Genome Biology 2008, 9:R67

Open Access

20 0 8Ruotoloet al.Volume 9, Issue 4, Article R67

Research

Membrane transporters and protein traffic networks differentially

affecting metal tolerance: a genomic phenotyping study in yeast

Roberta Ruotolo, Gessica Marchini and Simone Ottonello

Address: Department of Biochem istry and Molecular Biology, Viale G.P. Usberti 23/ A, University of Parma, I-4310 0 Parma, Italy.

Correspondence: Sim one Ottonello. Email: s.ottonello@unipr.it

© 2008 Ruotolo et al.; licensee BioMed Central Ltd.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Metal tolerance in yeast<p>Genomic phenotyping was used to assess the role of all non-essential S. cerevisiae proteins in modulating cell viability after exposure to cadm ium , nickel an d other m etals.</ p>

Abstract

Background: The cellular mechanisms that underlie metal toxicity and detoxification are rather

variegated and incompletely understood. Genomic phenotyping was used to assess the roles played

by all nonessential Saccharomyces cerevisiae proteins in modulating cell viability after exposure to

cadmium, nickel, and other metals.

Results: A number of novel genes and pathways that affect multimetal as well as metal-specific

tolerance were discovered. Although the vacuole emerged as a major hot spot for metal

detoxification, we also identified a number of pathways that play a more general, less direct role in

promoting cell survival under stress conditions (for example, mRNA decay, nucleocytoplasmic

transport, and iron acquisition) as well as proteins that are more proximally related to metal

damage prevention or repair. Most prominent among the latter are various nutrient transporters

previously not associated with metal toxicity. A strikingly differential effect was observed for a large

set of deletions, the majority of which centered on the ESCRT (endosomal sorting complexes

required for transport) and retromer complexes, which - by affecting transporter downregulation

and intracellular protein traffic - cause cadmium sensitivity but nickel resistance.

Conclusion: The data show that a previously underestimated variety of pathways are involved in

cadmium and nickel tolerance in eukaryotic cells. As revealed by comparison with five additional

metals, there is a good correlation between the chemical properties and the cellular toxicity

signatures of various metals. However, many conserved pathways centered on membrane

transporters and protein traffic affect cell viability with a surprisingly high degree of metal

specificity.

Background

Metals, especially the nonessential ones, are a major environ-

mental and hum an health hazard. The m olecular bases of

their toxicity as well as the m echanisms that cells have

evolved to cope with them are rather variegated and incom -

pletely understood. The soft acid cadm ium and the borderline

acid nickel are nonessential transition metals of great envi-

ronmental concern . Although redox inactive, cadmium and

nickel cause oxidative dam age indirectly [1] and they both

have carcinogenic effects [2,3], albeit with reportedly differ-

ent m echanisms [1,4-6].

Published: 7 April 2008

Genome Biology 2008, 9:R67 (doi:10.1186/gb-2008-9-4-r67)

Received: 29 December 2007

Revised: 26 February 2008

Accepted: 7 April 2008

The electronic version of this article is the complete one and can be

found online at http://genomebiology.com/2008/9/4/R67

Genome Biology 2008, 9:R67

http://genomebiology.com/2008/9/4/R67 Genome Biology 2008, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article R67 Ruotolo et al. R67.2

