REVIEW ARTICLE

Structures of human proteinase 3 and neutrophil

elastase – so similar yet so different

Eric Hajjar

1

, Torben Broemstrup

2,3

, Chahrazade Kantari

4

,Ve

´ronique Witko-Sarsat

4,5

and Nathalie Reuter

3,6

1 Dipartimento di Fisica, University of Cagliari (CA), Italy

2 Department of Informatics, University of Bergen, Norway

3 Computational Biology Unit, BCCS, University of Bergen, Norway

4 Inserm, U845 and U1016, Paris, France

5 Institut Cochin, Universite

´Paris Descartes, CNRS (UMR 8104), France

6 Department of Molecular Biology, University of Bergen, Norway

Introduction

Human neutrophil elastase (hNE), human cathepsin G

(hCatG) and human proteinase 3 (hPR3) (also termed

myeloblastin [1] and p29b [2]) are serine proteases

mostly expressed in polymorphonuclear neutrophils,

but also are found in monocytes. All three enzymes

are homologous, although hNE and hPR3 share 56%

Keywords

human neutrophil elastase; inflammation;

myeloblastin; neutrophil, proteinase 3;

vasculitis; Wegener granulomatosis

Correspondence

N. Reuter, Department of Molecular

Biology, University of Bergen,

Thormohlensgt 55, N-5008 Bergen, Norway

Fax: +47 555 84295

Tel: +47 555 84040

E-mail: nathalie.reuter@mbi.uib.no

(Received 22 January 2010, revised 11

March 2010, accepted 18 March 2010)

doi:10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07659.x

Proteinase 3 and neutrophil elastase are serine proteinases of the polymor-

phonuclear neutrophils, which are considered to have both similar localiza-

tion and ligand specificity because of their high sequence similarity.

However, recent studies indicate that they might have different and yet

complementary physiologic roles. Specifically, proteinase 3 has intracellular

specific protein substrates resulting in its involvement in the regulation of

intracellular functions such as proliferation or apoptosis. It behaves as a

peripheral membrane protein and its membrane expression is a risk factor

in chronic inflammatory diseases. Moreover, in contrast to human neutro-

phil elastase, proteinase 3 is the preferred target antigen in Wegener’s gran-

ulomatosis, a particular type of vasculitis. We review the structural basis

for the different ligand specificities and membrane binding mechanisms of

both enzymes, as well as the putative anti-neutrophil cytoplasm autoanti-

body epitopes on human neutrophil elastase 3. We also address the differ-

ences existing between murine and human enzymes, and their consequences

with respect to the development of animal models for the study of human

proteinase 3-related pathologies. By integrating the functional and the

structural data, we assemble many pieces of a complicated puzzle to pro-

vide a new perspective on the structure–function relationship of human

proteinase 3 and its interaction with membrane, partner proteins or cleav-

able substrates. Hence, precise and meticulous structural studies are essen-

tial tools for the rational design of specific proteinase 3 substrates or

competitive ligands that modulate its activities.

Abbreviations

a1-PI, a1-proteinase inhibitor; ANCA, anti-neutrophil cytoplasm autoantibody; hNE, human neutrophil elastase; hPR3, human proteinase 3;

human cathepsin G, hCatG; mbPR3, membrane hPR3; PR3, proteinase 3.

2238 FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 2238–2254 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS

sequence identity for the mature enzymes, whereas

their similarity to hCatG is approximately 35%. Neu-

trophil serine proteinases are considered to be crucial

elements in neutrophil effector mechanisms [3,4]. Using

knockout mice invalidated for either hNE or hCatG, it

has been clearly demonstrated that both enzymes are

required for complete and adequate microbicidal activ-

ity [5,6]. Despite the lack of hPR3 knockout mice, a

similar function has been assigned for PR3 [2]. In

addition, it is now clear that these enzymes are also

involved in non-infectious inflammatory processes and

cell signaling [7,8]. A salient feature of hPR3 is its

identification as the main target antigen of the anti-

neutrophil cytoplasm autoantibodies (ANCA) in a

particular type of vasculitis, the Wegener’s granuloma-

tosis, which is a systemic inflammatory disease involv-

ing the lung, skin and kidney. The mechanisms

underlying this specific autoimmunization against

hPR3, and not against its homologs such as hNE, are

still unknown [9]. Because of the high sequence similar-

ity between hNE and hPR3, the substrate specificity

and the resulting functions of hPR3 have often been

extrapolated from the available data on hNE.

