MINIREVIEW

Substrate recognition by the protein disulfide isomerases

Feras Hatahet and Lloyd W. Ruddock

Biocenter Oulu and Department of Biochemistry, University of Oulu, Finland

Introduction

The compartmentalization of cells is essential for life.

Each subcellular compartment has highly defined func-

tions and is highly regulated in terms of biophysical

conditions (pH, ion concentration, etc.), small mole-

cule composition, and protein composition. The endo-

plasmic reticulum (ER) is a compartment with

multiple functions, including steroid production [1,2],

carbohydrate metabolism, including glycogenolysis [3],

transformation of bile pigments [4,5] detoxification of

many drugs [6], calcium storage [7,8] and phospholipid

synthesis [9,10]. However, the primary function of the

ER is usually deemed to be the folding and post-trans-

lational modification of proteins destined for secretion,

the outer membrane and compartments in the secre-

tory pathway such as the Golgi.

Over one-third of all human proteins fold in the ER

[11], and it contains many catalysts that generate

unique post-translational modifications. These range

from the well known, such as disulfide bond formation

[12] and N-glycosylation [13], to the less well known,

such as the formation of formyl-glycine in the active

site of the sulfatases [14,15] or c-carboxyglutamate for-

mation in blood clotting factors [16].

Disulfide bonds are covalent linkages formed

between two cysteine residues in proteins whose pri-

mary function is to stabilize the folded structure of the

protein. As any cysteine residue in a protein has the

potential to form a disulfide bond with another cyste-

ine, either intramolecular or intermolecular, the correct

formation of native disulfide bonds is often the rate-

limiting step in the folding of proteins in vitro and

in vivo [17,18]. Disulfide bond formation is not unique

to the ER; it also occurs in the periplasm of Gram-

negative bacteria [19], in mitochondria [20,21], and

outside the cell, e.g. in blood clotting [22], and there

are a small, but growing, number of examples of

Keywords

diagonal electrophoresis; disulfide bond;

endoplasmic reticulum; glutathione;

molecular chaperone; oxidative protein

folding; protein folding catalyst; substrate

binding

Correspondence

L. W. Ruddock, Biocenter Oulu and

Department of Biochemistry, PO Box 3000,

90014 University of Oulu, Finland

Fax: +358 8 553 1141

Tel: +358 8 553 1683

E-mail: Lloyd.ruddock@oulu.fi

(Received 8 June 2007, revised 27 July

2007, accepted 17 August 2007)

doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2007.06058.x

Protein folding in the endoplasmic reticulum is often associated with the

formation of native disulfide bonds. Their primary function is to stabilize

the folded structure of the protein, although disulfide bond formation can

also play a regulatory role. Native disulfide bond formation is not trivial,

so it is often the rate-limiting step of protein folding both in vivo and

in vitro. Complex coordinated systems of molecular chaperones and protein

folding catalysts have evolved to help proteins attain their correct folded

conformation. This includes a family of enzymes involved in catalyzing

thiol–disulfide exchange in the endoplasmic reticulum, the protein disulfide

isomerase (PDI) family. There are now 17 reported PDI family members in

the endoplasmic reticulum of human cells, but the functional differentiation

of these is far from complete. Despite PDI being the first catalyst of

protein folding reported, there is much that is still not known about its

mechanisms of action. This review will focus on the interactions of the

human PDI family members with substrates, including recent research on

identifying and characterizing their substrate-binding sites and on determin-

ing their natural substrates in vivo.

Abbreviations

ER, endoplasmic reticulum; ERAD, endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation; GSSG, oxidized glutathione; PDI, protein disulfide

isomerase.

FEBS Journal 274 (2007) 5223–5234 ª2007 The Authors Journal compilation ª2007 FEBS 5223

regulatory disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm

[23] or of, perhaps, extensive disulfide bond formation

in the cytoplasm of thermophiles [24]. Although disul-

fide bond formation is not unique to the ER, the com-

plexity of the system, in terms of the number of

substrate proteins that need the addition of disulfide

bonds and the number of enzymes involved in catalyz-

ing the process, is unique.

Disulfide bond formation in the ER

The process of native disulfide bond formation in the

ER is known to be catalyzed by several families of

enzymes. However, although some of the participants

in the cellular process are known, their precise roles

and mechanisms of action are still largely unknown.

