N-Glycosylation is important for the correct intracellular

localization of HFE and its ability to decrease cell surface

transferrin binding

Lavinia Bhatt

1

, Claire Murphy

2

, Liam S.O’Driscoll

2

, Maria Carmo-Fonseca

3

, Mary W. McCaffrey

1

and John V. Fleming

2,3

1 Department of Biochemistry, Biosciences Institute, University College Cork, Ireland

2 Department of Biochemistry, School of Pharmacy and ABCRF, University College Cork, Ireland

3 Institute of Molecular Medicine, University of Lisbon, Portugal

Keywords

HFE; N-glycosylation; transferrin; transferrin

receptor 1; b2-microglobulin

Correspondence

J. V. Fleming, Department of Biochemistry

and School of Pharmacy, University College

Cork, Cork, Ireland

Fax: +353 21 4901656

Tel: +353 21 4901679

E-mail: j.fleming@ucc.ie

Note

L. Bhatt and C. Murphy contributed equally

to this work

(Received 8 February 2010, revised 14 May

2010, accepted 2 June 2010)

doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07727.x

HFE is a type 1 transmembrane protein that becomes N-glycosylated dur-

ing transport to the cell membrane. It influences cellular iron concentra-

tions through multiple mechanisms, including regulation of transferrin

binding to transferrin receptors. The importance of glycosylation in HFE

localization and function has not yet been studied. Here we employed bio-

informatics to identify putative N-glycosylation sites at residues N110,

N130 and N234 of the human HFE protein, and used site-directed muta-

genesis to create combinations of single, double or triple mutants. Com-

pared with the wild-type protein, which co-localizes with the type 1

transferrin receptor in the endosomal recycling compartment and on dis-

tributed punctae, the triple mutant co-localized with BiP in the endoplas-

mic reticulum. This was similar to the localization pattern described

previously for the misfolding HFE-C282Y mutant that causes type 1 hered-

itary haemachromatosis. We also observed that the triple mutant was func-

tionally deficient in b2-microglobulin interactions and incapable of

regulating transferrin binding, once again, reminiscent of the HFE-C282Y

variant. Single and double mutants that undergo limited glycosylation

appeared to have a mixed phenotype, with characteristics primarily of the

wild-type, but also some from the glycosylation-deficient protein. There-

fore, although they displayed an endosomal recycling compartment/punc-

tate localization like the wild-type protein, many cells simultaneously

displayed additional reticular localization. Furthermore, although the

majority of cells expressing these single and double mutants showed

decreased surface binding of transferrin, a number appeared to have lost

this ability. We conclude that glycosylation is important for the normal

intracellular trafficking and functional activity of HFE.

Structured digital abstract

lMINT-7896236,MINT-7896218:beta2M (uniprotkb:P61769)physically interacts (MI:0915)

with HFE (uniprotkb:Q30201)byanti bait coimmunoprecipitation (MI:0006)

lMINT-7896162:TfR1 (uniprotkb:P02786) and HFE (uniprotkb:Q30201)colocalize (MI:0403)

by fluorescence microscopy (MI:0416)

Abbreviations

ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ERC, endosomal recycling compartment; HH, hereditary haemachromatosis; b2M, b2 microglobulin; MHC, major

histocompatability complex; PNGase F, N-glycosidase F; Tfn, transferrin; TfR1, transferrin receptor 1; TfR2, transferrin receptor 2.

FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 3219–3234 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS 3219

Introduction

The hereditary haemochromatosis (HH) protein HFE

(high Fe) is a type 1 transmembrane protein that plays

an important role in controlling physiological iron

homeostasis [1–3]. It is widely expressed throughout

the body with expression highest in cells that are

involved in iron metabolism [4–6]. Mutations in the

HFE protein cause type 1 HH, which is an inherited

disease of iron metabolism that results in iron overload

in several organs [4,7]. The HFE mutation detected in

the majority of HH patients results in the replacement

of cysteine residue 282 with tyrosine (C282Y). The

mutant protein is unable to form a structurally impor-

tant disulfide bridge required for HFE interactions

with b2 microglobulin (b2M) [4,5,8–11]. In the absence

of b2M binding, the protein misfolds and is retained in

the endosplasmic reticulum (ER) where it induces an

unfolded protein stress response that is characterized

by alternative splicing of XBP-1 and increased expres-

sion of CHOP and BiP [12–14]. A second well-

described HFE mutation associated with HH leads to

the replacement of histidine at residue 63 with aspar-

tate. This mutant is capable of b2M interaction and

cell-surface expression but is unable to regulate cellular

iron uptake like the wild-type HFE protein [4,15].

Although much insight into HFE function has been

gained through studying the cellular and biochemical

properties of these different mutant proteins, the exact

mechanism by which HFE regulates intracellular iron

levels is still not completely understood.

The HFE primary sequence exhibits significant

homology to major histocompatability complex

(MHC) class I molecules and the protein is organized

into a1, a2 and a3 structural domains that resemble

those described for MHC class I and related proteins

[4,16]. The N-terminal a1 and a2 domains come

together to form a superstructure composed of two

ahelices layered on top of eight anti-parallel bsheets.

In MHC class I proteins this a1/a2 superstructure

forms a peptide-binding groove that mediates antigen

binding and presentation to CD8

+

cytolytic T cells.

In HFE, the proximity of the two ahelices and the

presence of amino acid side chains that project into

the groove appear to prevent peptide binding [16]. The

a3 region, like its homologous domain in MHC

class I, is an immunoglobulin-like domain that medi-

ates binding to b2M [16,17]. C-Terminal residues of

HFE mediate its retention in the cell membrane.

Shortly after HFE was discovered it was reported to

co-localize and interact with the type 1 transferrin

receptor (TfR1) [5,18]. TfR1 mediates the endocytosis

of iron-loaded transferrin into acidic endosomes where

the iron is released and transported into the cytoplasm

via the Nramp2-DCT1 iron transporter. Apo-transfer-

rin and TfR1 are recycled to the cell surface where

apo-transferrin is released [3,19]. Crystallography stud-

ies suggest that the a3 stem of HFE lies parallel to the

cell membrane and that the a1/a2 superstructure inter-

acts with helical regions located within TfR1. In this

way, it is possible for two HFE proteins to be posi-

tioned at either side of the TfR1 homodimer and form

a tetrameric complex that exhibits twofold symmetry

[17]. Reports from crystallography experiments have

been supported by mutagenesis studies that identified

residues located at the end of an a-helical region of the

HFE a1 domain (V100 and W103A) as being of par-

ticular importance for TfR1 interactions [16,17,20].

The effect of HFE binding to TfR1 is to lower the

affinity of the receptor for transferrin [15]. This most

likely reflects the existence of overlapping HFE and

transferrin-binding sites on the receptor [21,22]. Suc-

cessive studies indicate that HFE and TfR1 co-localize

during endosomal trafficking, although there are con-

tradictory reports as to whether TfR1 recycling is

affected by HFE [23–29].

Despite these well-described interactions, there is

mounting evidence that HFE regulation of cellular

iron levels may not depend solely on TfR1 binding

[30,31]. Attention has shifted to a second transferrin

receptor, TfR2, whose pattern of expression is more

restricted than that of ubiquitously expressed TfR1

[32]. Levels of TfR2 are highest in hepatocytes, the

predominant site of HFE expression, and recent stud-

ies have confirmed that the two proteins are capable of

interacting [33,34]. The nature of these interactions dif-

fers from those observed between HFE and TfR1 in

that they are mediated by the a3 domain of HFE, as

opposed to the a1/a2 superstructure [33]. An emerging

model, therefore, is that TfR2 competes with TfR1 for

lMINT-7896258,MINT-7896317,MINT-7896330,MINT-7896348,MINT-7896366:HFE (uni

protkb:Q30201) and transferrin (uniprotkb:P02787)colocalize (MI:0403)byfluorescence

microscopy (MI:0416)

lMINT-7896149:HFE (uniprotkb:Q30201) and BiP (uniprotkb:P11021)colocalize (MI:0403)

by fluorescence microscopy (MI:0416)

N-Glycosylation of HFE L. Bhatt et al.