Together with the lack of structural and biophysical

studies on hPR3, relative to hNE, this has contributed

to a functional annotation of hPR3 that is too simplis-

tic. In recent years, however, more attention has been

paid to the structural properties of PR3 [10–14]. A bet-

ter understanding of the structure–function relation-

ship of the enzyme will contribute to the elucidation of

its original functions and help with the design of spe-

cific substrates for one or the other enzyme. So far, the

identification of the presence and hence the respective

role of either hPR3 or hNE in complex biological

models (both in vitro and in vivo) is impaired by a lack

of reliable specific inhibitors.

We review the sequence and structural data available

on both enzymes and highlight their similarities and

differences. We then summarize and discuss the latest

findings on three particular aspects of hPR3: ligand

specificity, membrane binding and putative ANCA

epitopes. We also address the similarities and differ-

ences between murine and human enzymes, and their

consequences with respect to the development of

animal models for the study of human PR3-related

pathologies.

PR3 and NE are highly similar

chymotrypsin-like serine proteases

All serine proteases are named after the nucleophilic

serine in their active site. The family of serine prote-

ases comprises four distinct clans, named after

proteins representative of each clan: chymotrypsin,

subtilisin, carboxypeptidase Y and caseinolytic prote-

ase [15]. PR3 and NE are chymotrypsin-like serine

proteases. Despite the absence of any conservation of

secondary or tertiary structure elements, the four

clans of serine proteases all have the same active site

consisting of three amino acids: His, Asp and Ser.

The relative orientation of the histidine, serine and

aspartic acid is similar in all clans and results in the

formation of strong hydrogen bonds between histi-

dine and serine on the one hand, and histidine and

aspartic acid on the other hand. By convention, in

chymotrypsin-like serine proteases, the histidine,

aspartic acid and serine are numbered 57, 102 and

195, respectively. The reaction mechanism is illus-

trated in Fig. 1A. The substrate is positioned opti-

mally in the active site as a result of a network of

interactions that extends on both sides of the cleav-

able bonds. The interactions sites are named using

the Schechter and Berger nomenclature [16]. The rec-

ognition or subsites of the enzyme are Sn, …S1,

S1¢,…Sn¢and, for the corresponding peptide,

Pn, …P1, P1¢,…Pn¢, where P1-P1¢is the cleavable

peptide bond (Fig. 1B).

The sequences of the hNE (EC 3.4.21.37) [17–20] and

hPR3 (EC 3.4.21.76) [21–23] are shown in Fig. 2A,

where we use bovine chymotrypsinogen A numbering.

This numbering convention is used throughout the

present review (for correspondence with other number-

ing schemes, see Table S1).

hPR3 and hNE are synthesized as inactive zymogens

of 256 and 267 amino acids, respectively. These pre-

proforms undergo four consecutive steps that lead to

the mature enzymes [24–28]. The signal peptides (27

and 29 amino acids for hPR3 and hNE, respectively;

light blue boxes in Fig. 2A) are removed to yield the

proforms. The hPR3 proform is then glycosylated on

amino acids Asn113 and Asn159, and hNE on Asn

109 and Asn159 (green stars in Fig. 2A). Subse-

quently, the N-terminal dipeptide (AE for hPR3, SE

for hNE; light green boxes in Fig. 2A) is cleaved by a

cysteine protease, cathepsin C. The cleavage of the

dipeptide leads to a structural rearrangement of the

N-terminal region, which, from an extended solvent-

exposed conformation, becomes inserted into the pro-

tein core and interacts with Asp194. The enzymes then

become catalytically active. The fourth step is the

cleavage of the C-terminal pro-peptides (orange boxes

in Fig. 2A).

hPR3 and hNE are homologous and their mature

forms, comprising 221 and 218 amino acids, respec-

tively, share 56% sequence identity. Conserved resi-

dues are spread rather equally along the sequences.