Native disulfide bond formation can occur via multiple

parallel pathways, and this significantly complicates

the interpretation of in vivo data. For example, there

appear to be at least five potential parallel pathways

for oxidation (disulfide bond formation) in substrate

proteins. The first is direct oxidation of dithiols in

folding proteins by molecular oxygen )however, this

reaction, unless catalyzed, is probably too slow to be

physiologically relevant. The second is oxidation by low

molecular weight biochemical compounds such as oxi-

dized glutathione (GSSG) [25–27]. The third is oxida-

tion catalyzed by proteins belonging to the thioredoxin

superfamily, such as protein disulfide isomerase (PDI)

[28,29]. However, as highlighted in an excellent recent

review [30], strictly speaking, neither the PDIs nor

GSSG by themselves have oxidase activity, as neither

utilizes molecular oxygen and both are converted into

the reduced form by their donation of a disulfide bond

to a substrate protein; hence, both need to be

reoxidized to complete the catalytic cycle. The fourth

is oxidation by flavin-dependent sulfhydryl oxidases

[31,32]. However, there is little supporting evidence for

a normal physiological role of the QSOX sulfhydryl

oxidases in disulfide bond formation in the ER [33],

whereas the active site of yFMO [31] probably faces

the cytosol and not the ER lumen. The fifth is oxida-

tion by Ero1, although the evidence to date [34–37]

suggests that this occurs indirectly via PDI family

members, with no evidence of direct oxidation of

substrate proteins. Although the gene products of

ERO1 and PDI1 are essential for viability in yeast

[38,39] and those of the other components, including

the glutathione biosynthetic pathway, are not, it is still

unclear to what extent the five possible oxidative path-

ways contribute to native disulfide bond formation

under physiologically normal conditions. What is clear

is that the rate-limiting step for native disulfide bond

formation in proteins that contain multiple disulfides

comprises late-stage isomerization reactions, where

disulfide bond formation is linked to conformational

changes in protein substrates with substantial regular

secondary structure. These steps are only catalyzed

by members of the PDI family, and hence knowl-

edge of the mechanisms of action of these proteins is

critical for our understanding of native disulfide bond

formation.

