Extraction and characterization of pectin from Yuza (Citrus junos) pomace:

A comparison of conventional-chemical and combined physicaleenzymatic

extractions

Jongbin Lim, Jiyoung Yoo, Sanghoon Ko, Suyong Lee

*

Department of Food Science & Technology and Carbohydrate Bioproduct Research Center, Sejong University, 98 Gunja-dong, Gwangjin-gu, Seoul 143-747, Republic of Korea

article info

Article history:

Received 20 May 2011

Accepted 23 February 2012

Keywords:

Yuza

Pectin

Physicaleenzymatic extraction

Rheology

Mixolab

abstract

Pectin from Yuza (Citrus junos) pomace was extracted by using combined physical and enzymatic (CPE)

treatment, and their characteristics were compared with those of chemically-extracted pectin. Their

physico-chemical and thermo-mechanical properties were also investigated in a wheat flourewater

system. The CPE extraction produced pectin with 55% of galaturonic acid and the extraction yield was

7.3%. Also, the pectin obtained by CPE extraction exhibited a higher degree of esterification (46%) than

chemically-extracted pectin (41%), which was confirmed by FT-IR analysis. When the pectin solutions

were subjected to steady-shear conditions, both samples had shear-thinning properties while high

apparent viscosity was observed in the chemically-extracted pectin. Even though the use of both pectins

raised the pasting parameters of wheat flour as well as its gelatinization temperature, less change in the

pasting properties was found in the wheat flourewater system containing the pectin prepared by CPE

treatment. The Mixolab results demonstrated that during mechanical shearing and thermal treatments,

the dough samples containing chemically-extracted pectin exhibited enhanced mixing stability, strong

protein network structure, and increased peak viscosity.

Ó2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

Yuza belongs to citrus fruits (scientifically called Citrus junos)

and is commercially cultivated in northeast Asian countries such as

Korea, China, and Japan. Due to the uniquely tart flavor of Yuza, it is

rarely consumed as a raw fruit; its juice is mainly used as an

aromatic ingredient to produce a variety of processed foods such as

teas, drinks, and dressings. The Food and Agriculture Organization

recently reported that the total production of Yuza-processed

products in Korea has almost doubled since 2000 and also that

the preserved-Yuza market in Japan increased to 4.5 billion Yen in

2010 (FAO, 2010). Correspondingly, high amounts of Yuza pomace

(approximately 1800 ton/year) have been produced. Yuza pomace

is however disregarded as processing by-products, probably

causing environmental and economic problems for waste disposal.

Hence, there has been scientific and industrial interest in searching

for a way to utilize Yuza pomace. From a food-industrial point of

view, it would be worthwhile to utilize Yuza pomace as a source of

dietary fiber (specially, pectin) (Kim, 1999;Park, Lee, Chang, & Kim,

2001).

Extensively used as a gelling and thickening agent, pectin has

been industrially obtained under acidic conditions with oxalic

(Koubala et al., 2008), hydrochloric (Hwang, Kim, & Kim, 1998), and

sulphuric acid (Garna et al., 2007). Although the use of strong acids

provides high extraction yield and time-saving advantages, it can

cause serious environmental problems such as the disposal of

acidic wastewater and also play a negative role in consumer pref-

erence. Alternative treatments have been therefore taken into

account for minimizing the use of detrimental chemicals during

pectin extraction. Thus, several thermal and/or mechanical treat-

ments have been applied to extract pectin including ultrasound

(Panchev, Kirchev, & Kratchanov, 1988), autoclaving (Oosterveld,

Beldman, Schols, & Voragen, 2000), extrusion (Shin, Kim, Cho, &

Hwang, 2005), and subcritical water extraction (Tanaka,

Takamizu, Hoshino, Sasaki, & Goto, in press;Ueno, Tanaka,

Hosino, Sasaki, & Goto, 2008). In addition, natural catalysis with

endo-polygalacturonase (Contreras-Esquivel, Voget, Vita, Espinoza-

Perez, & Renard, 2006), (hemi)cellulase (Shkodina, Zeltser,

Selivanov, & Ignatov, 1998;Zykwinska et al., 2008), protease

(Zykwinska et al., 2008), and microbial enzymes (Ptichkina,

Markina, & Rumyantseva, 2008) have been used so far. However,

*Corresponding author. Tel.: þ82 2 3408 3227; fax: þ82 2 3408 4319.

E-mail address: suyonglee@sejong.ac.kr (S. Lee).

Contents lists available at SciVerse ScienceDirect

Food Hydrocolloids

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/foodhyd

0268-005X/$ esee front matter Ó2012 Elsevier Ltd. All rights reserved.

doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.02.018

Food Hydrocolloids 29 (2012) 160e165

there is a limited trial to extract pectin from Yuza pomace by

combined thermo-mechanical and enzymatic methods. Further-

more, pectin is shown to have a different structure and confor-

mation such as the distribution of methoxyl groups and degree of

esterification, depending on the extraction method used. This

suggests that the physico-chemical properties of pectin can be

significantly varied by the extraction method. Nonetheless, most

studies on pectin extractions have also paid primary attention to

the yield and chemical composition of extracted pectin of which

various properties were not characterized and compared with

those of the pectin extracted in a conventional chemical way.

Furthermore, comparisons have not been carried out in a food

model system for practical food applications.