The cellular effects of cadmium are far more studied than

those of nickel. In strum en tal to the elucidation of some of the

basic mechanisms that underlie cadm ium toxicity has been

the model eukaryote Saccharom yces cerevisiae [7]. It was

studies conducted in this organism , for example, that yielded

the first dem onstration of the indirect nature of cadmium's

genotoxic effects, which leads to gen om e instability by inhib-

itin g DNA mism atch repair [8] and other DNA repair systems

[6]. Sim ilarly, lipid peroxidation as a major mechanism of

cadmium toxicity [9] as well as the central roles played by

thioredoxin and reduced glutathion e (GSH ) [7], and vacuolar

tran sport system s such as Ycf1 [10], in cadm ium detoxifica-

tion were first documented in yeast. Som e of the above com-

ponents were sh own to be upregulated at both the mRNA

[11,12] an d protein [12,13] levels in cadm ium-stressed yeast

cells. Predom inant among these expression changes was the

upregulation of the sulfur amino acid biosynthetic pathway

an d the in duction of isozymes with a markedly reduced sulfur

am ino acid con tent as a way to spare sulfur for GSH synthesis

[12]. A num ber of addition al cadmium -responsive gen es

without any obvious relationship to sulfur sparing or cad-

mium stress were also iden tified, however. Curiously, only a

sm all subset of the most cadm ium-responsive genes produce

a m etal-sensitive phen otype when deleted [13], thus reinforc-

ing the notion that transcription al modulation per se is not a

general predictor of the pathways influen cing stress tolerance

[14,15]. For exam ple, deletion of genes coding for two major

organic peroxide-scavengin g en zymes (GPX3 and AHP1; the

latter en coding a cadmium -induced alkyl hydroperoxide

reductase) did not im pair cadmium tolerance [13].

By comparison, only a few studies have dealt with nickel tox-

icity in yeast. Interestingly, they showed that un programm ed

gene silencing, which is a m ajor mechanism of nickel toxicity

an d carcinogenicity in hum ans [16,17], also operates in S. cer-

evisiae. This further em phasizes the high degree of con serva-

tion of various aspects of metal toxicity as well as the

usefulness of S. cerevisiae as a model organism for elucidat-

ing the corresponding pathways in human s. They also sug-

gest, however, that a broad and as yet largely unexplored

range of cellular pathways m ay be involved in alleviating the

toxic effects of metals. What is currently missing, in particu-

lar, is a global view of such pathways at the phen otype level

an d a genome-wide com parison of differen t metals as well as

other stressors.

We have addressed these issues by examining the fitness of a

genome-wide collection of yeast deletion mutant strains

[18 ,19] exposed to two chemically diverse metals, namely

cadmium and nickel, each of which is a known carcinogen

[2,3,20]. This allowed us to assess the role of all nonessential

protein s in m odulating the cellular toxicity (sensitivity or

resistance) of these two metals. The results of this screen were

integrated with interactom e data and com pared with the

genomic phenotyping profiles of other stressors. To gain fur-

ther insight into the cytotoxicity signatures of different met-

als, the entire set of 38 8 mutants exhibitin g an altered

viability after exposure to cadmium and nickel was chal-

lenged with four additional metals (mercury, zin c, cobalt an d

iron) plus the m etalloid AsO2-. Although overall there is good

correlation between the chemical properties and the cellular

toxicity sign atures of various metals, many conserved path-

ways cen tered on (bu t not lim ited to) m em brane transporters

an d protein traffic affect cell viability with a surprisin gly high

degree of metal specificity.

Results and discussion

Genomic phenotyping of cadmium and nickel toxicity

Sublethal concentrations of 50 μmol/ l cadmium an d 2.5

mmol/ l nickel (see 'Materials an d methods', below, for

details) were used for multireplicate screening of the yeast

haploid deletion mutan t collection (five replicates for each

metal), which was perform ed by manually pinning ordered

sets of 38 4 strains onto metal-containing yeast extract-pep-

tone-dextrose (YPD)-agar plates (Additional data file 1 [Fig-

ure S1A]). After culture and colony size inspection, strain s

scored as metal sensitive or resistan t in at least three screens

were individually verified by spotting serial dilutions onto

metal-containing plates. Mutant strains exhibiting various

levels of metal sensitivity (high sen sitivity [H S], medium sen-

sitivity [MS], and low sen sitivity [LS]) and a single class of

metal resistant mutant strains were recognized (Additional

data file 1 [Figures S1B and S1C]).

