http://www.iaeme.com/IJM/index.asp 6 editor@iaeme.com

International Journal of Management (IJM)

Volume 7, Issue 6, September–October 2016, pp.06–14, Article ID: IJM_07_06_002

Available online at

http://www.iaeme.com/ijm/issues.asp?JType=IJM&VType=7&IType=6

Journal Impact Factor (2016): 8.1920 (Calculated by GISI) www.jifactor.com

ISSN Print: 0976-6502 and ISSN Online: 0976-6510

© IAEME Publication

MODELING CUSTOMER SATISFACTION USING

STRUCTURAL EQUATION MODELING BASED ON

SERVICE QUALITY MEASUREMENT IN AIRLINE

INDUSTRY

Dr. M. SHIEK MOHAMED

Professor (Rtd), Jamal Institute of Management

Jamal Mohamed College, Tiruchirappalli.

S. AISHA RANI

Ph.D Research Scholar, Jamal Institute of Management

Jamal Mohamed College, Tiruchirappalli.

ABSTRACT

As the nature of services provided by airlines is a little different to other service industries,

additional research is needed to evaluate the service quality of airline services and its effects on

customer satisfaction using appropriate dimensions of service quality.

The service industry is one of the most important sectors these days, especially when

considering service quality as an important tool in enabling organizations to differentiate

themselves in a very challenging environment.

Customers expect personalized service, reliable employees and personal warmth in the service

delivery, and those elements will ultimately make the customers more satisfied with the service

purchased.

Key words: service quality, airline industry, customer satisfaction, quality of service.

Cite this Article: Dr. M. Shiek Mohamed and S. Aisha Rani, Modeling Customer Satisfaction

using Structural Equation Modeling Based on Service Quality Measurement in Airline Industry.

International Journal of Management, 7(6), 2016, pp. 06–14.

http://www.iaeme.com/IJM/issues.asp?JType=IJM&VType=7&IType=6

1. INTRODUCTION

Due to the fast-changing business environment, customer demands and expectations are also changing,

resulting in a situation where many of the service-providing companies – especially the airlines – have

failed to keep their fingers on the pulse of the true needs and wants of their passengers and still hold

outdated views of what airline services are all about. Airline companies think of passengers’ needs from

their own perspectives and usually focus on cost reductions to achieve efficient operations; however, this

may overlook the quality of the services provided to their customers.

Modeling Customer Satisfaction using Structural Equation Modeling Based on Service Quality Measurement in

Airline Industry

http://www.iaeme.com/IJM/index.asp 7 editor@iaeme.com

There is consensus in the marketing literature that better service quality is a critical success factor in

this era of intense competition (Tsoukatos and Mastrojianni, 2010). Due to the nature of services,

evaluation of service quality has been the subject of many studies. Service quality’s conceptual and

empirical link to customer satisfaction has turned it into a core marketing instrument (Ahmed, 2010).

Curiosity over the measurement of service quality is therefore high and researchers have devoted a great

deal of attention to service quality research (Abdullah, 2007). But the service quality of airlines has not

been thoroughly evaluated (Park, 2005). As the nature of services provided by airlines is a little different to

other service industries, additional research is needed to evaluate the service quality of airline services and

its effects on customer satisfaction using appropriate dimensions of service quality.

2. CUSTOMER SATISFACTION

Kotler (2000, p. 36) defined satisfaction as “a person’s feeling of pleasure or disappointment resulting

from comparing a product’s perceived performance (or outcome) in relation to his or her expectations”. It

is a key focus of research in many tourism studies due to its importance in determining the success and the

continued existence of the tourism business (Gursoy et al., 2007) and the benefits it brings to organizations

(Ali and Zhou, 2013; Amin and Nasharuddin, 2013; Weng and de Run, 2013; Ranaweera and Prabhu,

2003). The importance of customer satisfaction is derived from the generally accepted philosophy that for

a business to be successful and profitable, it must satisfy its customers (Shin and Elliott, 2001). Customer

satisfaction has been defined as a feeling of the post-consumption experienced by the customers

(Westbrook and Oliver, 1991; Um et al., 2006). In contrast to the cognitive focus of perceptions, customer

satisfaction is deemed an effective response to a product or service (Yuan, 2005). Previous research has

demonstrated that satisfaction is strongly associated with re-purchase intentions (Cronin and Taylor, 1992).