In this study, pectin from Yuza pomace was extracted by

combined physical/enzymatic treatments without any use of acidic

chemicals and its physico-chemical, structural, and thermo-

mechanical properties were investigated and compared with

those of chemically-extracted pectin.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

Yuza pomace left from Yuza juice extraction was provided by

Hansung Food Co. (Jeollanam-do, Korea) and oven-dried at 80

C. It

was then ground to pass through a 100-mesh sieve. All chemicals

used in this study were of analytical grade and Viscozyme

Ò

L,

a multienzyme complex prepared from Aspergillus aculeatus,was

obtained from Novozymes (Bagsvaerd, Denmark).

2.2. Pectin extraction

Chemical and combined physical/enzymatic methods were

applied to extract pectin from Yuza pomace. In the case of the

conventional chemical method (Koubala et al., 2008), the dried

Yuza pomace powder was treated four times with 85% ethanol at

70

C for 20 min, followed by filtration with miracloth (Merck

KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). The residue (10 g) was stirred with

oxalic acid/ammonium oxalate (0.25%, pH 4.6, 400 mL) at 85

C for

1 h and filtered with miracloth. Three volumes of 96% ethanol were

added to the filtrate and centrifuged at 14,500g for 10 min. The

precipitate was washed with 70% and 90% ethanol and then oven-

dried at 50

C for 24 h. According to the method of Min et al. (2011),

the combined physical/enzymatic treatment was also applied to

obtain pectin from Yuza pomace. The suspension of Yuza powder in

distilled water (5%, w/v) was agitated for 5 min at room tempera-

ture and filtered with miracloth. After mixing with distilled water

(5%, w/v) again, the residue was autoclaved at 121

C for 5 min,

followed by enzymatic treatment with Viscozyme

Ò

L with

1.2 10

4

fungal

b

-glucanase unit (40

C, 1 h). After boiling for

5 min to inactivate the enzyme, the suspension was dialyzed

(Spectrum Laboratories Inc., CA, USA) against distilled water for

24 h and freeze-dried.

2.3. Chemical and structural analysis

The contents of galacturonic acid and methanol in pectin were

investigated by spectrophotometric methods at 525 nm and

enzymatic treatments with alcohol oxidase, respectively (Klavons &

Bennett, 1986;Smout, Sila, Vu, Van Loey, & Hendrickx, 2005), and

the degree of esterification was obtained from the molar ratio of

methanol to galacturonic acid. Also, for the neutral sugar compo-

sition of pectin, HPAEC-PAD system (Bio-LC

Ò

, Dionex Corporation,

CA, USA) was used with a CarboPacÔPA1 column (4 250 mm,

Dionex Corporation, CA, USA) according to the method of Rascón-

Chu et al. (2009), and an FT-IR spectrometer (Nicolet Instrument

Co., Madison, WI) was employed to investigate the chemical

structure of pectin. The molecular weight distribution of pectin was

determined by high performance size exclusion chromatography

equipped with two columns in series (BioSep-SEC-S2000 and

S4000, Phenomenex Inc., CA, USA) and a refractive index detector

(Agilent 1100 series, CA, USA). Pullulans with known Mw (Shodex

standard, Showa Denko, Tokyo, Japan) were used as standards.

2.4. Rheological measurement

The flow behaviors of pectin solutions were investigated by

using a controlled-stress rheometer (AR1500ex, TA Instruments,

USA) with a 40 mm parallel plate. The solution for rheological tests

was prepared by mixing pectin with distilled water (3, 5, and 7%, w/

w) and heated at 80

C for 15 min. The pectin solutions were

subjected to steady-shearing at 25

C and the shear rates tested in

this study ranged from 1 to 500 s

1

. The reported rheological curves

were mean values of three measurements.

2.5. Thermal analysis

Thermal analysis was carried out using a differential scanning

calorimeter (DSC 200 F3 Maia, NETZSCH, Bavaria, Germany) which

was calibrated with indium (156.6

C, 28.591 J/g). Wheat flour

(5 mg) was weighed in a pan and either distilled water (25

m

L) or

pectin solution (0.5, 1.0, and 1.5%, w/w) was added. After hermet-

ically sealed, the pans were heated from 30 to 90

C at a rate of 5

C/

min and distilled water was used as reference. From the DSC curves

obtained, the peak enthalpy and temperature of starch gelatiniza-

tion were measured.

2.6. Pasting property measurement

The changes in the pasting property of wheat flour containing

pectin were investigated by using a rheometer equipped with

a starch-pasting cell (AR1500ex, TA Instruments, USA). 10.5% (w/w,

db) wheat flour slurries in 25 g of distilled water or pectin solutions

(0.5,1.0, and 1.5%, w/w) were prepared in an aluminum canister and

subjected to a programmed heating and cooling cycle where the

samples were held at 50

C for 1 min, heated to 95

Cat12

C/min,

maintained at 95

C for 2.5 min, cooled to 50

Cat12

C/min, and

allowed to stand at 50

C for 2 min.

2.7. Statistical analysis

All measurements were made in triplicate and the analysis of

variance (ANOVA) for a randomized block design was applied to

investigate the significance of difference among the samples.

Duncan’s multiple range test was then used for mean comparisons

at a confidence level of 95%.