A total of 388 mutan t strains that were sensitive or resistant

to cadmium and/ or nickel were identified. As shown in Figure

1a, some of them were specifically sensitive or resistant to

cadmium or nickel, whereas others exhibited an altered toler-

an ce to both metals. Metal-sensitive mutants exceeded the

resistant ones by more than threefold. The num ber of sensi-

tive m utants was considerably higher for cadmium than for

nickel, which is in accordance with the strikingly different cel-

lular toxicity previously reported for these two metal ion s in

an imal cells [4,21]. Con versely, m utants resistan t to nickel

were significantly more abundant than cadmium-resistant

mutant strain s. More than two-thirds of the nickel-resistant

mutan ts were foun d to be sen sitive to cadmium, as opposed

to on ly one in stance of cadmium resistance/ nickel sensitivity

(sm f1

Δ

). A detailed list of the mutants, in cluding their degree

of sensitivity (Addition al data file 1 [Figures S1B and S1C]),

Gene Ontology (GO) description, and related inform ation, is

provided in Additional data file 2. Hum an orthologs were

iden tified for about 50% of the genes causin g m etal sen sitivity

or resistance, 27 of which correspond to genes previously

found to be involved in human diseases, especially cancer.

Twenty-four mutants are deleted in genes en coding unchar-

acterized open reading frames (ORFs), whereas four metal

toxicity modulating gen es are homologous to un ann otated

hum an ORFs (Additional data file 2). Gen om ic phenotyping

data were also compared with the results of transcriptomic

http://genomebiology.com/2008/9/4/R67 Genome Biology 2008, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article R67 Ruotolo et al. R67.3

Genome Biology 2008, 9:R67

an alyses conducted on cadmium -treated yeast cells [11]. In

keeping with previous comparisons of this kind [14,15], only

a m arginal (about 7%) overlap was detected (Additional data

file 2).

As revealed by the GO analysis summarized in Figure 1b, a

wide range of cellular processes is engaged in the modulation

of cadmium and nickel toxicity. At variance with cadmium

resistant mutants, which are scattered throughout various

GO categories, nickel-resistant as well as cadmium / nickel-

sensitive mutant strains were found to be en riched in specific

functional categories. Som e of the top responsive genes iden-

tified by previous expression profiling studies (for example,

genes in volved in GSH and reduced sulfur metabolism

[11,13]) were foun d to be am on g deletion mutan ts specifically

sensitive to cadmium, especially within the 'response to

stress' category. As expected for cells treated with agents that

are actively internalized by and sequestered into vacuoles, a

num ber of the m ost significant GO categories are related to

'transport', particularly to the vacuole, and to the biogenesis

an d functioning (for example, acidification) of this organ elle.

Several processes not so obviously associated with metal tol-

erance were also identified. For exam ple, 'nucleocytoplasm ic

transport' (including nuclear pore com plex formation, and

function ality) em erged as a process that is specifically

im paired in nickel-sensitive m utants. Other processes cen-

tered on vesicle-mediated transport also profoundly influ-

ence cadmium and nickel tolerance in different, often

contrasting ways. For example, many 'Golgi-to-vacuole trans-

port' mutants appear to be sensitive to both cadmium and

Distribution among different sensitivity/resistance groups and functional classification of metal tolerance affecting mutationsFigure 1

Distribution among different sensitivity/resistance groups and functional classification of metal tolerance affecting mutations. (a) Venn diagram visualization

of mutant strains displaying multimetal or metal-specific sensitivity (green circles) or resistance (red circles); also shown are mutants characterized by an

opposite phenotypic response to the two metals (45 cadmium sensitive/nickel resistant strains and one cadmium resistant/nickel sensitive strain). (b)

Biologic processes associated with metal toxicity-modulating genes identified with the Gene Ontology (GO) Term Finder program [99]. Statistical

significance of GO term/gene group association (P-value < 0.001) and enrichment ratios are reported for each category; parent terms are presented in

bold, and child terms of the parent class 'transport' are presented in italics.