Customer satisfaction also serves as an exit barrier, helping a firm to retain its customers (Amin, 2013;

Liang and Zhang, 2012). In addition, customer satisfaction also leads to favourable word-of-mouth, which

provides a valuable form of indirect advertising to an organization (Park, 2005). Shin and Elliott (2001)

concluded that, through satisfying customers, organizations could improve profitability by expanding their

business and gaining a higher market share as well as repeat and referral business.

The concept of customer satisfaction and its implications in various industries have been somewhat

elusive due to the complex nature of people’s perceptions and evaluations (Ali et al., 2012; Amin and

Nasharuddin, 2013). For businesses in services industries, achieving customer satisfaction is far more

challenging. For instance, some services are extremely complex in nature and involve multiple service

encounter stages which have bearings on the level of overall customer satisfaction (Han and Ryu, 2009). In

the context of studies on airlines companies, Archana and Subha (2012) state that airline service quality

dimensions – i.e., in-flight services, in-flight digital services, and airline back-office operations – are

significant predictors of passengers’ satisfaction and that this satisfaction influences their loyalty and the

airline’s image. Similarly, Abdullah (2007) also found a positive relationship between satisfaction and both

future use of the airline and the likelihood of recommending it to others. Therefore, in the airline industry,

passengers’ satisfaction plays an important role in measuring the quality of services and the likelihood that

they will continue their relationship with the service providers (Archana and Subha, 2012; Lau, 2011;

Abdullah et al., 2007).

3. SERVICE QUALITY

Service quality is defined as “a function of [the] difference between [the] service expected and [the]

customer’s perceptions of the actual service delivered” (Parasuraman, 1988, p. 13) and it has received

intense research attention in services marketing (Caro and Garcia, 2007; Wu and Ko, 2013). A great deal

of attention has been given to its measurement and conceptualization (Ali, 2013; Amin, 2013). An initial

conceptualization of service quality was discussed by Parasuraman et al. (1985) as a function of the

difference between service expectations and customers’ perceptions of the actual service delivered. They

Dr. M. Shiek Mohamed and S. Aisha Rani

http://www.iaeme.com/IJM/index.asp 8 editor@iaeme.com

suggested that customers perceive the relative quality of services by comparing the actual performance of

the firm with their own expectations, shaped by experience, word-of-mouth communications, and/or

memories (Tsoukatos and Mastrojianni, 2010); this comparison is referred to as perceived service quality

(Parasuraman et al., 1988). In this context, Zeithaml et al. (1996) posited that better understanding of

customers’ expectations is significant in delivering quality services.

In terms of service quality measurement, Parasuraman et al. (1985) proposed a model with ten

dimensions, including tangibles, reliability, responsiveness, understanding the customers, access,

communication, credibility, security, competence and courtesy. This model was later modified by

Parasuraman et al. (1988) and named the SERVQUAL scale, which included five dimensions: tangibles,

reliability, responsiveness, assurance and empathy. The SERVQUAL scale has been widely applied by

both academics and practitioners across industries in different countries (Ali et al., 2013; Wu and Ko,

2013). It provides a comprehensive measurement scale for perceived service quality andhas practical

implications (Ali et al., 2012; Amin et al., 2013; Parasuraman et al., 1994; Angur et al., 1999).While

SERVQUAL has been widely adopted by scholars in the airline industry (Gilbert and Wong, 2003; Park et

al., 2005), it has also been criticised, as it compares customers’ expectations with customers’ perceptions

of the services received (Buttle, 1996; Cronin and Taylor, 1992; Robledo, 2001). Wu and Ko (2013) also

suggested that SERVQUAL provides a general guideline for service quality assessment in most of the

service contexts; however, its factors ought to be examined and determined in relation to industry-specific

issues. In this regard, Park et al. (2005) postulated that the particular issues pertaining to the airline

industry (e.g. ticketing, luggage allowance, on-board facilities) would be different from those of other

service industries. Various researchers studying the airline industry observed that in this industry,

customers’ expectations are shaped at the “moment of- truth” by the reservations department of the airline,

telephone sales, ticketing, cabin crew, cabin services, baggage handling, flight schedules, and others

(Archana and Subha, 2012; Saha and Theingi, 2009; Nadiri et al., 2008; Ekiz et al., 2006; Prayag, 2007),

and Park et al. (2005) noted that the five-dimension 22-item SERVQUAL scale is not applicable to the

airline industry because it does not consider industry- (i.e. airline) specific aspects of service quality.