3. Results and discussion

The yield and chemical composition of Yuza pectin extracted by

the combined physicaleenzymatic (CPE) method were investigated

and compared with those of chemically-extracted pectin. As can be

seen in Table 1, the yield of pectin extracted in a physical/enzymatic

way was determined to be 7.3%, which was slightly lower than that

of chemically-extracted pectin. It was reported that the yield of the

pectin from Yuza was typically 4e19%, depending on extraction

conditions (Park et al., 2001). It is well recognized that pectin is

composed of linear chains of galacturonic acid that are occasionally

interrupted by rhamnose and has side chains of other sugars (Shin

& Hwang, 2002). Thus, Table 1 also shows the content of

J. Lim et al. / Food Hydrocolloids 29 (2012) 160e165 161

galacturonic acid and neutral sugar in the pectins extracted by the

two different methods. The galacturonic acid content of 54.5% was

observed in the pectin obtained by CPE extraction, while

chemically-extracted pectin contained higher amounts of gal-

acturonic acid (72.3%). Thus, pectin was more effectively extracted

from Yuza pomace in a chemical way with acids, compared with

combined physical/enzymatic method. It is recognized that an

increase in acid strength (that is, decreasing pH) plays an important

role in increasing the content of galacturonic acid (Yapo, Robert,

Etienne, Wathelet, & Paquot, 2007). In addition, the physical/

enzymatic treatment could enhance the solubilization of non-

pectic compounds during pectin extraction, negatively contrib-

uting to the purity of galacturonic acid. In the case of neutral sugar,

arabinose and galactose were the main neutral sugars, representing

more than half of total neutral sugar. Moreover, rhamnose, glucose,

and xylose were included in both pectin samples. However,

compared to the pectin obtained by CPE extraction (17.6%),

chemically-extracted pectin contained less neutral sugar residues

(11.1%). Thus, greater loss of neutral sugar appeared to take place

during the acid-based extraction because neutral sugar linkage was

more susceptible to hydrolysis at low pH (Garna et al., 2007). The

combined physical/enzymatic treatment produced pectin with

a 46% degree of esterification which was 41% for chemically-

extracted pectin, thereby demonstrating that both pectins

belonged to low methoxyl pectins. According to a preceding study

(Park et al., 2001), Yuza pectin was extracted with citric, tartaric,

and hydrochloric acids, and the degree of esterification of the

extracted Yuza pectin ranged from 42 to 47%, which was favorably

compared to our results. Furthermore, it was previously reported

that enzymatic de-esterification of pectin by pectinesterase

produced blocks of carboxyl groups in the pectin backbone while

acid de-esterification was a random process (Taylor, 1982). Thus,

the low methoxyl pectins prepared by combined physical/enzy-

matic treatment might have a more blockwise distribution of

methoxyl groups because the enzyme used in this study

(Viscozyme

Ò

L) contains multiple activities including pectines-

terase (Koley, Walia, Nath, Awasthi, & Kaur, 2011).