Enrichment ratio P-value Enrichment ratio P-value Enrichment ratio P-value

transport

2.5 1.63E-16 2.7 1.10E-07 3.9 1.91E-12

vacuolar transport

8.1 3.18E-24 6.8 1.70E-05 19.4 4.67E-21

vesicle-mediated transport

4.3 1.31E-19 3.6 0.00068 6.6 6.97E-10

post-Golgi vesicle-mediated transport

6.1 2.05E-06 11.2 4.77E-07

Golgi to vacuole transport

9.7 0.00026 22.3 1.36E-06

vacuole organization and biogenesis

9.8 2.07E-17 23.3 8.28E-26

vacuolar acidification

17.3 3.44E-14 47.7 2.33E-23

cation homeostasis

5.8 2.10E-10 13.2 9.74E-17

telomere organization and biogenesis

5.1 1.94E-24 4.4 9.53E-06

response to chemical stimulus

3.1 2.94E-10 3.5 0.0001

endosome transport

13.4 1.94E-25 34.1 1.05E-20

ubiquitin-dependent protein catabolic process

via the multivesicular bod

y

p

athwa

y

19.5 9.61E-12 77.5 1.67E-17

protein targeting to vacuole

6.8 3.76E-10 18.3 2.63E-11

protein retention in Golgi

9.7 3.83E-05 37.7 2.35E-09

retrograde transport, endosome to Golgi

18.0 5.72E-09 35.0 0.00016

post-translational protein modification

3.0 1.53E-09

covalent chromatin modification

5.2 4.62E-06

Golgi vesicle transport

3.4 9.01E-05

response to stress

2.4 5.75E-06

transcription, DNA-dependent

2.1 1.41E-05

nucleocytoplasmic transport

4.7 6.60E-04

RNA export from nucleus

6.9 5.85E-05

tnatsiser-iNevitis

n

es-iNevit

i

snes

-

dC

GO functional categories

(a)

(b)

79 38179

15

11

45

20

Cd-sensitive

(303)

Ni-sensitive

(118)

Cd-resistant

(36)

Ni-resistant

(71)

1

Genome Biology 2008, 9:R67

http://genomebiology.com/2008/9/4/R67 Genome Biology 2008, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article R67 Ruotolo et al. R67.4

nickel, whereas defects in 'endosome transport' and

'retrograde transport en dosome-to-Golgi' render cells sensi-

tive to cadmium but resistant to nickel (see below).

Im portantly, mutants with metal sen sitivity phenotypes of

varying severity (Additional data files 1 and 2) are present

within differen t mutant classes as well as function al catego-

ries. This discounts the possibility that only highly sensitive

mutant strains or particular classes of genes are relevant to

cadmium / nickel tolerance, an d suggests that a suite of path-

ways, m uch broader than previously thought, modulates

metal tolerance in eukaryotic cells.

