

ratio by varying the amount of oil injected. The amount of oil injected was

varied using a constant feed rate and injection times in the range 50-115 s. For

each test a material recovery balance was calculated. All tests with a recovery

of less than 97% were discarded.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Fig. 1 shows the dependence of conversion upon catalyst to oil ratio when

cracking oil No. 6 over the different catalysts containing zeolites in active and

inactive matrices. At a given catalyst to oil ratio, the catalysts containing ac-

tive matrices result in higher conversions showing that the matrix indeed does

contribute to the conversion. As the contribution of the zeolite component to

the conversion decreases the contribution from the matrix becomes increas-

ingly important. At a catalyst to oil ratio of 3 the conversion over the kaolin

and kaolin+alumina matrices, containing no zeolite, were 35.2 and 47.9 wt%,