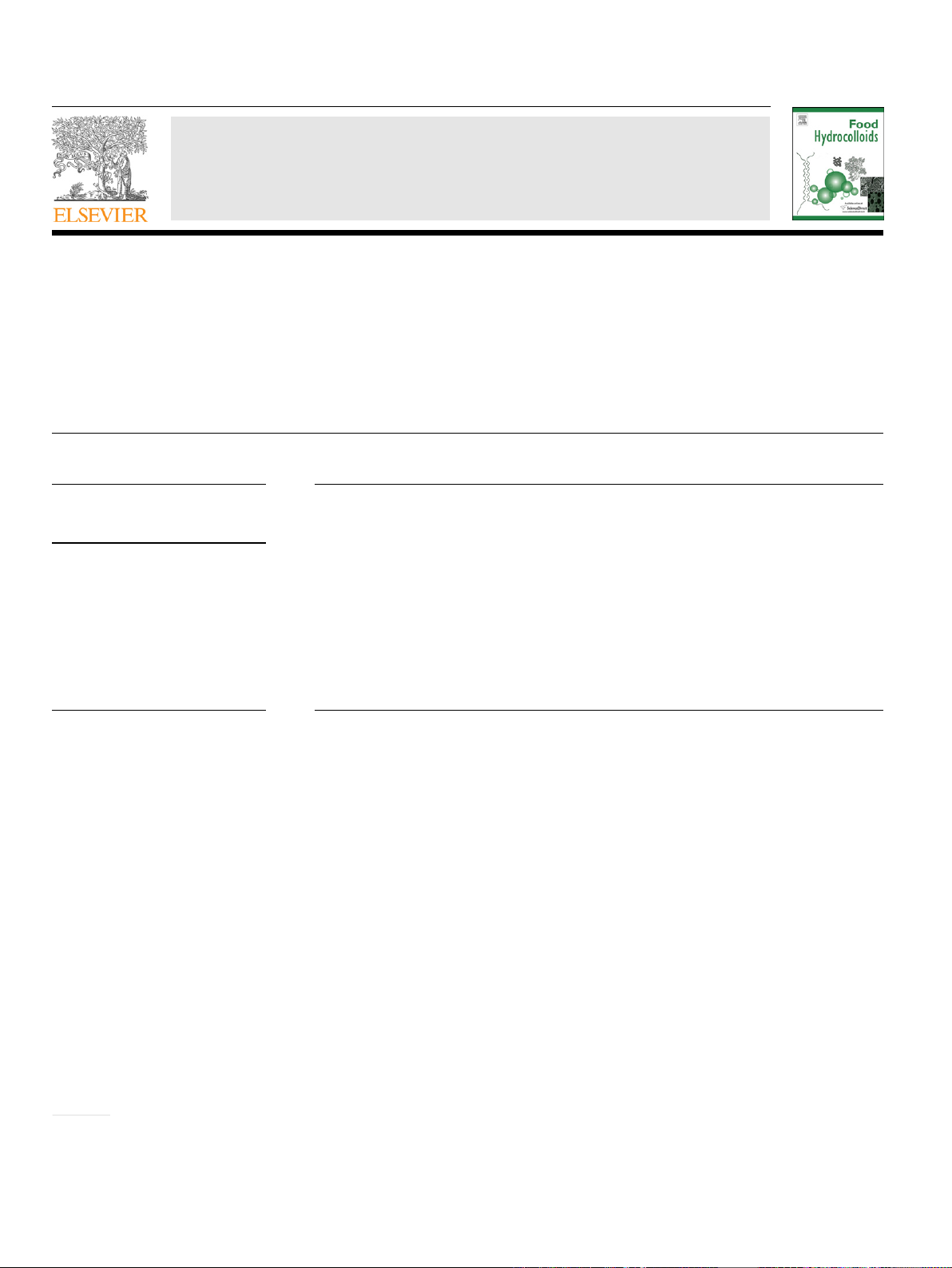

The chemical structure of the pectin obtained by two different

extraction methods was investigated by FT-IR. As shown in Fig. 1,an

absorption peak at 2930 cm

1

was observed for both samples,

corresponding to OeCH

3

stretching from methyl esters of gal-

acturonic acid (Liu, Cao, Huang, Cai, & Yao, 2010). Also, the carbonyl

absorption bands from free and esterified carboxyl groups were at

1620 and 1740 cm

1

, respectively (Gnanasambandam & Proctor,

2000;Liu, Cao, Huang, Cai, & Yao, 2010). However, the intensity

ratio between two peaks was distinctly different depending on the

extraction method. Specifically, the pectin extracted by CPE treat-

ments exhibited a greater intensity ratio of ester carbonyl to free

carboxyl peaks, compared to chemically-extracted pectin. It could

readily be explained by the difference in the degree of esterification

between two pectin samples. Moreover, the strong peak intensity

of total carbonyl groups was observed in chemically-extracted

pectin as expected from the content of galacturonic acid

(Table 1). Additionally, Fellah, Anjukandi, Waterland, and Williams

(2009) proposed a new method to investigate the degree of ester-

ification of pectin, which was determined from the intensity

difference between asymmetric CH

3

stretches and backbone ring

vibration.

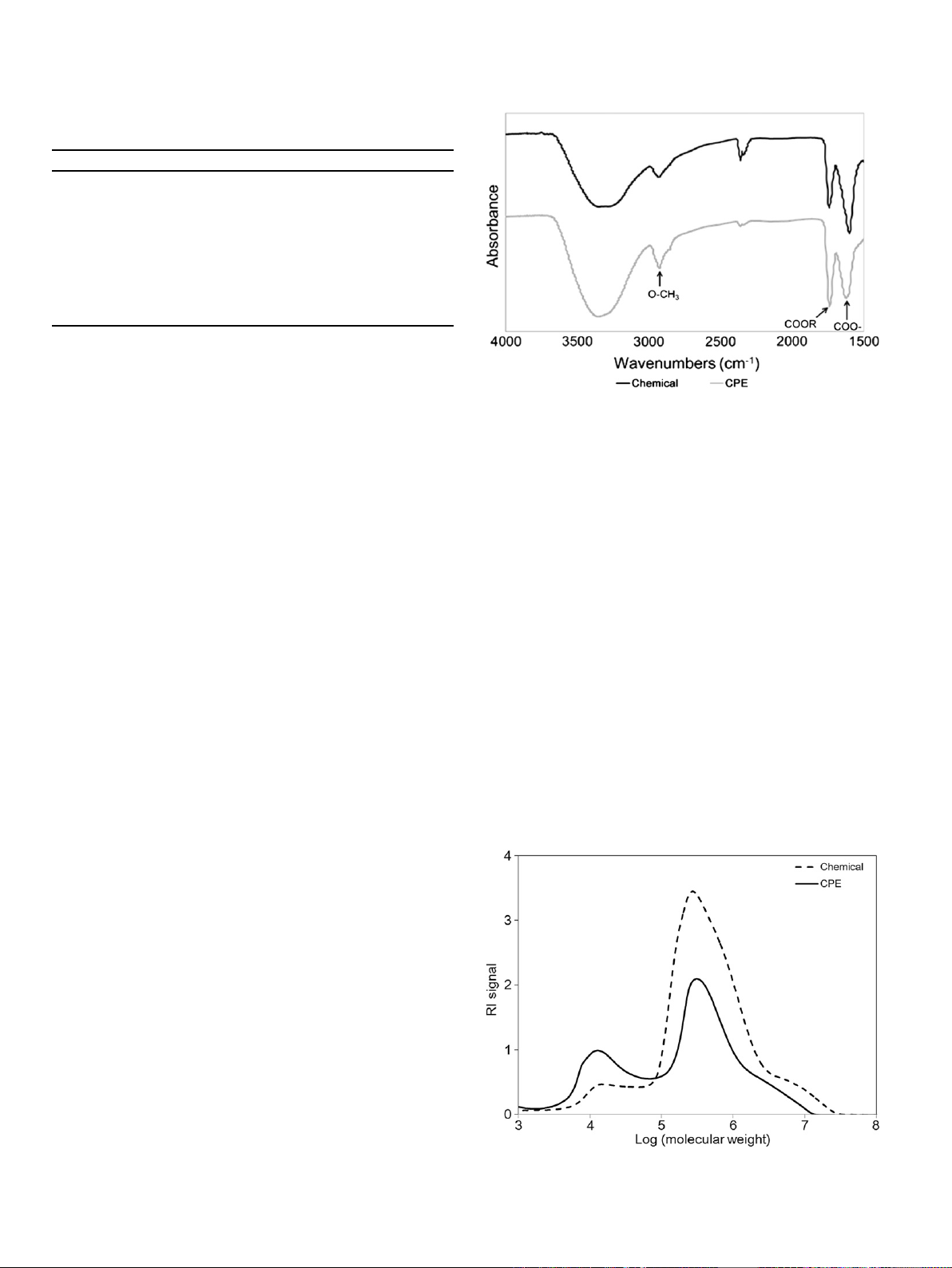

The molecular weight distribution of pectin was investigated by

HPSEC with pullulans as standards. As shown in Fig. 2, both pectin

samples showed a major peak of molecular weight distribution

which was determined to be around 270 kDa. Also, a minor peak

(190 kDa) was observed in the lower molecular weight range which

became more pronounced in the pectin extracted by the CPE

treatment. Thus, it seemed that the chains of pectin molecules were

partially degraded by the cell wall degrading enzyme used in this

study.