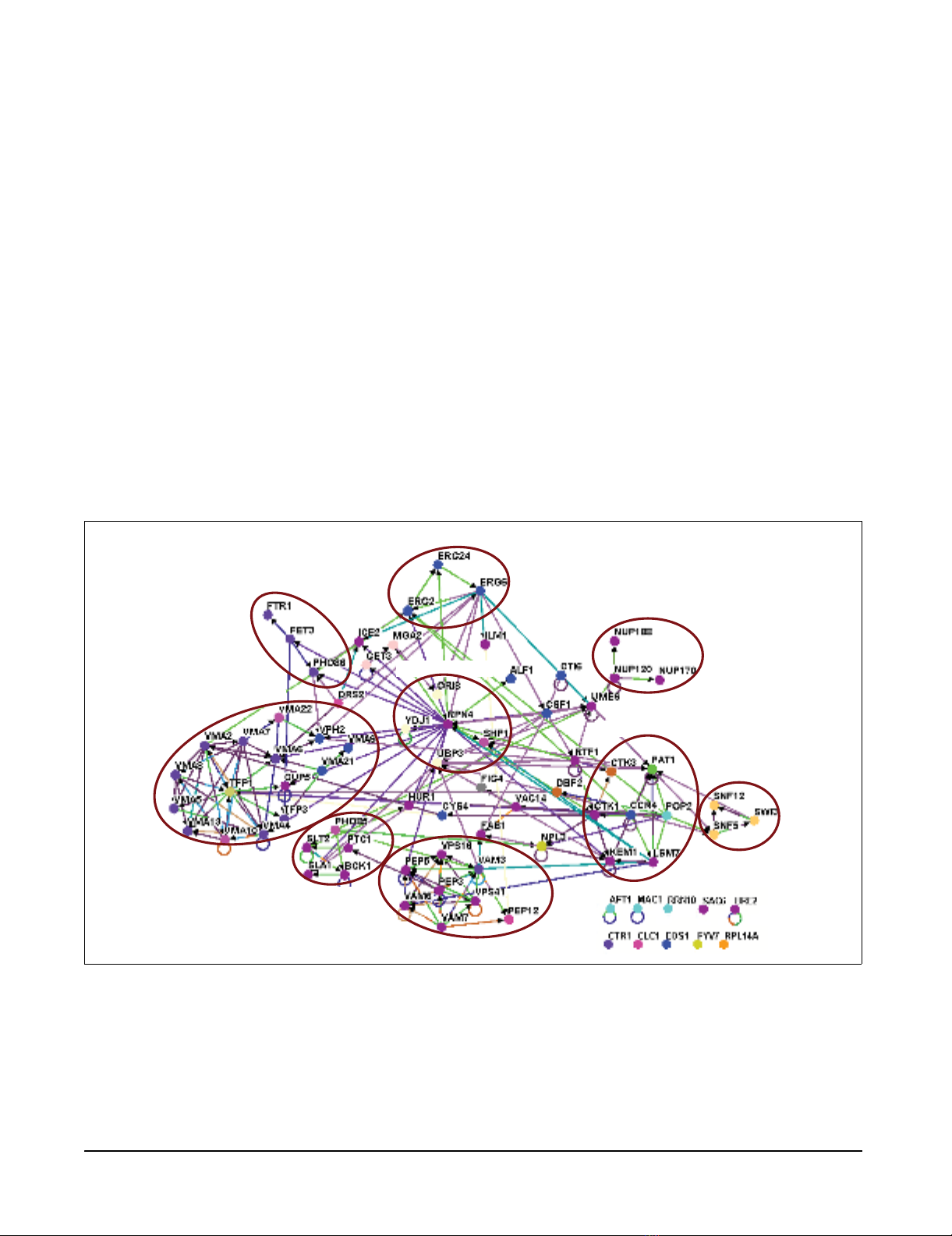

Mutations impairing cadmium and nickel tolerance

To gain a m ore detailed understanding of metal toxicity-m od-

ulatin g pathways and the way in which they are in tercon-

nected, we set out to an alyze genom e phenotypin g data in the

fram ework of the known yeast interactom e [22-24]. The 79

genes that when mutated cause sensitivity to both cadmium

an d nickel were initially addressed. As shown in Figure 2, 52

of these genes were iden tified as part of nine functional sub-

networks (a minim um of three gene products sharing at least

one GO biological process annotation and connected by at

least two physical or genetic interactions; see 'Materials an d

methods', below, for details on this analysis). Seventeen of the

rem aining genes could be traced to a particular subnetwork

but did not pass the above criterion , whereas the other ten

rem ained as 'solitary' entries. Metal sensitivity phen otypes

for at least two deletion mutan ts random ly sampled from

each subnetwork were confirmed by independent serial dilu-

tion assays carried out on untagged strains of the opposite

mating type (data not shown).

In accordance with the tight relationship between metal tol-

erance and vacuole function ality highlighted by GO analysis,

the most populated subnetwork (subnetwork 1; P-value < 1.5

× 10 -18 ) comprises a large set of subunits, assembly factors,

an d regulators of V-ATPase, which is the enzyme responsible

for generating the electrochem ical poten tial that drives the

Interaction subnetworks among gene products whose disruption causes cadmium/nickel sensitivityFigure 2