3220 FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 3219–3234 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS

HFE binding. This occurs maximally at high concen-

trations of transferrin. The resulting HFE–TfR2 com-

plex, which is stabilized at high iron concentrations, is

believed to somehow regulate the expression of other

genes involved in iron metabolism. This includes hepci-

din, a 25 amino acid antimicrobial peptide that is

expressed in liver cells and is now recognized as a key

regulator of iron homeostasis in the body. Hepatocel-

lular hepcidin mRNA levels have been shown to be

regulated by HFE, and are altered in haemachromato-

sis patients with the C282Y mutation [35–37].

The importance of N-glycosylation with respect to

protein expression and function is highly variable.

Roles have been described in the secretion, stability

and oligomerization of proteins [38,39], the bioactivi-

ties of enzymes [40] and the binding affinities of

ligands and receptors [41]. In many instances, specific

functions can be attributed to glycosylation at specific

sites. For example, the human gonadotropin asubunit

has N-glycosylation sites at residues Asn52 and Asn78

that have been shown to differentially regulate receptor

signalling and secretion, respectively [38,39]. Another

example is the type 1 transferrin receptor, which has

N-glycosylation sites at residues Asn251, Asn317 and

Asn727. Mutation of Asn727 decreases cell-surface

expression, whereas mutation at the other two sites

does not [42].

HFE becomes glycosylated during post-translational

processing. Transfection studies have confirmed that

this involves N-glycosylation, and incubation of lysates

from HFE-expressing cells with N-glycosidase F

(PNGase F) leads to the accumulation of lower molec-

ular mass HFE proteins [13,43]. The carbohydrate

moiety undergoes processing and endoglycosi-

dase H-resistant HFE isoforms can be detected by

30 min post translation [10,13,18,23]. Although these

studies demonstrate that HFE is glycosylated, the

specific role, if any, that glycosylation might play in

cellular HFE function has not previously been studied.

In this article, we map the sites of HFE N-glycosyla-

tion and examine the importance of glycosylation on

parameters of protein localization and function.