E. Hajjar et al. Structure–function relationship of PR3 versus NE

FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 2238–2254 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS 2239

Fold and surface properties

X-ray data

Like all chymotrypsin-like serine proteases, hPR3 and

hNE adopt a fold consisting of two b-barrels made

each of six anti-parallel b-sheets (Fig. 2B). The struc-

tures of the mature forms of the human enzymes were

revealed by X-ray crystallography in the late 1980s for

hNE, and some years later for hPR3. To date, there

are seven structures of hNE deposited in the Protein

Data Bank (PDB code: 1B0F [29], 1H1B [30], 1HNE

[31], 1PPF [32], 1PPG [33], 2RG3 [34] and 2Z7F [35])

and one of hPR3 (1FUJ [36]). No structures of NE or

PR3 from other species are available (only computa-

tional models of the murine species have been

described) [11,14], nor are structures of the proforms.

hNE crystals all contain monomers (1B0F, 1HNE,

1PPF, 1PPG, 2RG3 and 2Z7F) or dimers (1H1B),

whereas hPR3 was crystallized as a tetramer, which

can be regarded as a dimer of dimers; two monomers

in a dimer are oriented so that their active sites face

each other, preventing the binding of large substrates.

Moreover, the hole in the middle of the tetramer is

lined with hydrophobic residues. This characteristic of

the crystals of hPR3 has not been observed in the case

of hNE, although it might be related to an increased

propensity of monomeric hPR3 to interact with hydro-

phobic environments through this region. Both hPR3

and hNE contain the same four disulfide bridges

between cysteine pairs 42–58, 136–201, 168–182 and

191–220.

The overall structural differences between hNE and

hPR3 are very small. The rmsd, calculated after struc-

tural alignment with stamp [37], on C-alpha atoms of

hPR3 and all seven available hNE structures is below

1A

˚and the structural difference between the seven

hNE structures is in the range 0.3–0.6 A

˚. The loop

between extended sheets 1 and 2 (amino acids 36–39)

is the only region showing a significantly larger struc-

tural variation as a result of the insertion of three resi-

dues (NPG) in hPR3 (Fig. 2A).