Interaction subnetworks among gene products whose disruption causes cadmium/nickel sensitivity. Physical (110) and genetic (105) interactions were

identified computationally using the Network Visualization System Osprey [103]. Gene products are represented as nodes, shown as filled circles colored

according to their Gene Ontology (GO) classification; interactions are represented as node-connecting edges, shown as lines, colored according to the

type of experimental approach utilized to document interaction as specified in the BioGRID database [22] and in the Osprey reference manual. The nine

identified subnetworks (a minimum of three interacting gene products sharing at least one GO biologic process annotation and connected by at least two

physical or genetic interactions; see 'Materials and methods') are encircled and associated with a general function descriptor. Thirteen interacting gene

products whose interaction or functional similarity features do not satisfy the above criterion are shown outside encircled subnetworks; genes without any

reported interaction (or linked via essential genes, not addressed in this study) are shown at the bottom. Individual subnetworks were subjected to

independent verification by serial dilution growth assays carried on at least two untagged strains of the opposite mating type (see 'Materials and methods').

sn., subnetwork.

Vacuole fusion (sn. 2)

Proteasome (sn. 3)

Chromatin remodelling (sn. 4)

Nuclear pore complex (sn. 7)

ERG pathway (sn. 8)

Essential ion homeostasis (sn. 9)

CCR4 & other mRNA processing enzymes (sn. 6)

V-ATPase assembly/regulation (sn. 1)

Cell wall integrity pathway (sn. 5)

http://genomebiology.com/2008/9/4/R67 Genome Biology 2008, Volume 9, Issue 4, Article R67 Ruotolo et al. R67.5

Genome Biology 2008, 9:R67

active accum ulation of various ion s within the vacuole [25].

Also related to V-ATPase functionality (although not in cluded

in subnetwork 1) is Cys4, which is the first enzyme of cysteine

biosynthesis, whose disruption in directly interferes with vac-

uolar H+-ATPase activity [26]. An other highly populated sub-

network (subn etwork 2; P-value < 2 × 10 -5) contains eight

additional vacuole-related genes belongin g to either class B or

C 'vacuolar protein sorting' (vps) mutants, whose deletion

respectively causes a fragm en ted vacuole m orphology or lack

of any vacuole-like structure [27,28]. This indicates that

defects in specific aspects of vacuole functionality as well as in

late steps of vesicle transport to, an d fusion with, the vacuole

cause sen sitivity to both m etal ions. In keeping with this view,

three additional proteins (Fab1, Fig4, and Vac14), which also

cause cadmium / nickel sen sitivity when disrupted, con trol

trafficking to the vacuolar lumen [29,30]. The role played by

the vacuole in metal toxicity modulation may entail both

metal sequestration within this organ elle as well as the clear-

an ce of metal-damaged macrom olecules.

Connected with these vacuole-related hot spots, which

include a num ber of genes previously associated with cad-

mium (but not nickel) tolerance [7], are five additional sub-

networks. One of them (subnetwork 3; P-value < 7 × 10 -2)

com prises the master regulator Rpn4, which is required for

proteasom e biogenesis, an d three ubiquitin-related proteaso-

mal components (Qri8 , Shp1, an d Ubp3), thus reinforcing the

notion that abnormal protein degradation plays an im portant

role in toxic metal tolerance [31-33]. Other components pre-

viously associated with tolerance to cadm ium an d to other

stressors include three subunits of the chromatin rem odeling

com plex SWI/ SNF (SWItch/ Sucrose NonFerm enting; sub-

network 4; P-value < 0.1) [34] and a group of regulators of the

cell wall integrity/ m itogen-activated protein kinase signaling

pathway (subn etwork 5; P-value < 3.4 × 10-6) [35,36]. These

are functionally linked to the secon d largest subnetwork (sub-

network 6; P-value < 9.1 × 10 -5), which is centered on Ccr4

an d its associated proteins. Ccr4 is a multifunctional mRNA

deadenylase that can be part of mRNA decay as well as tran -

scriptional regulatory complexes in association with the NOT

factors [37]. Non e of the NOT deletion mutan ts was identified

as metal sen sitive, whereas a few other transcriptional regu-

lators interacting with Ccr4 (for example, Dbf2 and Rtf1)