Results

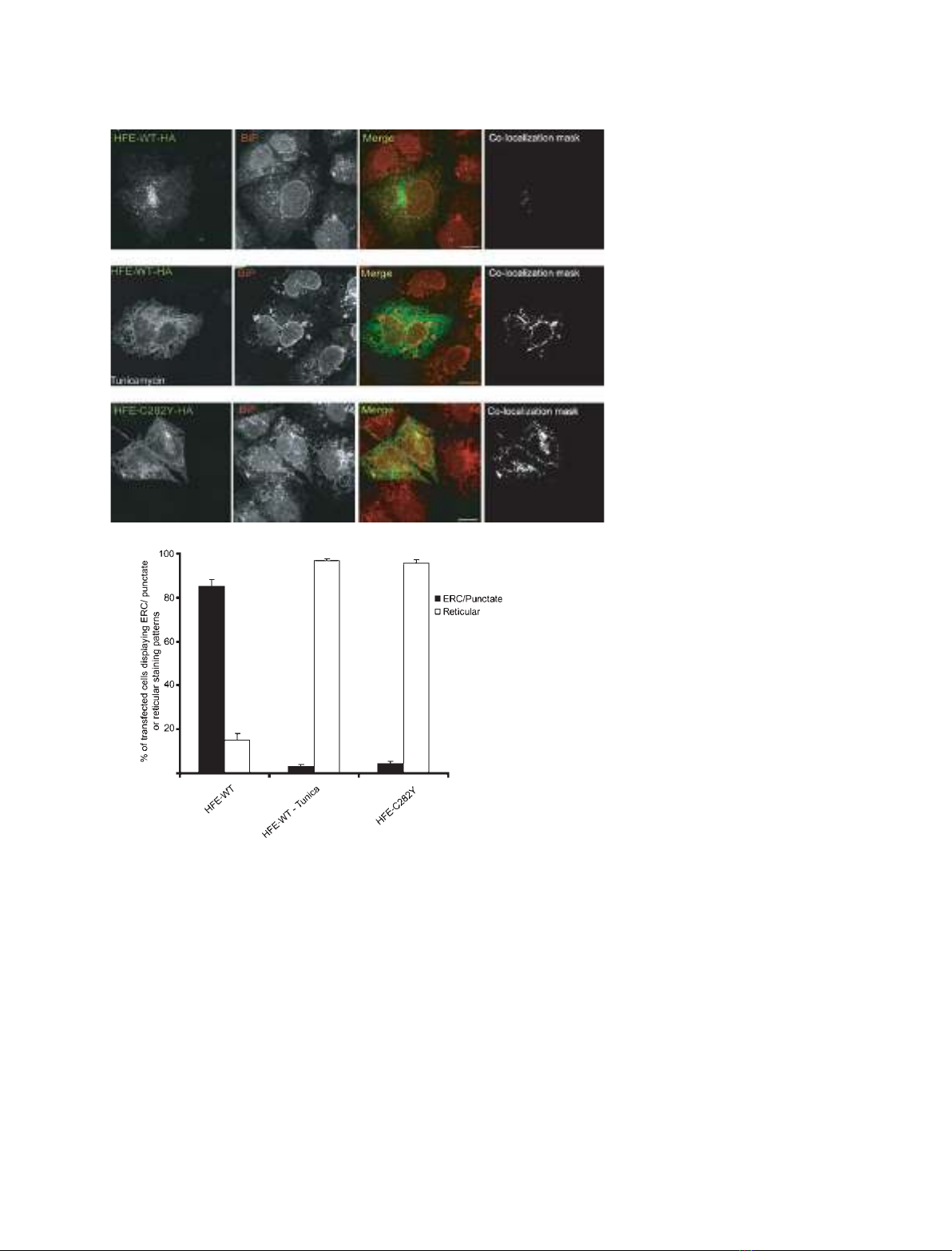

Tunicamycin treatment results in a reticular

pattern of HFE localization

Previous studies have demonstrated that HFE under-

goes post-translational N-glycosylation. As a first step

towards assessing the importance of N-glycosylation

on HFE expression, we transiently transfected HuTu80

to express HFE-WT–HA and cultured the cells in the

presence or absence of tunicamycin to inhibit glycan

production. Control, untreated cells predominantly

exhibited a punctate pattern of HFE expression with a

tubulovesicular concentration in the pericentrosomal

region (Fig. 1A,D), consistent with previous observa-

tions [11,28]. Immunostaining with anti-TfR1, anti-

Rab11a and Rab11-FIP3 Ig has identified the HFE-

containing pericentrosomal compartment of HuTu80

cells as the endosomal recycling compartment (ERC)

[28]. Treatment of HFE-WT–HA-expressing cells with

tunicamycin altered this pattern of localization and

resulted in a reticular pattern of cell localization

(Fig. 1B,D). Immunostaining showed significant

co-localization with the ER chaperone protein BiP,

demonstrating that the HFE-WT–HA was now locali-

zing primarily to the ER (Fig. 1B,D).

A similar pattern of reticular expression and BiP

co-localization was observed when HuTu80 cells were

transfected to express the HH-causing HFE-C282Y

variant (Fig. 1C,D), which has been shown through

multiple biochemical and microscopy approaches to be

retained in the ER [10,13,18,28,29].