Different glycosylation sites

Most structures of hNE (1B0F, 1H1B, 1PPF, 1PPG

and 2Z7F) reveal the presence of two sugar moieties

on both Asn109 and Asn159, whereas one of the latest

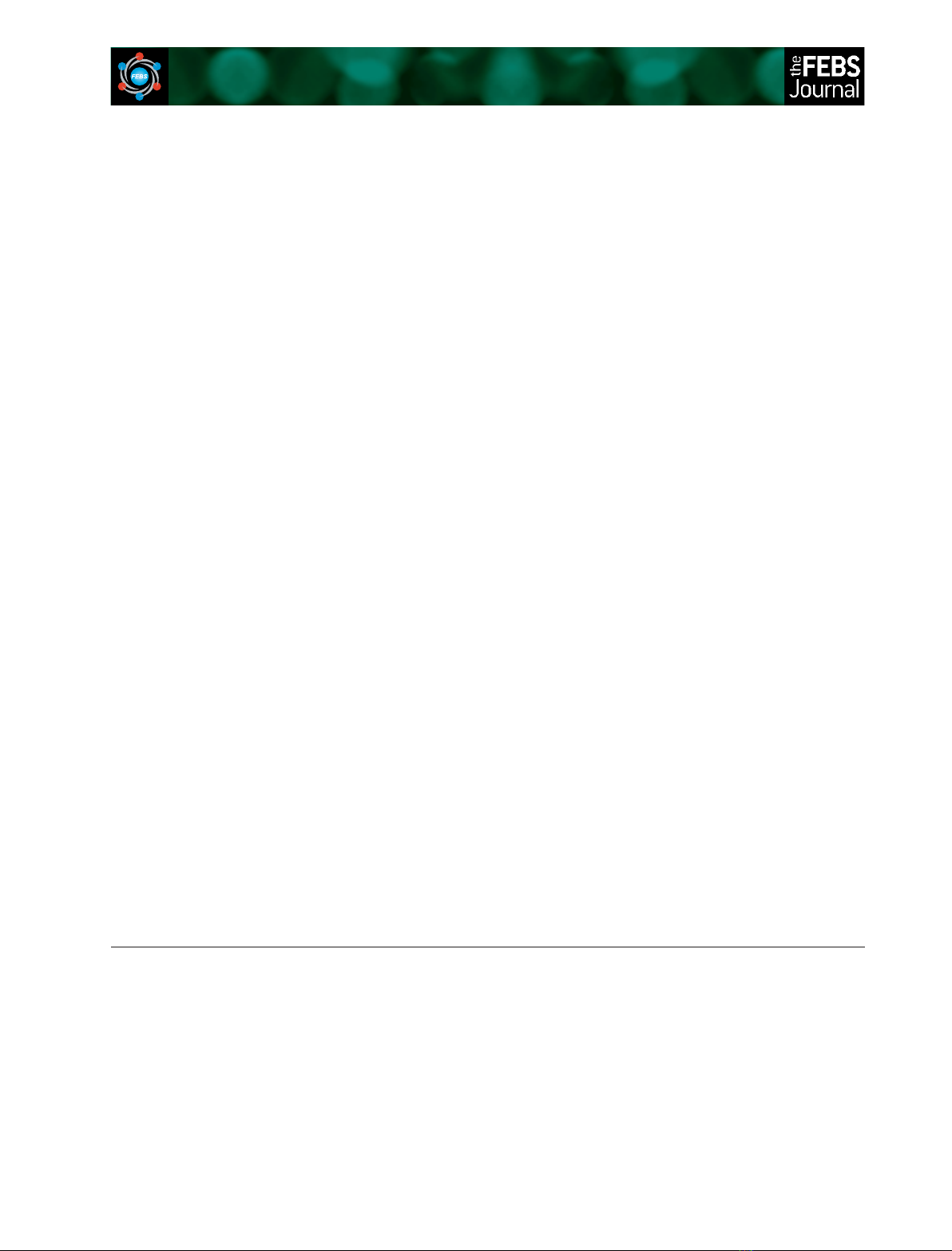

A

B

P1′P2′

Fig. 1. (A) Reaction mechanism of serine

proteases. (1) The first step of the catalytic

reaction, after the formation of the enzyme–

substrate or Michaelis complex, is the acyla-

tion step; it starts with the attack of the

catalytic serine on the carbonyl group of the

cleavable amide bond and the transfer of

the hydroxyl hydrogen of the serine to the

histidine. (2) This leads to the release of the

C-terminal end of the substrate and the

formation of a covalent intermediate (i.e. the

acyl enzyme) between the enzyme and the

N-terminal part of the substrate. (3) The

second step of the reaction (termed deacyl-

ation) starts with the attack of a nucleophilic

water on the substrate carbonyl and

(4) ends with the release of the N-terminal

part of the substrate, when the catalytic

triad is regenerated. The nitrogen atoms of

residues Gly193 and Ser195 stabilize the

so-called oxyanion hole. (B) Schechter and

Berger convention for the numbering of

enzyme-ligand binding sites.

Structure–function relationship of PR3 versus NE E. Hajjar et al.