cause cadmium / nickel sen sitivity when disrupted. Pop2,

an other major deadenylase in S. cerevisiae [37], along with

three additional RNA processin g enzymes (Kem 1, Lsm7, and

Pat1), were also found am ong cadmium/ nickel sensitive

mutants. Previously known to be involved in the response to

DNA damaging agents [38], these proteins thus appear to

play a role also in metal toleran ce, which might be aim ed at

ensuring proper tran slational/ m etabolic reprogramm ing

under stress condition s. This finding, along with the identifi-

cation of cadmium / nickel-sensitive m utations affecting three

nuclear pore com plex subunits (subnetwork 7; P-value < 7.3

× 10-4) and a mRNA export factor (Npl3), points to mRNA

decay and trafficking (particularly nuclear export) as a novel

hot spot of metal toxicity.

The last two subnetworks pertain to ergosterol biosynthesis

(subnetwork 8; P-value < 9.8 × 10 -4), which critically influ-

ences the structural and function al integrity of the plasma

membran e (Additional data file 1 [Figure S1B] shows a repre-

sentative phen otype), and to essen tial ion hom eostasis (sub-

network 9; P-value < 0 .12). The latter includes the

endoplasmic reticulum exit protein Pho86, which is required

for plasma m em brane translocation of the Pho84 phosphate

transporter, the high-affinity iron transport com plex Ftr1/

Fet3, and a transcription factor (encoded by the solitary gene

AFT1) that positively regulates FTR1/FET3 expression. All

these genes cause cadm ium/ n ickel sensitivity when m utated.

A possible explanation for this finding is that toxic metals can

make iron , an d other essential ions, lim iting for cell growth

(see below). In fact, on e copper transporter (Ctr1) and a

copper uptake-related transcription factor (Mac1) were also

found among the cadmium / nickel-sensitive mutants in our

screen.

Metal-specific sensitive mutants

A similar interactom e analysis was applied to deletion

mutants that proved to be specifically sensitive to nickel or

cadmium . As shown in Table 1 (an d Additional data files 3

an d 4), this led to the identification of seven m etal-specific

subnetworks and to the inclusion of nickel and cadm ium spe-

cific mutants into previously iden tified subnetworks. Espe-

cially noteworthy are the nickel-specific expansion of the

nuclear pore com plex (subnetwork 7; P-value < 1 × 10 -4) and

the many cadmium -specific mutants added to subnetwork 4

(P-value < 1.7 × 10 -3), which includes various com ponents of

the chrom atin modification com plexes SAGA and INO80 ,

plus the histon e deacetylase HDA1. Proteins in volved in his-

tone acetylation may affect metal toleran ce by in fluencing

DNA reactivity as well as DNA accessibility to repair enzymes,

or by influencing the expression of genes needed for recovery.

The selective enrichm en t of cadm ium -sensitive mutants

within this subn etwork (as well as in the cadmium -specific

subnetwork 'DNA repair'; subnetwork 12; see below) is not

too surprising, if on e considers the known gen otoxic effects of

cadmium , caused by in terference with DNA repair [6,8].

Only one of the new subnetworks (subnetwork 10 ; P-value <

1.6 × 10 -3) was foun d to be specifically associated with nickel

sensitivity (Table 1 and Addition al data file 3). This includes

various components of a m ultiprotein complex (Adaptor Pro-

tein com plex AP-3) that is in volved in the alkalin e phos-

phatase (ALP) path way for protein transport from the Golgi

to the vacuole. At variance with the other Golgi-to-vacuole

transport route (the so-called 'carboxypeptidase Y' [CPY]

pathway), which proceeds through an endosom e interm edi-

ate and includes a num ber of compon ents that when dis-

rupted cause cadm ium sensitivity (see subnetwork 15 in Table

1), the ALP pathway directly targets its cargo proteins to the

![Vaccine và ứng dụng: Bài tiểu luận [chuẩn SEO]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2016/20160519/3008140018/135x160/652005293.jpg)