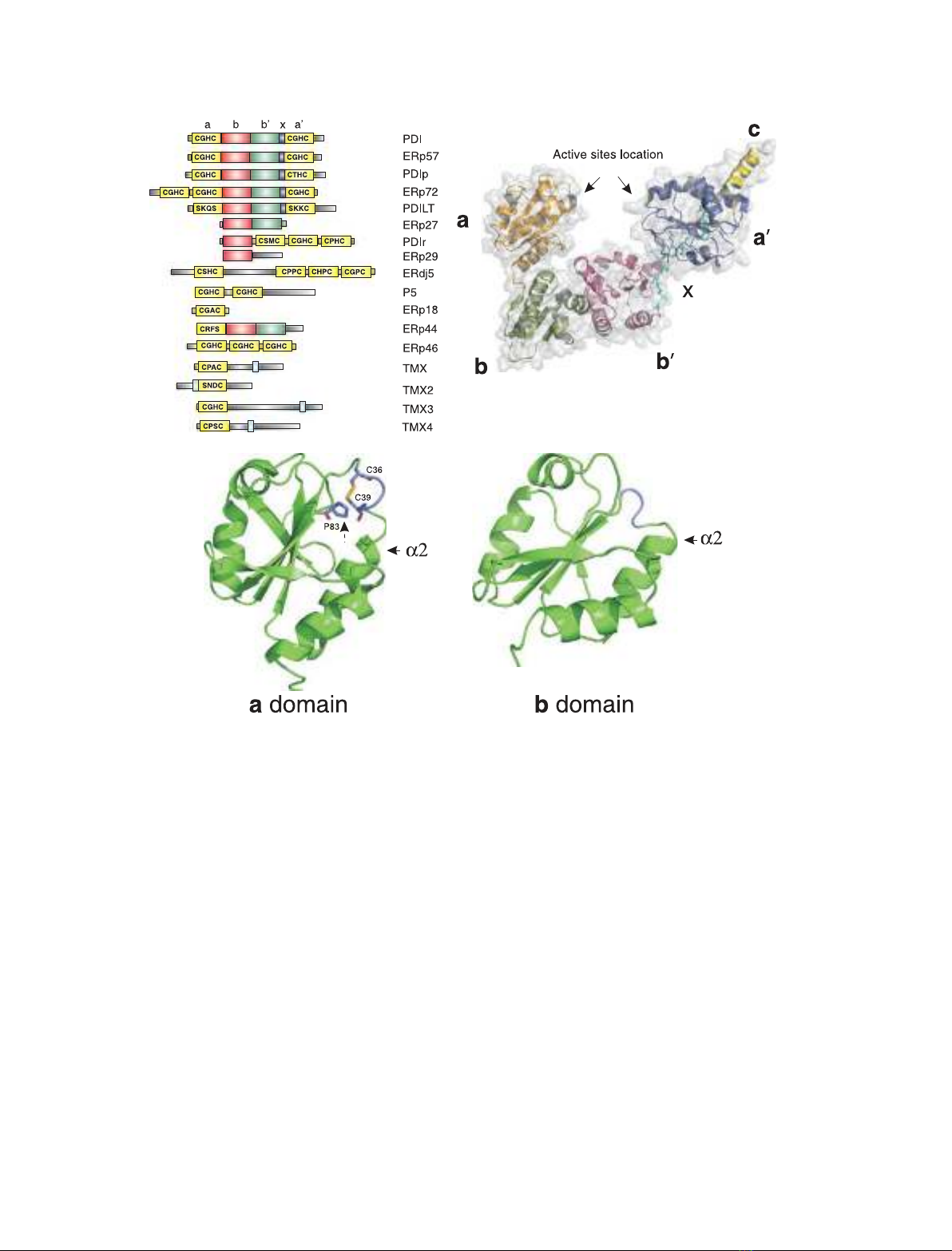

PDI was the first protein-folding catalyst reported

(over 40 years ago [40]), but as yet significant details

of its mechanism of action are unknown. PDI is a

multidomain protein with two catalytic domains, aand

a¢, which are separated by two noncatalytic domains b

and b¢. In addition, there is a 19 amino acid linker

region between b¢and a¢, designated x, and a highly

acidic C-terminal extension, designated c, which con-

tains the C-terminal ER-localization motif KDEL and

that has a low affinity for Ca

2+

, but that seems to

have no function in the catalysis of native disulfide

bond formation by PDI (Fig. 1). The structures of the

a-domain, b-domain and a¢-domain of human PDI

have been solved by NMR [41,42] and (PDB file

1X5C, N Tochoi, S Koshiba, M Inoue, T Kigwa & S

Yokoyama, unpublished results), but both the isolated

b¢-domain of human PDI and all multidomain cata-

lytic PDI family members have proved intransigent to

structure resolution for over 30 years, with the recent

exception of yeast Pdi1p [43] (Fig. 1B). Over the past

decade, the number of PDI family members in mam-

malian cells has grown, and there are now 17 reported

family members in humans [28], two of which, ERp57

and PDIp, share the same domain architecture as PDI

(Fig. 1). With the exception of the first domain of

ERp29 [44], all of the PDI family member domains

solved to date share the thioredoxin fold, an ab-fold

with a mixed b-sheet core [41–43,45,46] and (PDB files

1X5C, 1X5D, 1X5E, 2DIZ, 2DJ1, 2DJ2, 2DJ3, 2DML

and 2DMM, N Tochoi, S Koshiba, M Inoue, T Kigwa

& S Yokoyama; ISEN, ZJ Liu, L Chen, W Tempel, A

Shah, D Lee, JP Rose, DC Richardson, JS Richardson

& BC Wang, unpublished results). In the catalytically

active domains, the CXXC active site, which exists in

dithiol, disulfide and mixed disulfide states during the

catalytic cycle, lies at the N-terminus of a2. Spatially

juxtaposed is a cis-proline (Fig. 1C) that lies before b4

and that is implicated in substrate interactions in other

thioredoxin superfamily members [47,48]. Despite the

name, five of the 17 human PDI family members,

PDILT, ERp27, ERp29, ERp44, and TMX2, lack a

CXXC active site and therefore may not be involved in

catalyzing native disulfide bond formation. This poten-

tial confusion over the family name arises because the

PDI–substrate interactions F. Hatahet and L. W. Ruddock

5224 FEBS Journal 274 (2007) 5223–5234 ª2007 The Authors Journal compilation ª2007 FEBS

PDI family is a subfamily of the thioredoxin superfam-

ily, which is defined by subcellular localization, i.e. by

being in the ER, rather than by function.