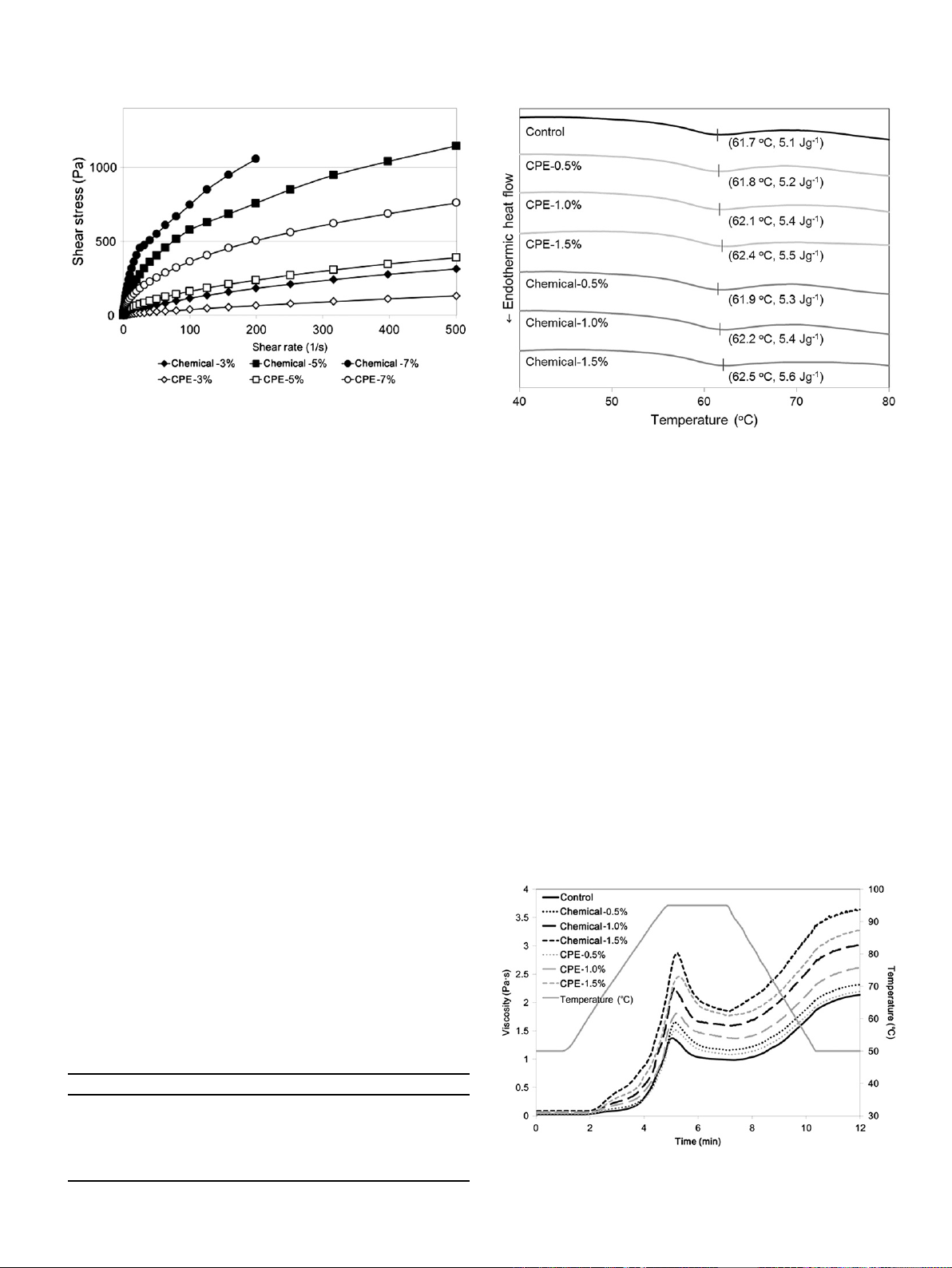

Fig. 3 exhibits the flow behaviors of pectin solutions under

steady-shear conditions, which were characterized by a plot of

stress versus shear rate. Overall, they showed a convex curvature

Fig. 1. FT-IR spectra of the pectin extracted in a chemical (Chemical) or combined

physicaleenzymatic (CPE) way.

Fig. 2. Molecular weight distribution of the pectin extracted in a chemical (Chemical)

or combined physicaleenzymatic (CPE) way.

Table 1

Chemical analysis of the pectin extracted in a chemical (Chemical) or combined

physicaleenzymatic (CPE) way.