2240 FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 2238–2254 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS

structures shows only one occupied site (Asn159 for

2RG3). In the structure of hPR3, only one glycolysa-

tion site (Asn159 and not Asn113) is occupied by a

sugar. All three glycosylation sites (Asn109, Asn113

and Asn159) are remote from the catalytic triad and

the ligand binding sites (Figs 3 and 4A). According to

Specks et al. [38], both sites are occupied in neutrophil

hPR3, although they have different functional signifi-

cance; glycosylation on Asn159 influences hPR3

thermostability and increases significantly the catalytic

activity measured on a small peptidic substrate

(N-methoxysuccinyl-Ala-Ala-Pro-Val), whereas glyco-

sylation on Asn113 appears to be important (but

is not an absolute requirement) for an efficient

N-terminal processing of hPR3. Interestingly, of both

glycosylation sites, Asn113 is the furthest away from

the N-terminal end of hPR3, as observed from the

structure of the mature form. Unfortunately, no

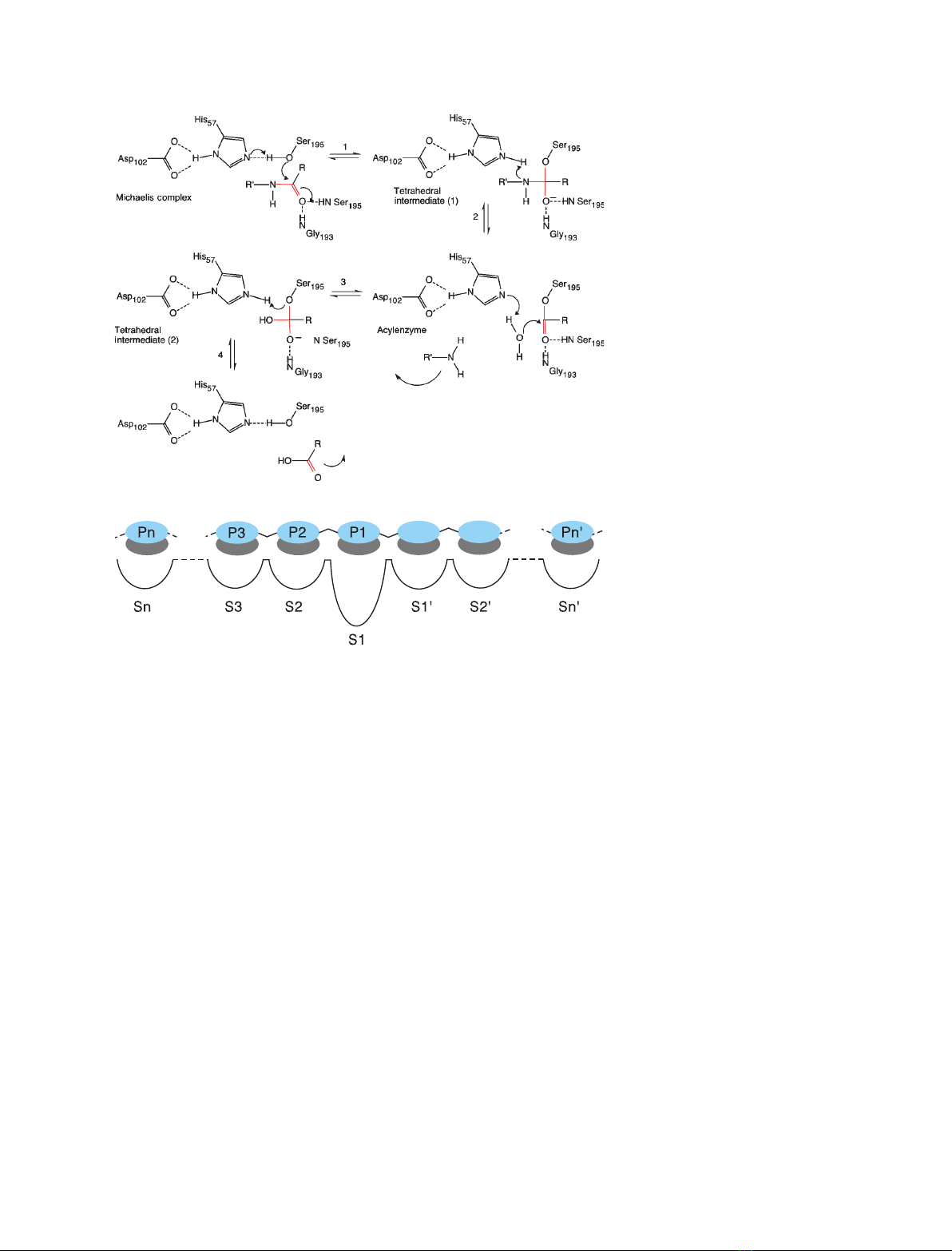

A

B

Fig. 2. Sequence alignment and superimpo-

sition of the 3D structures of hNE and hPr3.