In addition to having a role in protein folding in the

ER, PDI is the b-subunit of prolyl-4-hydroxylase [49]

and microsomal triglyceride transfer protein [50], and

A

C

B

Fig. 1. The architecture of the PDI family. (A) Domain structures of the human PDI family. PDI has a four-domain structure, the catalytic

a-domain and a¢-domain being separated by the noncatalytic b-domain and b¢-domain. Whereas the b¢-domain provides the primary sub-

strate-binding site of human PDI, no physiological function has been assigned to the b-domain, and it is probably structural in nature.

Whereas the linkers between the a-domain and b-domain and between the b-domain and b¢-domain are very short, the b¢-domain and

a¢-domain are linked by a 17 amino acid linker designated x[81]. Other PDI family members either have a similar overall domain architecture

to that of PDI, e.g. ERp57 and PDIp, or have different combinations of catalytic and noncatalytic domains. (B) X-ray structure of Saccharomy-

ces cerevisiae Pdi1p. The only full-length structure of a catalytically active PDI family member reported is that of S. cerevisiae Pdi1p [44].

Each of the four domains of Pdi1p, a,b,b¢and a¢, shows a thioredoxin fold. The active site motifs (marked with arrows) in the a-domain

and a¢-domain lie close to each other. In the reported structure, the b-domain of one molecule of Pdi1p is located in the putative substrate-

binding pocket formed between the other four domains of another molecule of Pdi1p; this may have resulted in increased rigidity and have

allowed the crystal to form. (C) NMR structures of the a-domain and b-domain of human PDI. The a-domain of human PDI [41] shares the

same fold as the archetypal member of the superfamily, thioredoxin. It has a five-stranded mixed b-sheet surrounded by four a-helices. The

active site motif (C36 and C39) lies at the N-terminus of a2, and the helix dipole is thought to contribute to the nucleophilicity of the N-termi-

nal active site cysteine. There is also a conserved cis-proline in the structure (marked with a dashed arrow) located before b4. This residue

has been implicated in substrate binding within the superfamily [50,51]. Despite having virtually no sequence similarity with the a-domain,

the b-domain [42] also has a thioredoxin fold, although it lacks the active site and the cis-proline. The substrate-binding site in the b¢-domain

(which is homologous to the b-domain) is located at the same position as the active site in the a-domain and a¢-domain. The structure of the

a¢-domain (PDB file 1X5C, N Tochoi, S Koshiba, M Inoue, T Kigwa & S Yokoyama, unpublished results) is not shown, but it is similar to that

of the a-domain.

F. Hatahet and L. W. Ruddock PDI–substrate interactions

FEBS Journal 274 (2007) 5223–5234 ª2007 The Authors Journal compilation ª2007 FEBS 5225

PDI family members are involved in ER-associated

degradation (ERAD [51–53]), although it is still

unclear which family member(s) plays the primary role

in disulfide reduction in proteins targeted for degrada-

tion, and in retrotranslocation of bacterial toxins

[54,55] and viruses [56], which hijack normal cellular

processes to exert their biological effect. In addition,

PDI family members have been reported to be

involved in a wide range of biological processes

located in nearly every cellular compartment [57]. The

role of PDI family members in these processes, which

include sperm–egg fusion, blood clotting, and integrin

ligation [58–60], is often determined by the use of

inhibitors, which may not be specific for only one fam-

ily member, and by the use of inhibitory antibodies,

which have often not been tested for crossreactivity.

Hence, in many cases it is not completely clear which

PDI family member is involved. In all cases, further

clarification is required as to how the PDI family

member escapes the ER, as most have consensus C-ter-

minal ER-localization motifs; for example, PDI,

ERdj5, P5 and ERp46 have KDEL. Furthermore, the

interaction of substrates with PDI family members is

one of the mechanisms involved in keeping non-native

proteins in the ER [61,62]. This question of nonexpect-

ed localization is especially relevant for nonsecretory

pathway compartments, as there are no known experi-

mentally confirmed splice variants of PDI family mem-

bers that lack the N-terminal ER signal sequence.