HFE is glycosylated at residues Asn110, Asn130

and Asn234

Although the results in Fig. 1 point towards an impor-

tant role for glycosylation in HFE localization, it

remains possible that the effects of tunicamycin treat-

ment were indirect. To directly examine the impor-

tance of glycosylation on HFE, it was necessary to

generate an N-glycosylation-deficient mutant. To this

end, we used a bioinformatic prediction program

(netnglyc 1.0 Server; Technical University of Den-

mark) to identify putative glycosylation sites in the

protein. Consistent with previous predictions [18], we

identified three high-probability sites: asparagines at

positions 110, 130 and 234. Starting with wild-type

HFE, we generated all possible combinations of single

and double putative N-glycosylation site mutants

using site-directed mutagenesis. The wild-type and

mutant expression constructs were transfected into

HEK293T cells and the lysates analysed by western

blotting.

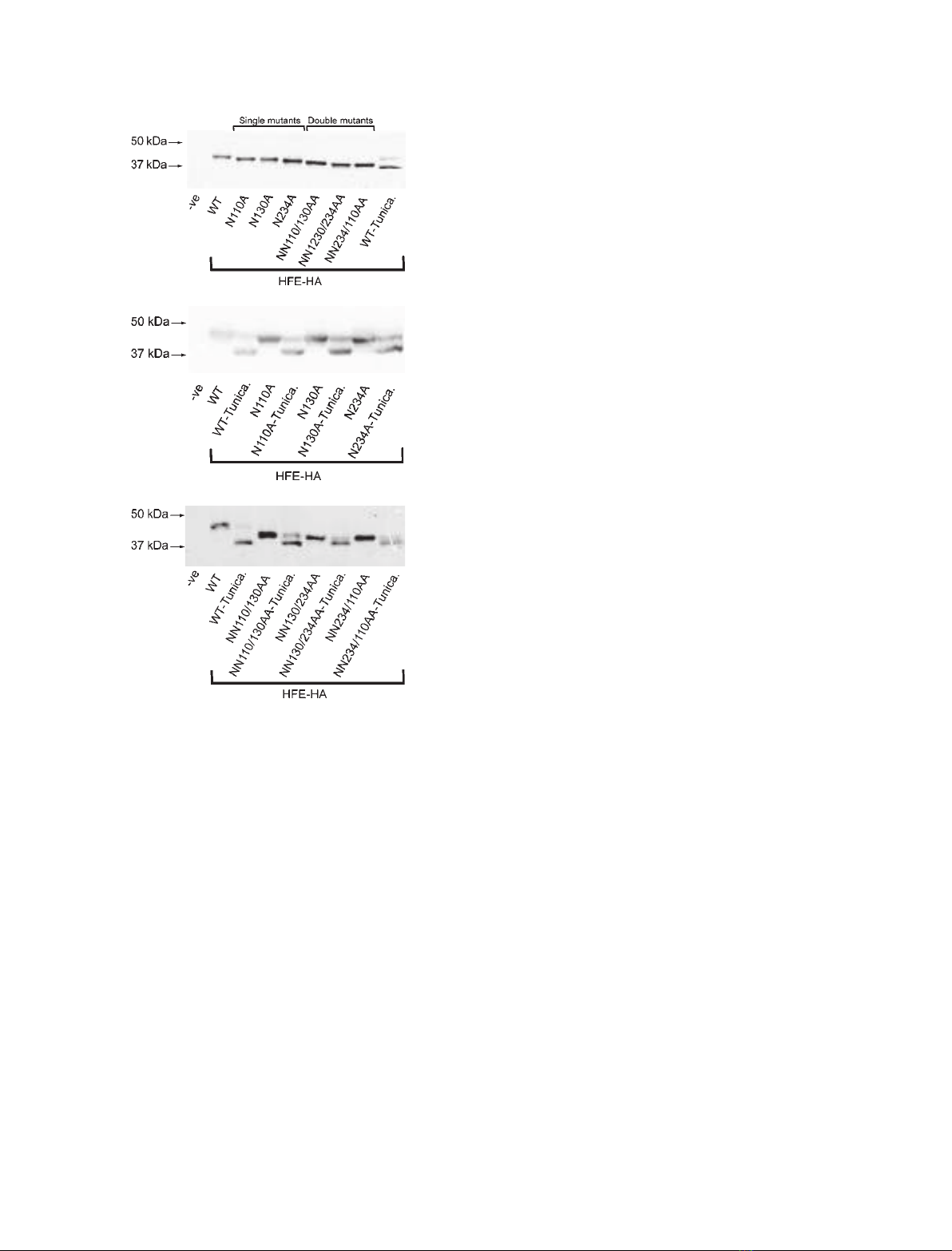

The results from these experiments, which are shown

in Fig. 2A, indicate that the introduction of single ala-

nine mutations at N110, N130 and N234, respectively,

resulted in the production of HFE proteins that

migrated with increased mobility on SDS/PAGE com-

pared with the wild-type. This suggested that all three

sites in the wild-type proteins are capable of becoming

glycosylated. The decrease in apparent molecular mass

became even more pronounced for proteins containing

L. Bhatt et al. N-Glycosylation of HFE

FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 3219–3234 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS 3221

combinations of double mutants, which displayed a

lower apparent molecular mass than either wild-type

or single mutant forms of the protein.

Although immunoblot analysis demonstrated that

the single and double mutants had decreased mass

compared with the wild-type protein, they still

appeared to be of higher molecular mass than the

unglycosylated form of the wild-type HFE protein –

which was produced when wild-type-expressing cells

were treated with tunicamycin (Fig. 2A; WT-Tunica).

This suggested that both the single and double

mutants were still partially glycosylated. To test this,

we transfected HEK293T cells to express either the

wild-type or mutant proteins, and incubated the cells

in the presence or absence of tunicamycin. Drug