Characteristics Chemical CPE

Yield (%) 8.0 0.2 7.3 0.4

Degree of esterification (%) 41.0 0.2 46.3 0.4

Galacturonic acid content (%) 72.3 1.2 54.5 0.9

Total neutral sugar (%) 11.1 0.9 17.6 1.4

Individual neutral sugar (%)

Fucose 0.1 0.0 0.1 0.0

Rhamnose 1.1 0.2 1.4 0.2

Arabinose 5.5 0.6 10.0 0.8

Galactose 3.0 0.4 4.3 0.7

Glucose 1.3 0.6 1.0 0.3

Xylose 0.1 0.0 0.8 0.2

J. Lim et al. / Food Hydrocolloids 29 (2012) 160e165162

with respect to the shear rate axis, which is typical of the fluids

with shear-thinning properties. However, the chemically-extracted

pectin exhibited higher values of stress than the pectin obtained by

the CPE method at the same concentration. It indicated the higher

apparent viscosity of the chemically-extracted pectin solutions

since viscosity is equal to the ratio of shear stress to shear rate.

Moreover, these flow curves were fitted to the Power-law equation

as follows,

s

¼K_

g

n

where

s

is shear stress (Pa), _

g

is shear rate (1/s), Kis consistency

index (Pa$s

n

), and nis flow behavior index (dimensionless). As

shown in Table 2, the consistency index, corresponding to the

viscosity at a shear rate of 1 s

1

, increased with increasing pectin

concentrations. In addition, the chemically-extracted pectin had

higher consistency index. The flow behavior index was less than the

unity, confirming that all of the pectin samples had shear-thinning

properties. However, lower values of the flow behavior index

indicated that the chemically-extracted pectin exhibited more

shear-thinning characteristics, compared with the pectin extracted

in a combined physicaleenzymatic way.

The effects of pectin on the thermodynamic properties of wheat

flour were investigated as shown in Fig. 4. The peak temperature of

starch gelatinization was 61.7

C for the control wheat flour and the

temperatures of the endothermic peaks were not affected by pectin

at 0.5% level. However, greater use of pectin tended to increase the

peak temperature. This is explained by the competition for water

between starch and pectin, raising the temperature of starch

gelatinization. A slight enthalpy increase was also observed with

increasing amounts of the pectin added. However, there seemed to

be no distinct difference in the thermodynamic properties of wheat

flour with pectins from the two extraction methods.

Fig. 5 exhibits the effect of pectin on the pasting properties of

wheat flour. As can be seen in Fig. 5, all of the samples showed the

typical pasting pattern of native starch during heating and cooling

cycles epeak viscosity, breakdown, and setback. During starch

gelatinization, starch in wheat flour hydrates and swells, losing

their crystalline structure. The swollen granules are closely packed

together, consequently leading to a viscosity increase (Lii, Shao, &

Tseng, 1995). A couple of preceding studies reported that the

swelling of starch granules was decreased in the

starchehydrocolloid system, weakening the close packing struc-

ture of swollen starch granules (Biliaderis, Arvanitoyannis,

Izydorczyk, & Prokopowich, 1997). Nonetheless, the use of pectin

gave rise to a dramatic viscosity increase with increasing pectin

content. Even, the peak viscosity at a level of 1.5% increased from

1.37 Pa$s to 2.87 and 2.46 Pa$s for the pectin extracted in chemical

and physicaleenzymatic ways, respectively. As mentioned above,

starch imbibes water during starch gelatinization, making less

water available for the pectin. Therefore, it would cause an increase

in the concentration of pectin which exists in continuous inter-

granular spaces, subsequently contributing to the increased

Fig. 3. Flow behaviors of the pectin extracted in a chemical (Chemical) or combined

physicaleenzymatic (CPE) way.

Table 2

Power-law parameters of the pectin extracted in a chemical (Chemical) or combined

physicaleenzymatic (CPE) way.

Extraction method Concentration (%) KnR

2

Chemical 3 5.2 0.67 1

5 53.29 0.51 0.99

7 92.13 0.47 0.99

CPE 3 1.23 0.75 1

5 11.86 0.56 1

7 39.52 0.48 1

Fig. 4. Changes in the temperature and enthalpy of starch gelatinization by the pectin

extracted in a chemical (Chemical) or combined physicaleenzymatic (CPE) way.

Fig. 5. Changes in the pasting property of wheat flour by the pectin extracted in

a chemical (Chemical) or combined physicaleenzymatic (CPE) way.

J. Lim et al. / Food Hydrocolloids 29 (2012) 160e165 163

viscosity. Additionally, the interaction between pectin and solubi-

lized starch might partly contribute to the increased viscosity. As

can be expected from the rheological results in Fig. 3, greater

viscosity increase was observed in the samples containing

chemically-extracted pectin. Moreover, the time of the peak

viscosity was delayed by the use of pectin, thus implying that pectin

affected the starch gelatinization temperature. This was in good

agreement with the DSC results (Fig. 4) and similar trends were

reported in the previous studies (Min, Bae, Lee, Yoo, & Lee, 2010;

Rojas, Rosell, & Benedito de Barber, 1999).