To understand the mechanisms of action of the PDI

family, we must understand the nature of the interac-

tion(s) between PDI family members and their sub-

strates, including the specificities of substrate binding.

However, substrate binding is complex, in part because

PDI family members appear to have very broad speci-

ficities and in part because they have multiple sub-

strate-binding sites. It should be noted that although

the specificity of substrate binding and the specificity

of the catalysis of thiol–disulfide exchange are inter-

linked, they are not the same thing. Specifically, the

rate of catalysis of thiol–disulfide exchange by PDI

family members is not directly linked to substrate-

binding affinity, and each PDI family member may be

able to bind substrates in which it is unable to catalyze

thiol–disulfide exchange. In addition to binding protein

substrates, at least one PDI family member must be

able to trigger conformational changes in bound non-

native protein subtrates to allow access to buried

disulfides or free thiols in folding intermediates with

substantial regular secondary structure. This is an area

that has been poorly studied, due to the extreme

difficulty in isolating ⁄identifying intermediates and

following the process.

Folding catalyst or molecular

chaperone?

Since the experiments by Anfinsen [63], it is generally

accepted that the final structure of a protein is deter-

mined solely by the primary sequence of the protein,

plus post-translational modifications, and the physical

properties of the solution, such as pH and ionic

strength. However, for the majority of proteins, there

are auxiliary molecules inside the cell that help the

protein to attain this final conformation. These fall

into two broad types: protein-folding catalysts and

molecular chaperones. Protein-folding catalysts acceler-

ate slow steps in the productive folding pathway. In

contrast, the net effect of molecular chaperones is to

inhibit steps in nonproductive folding pathways. For

example, they prevent partially folded intermediates

from aggregating, or delay the initiation of folding

until appropriate sequences have been translated. PDI

is a protein-folding catalyst that accelerates the forma-

tion of native disulfide bonds, whose noncatalyzed for-

mation, even in a physiological redox buffer, can take

days. PDI is also reported to have molecular chaper-

one activity [64,65], as it is able to prevent the aggrega-

tion of proteins that do not contain cysteine residues.

Often, these activities are seen as being distinct, but

they should not be. For PDI family members to work

as protein-folding catalysts, they require molecular

chaperone-like properties, i.e. the ability to recognize

and interact with non-native proteins and so allow

catalysis of disulfide bond formation, including gaining

access to buried thiols and disulfide bonds, and simul-

taneously preventing non-specific interactions between

partially folded intermediates.

Molecular chaperones and protein-folding catalysts

have the ability to bind a very large number of differ-

ent substrates. For example, approximately 7500 pro-

teins fold in the human ER [11], the majority of which

require native disulfide bond formation and hence

probably interact with a catalytically active PDI family

member. There is an added complexity in that for each

folding protein there will be multiple folding intermedi-

ates, from ‘unfolded’ through to quasi-native states.

For the well-studied folding pathway of bovine pancre-

atic trypsin inhibitor [17,66,67], PDI is able to catalyze

all of the steps in the folding reaction, implying that it

recognizes all folding intermediates in the pathway.

Whereas the ER lectin-based molecular chaperones,

such as calnexin and calreticulin, have a highly specific

recognition motif, binding only monoglucosylated

N-glycans [68,69], those chaperones that bind protein

substrates directly appear to have much broader speci-

ficities. For example, using a peptide phage display

PDI–substrate interactions F. Hatahet and L. W. Ruddock

5226 FEBS Journal 274 (2007) 5223–5234 ª2007 The Authors Journal compilation ª2007 FEBS

library, Gething and coworkers were able to demon-

strate that BiP, the ER-resident HSP70, recognized

sequences with the motif HyXHyXHyXHy (where Hy

is a large hydrophobic amino acid) and in particular

the sequence (WF)X(WF)X(WFLI)X(WFYL) [70]; this

sequence can be found in 1032 human proteins. One

common feature of molecular chaperones is that they

bind substrates with relatively low affinity. For exam-

ple, BiP binds synthetic peptides with consensus motifs

with 10–60 lmaffinity [70]. A recent landmark paper

monitoring chaperone engagement of substrates in the

ER of live cells [71] elegantly showed that chaperone

substrate interactions in vivo are very dynamic, with

rapid sampling and release. In this context, it is also

important to remember that equivalent affinities do

not mean equivalent dynamics. For example, the affin-

ity of calreticulin for substrate is about 2 lm, and that

of calreticulin for ERp57 is comparable at around

18 lm, but the exchange rate of K

off

for N-glycopro-

teins is 10

5

-fold slower than that for ERp57 [72,73].