Because of the huge criticism of the application of the SERVQUAL scale, several researchers have

used another service quality measurement scale, developed by Cronin and Taylor (1992), which is known

as SEVPERF. This model only considers customers’ perceptions of service provider’s performance to

assess service quality (Cronin and Taylor, 1994). This scale has proved to be a better tool to measure

service quality in the airline industry, but it has also been criticized for assessing customer satisfaction

related to a specific transaction (Ostrowski et al., 1993). However, some scholars have also accused

SERVPERF of being too generic and failing to capture industry-specific dimensions underlying

passengers’ perceptions of quality in the airline industry (Cunningham et al., 2004).

Consequently, a number of scholars have tried to propose models with dimensions of service quality

that are specific to the airline industry (e.g. Gourdin, 1988). For example, a model presented by Gourdin

(1988) categorised airline service quality into three aspects: price, safety, and timeliness. Similarly,

Ostrowski et al. (1993) looked at timeliness, food and beverage quality and comfort of seats in order to

evaluate the cleanliness of seats, food and beverage quality, and customer complaints handling as the

dimensions for measuring service quality, whereas Chang and Yeh (2002) revised the five aspects of

service quality presented by Parasuraman et al. (1988), namely tangibility, reliability, responsiveness,

assurance, and empathy. Park et al. (2005) also assessed airline service quality using three dimensions,

namely reliability and customer service, convenience and accessibility, and in-flight service. A recent

study conducted by Namukasa (2013) considered reliability, responsiveness and discounts as dimensions

of pre-flight service quality, tangibles, courtesy, and language skills as dimensions of in-flight service

quality and frequent flyer programmes and timeliness as dimensions of post flight service quality when

assessing service quality in the Ugandan airline industry. Their findings indicated that pre-flight, in-flight

and post-flight services had a significant effect on passenger satisfaction. Moreover, Wu and Cheng (2013)

adopted a hierarchical structure and classified airline service quality into four primary dimensions, namely

Modeling Customer Satisfaction using Structural Equation Modeling Based on Service Quality Measurement in

Airline Industry

http://www.iaeme.com/IJM/index.asp 9 editor@iaeme.com

interaction quality, physical environment quality, outcome quality, and access quality, with 11 sub-

dimensions, namely conduct, expertise, problem solving, cleanliness, comfort, tangibles, safety and

security, waiting time, valence, information, and convenience. They found that their measurement scale

was psychometrically sound; however, the theoretical and conceptual basis for understanding the nature of

passengers’ perceptions of service quality in the airline industry is still in the developmental stage.

4. SERVICE QUALITY AND CUSTOMER SATISFACTION

Scholars view service quality as an antecedent of customer satisfaction (Amin et al., 2013; Parasuraman,

1985, 1988; McDougall and Levesque, 2000). In the airline industry, Saha and Theingi (2009) found a

significant relationship between airline service quality and passenger satisfaction, meaning that the higher

the perceived service quality, the higher was the passenger satisfaction (Lau, 2011). On the contrary, when

a customer is not satisfied, he or she is more likely to switch to another airline and to not recommend the

airline to friends or family members (Abdullah, 2007).

Despite the general agreement on the definitions of perceived service quality and satisfaction, their

causal relationship is yet to be resolved (Saha and Theingi, 2009). Some researchers have suggested

customer satisfaction to be an antecedent of perceived service quality (Bolton and Drew, 1991; Bitner,

1990), whereas others consider perceived service quality as an antecedent of customer satisfaction (Oliver,

1997; Cronin and Taylor, 1992; Parasuraman, 1988). In support of this view, Han, (2008) confirmed the

antecedent role of service quality with respect to customer satisfaction in various service industries

(airlines, banks, beauty salons, hospitals, hotels, mobile telephones). This study also adopts the second

school of thought and thus hypothesizes that airline service quality significantly influences passengers’

satisfaction.

5. OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

• To study the selected personal profiles of the respondents and their association with customer satisfaction in

Airline Services.

• To measure the airline service quality dimensions.

• To identify the level of customer satisfaction towards Airline Services

• To predict the impact of Airline service quality dimensions towards customer satisfaction.

6. HYPOTHESES

• There is no association between selected personal profiles of the respondents and customer satisfaction.

• The Airline Service Quality dimensions create positive impact towards customer satisfaction.

7. METHODOLOGY

The study is descriptive and correlation in Nature. In this study survey instrument has been adopted and

conducted among the passengers travelled from Tiruchirappalli airport in Indian Airlines. To measure the

airline service quality, the dimensions like Airline Tangibles, Terminal Tangible, Personnel Quality,

Empathy and Airline Image was considered. All the above mentioned airline service quality dimensions

source was adopted from AIRQUAL Model presented by Ekiz (2006). The dimension customer

satisfaction was measure by five individual statements, which was proposed by Westbrook and Oliver

(1991). A five point likert scale was used to measure the perception of customers (Passengers) to measure

the service quality dimensions and customer satisfaction. The study was pre-tested with 30 customers who

regularly travel in Indian Airlines. Based on their suggestions few changes were made in the questionnaire.

The objective of the study is to predict the level of customer satisfaction based on Airline Service

Quality dimensions. To attain the objective of the study, the passengers travelled by Air India from

Tiruchirappalli airport in the last three months (May to July 2016) are considered as the population. The

Dr. M. Shiek Mohamed and S. Aisha Rani

http://www.iaeme.com/IJM/index.asp 10 editor@iaeme.com

purpose of the study is explained to the customers in the waiting lounge, after accepting to participate in

the research, the questionnaire was distributed to the respondents. A total of 405 questionnaires were

distributed, in which 382 were returned, in which only 320 were at fully usable state. Thus response rate

for the study is high (79%).

8. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

8.1. Test Statistics – Chi-Square

To identify the association between Gender and Educational Qualification with customer satisfaction chi

square test was used. The Chi square value (3.386), df (4) and p-value (.495) shows that there is no

association between gender and customer satisfaction. The Chi square value (17.346), df (12) and p-

value (.137) shows that there is no association between educational qualification and customer satisfaction.

The selected personal profiles gender and educational qualification shows that there is no association with

customer satisfaction, based on the test statistics, chi square values.

To identify the significant relationship between age and monthly income with customer satisfaction,

the test statistics ANOVA was used. The f- Value (.906), df (3) and sig value (.439) shows that there is no

significant relationship between age and customer satisfaction. The F-Value (.756), df (4) and sig (.555)

shows that there is no significant relationship between monthly income and customer satisfaction.