(A) Sequence alignment. The numbering

follows the chymotrypsin convention. Amino

acids present in the proforms are

highlighted with boxes of different colors:

signal peptides, blue; N-terminal dipeptides,

green; C-terminal propeptides, orange.

Green stars are used to highlight the amino

acids of the catalytic triad (His57, Asp102,

Ser195), whereas orange stars highlight the

glycosylation sites. The secondary structure

elements are conserved in both proteins

and are represented below the sequences

(pink arrows, extended strands; yellow

cylinders, helices). The extended strands

constituting the b-barrels are numbered 1–6

and 7–12 for the first and second barrels,

respectively. (B) Superimposition of the 3D

structures of hPr3 (1FUJ) [36] and hNE

(1PPF) [32]. Secondary structure elements

are colored as shown in Fig. 1. The catalytic

triad is represented in green balls and

sticks. Two cylinders (black lines) represent

the limits of the two b-barrels.

E. Hajjar et al. Structure–function relationship of PR3 versus NE

FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 2238–2254 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS 2241

structure of any of the proforms of hPR3 or hNE is

available, although X-ray structures of proforms of

homologues have been reported (pro-granzyme K,

1MZA [39], chymotrypsinogen, 2CGA [40], and tryp-

sinogen, 2TGT [41]), where it can be clearly seen that

the N-terminal end (residues 14–17) freely extends out

of the core of the protein along the extended sheet

containing residue 159 (extended sheet numbered 8

in Fig. 3). Residue 159 in chymotrypsinogen and

pro-granzyme K is thus very close to the extended

N-terminal segment.