treatments resulted in the accumulation of forms of

the mutant proteins that were of lower apparent

molecular mass and of similar size to the unglycosy-

lated form of the wild-type protein (see Fig. 2B for

single mutants and Fig. 2C for double mutants). This

suggested that the mutant proteins do indeed still

undergo limited glycosylation. For the single

mutants, additional supporting evidence for the per-

sistence of N-linked glycans was obtained by PNG-

ase F digestions of immunoprecipitated proteins,

which then migrated with lower apparent molecular

mass compared with the undigested forms (results

not shown).

A

B

C

D

Fig. 1. Inhibition of N-glycosylation influ-

ences patterns of HFE intracellular localiza-

tion. HuTu80 cells were transfected with

constructs expressing the HFE-WT–HA

(A, B) and HFE-C282Y–HA (C) proteins,

HFE-WT-expressing cells were incubated for

1 h in the absence (A) or presence (1B) of

2lgÆmL

–1

tunicamycin (Tunica) as indicated.

Cells were immunostained with anti-HA and

anti-BiP Ig, and processed for fluorescence

microscopy. Co-localization masks were

created as described in Materials and meth-

ods, and represent areas with overlapping

green and red pixels converted to white.

Scale bar, 10 lm. Identical results were

obtained when cells were transfected with

constructs directed to express amino-tagged

GFP–HFE-WT and GFP–HFE-C282Y, and in

general we found that HA and GFP tags

could be interchanged without altering the

pattern of cell localization (data not shown).

Figures shown are representative of at least

three independent experiments. (D) Graph

showing the relative amounts of transfected

cells exhibiting punctate or reticular localiza-

tion of expressed HFE proteins (n= 3).

N-Glycosylation of HFE L. Bhatt et al.

3222 FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 3219–3234 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS

HFE NNN110/130/234/AAA triple mutant is

glycosylation deficient

To investigate whether the three N-glycosylation sites

studied to date are the only sites of HFE N-glycosyla-

tion – and with the aim of producing an HFE mutant

that is completely deficient in N-glycosylation – we

used site-directed mutagenesis to create a NNN110/

130/234AAA triple mutant. To determine the effect of

these combined mutations on HFE, we transfected

HEK293T cells to express wild-type, single, double or

triple mutants.