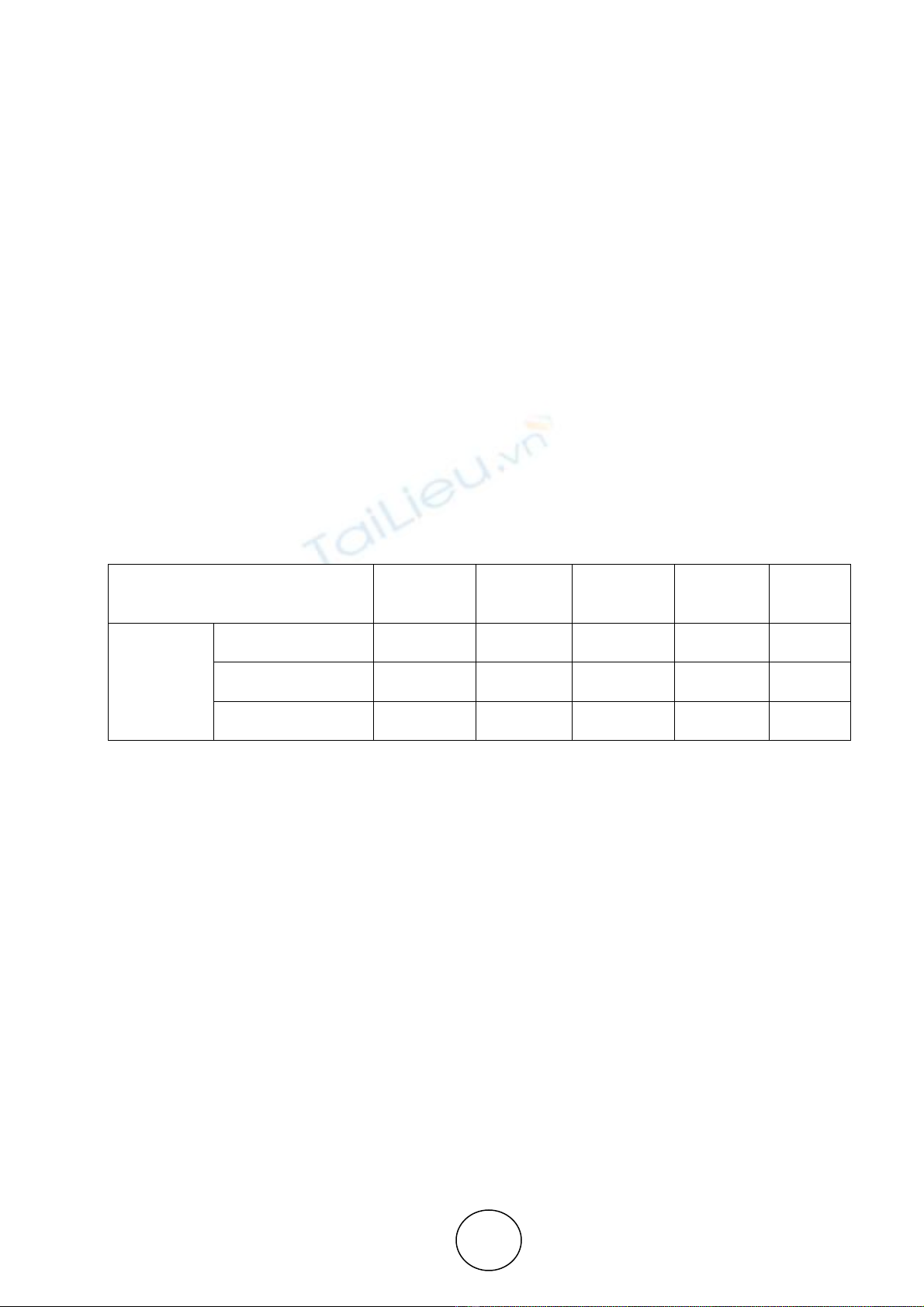

8.2. Relationship between Airline Service Quality Dimensions and Customer Satisfaction

Airline

Tangibles

Terminal

Tangible

Personnel

Quality Empathy Airline

Image

Customer

Satisfaction

Pearson Correlation .556

**

.539

**

.479

**

.538

**

.527

**

Sig. (2-tailed) .000 .000 .000 .000 .000

N

320 320 320 320 320

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed).

To identify the strength of relationship between the Airline service quality dimensions (Airline

Tangibles, Terminal Tangible, Personal Quality, Empathy and Airline Image) and customer satisfaction,

correlation test was used in this study.

The above table shows that Customer satisfaction is positively highly correlated (.556) with Airline

Tangibles and it is highly significant at (.000) level. The Airline service quality dimensions Terminal

Tangibles (.539), Empathy (.538) and Airline Image (.527) are highly significantly correlated with

Customer satisfaction. The dimension Personal quality (.479) founds to be moderately correlated with

Customer satisfaction.

![Công Ước Hàng Không Dân Dụng Quốc Tế: [Thông tin chi tiết/Hướng dẫn/Phân tích]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2012/20121016/ruavanguom/135x160/1451350381899.jpg)

![Bài giảng Nguyên lý marketing Chương 9: Trường ĐH Kinh tế, HN [chuẩn nhất]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2025/20250514/antrongkim2025/135x160/37641768462871.jpg)