Different surface properties

Earlier studies have questioned the relationship

between the net charge difference and the functions

of PR3 and NE [36,42]. Indeed, at neutral pH, hNE

has a net charge of +10 (it contains 19 arginines and

only nine acidic residues), whereas hPR3 has a much

lower net charge of +2, although it contains approxi-

mately the same number of charged amino acids as

hNE. The sequence of the mature form contains 13

arginines, two lysines, ten aspartic acids and four

glutamic acids. Fujinaga et al. [36], as well as

subsequent in silico pK

a

calculations [10,43], suggest

Asp213 to be protonated. The availability of the

enzymes atomistic structures allows the calculation of

the electrostatic surface potential (i.e. the electrostatic

potential created by all the amino acids of the

enzyme in its vicinity) (Fig. 5). It is a critical determi-

nant of its surface properties and it is more relevant

to its structure–activity relationship because it reflects

not only the net charge, but also the charge distribu-

tion. Electrostatic interactions are known to play a

key role in macromolecular interactions (e.g. with

partner proteins, ions or membrane binding); thus,

they might explain protease-specific functions. Inter-

estingly, in the case of hNE, there is an omnipresence

of electropositive potential that covers most of the

surface of the enzyme, except at the substrate-binding

site. This is not the case for hPR3, where electroposi-

tive clusters (or ‘patches’) alternate with negative and

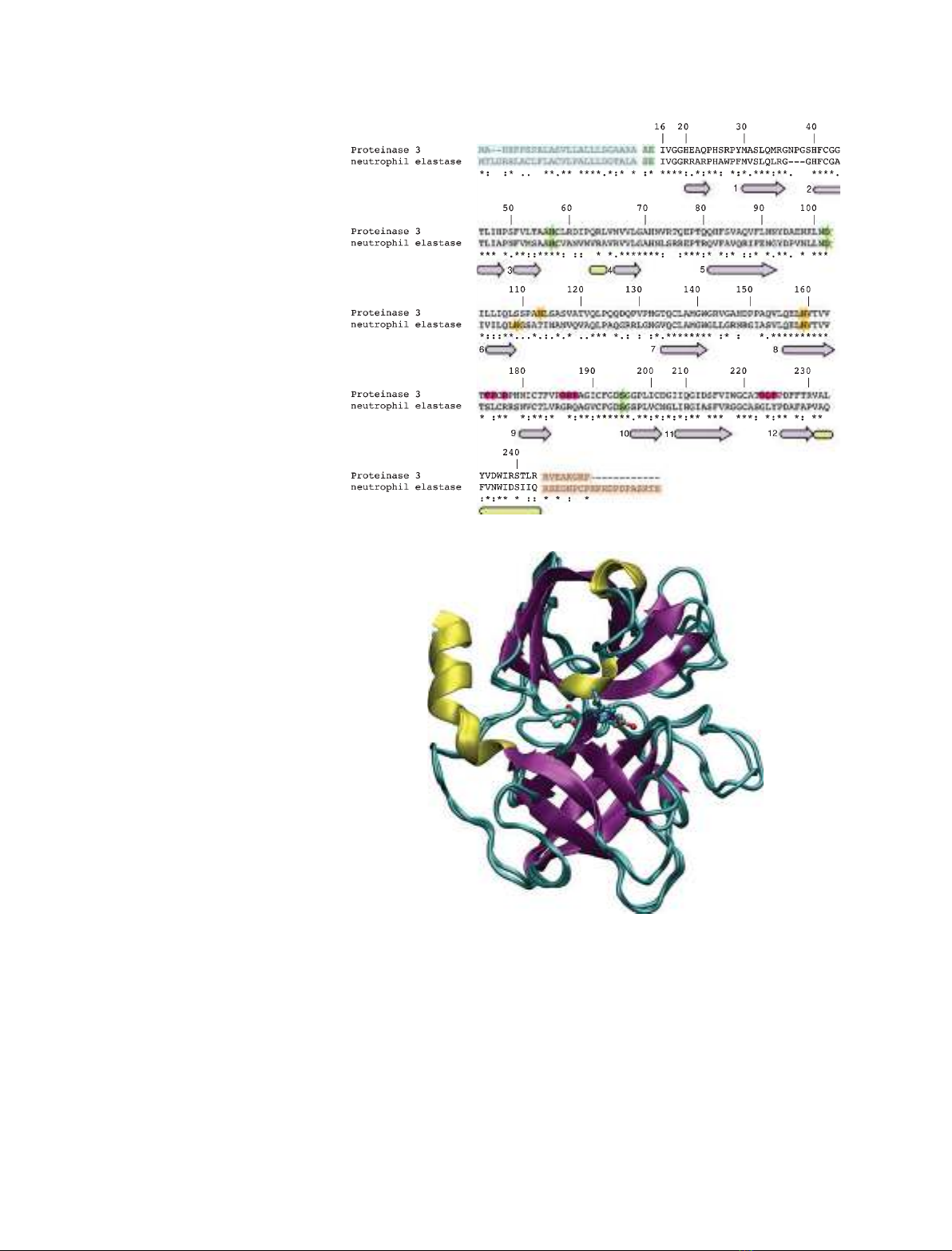

A

B

Fig. 3. Topology of hPr3 (A) and hNE (B).

Pink arrows, extended strands; yellow

cylinders, helices; green stars, catalytic

triad; orange stars, glycosylation sites; pink

circles, putative membrane binding site;

blue triangles, amino acids involved directly

in ligand binding. The extended strands

constituting the b-barrels are numbered 1–6

and 7–12 for the first and second barrels,

respectively.

Structure–function relationship of PR3 versus NE E. Hajjar et al.

2242 FEBS Journal 277 (2010) 2238–2254 ª2010 The Authors Journal compilation ª2010 FEBS

![Hình ảnh học bệnh não mạch máu nhỏ: Báo cáo [Năm]](https://cdn.tailieu.vn/images/document/thumbnail/2024/20240705/sanhobien01/135x160/1985290001.jpg)