Western blot analysis of cell lysates shown in Fig.3A

indicated that the triple mutant fractionated with a

lower molecular mass than the wild-type protein, and

either the single or double mutants. This lower molecu-

lar mass form appeared to be the same size as the

unglycosylated form of the wild-type protein produced

in tunicamycin-treated cultures (Fig. 3A; WT-Tunica).

These data suggested that all potential glycosylation

sites had been mutated. To confirm this, we transfected

HEK293T cells to express wild-type or triple mutant

forms of HFE and incubated the cells in the presence

and absence of tunicamycin. Drug treatment resulted

in the accumulation of an unglycosylated lower molec-

ular mass form of the wild-type HFE protein, whereas

it had no effect on the apparent molecular mass of the

triple mutant (Fig. 3B).

In a second approach, HFE was immunoprecipitated

from wild-type or triple-mutant-expressing cells and

incubated with PNGase-F. As is shown in Fig. 3C,

enzyme treatment of wild-type HFE resulted in the

production of a lower molecular mass product. Treat-

ment had no detectable effect on migration of the tri-

ple mutant, which had the same apparent molecular

mass as the PNGase F-treated wild-type protein. We

conclude that HFE is normally glycosylated in vivo at

three sites (N110, N130 and N234), and that mutation

of these sites gives rise to an HFE protein that is

N-glycosylation deficient.

N-Glycosylation of HFE is required for its

appropriate localization to the ERC

Our results from Fig. 1 indicated that tunicamycin

treatment of HFE-WT-expressing cells results in a

reticular localization pattern. To definitively establish

the importance of N-glycosylation on HFE localization

in HuTu80 cells, we transfected cells to express GFP-

tagged forms of wild-type or triple-mutant HFE. As

shown in Fig. 4A, HFE-WT–GFP localized predomi-

nantly to a tubulovesicular structure near the nucleus

with some punctate staining, similar to that observed

in Fig. 1A. The GFP-tagged triple mutant, by contrast,

predominantly displayed a reticular localization pat-

tern (Fig. 4A,B). This was similar to the expression

pattern previously observed for HFE-WT in tunica-

mycin-treated cells (Fig. 1B).

A

B

C

Fig. 2. Characterization of N-glycosylation site single and double

mutants. (A) HEK293T cells were transfected to transiently express

HFE-WT–HA, HFE-N110–HA, HFE-N130A–HA, HFE-N234A–HA, HFE-

NN110/130AA–HA, HFE-NN130/234AA–HA or HFE-NN234/110AA–

HA proteins. HFE-WT–HA expressing cells were incubated for 16 h

before lysis in the presence or absence of 1 mMtunicamycin (Tunica).

Cleared cell lysates were fractioned by 11% SDS/PAGE for immuno-

blotting with a mouse anti-HA Ig. (B) Transiently transfected HEK293T

cells expressing HFE-WT–HA, HFE-N110–HA, HFE-N130A–HA or

HFE-N234A–HA were incubated for 16 h in the presence or absence

of 1 mMtunicamycin as indicated (Tunica). HA-tagged proteins in

cleared cells lysates were detected by immunoblotting with a mouse

anti-HA Ig. (C) Transiently transfected HEK293T cells expressing HFE-

WT–HA, HFE-NN110/130AA–HA, HFE-NN130/234AA–HA or HFE-

NN234/110AA–HA protein were incubated for 16 h in the presence or

absence of 1 mMtunicamycin as indicated (Tunica). HA-tagged pro-

teins in cleared cells lysates were detected by immunoblotting with a

mouse anti-HA Ig.

L. Bhatt et al. N-Glycosylation of HFE

FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 3219–3234 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS 3223