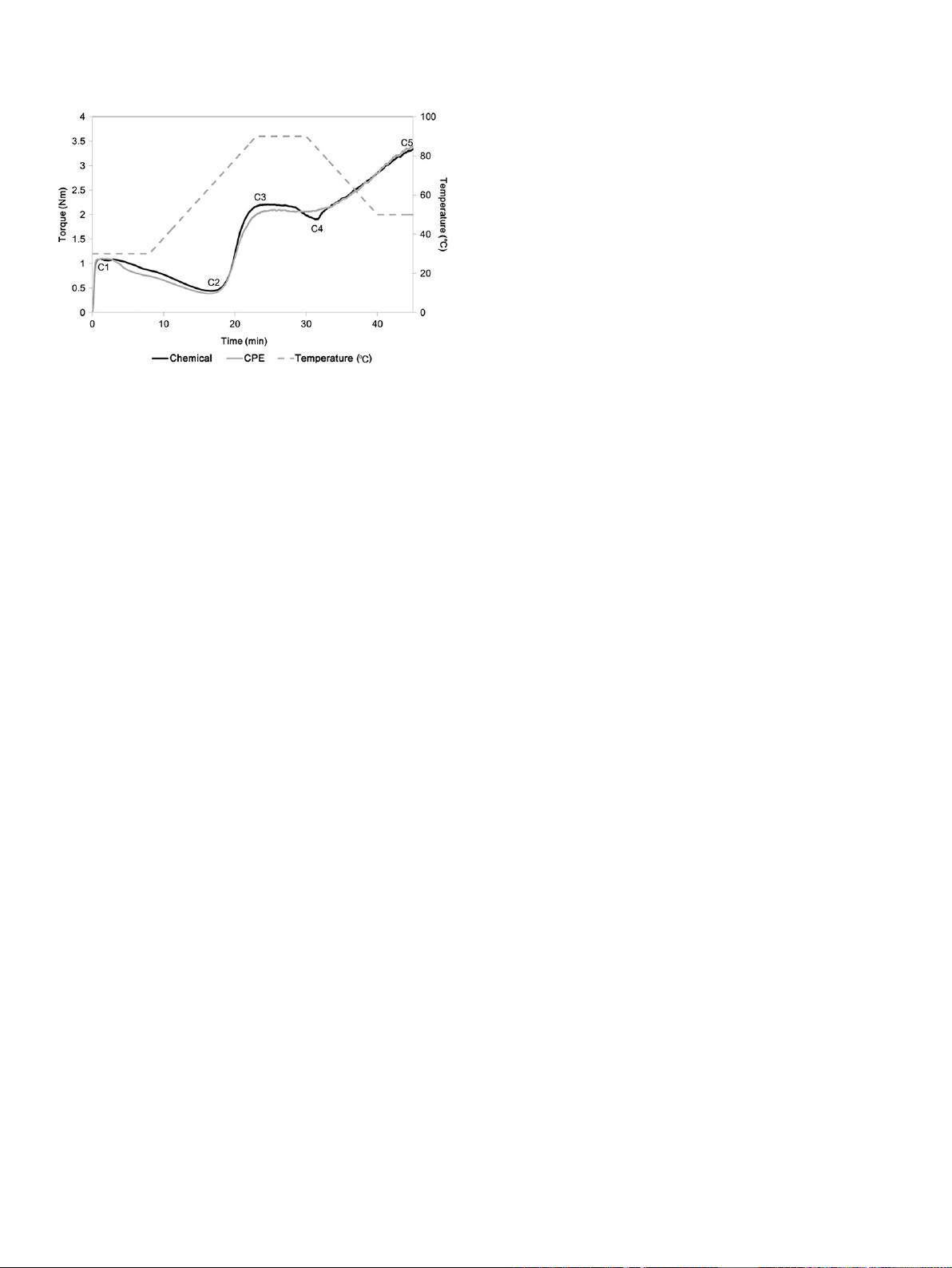

Fig. 6 exhibits the effect of pectin on the Mixolab curves of

wheat flour. In the Mixolab curve, there are five parameters to be

considered, which are maximum torque of the initial mixing stage

(C1), protein weakening (C2), starch gelatinization (C3), physical

breakdown of gelatinized starch granules (C4), and starch retro-

gradation (C5) (Kahraman et al., 2008). While the dough samples

were mixed under the condition of C1 ¼1.1 Nm, the water

absorption was 55.1% and 52.6% for the pectin obtained in chemical

and physicaleenzymatic ways, respectively. In the case of dough

stability, the use of chemically-extracted pectin produced dough

samples with greater resistance to deformation during over-mixing

as shown in the initial stage of the Mixolab curve (Fig. 6). A high

value of C2 indicated that more strong protein network was formed

in the dough containing chemically-extracted pectin. Moreover, as

manifested by C3, a greater degree of starch gelatinization could be

closely supported by the pasting property results in Fig. 5. Also, the

similar value of C5 suggests that there was no distinct difference in

the retardation of starch retrogradation in the wheat flour dough

system between both pectin samples.

4. Conclusions

Yuza pomace was subjected to combined physical and enzy-

matic treatment for producing pectin without any use of acidic

chemicals. Then, the physico-chemical, structural, and thermo-

mechanical properties of the extracted pectin were characterized

and compared with those of chemically-extracted pectin. The

results showed that low methoxyl pectin with 55% galacturonic

acid could be obtained by the combined physical/enzymatic

method without any use of chemicals, and its extraction yield was

7.3%. Both pectin solutions exhibited similar shear-thinning prop-

erties, while less viscosity was observed in the pectin obtained by

CPE treatment. In addition, when pectin was incorporated into

a wheat flour-water system, wheat flour had different patterns of

thermo-mechanical characteristics during mechanical shearing

and heating, depending on the pectin extraction method used.

This study demonstrated that pectin from Yuza pomace could be

obtained by a water-based extraction method without chemical

acids. Since consumer concerns about chemical additives have

grown, this study can contribute to the movement of the food

industry into the natural realm by eco-friendly processing tech-

nology with no harmful chemicals. This observation is also of great

significance as it contributes to process-saving and cost-effective

advantages derived from low cost treatment of wastewater.

Further efforts are needed to enhance the extraction yield and

purity of pectin and also to extend its practical use in a wider

variety of food products.