The affinity of PDI for substrates is comparable to

that of molecular chaperones [74,75], with the highest

affinity for a noncysteine-containing peptide substrate

known to the authors being about 0.25 lm(A Pirnes-

koski and LW Ruddock, unpublished results). This

low affinity and the high dynamics make it difficult to

study PDI–substrate interactions in complex mixtures

or in vivo unless the proteins are physically joined

together by the addition of chemical crosslinkers. The

use of chemical crosslinkers, although potentially

prone to artefacts, has allowed the identification of

multiple binding sites on human PDI family members

and determination of the specificity of one family

member (see below).

The substrate-binding sites of PDI

Initial attempts to identify the substrate-binding site

in PDI family members were based on the interaction

of domain constructs of human PDI expressed rec-

ombinantly in Escherichia coli with small peptide

ligands such as D-somatostatin and with non-native

proteins such as scrambled RNase. The results indi-

cated that the noncatalytic b¢-domain was essential

and sufficient for the binding of small peptides,

whereas the catalytic a-domain and a¢-domain also

contributed to the binding of larger peptides and

non-native proteins [76]. These interactions were pri-

marily hydrophobic in nature, consistent with a role

in binding non-native proteins. These results correlate

well with studies published around the same time on

the activities of equivalent domain constructs, which

showed that thiol–disulfide exchange could be cata-

lyzed by any construct containing either the

a-domain or a¢-domain, that disulfide isomerization

required a linear combination of one of these cata-

lytic domains plus the b¢-domain, and that complex

isomerization, i.e. isomerization in protein substrates

with substantial regular secondary structure, required

the whole protein excluding the c-region [77]. Hence,

the b¢-domain is required to bind non-native protein

substrates with reasonable affinity to allow the cata-

lytic domains to act on them. Follow-up studies on

the b¢-domain binding site by modeling and mutagen-

esis identified the binding site as being in a homolo-

gous location to the catalytic site in the a-domain

and a¢-domain (Fig. 1B) [78]). Furthermore, parallel

studies determined: (a) that the binding specificity of

the b¢-domain in PDIp was a single tyrosine or tryp-

tophan with no adjacent negative charge [79];

(b) that the specificity of PDIp for substrates could

be modulated by mutating analogous residues to

those that formed the substrate-binding site of PDI

(KEH Salo and LW Ruddock, unpublished results);

(c) that this binding site in the b¢-domain of ERp57

had become specialized for the interaction of ERp57

with the P-domains of calreticulin and calnexin [80];

and (d) that an overlapping site in the second

domain of ERp29 and the Drosophila ERp29 homo-

log was used to bind substrates [81,82].

Since the first publication on the substrate-binding

properties of the b¢-domain, this site has been referred

to as the primary substrate-binding site of PDI, imply-

ing that it is not the only site of interaction between

PDI family members and their substrates. There are

three pieces of evidence indicating that there are

secondary substrate-binding sites in the a-domain and

a¢-domain. First, the isolated a-domain and a¢-domain

are able to catalyze thiol–disulfide exchange in small

peptide substrates, for which they must have a reason-

able affinity [83]. Secondly, in vivo crosslinking studies

indicated that the binding of larger peptides required a

linear combination that included both b¢and aor a¢,

and the efficient crosslinking of non-native proteins

required the whole protein except the c-region [76].

Third, studies on the interaction of PDI with the

a-subunit of prolyl-4-hydroxylase to form a stable

active tetramer allowed the identification of interaction

sites in the a-domain, b¢-domain and a¢-domain of

PDI, with the site in the b¢-domain being equivalent to

the primary substrate-binding site [84]. Parallel studies

with the binding of non-native proteins implicated the

same sites in the a-domain, b¢-domain and a¢-domain

in PDI substrate binding (HI Alanen and LW Rud-

dock, unpublished results). The site identified in the

a¢-domain partially overlaps with a tripeptide-binding

F. Hatahet and L. W. Ruddock PDI–substrate interactions

FEBS Journal 274 (2007) 5223–5234 ª2007 The Authors Journal compilation ª2007 FEBS 5227