Acknowledgements

This work was carried out with the support of the “Cooperative

Research Program for Agriculture Science & Technology Develop-

ment (Project No. PJ907142)”Rural Development Administration,

Republic of Korea.

References

Biliaderis, C. G., Arvanitoyannis, I., Izydorczyk, M. S., & Prokopowich, D. J. (1997).

Effect of hydrocolloids on gelatinization and structure formation in concen-

trated waxy maize and wheat starch gels. Starch eStärke, 49,278e283.

Contreras-Esquivel, J. C., Voget, C. E., Vita, C. E., Espinoza-Perez, J. D., &

Renard, C. M. G. C. (2006). Enzymatic extraction of lemon pectin by endo-

polygalacturonase from Aspergillus niger.Food Science and Biotechnology, 15,

163e167.

FAO. (2010) FAOSTATeAgriculture Food and Agriculture Organisationof the United

Nations.

Fellah, A., Anjukandi, P., Waterland, M. R., & Williams, M. A. K. (2009). Determining

the degree of methylesterification of pectin by ATR/FT-IR: methodology opti-

misation and comparison with theoretical calculations. Carbohydrate Polymers,

78,847e853.

Garna, H., Mabon, N., Robert, C., Cornet, C., Nott, K., Legros, H., et al. (2007). Effect of

extraction conditions on the yield and purity of apple pomace pectin precipi-

tated but not washed by alcohol. Journal of Food Science, 72,C001eC009.

Gnanasambandam, R., & Proctor, A. (2000). Determination of pectin degree of

esterification by diffuse reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy.

Food Chemistry, 68,327e332.

Hwang, J. K., Kim, C. J., & Kim, C. T. (1998). Extrusion of apple pomace facilitates

pectin extraction. Journal of Food Science, 63,841e844.

Kahraman, K., Sakıyan, O., Ozturk, S., Koksel, H., Sumnu, G., & Dubat, A. (2008).

Utilization of Mixolab to predict the suitability of flours in terms of cake quality.

European Food Research and Technology, 227, 565e570.

Kim, I. C. (1999). Manufacture of citron jelly using the citron extract. Journal of the

Korean Society of Food Science and Nutrition, 28, 396e402.

Klavons, J. A., & Bennett, R. D. (1986). Determination of methanol using alcohol

oxidase and its application to methyl ester content of pectins. Journal of Agri-

cultural and Food Chemistry, 34,597e599.

Koley, T. K., Walia, S., Nath, P., Awasthi, O. P., & Kaur, C. (2011). Nutraceutical compo-

sition of Zizyphus mauritiana Lamk (Indian ber): effect of enzyme-assisted pro-

cessing. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition, 62,276e279.

Koubala, B. B., Kansci, G., Mbome, L. I., Crepeau, M. J., Thibault, J. F., & Ralet, M. C.

(2008). Effect of extraction conditions on some physicochemical characteristics

of pectins from “Améliorée”and “Mango”mango peels. Food Hydrocolloids, 22,

1345e1351.

Lii, C., Shao, Y., & Tseng, K. (1995). Gelation mechanism and rheological properties of

rice starch. Cereal Chemistry, 72, 393e400.

Liu, L., Cao, J., Huang, J., Cai, Y., & Yao, J. (2010). Extraction of pectins with different

degrees of esterification from mulberry branch bark. Bioresource Technology,

101, 3268e3273.

Min, B., Bae, I. Y., Lee, H. G., Yoo, S. H., & Lee, S. (2010). Utilization of pectin-enriched

materials from apple pomace as a fat replacer in a model food system. Bio-

resource Technology, 101,5414e5418.

Min, B., Lim, J., Ko, S., Lee, K. G., Lee, S. H., & Lee, S. (2011). Environmentally friendly

preparation of pectins from agricultural byproducts and their structural/rheo-

logical characterization. Bioresource Technology, 102, 3855e3860.

Oosterveld, A., Beldman, G., Schols, H. A., & Voragen, A. G. J. (2000). Characterization

of arabinose and ferulic acid rich pectic polysaccharides and hemicelluloses

from sugar beet pulp. Carbohydrate Research, 328,185e197.

Panchev, I., Kirchev, N., & Kratchanov, C. (1988). Improving pectin technology.

International Journal of Food Science and Technology, 23,337e341.

Park, S. M., Lee, H. H., Chang, H. C., & Kim, I. C. (2001). Extraction and physico-

chemical properties of the pectin in citron peel. Journal of the Korean Society of

Food Science and Nutrition, 30, 569e573.

Ptichkina, N. M., Markina, O. A., & Rumyantseva, G. N. (2008). Pectin extraction from

pumpkin with the aid of microbial enzymes. Food Hydrocolloids, 22,192e195.

Fig. 6. Thermo-mechanical properties of wheat flour dough containing the pectin

extracted in a chemical (Chemical) or combined physicaleenzymatic (CPE) way.

J. Lim et al. / Food Hydrocolloids 29 (2012) 160e165164

![Câu hỏi ôn tập Thức ăn chăn nuôi [năm hiện tại]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20250709/kimphuong1001/135x160/96231752221144.jpg)

![Đề cương ôn thi Phụ gia thực phẩm [năm hiện tại]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20251120/kimphuong1001/135x160/63671763608893.jpg)

![Đề cương ôn thi giữa kì môn Đánh giá cảm quan trong kiểm soát chất lượng [năm]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20251003/maihonghieu2004@gmail.com/135x160/69751759740815.jpg)

![Bài giảng Công nghệ chế biến và kiểm soát chất lượng thịt, thủy sản [mới nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20251001/123ngocdien/135x160/96891759397352.jpg)